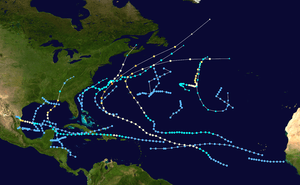

Tropical Depression Six (1975)

Tropical Depression Six caused significant flooding along the Gulf Coast of the United States, especially in the Florida Panhandle. The sixth tropical cyclone of the 1975 Atlantic hurricane season, the depression developed from a trough of low pressure in the northeastern Gulf of Mexico on July 28. The system strengthened slightly, but peaked with maximum sustained winds of 35 mph (55 km/h) – below tropical storm intensity. Early on July 29, the depression made landfall in eastern Louisiana. Once inland, the depression slowly weakened and re-curved northeastward on July 30 into Mississippi, shortly before degenerating into a remnant low pressure area. The remnants moved through northern Louisiana and Arkansas until dissipating on August 3.

| Tropical depression (SSHWS/NWS) | |

Surface weather analysis map on July 29 showing Tropical Depression Six, denoted by "LOW" | |

| Formed | July 28, 1975 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | August 1, 1975 |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 35 mph (55 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 1010 mbar (hPa); 29.83 inHg |

| Fatalities | 3 |

| Damage | $8.8 million (1975 USD) |

| Areas affected | Southern United States, Missouri, Illinois, and Indiana |

| Part of the 1975 Atlantic hurricane season | |

The tropical depression dropped heavy rainfall, with some areas of the Florida Panhandle experiencing more than 20 inches (510 mm) of precipitation. Rainfall from the depression contributed significantly toward making it the wettest July in the Florida Panhandle since 1923. Okaloosa, Santa Rosa, and Walton counties were hardest hit by flooding. Numerous roads were flooded and closed, with $3.2 million (1975 USD) in damage incurred to roadway infrastructure.[nb 1] About 500 homes suffered flood damage, 22 of which were destroyed. Damage is estimated to have reached $8.5 million in the state of Florida alone. Two deaths occurred in the state. In southern Alabama, overflowing rivers flooded several businesses and homes in Brewton and East Brewton. Damage in Alabama totaled approximately $300,000, while one fatality was reported. Heavy precipitation in Mississippi resulted in evacuations in the southern half of the state. Flood damage was reported in Canton, Moss Point, and Vicksburg, with water entering about a dozen homes in both Moss Point and Vicksburg.

Meteorological history

In late July, a trough of low pressure, which Hurricane Blanche avoided, was situated over the northeastern Gulf of Mexico.[1] The system developed into Tropical Depression Six at 12:00 UTC on July 28, while located about 60 mi (100 km) southwest of Cape San Blas, Florida.[2] The depression combined with a building high pressure system, resulting in the development of a strong convergence zone. This, in turn, caused heavy rainfall along the Gulf Coast, particularly in southern Alabama and the Florida Panhandle.[1] With sustained winds initially at 25 mph (35 km/h), the storm intensified slightly while tracking west-northwestward. Early on July 29, the depression attained its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 35 mph (55 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 1010 mbar (29.83 inHg). Several hours later, it made landfall in a rural area of St. Bernard Parish, Louisiana, with winds of 30 mph (45 km/h). The system curved northwestward and dissipated at 12:00 UTC on July 30, shortly after crossing into Mississippi.[2] The remnants continued into northern Louisiana and then turned northward, before dissipating over Arkansas on August 3.[3]

Impact

Florida

The depression dropped heavy rainfall to the north of its path, peaking at 20.84 in (529 mm) in DeFuniak Springs.[4] Precipitation from the depression contributed significantly to making the month of July one of the wettest on record in the Florida Panhandle. The region had its rainiest July since 1923, while Pensacola experienced its second wettest July, behind only 1940.[5] A number of rivers and creeks remained in excess of their banks for several days. To the west of the Apalachicola River, nearly all drainages experienced significant swelling.[6] Several homes in Pensacola Beach were flooded by the immense precipitation,[7] while the roof of a restaurant collapsed under the weight of water collecting on top of it.[5] On Santa Rosa Island, the sewage system overflowed into Pensacola Bay. A combination of above average tides and heavy rainfall caused the collapse of a 1,000 feet (300 m) section of sand along the Intracoastal Waterway, temporarily blocking barge traffic between Pensacola and Panama City.[7] In Pensacola, high water was reported at Naval Air Station.[5] Near Ensley, a tornado briefly touched down, damaging several mobile homes and knocking over some trees and power lines.[7] In Milton, the Blackwater River rose 1.5 ft (0.46 m) in a 3-hour period.[7] In Okaloosa County, the Shoal River, a tributary of Yellow River, crested around 15 ft (4.6 m), 1 ft (0.30 m) higher than the record height set in 1940. At Eglin Air Force Base, personnel and Vietnamese refugees repaired leaking tents and drilled holes in the plywood floors to drain the water.[8] In the Niceville–Valparaiso area, a number of streets were damaged, while the portions of the sewer system was put out of commission.[9]

In Walton County, several highways were closed due to high water, including the entire length of State Road 20 and a portion of State Road 2. A small fish pond dam burst in DeFuniak Springs, flooding some property but no buildings or homes.[10] Residents living near Alaqua Creek fled their homes after the creek went 6 to 8 ft (1.8 to 2.4 m) beyond its banks.[11] On July 31, the creek crested at 21.35 ft (6.51 m), approximately 3 ft (0.91 m) higher than any previous record height.[12] Flooding in Freeport forced at least 25 families to be rescued from their homes.[9] Choctawhatchee Bay, which was reportedly at its highest level in 20 years, overflowed above the bulkheads, flooding several buildings with up to 4 in (100 mm) of water.[7] Nearly all roads in northern Okaloosa and Walton counties were closed,[11] while several homes in low-lying areas of southern Okaloosa County were flooded after drains failed.[13] Further east, in Washington County, State Road 79 was closed at two locations due to water inundation.[10] At Deerpoint Lake in Bay County, the water rose as much as 7 ft (2.1 m) at some locations, flooding nearby lawns and homes.[14] In Wakulla County, 17 people evacuated as the Sopchoppy and Wakulla rivers rose.[15]

Throughout Florida, about 500 homes suffered flood damage, 22 of which were destroyed, with 188 businesses, homes, and trailers damaged in Okaloosa and Santa Rosa counties alone.[7] At least 60 families were left homeless.[16] The floodwaters swept away bridges, leaving three state roads impassible.[16] Two deaths were reported,[17] one of which occurred after a small boat capsized in St. Joseph Bay.[8] Flood damage in Bay, Gulf, Holmes, Okaloosa, Santa Rosa, Wakulla, and Walton counties reached about $8.5 million, including $3.2 million to roads and public works and $3 million to agriculture.[7]

Elsewhere

Flooding extended northward into Alabama. In Brewton, about 50 people were evacuated after Murder Creek began to swell. The creek crested at 16.7 ft (5.1 m) on August 1, about 3 ft (0.91 m) short of the record height set in April. Ten buildings and homes were flooded, while overall damage to public and private property reached an estimated $300,000. In East Brewton, several business were inundated with 3 to 4 ft (0.91 to 1.22 m) of water.[12] At Geneva, the Choctawhatchee River, normally ranging 4 to 5 ft (1.2 to 1.5 m) in height during that time of the year, reached 25.15 ft (7.67 m) by August 1 and rose at a rate of about 8 in (200 mm) per hour.[18] Residents of Geneva evacuated as the town began flooding, before returning to their homes by August 3 while some roads were still inundated, but the major highways were open to traffic.[19] One death occurred in the state after a 13-year-old boy fell into a drainage ditch near Mobile.[20]

In Mississippi, about 50 families in the vicinity of the Biloxi River were evacuated as the river threatened to exceed its banks, while at least 70 families fled their homes in Moss Point. Water entered about a dozen homes there. Further north, about 100 residences were evacuated in Canton, where some businesses suffered water damage. A total of 12 homes in Vicksburg were flooded.[21]

Aftermath

After surveying flooding from the depression in Florida, Governor Reubin Askew asked for a disaster declaration.[22] President of the United States Gerald Ford declared Bay, Gulf, Holmes, Okaloosa, Santa Rosa, Wakulla, Walton, and Washington counties a disaster area.[23] The declaration allowed low-interest loans to become available for repairs to small businesses and granted money to city and county governments to rebuild damaged buildings, bridges, and roads. Funds were also given to aid restoration of flooded farmland and damaged crops.[24]

See also

- List of Florida hurricanes (1975–99)

- Tropical Depression Ten (2007)

Notes

- All damage figures are in 1975 USD, unless otherwise noted

References

- Paul J. Hebert (April 1976). Atlantic Hurricane Season of 1975 (PDF). Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 464. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. May 25, 2020.

- David M. Roth (October 7, 2008). Tropical Depression Four – July 27–August 3, 1975. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (Report). Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- Roth, David M. (October 18, 2017). "Tropical Cyclone Point Maxima". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Data. United States Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- "Rainfall Heaviest Since '40". Pensacola News Journal. August 2, 1975. p. 11. Retrieved June 6, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- General Summary of National Flood Events. National Climatic Data Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. July 1975. p. 24. Retrieved November 5, 2016.

- "Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena" (PDF). Storm Data. Asheville, North Carolina: National Climatic Data Center. 17 (7): 18. July 1975. ISSN 0039-1972. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 5, 2016. Retrieved November 5, 2016.

- "Monsoon-Like Rains Hit Panhandle". Naples Daily News. Eglin Air Force Base, Florida. United Press International. August 1, 1975. p. 9. Retrieved February 19, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Worst Rain Over, But Wet Weekend Seen". Pensacola News Journal. August 2, 1975. p. 4. Retrieved June 6, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- Julian Webb (July 31, 1975). "Interior Counties Fortunate". The News Herald. p. 32. Retrieved February 19, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- Sheila Braxton (July 31, 1975). "Rain-Fed Creeks Force Evacuations". Northwest Florida Daily News. p. 1. Retrieved June 12, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- General Summary of National Flood Events. National Climatic Data Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. July 1975. p. 24. Retrieved November 5, 2016.

- Cathy Blum (August 1, 1975). "Disaster Area Status Asked for County". Northwest Florida Daily News. p. 1. Retrieved June 12, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Water Damage Viewed In Wake of Rainfall". The News Herald. August 1, 1975. p. 2. Retrieved February 18, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Water Damage Viewed In Wake of Rainfall". The News Herald. August 1, 1975. p. 1. Retrieved February 18, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "60 Florida Families Homeless in Flood". Albuquerque Journal. Milton, Florida. United Press International. August 4, 1975. p. 16. Retrieved February 18, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Major Disaster Declared". The Palm Beach Post. Tallahassee, Florida. United Press International. August 23, 1975. p. 25. Retrieved March 17, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- Bill Prime (August 2, 1975). "Geneva Evacuates Threatened Areas". Pensacola News Journal. Geneva, Alabama. p. 3. Retrieved June 6, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- Michael McIntyre (August 4, 1975). "Flood Evacuees Return". Pensacola News Journal. p. 1. Retrieved June 6, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Rains create problems for Vietnam refugees". The Mercury. United Press International. August 1, 1975. p. 3. Retrieved April 12, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Mid-Delta". Delta Democrat Times. August 3, 1975. p. 38. Retrieved April 9, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- Don Bates and Bill Purvis (August 7, 1975). "Askew Acts to Aid 8 Counties". Pensacola News Journal. p. 1. Retrieved June 12, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- United States Department of Homeland Security. "Florida Flooding (DR-479)". Federal Emergency Management Agency. Retrieved October 31, 2012.

- Bill Purvis (August 14, 1975). "Askew Asks West Florida Flood Disaster Funds". Pensacola News Journal. p. 3. Retrieved June 12, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.