Tourette syndrome

Tourette syndrome or Tourette's syndrome (abbreviated as TS or Tourette's) is a common neurodevelopmental disorder that begins in childhood or adolescence. It is characterized by multiple movement (motor) tics and at least one vocal (phonic) tic. Common tics are blinking, coughing, throat clearing, sniffing, and facial movements. These are typically preceded by an unwanted urge or sensation in the affected muscles, can sometimes be suppressed temporarily, and characteristically change in location, strength, and frequency. Tourette's is at the more severe end of a spectrum of tic disorders. The tics often go unnoticed by casual observers.

| Tourette syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Tourette's syndrome, Tourette's disorder, Gilles de la Tourette syndrome (GTS), combined vocal and multiple motor tic disorder [de la Tourette] |

| |

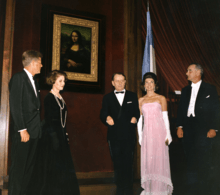

| Georges Gilles de la Tourette (1857–1904), namesake of Tourette syndrome | |

| Specialty | Pediatrics, neurology |

| Symptoms | Tics[1] |

| Usual onset | Typically in childhood[1] |

| Duration | Long term[2] |

| Causes | Genetic with environmental influence[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on history and symptoms[1] |

| Medication | Usually none, occasionally neuroleptics and noradrenergics[1] |

| Prognosis | Improvement to disappearance of tics beginning in late teens[2] |

| Frequency | About 1%[3] |

Tourette's was once regarded as a rare and bizarre syndrome and has popularly been associated with coprolalia (the utterance of obscene words or socially inappropriate and derogatory remarks). It is no longer considered rare; about 1% of school-age children and adolescents are estimated to have Tourette's,[1] and coprolalia occurs only in a minority. There are no specific tests for diagnosing Tourette's; it is not always correctly identified, because most cases are mild, and the severity of tics decreases for most children as they pass through adolescence. Therefore, many go undiagnosed or may never seek medical attention. Extreme Tourette's in adulthood, though sensationalized in the media, is rare, but for a small minority, severely debilitating tics can persist into adulthood. Tourette's does not affect intelligence or life expectancy.

There is no cure for Tourette's and no single most effective medication. In most cases, medication for tics is not necessary, and behavioral therapies are the first-line treatment. Education is an important part of any treatment plan, and explanation alone often provides sufficient reassurance that no other treatment is necessary.[1] Among those who are referred to specialty clinics, other conditions like attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) are more likely than in the broader population of persons with Tourette's. These co-occurring diagnoses often cause more impairment to the individual than the tics; hence it is important to correctly distinguish co-occurring conditions and treat them.

Tourette syndrome was named by French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot for his intern, Georges Gilles de la Tourette, who published in 1885 an account of nine patients with a "convulsive tic disorder". While the exact cause is unknown, it is believed to involve a combination of genetic and environmental factors. The mechanism appears to involve dysfunction in neural circuits between the basal ganglia and related structures in the brain.

Classification

Tourette syndrome is classified as a motor disorder (a disorder of the nervous system that causes abnormal and involuntary movements). It is listed in the neurodevelopmental disorder category of the fifth version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), published in 2013.[4] Tourette's is at the more severe end of the spectrum of tic disorders; its diagnosis requires multiple motor tics and at least one vocal tic to be present for more than a year. Tics are sudden, repetitive, nonrhythmic movements that involve discrete muscle groups,[5] while vocal (phonic) tics involve laryngeal, pharyngeal, oral, nasal or respiratory muscles to produce sounds.[6][7] The tics must not be explained by other medical conditions or substance use.[8]

Other conditions on the spectrum include persistent (chronic) motor or vocal tics, in which one type of tic (motor or vocal, but not both) has been present for more than a year; and provisional tic disorder, in which motor or vocal tics have been present for less than one year.[9][10] The fifth edition of the DSM replaced what had been called transient tic disorder with provisional tic disorder, recognizing that "transient" can only be defined in retrospect.[11][12][13] Some experts believe that TS and persistent (chronic) motor or vocal tic disorder should be considered the same condition, because vocal tics are also motor tics in the sense that they are muscular contractions of nasal or respiratory muscles.[14][10]

Tic disorders are defined only slightly differently by the World Health Organization (WHO);[3] in its ICD-10, the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, TS is described as "combined vocal and multiple motor tic disorder [de la Tourette]", code F95.2 in chapter V, mental and behavioural disorders,[15] equivalent to 307.23 in DSM-5, Tourette's disorder.[4] Most published research on TS originates in the United States, and in international research the DSM is preferred over the WHO classification.[11]

Genetic studies indicate that tic disorders cover a spectrum that is not recognized by the clear-cut distinctions in the current diagnostic framework.[8] Studies have suggested since 2008 that Tourette's is not a unitary condition with a distinct mechanism as described in the existing classification systems; the studies suggest instead that subtypes should be recognized to distinguish "pure TS" from TS that is accompanied by attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) or other disorders.[3][8][9] Elucidation of these subtypes awaits fuller understanding of the genetic and other causes of tic disorders (similar to the subtypes established for other conditions, for example, in distinguishing type 1 and type 2 diabetes).[11]

Characteristics

Tics

Tics are movements or sounds that take place "intermittently and unpredictably out of a background of normal motor activity",[16] having the appearance of "normal behaviors gone wrong".[17] The tics associated with Tourette's wax and wane; they change in number, frequency, severity and anatomical location, and each person experiences a unique pattern of fluctuation in their severity and frequency. Tics may also occur in "bouts of bouts", which also vary among people.[18] The variation in tic severity may occur over hours, days, or weeks.[9] Tics may increase when someone is experiencing stress, fatigue, anxiety, or illness,[8][19] or when engaged in relaxing activities like watching TV. They sometimes decrease when an individual is engrossed in or focused on an activity like playing a musical instrument.[8][20]

In contrast to the abnormal movements associated with other movement disorders such as choreas, dystonias, myoclonus, and dyskinesias, the tics of Tourette's are nonrhythmic, temporarily suppressible, and often preceded by an unwanted urge.[18][21] The ability to suppress tics varies among individuals, and may be more developed in adults than children.[22] People with tics are sometimes able to suppress them for limited periods of time, but doing so often results in tension or mental exhaustion.[1][23] People with Tourette's may seek a secluded spot to release the suppressed urge, or there may be a marked increase in tics after a period of suppression at school or work.[9][17] Children may suppress tics while in the doctor's office, so they may need to be observed when not aware of being watched.[24]

Over time, about 90% of individuals with Tourette's feel an urge preceding the tic,[9] similar to the urge to sneeze or scratch an itch. The urges and sensations that precede the expression of a tic are referred to as premonitory sensory phenomena or premonitory urges. These urges may be physical or mental.[25] People describe the urge to express the tic as a buildup of tension, pressure, or energy[26][27] which they ultimately choose consciously to release, as if they "had to do it"[28] to relieve the sensation[26] or until it feels "just right".[28][29] Examples of this urge are the feeling of having something in one's throat, or a localized discomfort in the shoulders, which lead to the need to clear one's throat or shrug the shoulders. The actual tic may be felt as relieving this tension or sensation, similar to scratching an itch or blinking to relieve an uncomfortable feeling in the eye. Because of the urges that precede them, tics are described as semi-voluntary or "unvoluntary",[1][16] rather than specifically involuntary; they may be experienced as a voluntary, suppressible response to the unwanted premonitory urge.[18][20] Some people with Tourette's may not be aware of the premonitory urge associated with tics. Children may be less aware of it than are adults,[9] but their awareness tends to increase with maturity;[16] by the age of ten, most children recognize the premonitory urge.[20]

Complex tics related to speech include coprolalia, echolalia and palilalia. Coprolalia is the spontaneous utterance of socially objectionable or taboo words or phrases. Although it is the most publicized symptom of Tourette's, only about 10% of people with Tourette's exhibit it, and it is not required for a diagnosis.[1][30] Echolalia (repeating the words of others) and palilalia (repeating one's own words) occur in a minority of cases.[31] Complex motor tics include copropraxia (obscene or forbidden gestures, or inappropriate touching), echopraxia (repetition or imitation of another person's actions) and palipraxia (repeating one's own movements).[22]

Onset and progression

There is no typical case of Tourette syndrome,[32] but the age of onset and the severity of symptoms follow a fairly reliable course. Although onset may occur anytime before eighteen years, the typical age of onset of tics is from five to seven, and is usually before adolescence.[1] A 1998 study from the Yale Child Study Center showed that tic severity increased with age until it reached its highest point between ages eight and twelve.[33] Severity declines steadily for most children as they pass through adolescence, when half to two-thirds of children see a dramatic decrease in tics.[34]

The first tics to appear usually affect the head, face, and shoulders, and include blinking, facial movements, sniffing and throat clearing.[9] Vocal tics often appear months or years after motor tics but can appear first.[10][11] Among people who experience more severe tics, complex tics may develop, including "arm straightening, touching, tapping, jumping, hopping and twirling".[9] There are different movements in contrasting disorders (for example, the autism spectrum disorders), such as self-stimulation and stereotypies. These stereotyped movements typically have an earlier age of onset; are more symmetrical, rhythmical and bilateral; and involve the extremities (for example, flapping the hands).[35]

The severity of symptoms varies widely among people with Tourette's, and many cases may be undetected.[1][3][10][31] Most cases are mild and almost unnoticeable;[36][37] many people with TS may not realize they have tics. Because tics are more commonly expressed in private, Tourette syndrome may go unrecognized,[38] and casual observers might not notice tics.[30][39][40]

Most adults have mild TS and do not seek medical attention.[1] While tics subside for the majority after adolescence, some of the "most severe and debilitating forms of tic disorder are encountered" in adults.[41] In some cases, what appear to be adult-onset tics can be childhood tics re-surfacing.[41]

Co-occurring conditions

Because people with milder symptoms are unlikely to be referred to specialty clinics, studies of Tourette's have an inherent bias towards more severe cases.[45] When symptoms are severe enough to warrant referral to clinics, ADHD and OCD are often also found.[1] In specialty clinics, 30% of those with TS also have mood or anxiety disorders or disruptive behaviors.[9][46] In the absence of ADHD, tic disorders do not appear to be associated with disruptive behavior or functional impairment,[47] while impairment in school, family, or peer relations is greater in those who have more comorbid conditions.[17][48] When ADHD is present along with tics, the occurrence of conduct disorder and oppositional defiant disorder increases.[9] Aggressive behaviors and angry outbursts in people with TS are not well understood; they are not associated with severe tics, but are connected with the presence of ADHD.[49] ADHD may also contribute to higher rates of anxiety, and aggression and anger control problems are more likely when both OCD and ADHD co-occur with Tourette's.[41]

Compulsions that resemble tics are present in some individuals with OCD; "tic-related OCD" is hypothesized to be a subgroup of OCD, distinguished from non-tic related OCD by the type and nature of obsessions and compulsions.[50] Compared to the more typical compulsions of OCD without tics that relate to contamination, tic-related OCD presents with more "counting, aggressive thoughts, symmetry and touching" compulsions.[9] Compulsions associated with OCD without tics are usually related to obsessions and anxiety, while those in tic-related OCD are more likely to be a response to a premonitory urge.[9] There are increased rates of anxiety and depression in those adults with TS who also have OCD.[41]

Among individuals with TS studied in clinics, between 2.9% and 20% had autism spectrum disorders,[51] but one study indicates that a high association of autism and TS may be partly due to difficulties distinguishing between tics and tic-like behaviors or OCD symptoms seen in people with autism.[52]

Not all people with Tourette's have ADHD or OCD or other comorbid conditions, and estimates of the rate of pure TS or TS-only vary from 15% to 57%;[lower-alpha 1] in clinical populations, a high percentage of those under care do have ADHD.[29][53] Children and adolescents with pure TS are not significantly different from their peers without TS on ratings of aggressive behaviors or conduct disorders, or on measures of social adaptation.[3] Similarly, adults with pure TS do not appear to have the social difficulties present in those with TS plus ADHD.[3]

Among those with an older age of onset, more substance abuse and mood disorders are found, and there may be self-injurious tics. Adults who have severe, often treatment-resistant tics are more likely to also have mood disorders and OCD.[41] Coprolalia is more likely in people with severe tics plus multiple comorbid conditions.[22]

Neuropsychological function

There are no major impairments in neuropsychological function among people with Tourette's, but conditions that occur along with tics can cause variation in neurocognitive function. A better understanding of comorbid conditions is needed to untangle any neuropsychological differences between TS-only individuals and those with comorbid conditions.[48]

Only slight impairments are found in intellectual ability, attentional ability, and nonverbal memory—but ADHD, other comorbid disorders, or tic severity could account for these differences. In contrast with earlier findings, visual motor integration and visuoconstructive skills are not found to be impaired, while comorbid conditions may have a small effect on motor skills. Comorbid conditions and severity of tics may account for variable results in verbal fluency, which can be slightly impaired. There might be slight impairment in social cognition, but not in the ability to plan or make decisions.[48] Children with TS-only do not show cognitive deficits. They are faster than average for their age on timed tests of motor coordination, and constant tic suppression may lead to an advantage in switching between tasks because of increased inhibitory control.[3][55]

Learning disabilities may be present, but whether they are due to tics or comorbid conditions is controversial; older studies that reported higher rates of learning disability did not control well for the presence of comorbid conditions.[56] There are often difficulties with handwriting, and disabilities in written expression and math are reported in those with TS plus other conditions.[56]

Causes

The exact cause of Tourette's is unknown, but it is well established that both genetic and environmental factors are involved.[8][9][57] Genetic epidemiology studies have shown that Tourette's is highly heritable,[58] and 10 to 100 times more likely to be found among close family members than in the general population.[59] The exact mode of inheritance is not known; no single gene has been identified, and hundreds of genes are likely involved.[58][59][60] Genome-wide association studies were published in 2013[1] and 2015[9] in which no finding reached a threshold for significance.[1] Twin studies show that 50 to 77% of identical twins share a TS diagnosis, while only 10 to 23% of fraternal twins do.[8] But not everyone who inherits the genetic vulnerability will show symptoms.[61][62] A few rare highly penetrant genetic mutations have been found that explain only a small number of cases in single families (the SLITRK1, HDC, and CNTNAP2 genes).[63]

Psychosocial or other non-genetic factors—while not causing Tourette's—can affect the severity of TS in vulnerable individuals and influence the expression of the inherited genes.[3][32][57][59] Pre-natal and peri-natal events increase the risk that a tic disorder or comorbid OCD will be expressed in those with the genetic vulnerability. These include paternal age; forceps delivery; stress or severe nausea during pregnancy; and use of tobacco, caffeine, alcohol,[3] and cannabis during pregnancy.[1] Babies who are born premature with low birthweight, or who have low Apgar scores, are also at increased risk; in premature twins, the lower birthweight twin is more likely to develop TS.[3]

Autoimmune processes may affect the onset of tics or exacerbate them. Both OCD and tic disorders may arise in a subset of children as a result of a post-streptococcal autoimmune process.[36] Its potential effect is described by the controversial hypothesis called PANDAS (pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections), which proposes five criteria for diagnosis in children.[64][65] PANDAS and the newer PANS (pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome) hypotheses are the focus of clinical and laboratory research, but remain unproven. There is also a broader hypothesis that links immune-system abnormalities and immune dysregulation with TS.[9][36]

Some forms of OCD may be genetically linked to Tourette's,[29] although the genetic factors in OCD with and without tics may differ.[8] The genetic relationship of ADHD to Tourette syndrome, however, has not been fully established.[55][66][46] A genetic link between autism and Tourette's has not been established as of 2017.[41]

Mechanism

.svg.png)

The exact mechanism affecting the inherited vulnerability to Tourette's is not well established.[8] Tics are believed to result from dysfunction in cortical and subcortical brain regions: the thalamus, basal ganglia and frontal cortex.[67] Neuroanatomic models suggest failures in circuits connecting the brain's cortex and subcortex;[32] imaging techniques implicate the frontal cortex and basal ganglia.[60] In the 2010s, neuroimaging and postmortem brain studies, as well as animal and genetic studies,[48][68] made progress towards better understanding the neurobiological mechanisms leading to Tourette's.[48] These studies support the basal ganglia model, in which neurons in the striatum are activated and inhibit outputs from the basal ganglia.[49]

Cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical (CSTC) circuits, or neural pathways, provide inputs to the basal ganglia from the cortex. These circuits connect the basal ganglia with other areas of the brain to transfer information that regulates planning and control of movements, behavior, decision-making, and learning.[48] Behavior is regulated by cross-connections that "allow the integration of information" from these circuits.[48] Involuntary movements may result from impairments in these CSTC circuits,[48] including the sensorimotor, limbic, language and decision making pathways. Abnormalities in these circuits may be responsible for tics and premonitory urges.[69]

The caudate nuclei may be smaller in subjects with tics compared to those without tics, supporting the hypothesis of pathology in CSTC circuits in Tourette's.[48] The ability to suppress tics depends on brain circuits that "regulate response inhibition and cognitive control of motor behavior".[68] Children with TS are found to have a larger prefrontal cortex, which may be the result of an adaptation to help regulate tics.[68] It is likely that tics decrease with age as the capacity of the frontal cortex increases.[68] Cortico-basal ganglia (CBG) circuits may also be impaired, contributing to "sensory, limbic and executive" features.[9] The release of dopamine in the basal ganglia is higher in people with Tourette's, implicating biochemical changes from "overactive and dysregulated dopaminergic transmissions".[57]

Histamine and the H3 receptor may play a role in the alterations of neural circuitry.[9][70][71][72] A reduced level of histamine in the H3 receptor may result in an increase in other neurotransmitters, causing tics.[73] Postmortem studies have also implicated "dysregulation of neuroinflammatory processes".[8]

Diagnosis

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), Tourette's may be diagnosed when a person exhibits both multiple motor tics and one or more vocal tics over a period of one year. The motor and vocal tics need not be concurrent. The onset must have occurred before the age of 18 and cannot be attributed to the effects of another condition or substance (such as cocaine).[4] Hence, other medical conditions that include tics or tic-like movements—for example, autism or other causes of tics—must be ruled out.[74]

There are no specific medical or screening tests that can be used to diagnose Tourette's;[29] the diagnosis is usually made based on observation of the individual's symptoms and family history,[30] and after ruling out secondary causes of tic disorders.[75] Tics that may appear to mimic those of Tourette's—but are associated with disorders other than Tourette's—are known as tourettism.[76] Most of these conditions, including dystonias, choreas, and other genetic conditions, are rarer than tic disorders and a thorough history and examination may be enough to rule them out without medical or screening tests.[1][32][76]

Delayed diagnosis often occurs because professionals mistakenly believe that TS is rare, always involves coprolalia, or must be severely impairing.[77] The DSM has recognized since 2000 that many individuals with Tourette's do not have significant impairment;[11][74][78] diagnosis does not require the presence of coprolalia or a comorbid condition, such as ADHD or OCD.[30][77] Tourette's may be misdiagnosed because of the wide expression of severity, ranging from mild (in the majority of cases) or moderate, to severe (the rare but more widely recognized and publicized cases).[33] About 20% of people with Tourette syndrome do not realize that they have tics.[32] Tics that appear early in the course of TS are often confused with allergies, asthma, vision problems, and other conditions. Pediatricians, allergists and ophthalmologists are among the first to identify a child as having tics,[31] although the majority of tics are first identified by the child's parents.[77] Coughing, blinking, and tics that mimic unrelated conditions such as asthma are commonly misdiagnosed.[30] In the UK, there is an average delay of three years between symptom onset and diagnosis.[3]

Assessment and screening for other conditions

- Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS), recommended in international guidelines to assess "frequency, intensity, complexity, distribution, interference and impairment" of or due to tics

- Tourette Syndrome Clinical Global Impression (TS–CGI) and Shapiro TS Severity Scale (STSS), for a briefer assessment of tics than YGTSS

- Tourette's Disorder Scale (TODS), to assess tics and comorbidities

- Premonitory Urge for Tics Scale (PUTS), for individuals over age ten

- Motor tic, Obsessions and compulsions, Vocal tic Evaluation Survey (MOVES), to evaluate complex tics and other behaviors

- Autism—Tics, AD/HD, and other Comorbities (A–TAC), to screen for other conditions

Patients referred for a tic disorder are assessed based on their family history of tics, vulnerability to ADHD, obsessive–compulsive symptoms, and a number of other chronic medical, psychiatric and neurological conditions.[81][82] In individuals with a typical onset and a family history of tics or OCD, a basic physical and neurological examination may be sufficient.[83] If another condition might better explain the tics, tests may be done; for example, if there is diagnostic confusion between tics and seizure activity, an EEG may be ordered. An MRI can rule out brain abnormalities,[81] but such brain imaging studies are not usually warranted.[81] Measuring thyroid-stimulating hormone blood levels can rule out hypothyroidism, which can be a cause of tics. In teenagers and adults presenting with a sudden onset of tics and other behavioral symptoms, a urine drug screen for cocaine and stimulants might be necessary. If there is a family history of liver disease, serum copper and ceruloplasmin levels can rule out Wilson's disease.[83]

Although not all those with Tourette's have comorbid conditions, most presenting for clinical care exhibit symptoms of other conditions along with their tics.[55] ADHD and OCD are the most common, but autism spectrum disorders or anxiety, mood, personality, oppositional defiant, and conduct disorders may also be present.[6] Learning disabilities and sleep disorders may be present;[30] higher rates of sleep disturbance and migraine than in the general population are reported.[84] A thorough evaluation for comorbidity is called for when symptoms and impairment warrant,[82][83] and careful assessment of people with TS includes comprehensive screening for these conditions.[6][59]

Comorbid conditions such as OCD and ADHD can be more impairing than tics, and cause greater impact on overall functioning.[14][32] Disruptive behaviors, impaired functioning, or cognitive impairment in individuals with comorbid Tourette's and ADHD may be accounted for by the ADHD, highlighting the importance of identifying comorbid conditions.[9][29][30][85] Children and adolescents with TS who have learning difficulties are candidates for psychoeducational testing, particularly if the child also has ADHD.[81][82]

Management

There is no cure for Tourette's.[86] There is no single most effective medication,[1] and no one medication effectively treats all symptoms. Most medications prescribed for tics have not been approved for that use, and no medication is without the risk of significant adverse effects.[14][30][87] Treatment is focused on identifying the most troubling or impairing symptoms and helping the individual manage them.[30] Because comorbid conditions are often a larger source of impairment than tics,[81] they are a priority in treatment.[88] The management of Tourette's is individualized and involves shared decision-making between the clinician, patient, family and caregivers.[88][89] Practice guidelines for the treatment of tics were published by the American Academy of Neurology in 2019.[88]

Education, reassurance and psychobehavioral therapy are often sufficient for the majority of cases.[1][30][90] In particular, psychoeducation targeting the patient and their family and surrounding community is a key management strategy.[91][92] Watchful waiting "is an acceptable approach" for those who are not functionally impaired.[88] Symptom management may include behavioral, psychological and pharmacological therapies. Pharmacological intervention is reserved for more severe symptoms, while psychotherapy or cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) may ameliorate depression and social isolation, and improve family support.[30] The decision to use behavioral or pharmacological treatment is "usually made after the educational and supportive interventions have been in place for a period of months, and it is clear that the tic symptoms are persistently severe and are themselves a source of impairment in terms of self-esteem, relationships with the family or peers, or school performance".[80]

Psychoeducation and social support

Knowledge, education and understanding are uppermost in management plans for tic disorders,[30] and psychoeducation is the first step.[93] A child's parents are typically the first to notice their tics;[77] they may feel worried, imagine that they are somehow responsible, or feel burdened by misinformation about Tourette's.[93] Effectively educating parents about the diagnosis and providing social support can ease their anxiety. This support can also lower the chance that their child will be unnecessarily medicated[94] or experience an exacerbation of tics due to their parents' emotional state.[6]

People with Tourette's may suffer socially if their tics are viewed as "bizarre". If a child has disabling tics, or tics that interfere with social or academic functioning, supportive psychotherapy or school accommodations can be helpful.[75] Even children with milder tics may be angry, depressed or have low self-esteem as a result of increased teasing, bullying, rejection by peers or social stigmatization, and this can lead to social withdrawal. Some children feel empowered by presenting a peer awareness program to their classmates.[59][89][95] It can be helpful to educate teachers and school staff about typical tics, how they fluctuate during the day, how they impact the child, and how to distinguish tics from naughty behavior. By learning to identify tics, adults can refrain from asking or expecting a child to stop ticcing,[23][95] because "tic suppression can be exhausting, unpleasant, and attention-demanding and can result in a subsequent rebound bout of tics".[23]

Adults with TS may withdraw socially to avoid stigmatization and discrimination because of their tics.[96] Depending on their country's healthcare system, they may receive social services or help from support groups.[97]

Behavioral

Behavioral therapies using habit reversal training (HRT) and exposure and response prevention (ERP) are first-line interventions in the management of Tourette syndrome,[98] and have been shown to be effective.[8] Because tics are somewhat suppressible, when people with TS are aware of the premonitory urge that precedes a tic, they can be trained to develop a response to the urge that competes with the tic.[9][98] Comprehensive behavioral intervention for tics (CBIT) is based on HRT, the best researched behavioral therapy for tics.[98] TS experts debate whether increasing a child's awareness of tics with HRT/CBIT (as opposed to ignoring tics) can lead to more tics later in life.[98]

When disruptive behaviors related to comorbid conditions exist, anger control training and parent management training can be effective.[3][99][100] CBT is a useful treatment when OCD is present.[9] Relaxation techniques, such as exercise, yoga and meditation may be useful in relieving the stress that can aggravate tics. Beyond HRT, the majority of behavioral interventions for Tourette's (for example, relaxation training and biofeedback) have not been systematically evaluated and are not empirically supported.[101]

Medication

Children with tics typically present when their tics are most severe, but because the condition waxes and wanes, medication is not started immediately or changed often.[32] Tics may subside with education, reassurance and a supportive environment.[1][59] When medication is used, the goal is not to eliminate symptoms. Instead, the lowest dose that manages symptoms without adverse effects is used, because adverse effects may be more disturbing than the symptoms being treated with medication.[32]

The classes of medication with proven efficacy in treating tics—typical and atypical neuroleptics—can have long-term and short-term adverse effects.[59] Some antihypertensive agents are also used to treat tics; studies show variable efficacy but a lower side effect profile than the neuroleptics.[8][102] The antihypertensives clonidine and guanfacine are typically tried first in children; they can also help with ADHD symptoms,[59][102] but there is less evidence that they are effective for adults.[1] The neuroleptics risperidone and aripiprazole are tried when antihypertensives are not effective,[14][59] and are generally tried first for adults.[1] The most effective medication for tics is haloperidol, but it has a higher risk of side effects.[59] Methylphenidate can be used to treat ADHD that co-occurs with tics, and can be used in combination with clonidine.[9][59] Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are used to manage anxiety and OCD.[9]

Other

Complementary and alternative medicine approaches, such as dietary modification, neurofeedback and allergy testing and control have popular appeal, but they have no proven benefit in the management of Tourette syndrome.[103][104] Despite this lack of evidence, up to two-thirds of parents, caregivers and individuals with TS use dietary approaches and alternative treatments and do not always inform their physicians.[19][89]

There is low confidence that tics are reduced with tetrahydrocannabinol,[14] and insufficient evidence for other cannabis-based medications in the treatment of Tourette's.[88] There is no good evidence supporting the use of acupuncture or transcranial magnetic stimulation; neither is there evidence supporting intravenous immunoglobulin, plasma exchange, or antibiotics for the treatment of PANDAS.[3]

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) has become a valid option for individuals with severe symptoms that do not respond to conventional therapy and management.[57] Selecting candidates who may benefit from DBS is challenging, and the appropriate lower age range for surgery is unclear.[6] The ideal brain location to target has not been identified as of 2019.[88][105]

Pregnancy

A quarter of women report that their tics increase before menstruation, however studies have not shown consistent evidence of a change in frequency or severity of tics related to pregnancy.[106][107] Overall, symptoms in women respond better to haloperidol than they do for men,[106] and one report found that haloperidol was the preferred medication during pregnancy,[107] to minimize the side effects in the mother, including low blood pressure, and anticholinergic effects.[108] Most women find they can withdraw from medication during pregnancy without much trouble.[107]

Prognosis

Tourette syndrome is a spectrum disorder—its severity ranges from mild to severe.[75] Symptoms typically subside as children pass through adolescence.[57] In a group of ten children at the average age of highest tic severity (around ten or eleven), almost four will see complete remission by adulthood. Another four will have minimal or mild tics in adulthood, but not complete remission. The remaining two will have moderate or severe tics as adults, but only rarely will their symptoms in adulthood be more severe than in childhood.[34]

Regardless of symptom severity, individuals with Tourette's have a normal life span. Symptoms may be lifelong and chronic for some, but the condition is not degenerative or life-threatening.[111] Intelligence among those with pure TS follows a normal curve, although there may be small differences in intelligence in those with comorbid conditions.[56] The severity of tics early in life does not predict their severity in later life.[30] There is no reliable means of predicting the course of symptoms for a particular individual,[84] but the prognosis is generally favorable.[84] By the age of fourteen to sixteen, when the highest tic severity has typically passed, a more reliable prognosis might be made.[96]

Tics may be at their highest severity when they are diagnosed, and often improve as an individual's family and friends come to better understand the condition. Studies report that almost eight out of ten children with Tourette's experience a reduction in the severity of their tics by adulthood,[9][34] and some adults who still have tics may not be aware that they have them. A study that used video to record tics in adults found that nine out of ten adults still had tics, and half of the adults who considered themselves tic-free displayed evidence of mild tics.[9][112]

Quality of life

People with Tourette's are affected by both the consequences of living with tics as well as efforts to suppress them.[113] Head and eye tics can interfere with reading or lead to headaches, and forceful tics can lead to repetitive strain injury.[114] Severe tics can lead to pain or injuries; as an example, a rare cervical disc herniation was reported from a neck tic.[41][59] Some people may learn to camouflage socially inappropriate tics or channel the energy of their tics into a functional endeavor.[31]

A supportive family and environment generally give those with Tourette's the skills to manage the disorder.[113][115][116] Outcomes in adulthood are associated more with the perceived significance of having severe tics as a child than with the actual severity of the tics. A person who was misunderstood, punished or teased at home or at school is likely to fare worse than a child who enjoyed an understanding environment.[31] The long-lasting effects of bullying and teasing can influence self-esteem, self-confidence, and even employment choices and opportunities.[113][117] Comorbid ADHD can severely affect the child's well-being in all realms, and extend into adulthood.[113]

Factors impacting quality of life change over time, given the natural fluctuating course of tic disorders, the development of coping strategies, and a person's age. As ADHD symptoms improve with maturity, adults report less negative impact in their occupational lives than do children in their educational lives.[113] Tics have a greater impact on adults' psychosocial function, including financial burdens, than they do on children.[96] Adults are more likely to report a reduced quality of life due to depression or anxiety;[113] depression contributes a greater burden than tics to adults' quality of life compared to children.[96] As coping strategies become more effective with age, the impact of OCD symptoms seems to diminish.[113]

Epidemiology

Tourette syndrome is a common but underdiagnosed condition that reaches across all social, racial and ethnic groups.[3][29][30][118] It is three to four times more frequent in males than in females.[53] Observed prevalence rates are higher among children than adults because tics tend to remit or subside with maturity and a diagnosis may no longer be warranted for many adults.[33] Up to 1% of the overall population experiences tic disorders, including chronic tics and transient (provisional or unspecified) tics in childhood.[47] Chronic tics affect 5% of children and transient tics affect up to 20%.[53][100]

Most individuals with tics do not seek a diagnosis, so epidemiological studies of TS "reflect a strong ascertainment bias" towards those with co-occurring conditions.[60] The reported prevalence of TS varies "according to the source, age, and sex of the sample; the ascertainment procedures; and diagnostic system",[29] with a range reported between 0.15% and 3.0% for children and adolescents.[53] Sukhodolsky, et al. wrote in 2017 that the best estimate of TS prevalence in children was 1.4%.[53] Both Robertson[36] and Stern state that the prevalence in children is 1%.[1] According to turn of the century census data, these prevalence estimates translate to half a million children in the US with TS and half a million people in the UK with TS, although symptoms in many older individuals would be almost unrecognizable.[lower-alpha 2]

Tourette syndrome was once thought to be rare: in 1972, the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) believed there were fewer than 100 cases in the United States,[119] and a 1973 registry reported only 485 cases worldwide.[120] However, numerous studies published since 2000 have consistently demonstrated that the prevalence is much higher.[121] Recognizing that tics may often be undiagnosed and hard to detect,[lower-alpha 3] newer studies use direct classroom observation and multiple informants (parents, teachers and trained observers), and therefore record more cases than older studies.[90][124] As the diagnostic threshold and assessment methodology have moved towards recognition of milder cases, the estimated prevalence has increased.[121]

History

A French doctor, Jean Marc Gaspard Itard, reported the first case of Tourette syndrome in 1825,[125] describing the Marquise de Dampierre, an important woman of nobility in her time.[126] In 1884, Jean-Martin Charcot, an influential French physician, assigned his student[127] and intern Georges Gilles de la Tourette, to study patients with movement disorders at the Salpêtrière Hospital, with the goal of defining a condition distinct from hysteria and chorea.[128] In 1885, Gilles de la Tourette published an account in Study of a Nervous Affliction of nine people with "convulsive tic disorder", concluding that a new clinical category should be defined.[129][130] The eponym was bestowed by Charcot after and on behalf of Gilles de la Tourette, who later became Charcot's senior resident.[24][131]

Following the 19th-century descriptions, a psychogenic view prevailed and little progress was made in explaining or treating tics until well into the 20th century.[24] The possibility that movement disorders, including Tourette syndrome, might have an organic origin was raised when an encephalitis lethargica epidemic from 1918 to 1926 was linked to an increase in tic disorders.[24][132]

During the 1960s and 1970s, as the beneficial effects of haloperidol on tics became known, the psychoanalytic approach to Tourette syndrome was questioned.[133] The turning point came in 1965, when Arthur K. Shapiro—described as "the father of modern tic disorder research"[134]—used haloperidol to treat a person with Tourette's, and published a paper criticizing the psychoanalytic approach.[132] In 1975, The New York Times headlined an article with "Bizarre outbursts of Tourette's disease victims linked to chemical disorder in brain", and Shapiro said: "The bizarre symptoms of this illness are rivaled only by the bizarre treatments used to treat it."[135]

During the 1990s, a more neutral view of Tourette's emerged, in which a genetic predisposition is seen to interact with non-genetic and environmental factors.[24][136][137] The fourth revision of the DSM (DSM-IV) in 1994 added a diagnostic requirement for "marked distress or significant impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning", which led to an outcry from TS experts and researchers, who noted that many people were not even aware they had TS, nor were they distressed by their tics; clinicians and researchers resorted to using the older criteria in research and practice.[11] In 2000, the American Psychiatric Association revised its diagnostic criteria in the fourth text revision of the DSM (DSM-IV-TR) to remove the impairment requirement,[74] recognizing that clinicians often see people who have Tourette's without distress or impairment.[78]

Society and culture

Not everyone with Tourette's wants treatment or a cure, especially if that means they may lose something else in the process.[93][138] The researchers Leckman and Cohen believe that there may be latent advantages associated with an individual's genetic vulnerability to developing Tourette syndrome that may have adaptive value, such as heightened awareness and increased attention to detail and surroundings.[139][140]

Accomplished musicians, athletes, public speakers and professionals from all walks of life are found among people with Tourette's.[77][141] The athlete Tim Howard, described by the Chicago Tribune as the "rarest of creatures—an American soccer hero",[142] and by the Tourette Syndrome Association as the "most notable individual with Tourette Syndrome around the world",[143] says that his neurological makeup gave him an enhanced perception and an acute focus that contributed to his success on the field.[110]

Samuel Johnson is a historical figure who likely had Tourette syndrome, as evidenced by the writings of his friend James Boswell.[144][145] Johnson wrote A Dictionary of the English Language in 1747, and was a prolific writer, poet, and critic. There is little support[146][147] for speculation that Mozart had Tourette's:[148] the potentially coprolalic aspect of vocal tics is not transferred to writing, so Mozart's scatological writings are not relevant; the composer's available medical history is not thorough; the side effects of other conditions may be misinterpreted; and "the evidence of motor tics in Mozart's life is doubtful".[149]

Likely portrayals of TS or tic disorders in fiction predating Gilles de la Tourette's work are "Mr. Pancks" in Charles Dickens's Little Dorrit and "Nikolai Levin" in Leo Tolstoy's Anna Karenina.[150] The entertainment industry has been criticized for depicting those with Tourette syndrome as social misfits whose only tic is coprolalia, which has furthered the public's misunderstanding and stigmatization of those with Tourette's.[151][152][153] The coprolalic symptoms of Tourette's are also fodder for radio and television talk shows in the US[154] and for the British media.[155] High-profile media coverage focuses on treatments that do not have established safety or efficacy, such as deep brain stimulation, and alternative therapies involving unstudied efficacy and side effects are pursued by many parents.[156]

Research directions

Research since 1999 has advanced knowledge of Tourette's in the areas of genetics, neuroimaging, neurophysiology, and neuropathology, but questions remain about how best to classify it and how closely it is related to other movement or psychiatric disorders.[3][8][9][10] Modeled after genetic breakthroughs seen with large-scale efforts in other neurodevelopmental disorders, three groups are collaborating in research of the genetics of Tourette's:

- The Tourette Syndrome Association International Consortium for Genetics (TSAICG)

- Tourette International Collaborative Genetics Study (TIC Genetics)

- European Multicentre Tics in Children Studies (EMTICS)

Compared to the progress made in gene discovery in certain neurodevelopmental or mental health disorders—autism, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder—the scale of related TS research is lagging in the United States due to funding.[157]

Notes

- According to Dale (2017), over time, 15% of people with tics have only TS (85% of people with Tourette's will develop a co-occurring condition).[9] In a 2017 literature review, Sukhodolsky, et al. stated that 37% of individuals in clinical samples had pure TS.[53] Denckla (2006) reported that a review of patient records revealed that about 40% of people with Tourette's have TS-only.[54][55] Dure and DeWolfe (2006) reported that 57% of 656 individuals presenting with tic disorders had tics uncomplicated by other conditions.[17]

- A prevalence range of 0.1% to 1% yields an estimate of 53,000 to 530,000 school-age children with Tourette's in the United States, using 2000 census data.[47] In the United Kingdom, a prevalence estimate of 1.0% based on the 2001 census meant that about half a million people aged five or older would have Tourette's, although symptoms in older individuals would be almost unrecognizable.[37]Prevalence rates in special education populations are higher.[36]

- The discrepancy between current and prior prevalence estimates arises from several factors: the ascertainment bias caused by samples that were drawn from clinically referred cases; assessment methods that failed to detect milder cases; and the use of different diagnostic criteria and thresholds.[121] There were few broad-based community studies published before 2000, and most older epidemiological studies were based only on individuals referred to tertiary care or specialty clinics.[122] People with mild symptoms may not have sought treatment and physicians may have avoided an official diagnosis of TS in children due to concerns about stigmatization.[38] Studies are vulnerable to further error because tics vary in intensity and expression, are often intermittent, and are not always recognized by clinicians, individuals with TS, family members, friends or teachers.[32][123]

References

- Stern JS (August 2018). "Tourette's syndrome and its borderland" (PDF). Pract Neurol (Historical review). 18 (4): 262–70. doi:10.1136/practneurol-2017-001755. PMID 29636375.

- "Tourette syndrome fact sheet". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. July 6, 2018. Archived from the original on December 1, 2018. Retrieved November 30, 2018.

- Hollis C, Pennant M, Cuenca J, et al. (January 2016). "Clinical effectiveness and patient perspectives of different treatment strategies for tics in children and adolescents with Tourette syndrome: a systematic review and qualitative analysis". Health Technology Assessment. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library. 20 (4): 1–450. doi:10.3310/hta20040. ISSN 1366-5278.

- "Tourette's Disorder, 307.23 (F95.2)". Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association. 2013. p. 81.

- Martino D, Hedderly T (February 2019). "Tics and stereotypies: A comparative clinical review". Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. (Review). 59: 117–24. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2019.02.005. PMID 30773283.

- Martino D, Pringsheim TM (February 2018). "Tourette syndrome and other chronic tic disorders: an update on clinical management". Expert Rev Neurother (Review). 18 (2): 125–37. doi:10.1080/14737175.2018.1413938. PMID 29219631.

- Jankovic J (September 2017). "Tics and Tourette syndrome" (PDF). Practical Neurology: 22–24. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 24, 2019. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- Fernandez TV, State MW, Pittenger C (2018). "Tourette disorder and other tic disorders". Handbook of Clinical Neurology (Review). 147: 343–54. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-63233-3.00023-3. ISBN 978-0-444-63233-3. PMID 29325623.

- Dale RC (December 2017). "Tics and Tourette: a clinical, pathophysiological and etiological review". Curr. Opin. Pediatr. (Review). 29 (6): 665–73. doi:10.1097/MOP.0000000000000546. PMID 28915150.

- Sukhodolsky, et al (2017), p. 242.

- Robertson MM, Eapen V (October 2014). "Tourette's: syndrome, disorder or spectrum? Classificatory challenges and an appraisal of the DSM criteria" (PDF). Asian J Psychiatr (Review). 11: 106–13. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2014.05.010. PMID 25453712.

- "Neurodevelopmental disorders". American Psychiatric Association. Archived from the original on May 10, 2011. Retrieved December 29, 2011.

- "Highlights of changes from DSM-IV-TR to DSM-5" (PDF). American Psychiatric Association. 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 3, 2013. Retrieved June 5, 2013.

- Pringsheim T, Holler-Managan Y, Okun MS, et al. (May 2019). "Comprehensive systematic review summary: Treatment of tics in people with Tourette syndrome and chronic tic disorders". Neurology (Review). 92 (19): 907–15. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000007467. PMC 6537130. PMID 31061209.

- "International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision: Chapter V: Mental and behavioural disorders". World Health Organization. 2010. Retrieved August 7, 2020. See also ICD version 2007.

- "Definitions and classification of tic disorders. The Tourette Syndrome Classification Study Group". Arch. Neurol. (Research support). 50 (10): 1013–16. October 1993. doi:10.1001/archneur.1993.00540100012008. PMID 8215958. Archived from the original on April 26, 2006.

- Dure LS, DeWolfe J (2006). "Treatment of tics". Adv Neurol (Review). 99: 191–96. PMID 16536366.

- Hashemiyoon R, Kuhn J, Visser-Vandewalle V (January 2017). "Putting the pieces together in Gilles de la Tourette Syndrome: exploring the link between clinical observations and the biological basis of dysfunction". Brain Topogr (Review). 30 (1): 3–29. doi:10.1007/s10548-016-0525-z. PMC 5219042. PMID 27783238.

- Ludlow AK, Rogers SL (March 2018). "Understanding the impact of diet and nutrition on symptoms of Tourette syndrome: A scoping review". J Child Health Care (Review). 22 (1): 68–83. doi:10.1177/1367493517748373. PMID 29268618.

- Sukhodolsky, et al (2017), p. 243.

- Jankovic J (2001). "Differential diagnosis and etiology of tics". Adv Neurol (Review). 85: 15–29. PMID 11530424.

- Ludolph AG, Roessner V, Münchau A, Müller-Vahl K (November 2012). "Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders in childhood, adolescence and adulthood". Dtsch Arztebl Int (Review). 109 (48): 821–28. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2012.0821. PMC 3523260. PMID 23248712.

- Muller-Vahl KR (2013) in Martino D, Leckman JF, eds, p. 629.

- Black KJ (March 30, 2007). "Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders". eMedicine. Archived from the original on August 22, 2009. Retrieved August 10, 2009.

- Miguel EC, do Rosário-Campos MC, Prado HS, et al. (February 2000). "Sensory phenomena in obsessive-compulsive disorder and Tourette's disorder". J Clin Psychiatry. 61 (2): 150–56, quiz 157. doi:10.4088/jcp.v61n0213. PMID 10732667.

- Prado HS, Rosário MC, Lee J, Hounie AG, Shavitt RG, Miguel EC (May 2008). "Sensory phenomena in obsessive-compulsive disorder and tic disorders: a review of the literature". CNS Spectr (Review and meta-anlysis). 13 (5): 425–32. doi:10.1017/s1092852900016606. PMID 18496480. Archived from the original on February 10, 2012.

- Bliss J (December 1980). "Sensory experiences of Gilles de la Tourette syndrome". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 37 (12): 1343–47. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780250029002. PMID 6934713.

- Kwak C, Dat Vuong K, Jankovic J (December 2003). "Premonitory sensory phenomenon in Tourette's syndrome". Mov. Disord. 18 (12): 1530–33. doi:10.1002/mds.10618. PMID 14673893.

- Swain JE, Scahill L, Lombroso PJ, King RA, Leckman JF (August 2007). "Tourette syndrome and tic disorders: a decade of progress". J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry (Review). 46 (8): 947–68. doi:10.1097/chi.0b013e318068fbcc. PMID 17667475.

- Singer HS (2011). "Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders". Hyperkinetic Movement Disorders (Historical review). Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 100. pp. 641–57. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-52014-2.00046-X. ISBN 978-0-444-52014-2. PMID 21496613. Also see Singer HS (March 2005). "Tourette's syndrome: from behaviour to biology". Lancet Neurol (Review). 4 (3): 149–59. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(05)01012-4. PMID 15721825.

- Leckman JF, Bloch MH, King RA, Scahill L (2006). "Phenomenology of tics and natural history of tic disorders". Adv Neurol (Historical review). 99: 1–16. PMID 16536348.

- Zinner SH (November 2000). "Tourette disorder". Pediatr Rev (Review). 21 (11): 372–83. doi:10.1542/pir.21-11-372. PMID 11077021.

- Leckman JF, Zhang H, Vitale A, et al. (July 1998). "Course of tic severity in Tourette syndrome: the first two decades" (PDF). Pediatrics (Research support). 102 (1 Pt 1): 14–19. doi:10.1542/peds.102.1.14. PMID 9651407. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 13, 2012.

- Fernandez TV, State MW, Pittenger C (2018). "Tourette disorder and other tic disorders". Handbook of Clinical Neurology (Review). 147: 343–54. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-63233-3.00023-3. ISBN 978-0-444-63233-3. PMID 29325623. Citing Bloch MH (2013) in Martino D, Leckman JF, eds, p. 109: No tics when they reach adulthood, 37%; minimal 18%; mild 26%; moderate 14%; worse 5%.

- Rapin I (2001). "Autism spectrum disorders: relevance to Tourette syndrome". Adv Neurol (Review). 85: 89–101. PMID 11530449.

- Robertson MM (February 2011). "Gilles de la Tourette syndrome: the complexities of phenotype and treatment". Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 72 (2): 100–07. doi:10.12968/hmed.2011.72.2.100. PMID 21378617.

- Robertson MM (November 2008). "The prevalence and epidemiology of Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Part 1: the epidemiological and prevalence studies". J Psychosom Res (Review). 65 (5): 461–72. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.03.006. PMID 18940377.

- Knight T, Steeves T, Day L, Lowerison M, Jette N, Pringsheim T (August 2012). "Prevalence of tic disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Pediatr. Neurol. (Review). 47 (2): 77–90. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2012.05.002. PMID 22759682.

- Kenney C, Kuo SH, Jimenez-Shahed J (March 2008). "Tourette's syndrome". Am Fam Physician (Review). 77 (5): 651–58. PMID 18350763.

- Black KJ, Black ER, Greene DJ, Schlaggar BL (2016). "Provisional Tic Disorder: What to tell parents when their child first starts ticcing". F1000Res (Review). 5. doi:10.12688/f1000research.8428.1. PMC 4850871. PMID 27158458.

- Robertson MM, Eapen V, Singer HS, et al. (February 2017). "Gilles de la Tourette syndrome" (PDF). Nat Rev Dis Primers (Review). 3: 16097. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2016.97. PMID 28150698.

- Kammer T (2007). "Mozart in the neurological department – who has the tic?" (PDF). Front Neurol Neurosci (Historical biography). Frontiers of Neurology and Neuroscience. 22: 184–92. doi:10.1159/000102880. ISBN 978-3-8055-8265-0. PMID 17495512. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 7, 2012.

- Todd O (2005). Malraux: A Life. Knopf.

- Guidotti TL (May 1985). "André Malraux: a medical interpretation". J R Soc Med (Historical biography). 78 (5): 401–06. doi:10.1177/014107688507800511. PMC 1289723. PMID 3886907.

- Bloch, State, Pittenger 2011. See also Schapiro 2002 and Coffey BJ, Park KS (May 1997). "Behavioral and emotional aspects of Tourette syndrome". Neurol Clin (Review). 15 (2): 277–89. doi:10.1016/s0733-8619(05)70312-1. PMID 9115461.

- >Hirschtritt ME, Lee PC, Pauls DL, et al. (April 2015). "Lifetime prevalence, age of risk, and genetic relationships of comorbid psychiatric disorders in Tourette syndrome". JAMA Psychiatry. 72 (4): 325–33. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2650. PMC 4446055. PMID 25671412.

- Scahill L, Williams S, Schwab-Stone M, Applegate J, Leckman JF (2006). "Disruptive behavior problems in a community sample of children with tic disorders". Adv Neurol (Comparative study). 99: 184–90. PMID 16536365.

- Morand-Beaulieu S, Leclerc JB, Valois P, et al. (August 2017). "A review of the neuropsychological dimensions of Tourette syndrome". Brain Sci (Review). 7 (8): 106. doi:10.3390/brainsci7080106. PMC 5575626. PMID 28820427.

- Sukhodolsky, et al (2017), p. 245.

- Hounie AG, do Rosario-Campos MC, Diniz JB, et al. (2006). "Obsessive-compulsive disorder in Tourette syndrome". Adv Neurol (Review). 99: 22–38. PMID 16536350.

- Cravedi E, Deniau E, Giannitelli M, et al. (2017). "Tourette syndrome and other neurodevelopmental disorders: a comprehensive review". Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health (Review). 11: 59. doi:10.1186/s13034-017-0196-x. PMC 5715991. PMID 29225671.

- Darrow SM, Grados M, Sandor P, et al. (July 2017). "Autism spectrum symptoms in a Tourette's disorder sample". J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry (Comparative study). 56 (7): 610–17.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2017.05.002. PMC 5648014. PMID 28647013.

- Sukhodolsky, et al (2017), p. 244.

- Denckla MB (August 2006). "Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) comorbidity: a case for "pure" Tourette syndrome?". J. Child Neurol. (Review). 21 (8): 701–03. doi:10.1177/08830738060210080701. PMID 16970871.

- Denckla MB (2006). "Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: the childhood co-morbidity that most influences the disability burden in Tourette syndrome". Adv Neurol (Review). 99: 17–21. PMID 16536349.

- Pruitt SK & Packer LE (2013) in Martino D, Leckman JF, eds, pp. 636–37.

- Baldermann JC, Schüller T, Huys D, et al. (2016). "Deep brain stimulation for Tourette syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Brain Stimul (Review). 9 (2): 296–304. doi:10.1016/j.brs.2015.11.005. PMID 26827109.

- Cavanna AE (November 2018). "The neuropsychiatry of Gilles de la Tourette syndrome: The état de l'art". Rev. Neurol. (Paris) (Review). 174 (9): 621–27. doi:10.1016/j.neurol.2018.06.006. PMID 30098800.

- Efron D, Dale RC (October 2018). "Tics and Tourette syndrome". J Paediatr Child Health (Review). 54 (10): 1148–53. doi:10.1111/jpc.14165. PMID 30294996.

- Bloch M, State M, Pittenger C (April 2011). "Recent advances in Tourette syndrome". Curr. Opin. Neurol. (Review). 24 (2): 119–25. doi:10.1097/WCO.0b013e328344648c. PMC 4065550. PMID 21386676.

- van de Wetering BJ, Heutink P (May 1993). "The genetics of the Gilles de la Tourette syndrome: a review". J. Lab. Clin. Med. (Review). 121 (5): 638–45. PMID 8478592.

- Paschou P (July 2013). "The genetic basis of Gilles de la Tourette Syndrome". Neurosci Biobehav Rev (Review). 37 (6): 1026–39. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.01.016. PMID 23333760.

- Barnhill J, Bedford J, Crowley J, Soda T (2017). "A search for the common ground between Tic; Obsessive-compulsive and Autism Spectrum Disorders: part I, Tic disorders". AIMS Genet (Review). 4 (1): 32–46. doi:10.3934/genet.2017.1.32. PMC 6690237. PMID 31435502.

- "PANDAS". National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on February 12, 2012. Retrieved November 25, 2006.

- Frick L, Pittenger C (2016). "Microglial dysregulation in OCD, Tourette syndrome, and PANDAS". J Immunol Res (Review). 2016: 8606057. doi:10.1155/2016/8606057. PMC 5174185. PMID 28053994.

- Hirschtritt ME, Darrow SM, et al. (January 2018). "Genetic and phenotypic overlap of specific obsessive-compulsive and attention-deficit/hyperactive subtypes with Tourette syndrome". Psychol Med. 48 (2): 279–93. doi:10.1017/S0033291717001672. PMID 28651666.

- Walkup, Mink & Hollenback (2006), p. xv.

- Sukhodolsky, et al (2017), p. 246.

- Cox JH, Seri S, Cavanna AE (May 2018). "Sensory aspects of Tourette syndrome" (PDF). Neurosci Biobehav Rev (Review). 88: 170–76. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.03.016. PMID 29559228.

- Rapanelli M, Pittenger C (July 2016). "Histamine and histamine receptors in Tourette syndrome and other neuropsychiatric conditions". Neuropharmacology (Review). 106: 85–90. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.08.019. PMID 26282120.

- Rapanelli M (February 2017). "The magnificent two: histamine and the H3 receptor as key modulators of striatal circuitry". Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry (Review). 73: 36–40. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2016.10.002. PMID 27773554.

- Bolam JP, Ellender TJ (July 2016). "Histamine and the striatum". Neuropharmacology (Review). 106: 74–84. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.08.013. PMC 4917894. PMID 26275849.

- Sadek B, Saad A, Sadeq A, Jalal F, Stark H (October 2016). "Histamine H3 receptor as a potential target for cognitive symptoms in neuropsychiatric diseases". Behav. Brain Res. (Review). 312: 415–30. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2016.06.051. PMID 27363923.

- Walkup JT, Ferrão Y, Leckman JF, Stein DJ, Singer H (June 2010). "Tic disorders: some key issues for DSM-V" (PDF). Depress Anxiety (Review). 27 (6): 600–10. doi:10.1002/da.20711. PMID 20533370. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 20, 2012.

- "What is Tourette syndrome?" (PDF). Tourette Association of America. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- Mejia NI, Jankovic J (March 2005). "Secondary tics and tourettism" (PDF). Braz J Psychiatry. 27 (1): 11–17. doi:10.1590/s1516-44462005000100006. PMID 15867978. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 28, 2007.

- Müller-Vahl KR (2013) in Martino D, Leckman JF, eds, p. 625.

- "Summary of Practice: Relevant changes to DSM-IV-TR". American Psychiatric Association. Archived from the original on May 11, 2008. Retrieved December 29, 2011.

- Martino D, Pringsheim TM, Cavanna AE, et al. (March 2017). "Systematic review of severity scales and screening instruments for tics: Critique and recommendations". Mov. Disord. (Review). 32 (3): 467–73. doi:10.1002/mds.26891. PMC 5482361. PMID 28071825.

- Sukhodolsky, et al (2017), p. 248.

- Scahill L, Erenberg G, Berlin CM, et al. (April 2006). "Contemporary assessment and pharmacotherapy of Tourette syndrome". NeuroRx (Review). 3 (2): 192–206. doi:10.1016/j.nurx.2006.01.009. PMC 3593444. PMID 16554257.

- Sukhodolsky, et al (2017), p. 247

- Bagheri MM, Kerbeshian J, Burd L (April 1999). "Recognition and management of Tourette's syndrome and tic disorders". Am Fam Physician (Review). 59 (8): 2263–72, 2274. PMID 10221310. Archived from the original on March 31, 2005.

- Singer HS (March 2005). "Tourette's syndrome: from behaviour to biology". Lancet Neurol (Review). 4 (3): 149–59. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(05)01012-4. PMID 15721825.

- Spencer T, Biederman J, Harding M, et al. (October 1998). "Disentangling the overlap between Tourette's disorder and ADHD". J Child Psychol Psychiatry (Comparative study). 39 (7): 1037–44. doi:10.1111/1469-7610.00406. PMID 9804036.

- Morand-Beaulieu S, Leclerc JB (January 2020). "[Tourette syndrome: Research challenges to improve clinical practice]". Encephale (in French). doi:10.1016/j.encep.2019.10.002. PMID 32014239.

- "Tourette syndrome treatments". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2019. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- Pringsheim T, Okun MS, Müller-Vahl K, et al. (May 2019). "Practice guideline recommendations summary: Treatment of tics in people with Tourette syndrome and chronic tic disorders". Neurology (Review). 92 (19): 896–906. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000007466. PMC 6537133. PMID 31061208.

- Müller-Vahl KR (2013) in Martino D, Leckman JF, eds, p. 628.

- Stern JS, Burza S, Robertson MM (January 2005). "Gilles de la Tourette's syndrome and its impact in the UK". Postgrad Med J (Review). 81 (951): 12–19. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2004.023614. PMC 1743178. PMID 15640424.

Reassurance, explanation, supportive psychotherapy, and psychoeducation are important and ideally the treatment should be multidisciplinary. In mild cases the previous methods may be all that is required, supplemented with contact with the Tourette Syndrome Association where the patient or parents wish.

- Robertson MM (March 2000). "Tourette syndrome, associated conditions and the complexities of treatment" (PDF). Brain (Review). 123 (Pt 3): 425–62. doi:10.1093/brain/123.3.425. PMID 10686169. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 14, 2007.

- Peterson BS, Cohen DJ (1998). "The treatment of Tourette's syndrome: multimodal, developmental intervention". J Clin Psychiatry (Review). 59 (Suppl 1): 62–74. PMID 9448671.

Because of the understanding and hope that it provides, education is also the single most important treatment modality that we have in TS.

Also see Zinner 2000, PMID 11077021. - Müller-Vahl KR (2013) in Martino D, Leckman JF, eds, pp. 623–24.

- Müller-Vahl KR (2013) in Martino D, Leckman JF, eds, p. 626. "Quite often, the unimpaired child receives medical treatment to reduce tics, when instead the parents should more appropriately receive psychoeducation and social support to better cope with the condition."

- Pruitt SK & Packer LE (2013) in Martino D, Leckman JF, eds, pp. 646–47.

- Müller-Vahl KR (2013) in Martino D, Leckman JF, eds, p. 627.

- Müller-Vahl KR (2013) in Martino D, Leckman JF, eds, p. 633.

- Fründt O, Woods D, Ganos C (April 2017). "Behavioral therapy for Tourette syndrome and chronic tic disorders". Neurol Clin Pract (Review). 7 (2): 148–56. doi:10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000348. PMC 5669407. PMID 29185535.

- Sudhodolsky, et al (2017), p. 250.

- Bloch MH, Leckman JF (December 2009). "Clinical course of Tourette syndrome". J Psychosom Res (Review). 67 (6): 497–501. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.09.002. PMC 3974606. PMID 19913654.

- Woods DW, Himle MB, Conelea CA (2006). "Behavior therapy: other interventions for tic disorders". Adv Neurol (Review). 99: 234–40. PMID 16536371.

- Sukhodolsky, et al (2017), p. 251.

- Zinner SH (August 2004). "Tourette syndrome—much more than tics" (PDF). Contemporary Pediatrics. 21 (8): 22–49. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 30, 2007. Retrieved May 20, 2019.

- Kumar A, Duda L, Mainali G, Asghar S, Byler D (2018). "A comprehensive review of Tourette syndrome and complementary alternative medicine". Curr Dev Disord Rep (Review). 5 (2): 95–100. doi:10.1007/s40474-018-0137-2. PMC 5932093. PMID 29755921.

- Viswanathan A, Jimenez-Shahed J, Baizabal Carvallo JF, Jankovic J (2012). "Deep brain stimulation for Tourette syndrome: target selection". Stereotact Funct Neurosurg (Review). 90 (4): 213–24. doi:10.1159/000337776. PMID 22699684.

- Rabin ML, Stevens-Haas C, Havrilla E, Devi T, Kurlan R (February 2014). "Movement disorders in women: a review". Mov. Disord. (Review). 29 (2): 177–83. doi:10.1002/mds.25723. PMID 24151214.

- Kranick SM, Mowry EM, Colcher A, Horn S, Golbe LI (April 2010). "Movement disorders and pregnancy: a review of the literature". Mov. Disord. (Review). 25 (6): 665–71. doi:10.1002/mds.23071. PMID 20437535.

- Committee on Drugs: American Academy of Pediatrics (April 2000). "Use of psychoactive medication during pregnancy and possible effects on the fetus and newborn". Pediatrics. 105 (4): 880–87. doi:10.1542/peds.105.4.880. PMID 10742343.

- Baxter, Kevin (October 5, 2019). "Column: Tim Howard, whose career is likely to end Sunday, will retire as the best U.S. goalkeeper ever". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- Howard T (December 6, 2014). "Tim Howard: Growing up with Tourette syndrome and my love of football". The Guardian. Archived from the original on November 15, 2016. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

- Novotny M, Valis M, Klimova B (2018). "Tourette syndrome: a mini-review". Front Neurol (Review). 9: 139. doi:10.3389/fneur.2018.00139. PMC 5854651. PMID 29593638.

- Pappert EJ, Goetz CG, Louis ED, Blasucci L, Leurgans S (October 2003). "Objective assessments of longitudinal outcome in Gilles de la Tourette's syndrome". Neurology. 61 (7): 936–40. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000086370.10186.7c. PMID 14557563.

- Evans J, Seri S, Cavanna AE (September 2016). "The effects of Gilles de la Tourette syndrome and other chronic tic disorders on quality of life across the lifespan: a systematic review". Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry (Review). 25 (9): 939–48. doi:10.1007/s00787-016-0823-8. PMC 4990617. PMID 26880181.

- Abi-Jaoude E, Kidecekl D, Stephens R, et al (2009), in Carlstedt RA (ed). p. 564.

- Leckman & Cohen (1999), p. 37. "For example, individuals who were misunderstood and punished at home and at school for their tics or who were teased mercilessly by peers and stigmatized by their communities will fare worse than a child whose interpersonal environment was more understanding and supportive."

- Cohen DJ, Leckman JF, Pauls D (1997). "Neuropsychiatric disorders of childhood: Tourette's syndrome as a model". Acta Paediatr Suppl. Scandinavian University Press. 422: 106–11. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.1997.tb18357.x. PMID 9298805.

The individuals with TS who do the best, we believe, are: those who have been able to feel relatively good about themselves and remain close to their families; those who have the capacity for humor and for friendship; those who are less burdened by troubles with attention and behavior, particularly aggression; and those who have not had development derailed by medication.

- Müller-Vahl KR (2013) in Martino D, Leckman JF, eds, p. 630.

- Gulati, S (2016). "Tics and Tourette Syndrome – Key Clinical Perspectives: Roger Freeman (ed)". Indian J Pediatr. 83 (11): 1361. doi:10.1007/s12098-016-2176-1.

Tic disorder is a common neurodevelopmental disorder of childhood. It is one of the commonest condition encountered by a pediatrician in office practice, especially in developed countries.

- Cohen, Jankovic & Goetz (2001), p. xviii.

- Abuzzahab FE, Anderson FO (June 1973). "Gilles de la Tourette's syndrome; international registry". Minn Med. 56 (6): 492–96. PMID 4514275.

- Scahill L. "Epidemiology of tic disorders" (PDF). Medical letter: 2004 retrospective summary of TS literature. Tourette Syndrome Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 25, 2010. Retrieved June 11, 2007.

- Bloch, State, Pittenger 2011. See also Zohar AH, Apter A, King RA, et al (1999). "Epidemiological studies" in Leckman & Cohen (1999), pp. 177–92.

- Hawley JS (June 23, 2008). "Tourette syndrome". eMedicine. Archived from the original on August 4, 2009. Retrieved August 10, 2009.

- Leckman JF (November 2002). "Tourette's syndrome". Lancet (Review). 360 (9345): 1577–86. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11526-1. PMID 12443611.

- Itard J (1825). "Mémoire sur quelques functions involontaires des appareils de la locomotion, de la préhension et de la voix". Arch Gen Med. 8: 385–407. As cited in Newman S (2006). "Study of several involuntary functions of the apparatus of movement, gripping, and voice by Jean-Marc Gaspard Itard (1825)" (PDF). History of Psychiatry. 17 (3): 333–39. doi:10.1177/0957154X06067668. PMID 17214432.

- "What is Tourette syndrome?". Tourette Syndrome Association. Archived from the original on January 14, 2012. Retrieved January 14, 2012.

- Walusinski (2019), pp. xvii–xviii, 23.

- Rickards H, Cavanna AE (2009). "Gilles de la Tourette: the man behind the syndrome". J Psychosom Res. 67 (6): 469–74. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.07.019. PMID 19913650.

- Gilles de la Tourette G, Goetz CG, Llawans HL (1982). "Étude sur une affection nerveuse caractérisée par de l'incoordination motrice accompagnée d'echolalie et de coprolalie". Advances in Neurology: Gilles de la Tourette Syndrome. 35: 1–16. As discussed at Black KJ (March 30, 2007). "Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders". eMedicine. Archived from the original on August 22, 2009. Retrieved August 10, 2009.

- Robertson MM, Reinstein DZ (1991). "Convulsive tic disorder: Georges Gilles de la Tourette, Guinon and Grasset on the phenomenology and psychopathology of Gilles de la Tourette syndrome" (PDF). Behavioural Neurology. 4 (1): 29–56. doi:10.1155/1991/505791. PMID 24487352.

- Walusinski (2019), pp. xi, 398. "Interne: House physician or house officer. The internes lived at the hospital and had diagnostic and therapeutic responsibilities. Chef de Clinique: Senior house officer or resident. In 1889, when Gilles de la Tourette was Chef de Clinique under Charcot ... "

- Blue T (2002). Tourette syndrome. Essortment, Pagewise Inc. Retrieved on August 10, 2009.

- Rickards H, Hartley N, Robertson MM (September 1997). "Seignot's paper on the treatment of Tourette's syndrome with haloperidol. Classic Text No. 31". Hist Psychiatry (Historical biography). 8 (31 Pt 3): 433–36. doi:10.1177/0957154X9700803109. PMID 11619589.

- Gadow KD, Sverd J (2006). "Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, chronic tic disorder, and methylphenidate". Adv Neurol (Review). 99: 197–207. PMID 16536367.

- Brody JE (May 29, 1975). "Bizarre outbursts of Tourette's disease victims linked to chemical disorder in brain". The New York Times. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- Kushner HI (2000), pp. 142–43, 187, 204, 208–12.

- Cohen DJ, Leckman JF (January 1994). "Developmental psychopathology and neurobiology of Tourette's syndrome". J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry (Review). 33 (1): 2–15. doi:10.1097/00004583-199401000-00002. PMID 8138517.

[Pathogenesis of tic disorders involves] interactions among genetic factors, neurobiological substrates, and environmental factors in the production of the clinical phenotypes. The genetic vulnerability factors that underlie Tourette's syndrome and other tic disorders undoubtedly influence the structure and function of the brain, in turn producing clinical symptoms. Available evidence ... also indicates that a range of epigenetic or environmental factors ... are critically involved in the pathogenesis of these disorders.

- Leckman & Cohen (1999), p. 408.

- Leckman & Cohen (1999), pp. 18–19, 148–51, 408.

- Müller-Vahl KR (2013) in Martino D, Leckman JF, eds. p. 624."... a few 'positive' aspects may be closely linked to TS. People with TS, for example, may have positive personality characterisics and talents such as punctuality, correctness, conscientiousness, a sense of justice, quick comprehension, good intelligence, creativity, musicality, and athletic abilities. For that reason, some people with TS even hesitate when asked whether they wish the disorder would disappear completely."

- Portraits of adults with TS. Tourette Syndrome Association. Retrieved from July 16, 2011 archive.org version on December 21, 2011.

- Keilman J (January 22, 2015). "Reviews: The Game of Our Lives by David Goldblatt, The Keeper by Tim Howard". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

- Tim Howard receives first-ever Champion of Hope Award from the National Tourette Syndrome Association. Archived March 30, 2015, at the Wayback Machine Tourette Syndrome Association. October 14, 2014. Retrieved on March 21, 2015.

- Samuel Johnson. Tourette Syndrome Association. Retrieved from April 7, 2005 archive.org version on December 30, 2011.

- Pearce JM (July 1994). "Doctor Samuel Johnson: 'the great convulsionary' a victim of Gilles de la Tourette's syndrome". J R Soc Med (Historical biography). 87 (7): 396–99. PMC 1294650. PMID 8046726.

- Powell H, Kushner HI (2015). "Mozart at play: the limitations of attributing the etiology of genius to tourette syndrome and mental illness". Prog. Brain Res. (Historical biography). 216: 277–91. doi:10.1016/bs.pbr.2014.11.010. PMID 25684294.

- Bhattacharyya KB, Rai S (2015). "Famous people with Tourette's syndrome: Dr. Samuel Johnson (yes) & Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (may be): Victims of Tourette's syndrome?". Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 18 (2): 157–61. doi:10.4103/0972-2327.145288. PMC 4445189. PMID 26019411.