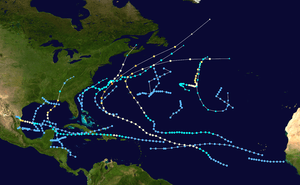

Hurricane Gladys (1975)

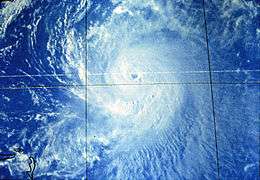

Hurricane Gladys was the farthest tropical cyclone from the United States to be observed by radar in the Atlantic basin since Hurricane Carla in 1961.[1] The seventh named storm and fifth hurricane of the 1975 Atlantic hurricane season, Gladys developed from a tropical wave while several hundred miles southwest of Cape Verde on September 22. Initially, the tropical depression failed to strengthen significantly, but due to warm sea surface temperatures and low wind shear, it became Tropical Storm Gladys by September 24. Despite entering a more unfavorable environment several hundred miles east of the northern Leeward Islands, Gladys became a Category 1 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale on September 28. Shortly thereafter, the storm reentered an area favorable for strengthening. Eventually, a well-defined eye became visible on satellite imagery.

| Category 4 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

Gladys as a Category 3 hurricane | |

| Formed | September 22, 1975 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | October 4, 1975 |

| (Extratropical after October 3) | |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 140 mph (220 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 939 mbar (hPa); 27.73 inHg |

| Fatalities | None reported |

| Areas affected | Eastern United States, Newfoundland and Labrador |

| Part of the 1975 Atlantic hurricane season | |

As the storm tracked to the east of the Bahamas, a curve to the north began, at which time an anticyclone developed atop the cyclone. This subsequently allowed Gladys to rapidly intensify into a Category 4 hurricane, reaching maximum sustained winds of 140 mph (230 km/h) on October 2. Thereafter, Gladys began to weaken and passed very close to Cape Race, Newfoundland before merging with a large extratropical cyclone the next day. Effects from the system along the East Coast of the United States were minimal, although heavy rainfall and rough seas were reported. In Newfoundland, strong winds and light precipitation were observed.

Meteorological history

On September 17, a tropical wave emerged into the Atlantic Ocean off the western coast of Africa. The disturbance followed another tropical wave which became Hurricane Faye several days later, before turning west near the 11th parallel. Based on estimates from the Dvorak Technique, the wave was designated a tropical depression at 18:00 UTC on September 22. Due to favorable conditions such as low wind shear and warm sea surface temperatures, the depression strengthened into a tropical storm and was named Gladys by the National Hurricane Center (NHC) on September 24.[2] After becoming a tropical storm, Gladys slowly intensified as winds increased to 50 mph (80 km/h). The storm then moved west-northwest, and on September 25, Gladys strengthened into a Category 1 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale (SSHWS).[3] Despite strong wind shear,[2] the storm maintained minimal hurricane status.[3] However, early on September 28, the barometric pressure increased to 1,000 mb (30 inHg); the NHC notes that Gladys may have briefly weakened into a tropical storm at this time.[2]

After passing through the trough that generated the wind shear, the storm began to strengthen again.[2] While moving about 350 miles (560 km) north of Puerto Rico on September 30, the winds of the storm increased to 90 mph (145 km/h).[3] By this time, an eye was clearly visible on satellite imagery. After holding steady for 36 hours, the storm recurved around a ridge on October 1. Gladys then began to undergo rapid deepening,[2] becoming a Category 2 hurricane at 18:00 UTC and Category 3 hurricane the following day. Early on October 2, the storm strengthened into a Category 4 hurricane.[3] At 08:46 UTC on October 2, Hurricane Hunters measured maximum sustained winds of 140 mph (225 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 939 mbar (27.7 inHg).[2] Moving northeast,[3] the hurricane hunters soon observed a pressure of 940 mbar (28 inHg), making it the one of the most intense high-latitude storms ever observed. Despite its distance from Cape Hatteras, the system was briefly observed on radar. It became one of few hurricanes at the time to be seen on radar over 150 mi (240 km) from the continental United States.[2] Thereafter, the storm weakened slightly, and was downgraded to a Category 3 hurricane early on October 3.[3] Accelerating at unusually high speeds, Gladys passed 70 miles (115 km) southeast of Cape Race, Newfoundland on October 3. The storm finally merged with a large extratropical cyclone on October 4.[2]

Observation, preparations and impact

While over the Atlantic Ocean, a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) C-130 hurricane hunter aircraft flew into Gladys on October 1 on a research mission. The mission was to study the storm and use the information to improve seeding operations for the now-defunct Project Stormfury.[4][5]

Gladys was the strongest storm to threaten the East Coast of the United States since Hurricane Hazel in 1954.[2] Although initially not expected to threaten,[6] meteorologists at the NHC forecast the storm to make landfall along the East Coast of the United States within three days.[7] A hurricane watch was issued for North Carolina's Outer Banks on October 1,[8] extending from Cape Lookout to Kitty Hawk.[2] However, the watch discontinued as Gladys pulled away,[9] though the storm was still considered a threat to the nation.[10] In Manteo, residents began laying sandbags and filling their cars up with fuel in anticipation for possible evacuation, and the United States Coast Guard sent a plane equipped with a loudspeaker to warn fishermen of the hurricane.[11] However, despite warnings, about 40 fishermen went to Cape Point near Cape Hatteras due to the "increased feeding activities" of fish during rough seas.[12] All small crafts were advised to stay out of the water.[13] Elsewhere in the Outer Banks, residents evacuated to hotels in Elizabeth City and four United States Coast Guard servicemen stationed at a lighthouse in Cape Hatteras were evacuated.[14]

While passing the Outer Banks, a campground and road was closed due to 8 ft (2 m) waves. As the cyclone moved northward. In all, the effects of the storm on North Carolina were minimal.[2] While tracking rapidly to the southeast of Newfoundland, light rainfall was observed, including 1.46 in (37 mm) of precipitation in St. John's.[15] Strong winds were also reported on the island.[2]

See also

- List of Category 4 Atlantic hurricanes

- Other storms of the same name

References

- Michael G. Carelli (1976). "Picture of the Month:Cape Hatteras Radar Observations of Hurricane Gladys". American Meteorological Society. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Paul J. Herbert (April 1976). Atlantic Hurricane Season of 1975 (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Retrieved May 18, 2014.

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. May 25, 2020.

- "Scientists Call Gladys a Classic Hurricane". Naples Daily News. United Press International. 1975.

- A. B. C. Whipple (1982). Storm. Time Life. ISBN 0-8094-4312-0.

- "Hurricane picks up strength". Lewiston-News Journal. Miami, Florida. Associated Press. September 30, 1975. Retrieved August 2, 2013.

- "Hurricane Gladys On Possible US Mainland Course". The Robesonian. Associated Press. September 30, 1975.

- "Hurricane Watch for Carolina". Daytona Beach Morning-Journal. Miami, Florida. Associated Press. October 2, 1975. Retrieved August 2, 2013.

- "Two Weather System's Dominate NC's Forecast". The Times-News. Associated Press. October 1, 1975. Retrieved August 2, 2013.

- ""Gladys" Still Seen as Threat". Bangor Daily News. Miami, Florida. United Press International. October 2, 1975. Retrieved August 2, 2013.

- "Gladys Turns Seaward". Ruston Daily Leader. United Press International. 1975.

- Don Lohwasser (October 2, 1975). "Gladys turns from North Carolina coast". The Bryan Times. Manteo, North Carolina. United Press International. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- "Gladys is flirting with Newfounland". Record-Journal. Miami, Florida. Associated Press. October 3, 1975. Retrieved August 2, 2013.

- "Gladys Missing". The Bee. Associated Press. 1975.

- 1975-Gladys (Report). Moncton, New Brunswick: Environment Canada. November 4, 2009. Retrieved June 3, 2014.