A Clinical Lesson at the Salpêtrière

A Clinical Lesson at the Salpêtrière (French: Une leçon clinique à la Salpêtrière) is an 1887 group tableau portrait painted by the history and genre artist André Brouillet (1857–1914). The painting, one of the best-known in the history of medicine,[1] shows the neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot giving a clinical demonstration to a group of postgraduate students. Many of his students are identifiable; one is Georges Gilles de la Tourette, the physician who described Tourette syndrome.

| A Clinical Lesson at the Salpêtrière | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Pierre Aristide André Brouillet |

| Year | 1887 |

| Dimensions | 290 cm × 430 cm (110 in × 170 in) |

| Location | Paris Descartes University, Paris, France |

It hangs in a corridor of the Descartes University in Paris.

History

The painting is a large work—"remarkable for its dimensions, the figures being nearly life size"[2]—measuring 290 cm x 430 cm[3], and is painted in bright, highly contrasting colours.[4] It was painted by Brouillet at the age of thirty from individual studies made of the thirty participants,[5] and presented in the prevailing tradition of academic group portraits. It was first displayed (with favourable notices) at the salon d'art of 1 May 1887, and later purchased by the Académie des Beaux-Arts for 3,000 francs.[6]

Brouillet was a pupil of the academic painter Jean-Léon Gérôme who was, himself, also renowned for the fact that his paintings, such as Phryne before the Areopagus (1861), were so popular as prints that it seemed they were "painted in order to be reproduced".[7]

The setting

The painting represents an imaginary scene of a contemporary scientific demonstration, based on real life, and depicts the eminent French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot (1825-1893) delivering a clinical lecture and demonstration at the Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris (the room in which these demonstrations took place no longer exists at the Salpêtrière).[6]

On the rear wall of the lecture room is the (1878) large charcoal work, drawn by the anatomist and medical artist Paul Richer, which reproduces the hysterical pose captured in one of the many photographs taken in the Salpêtrière.

Entitled Periode de contortions ("During the contortions"), it depicts "a woman convulsing and assuming the arc-in-circle" posture:[6] the arc en circle, or Opisthotonus, "the hysteric's classic posture".[8]

Morloch (2007, p. 133), from his study of the actual painting, remarks on the striking and dramatic coincidence that, "in 1878 Richer reproduced the pose in [his] drawing from a photograph … [and] now, 1887 … the hysteric is reproducing in life the pose from the drawing."

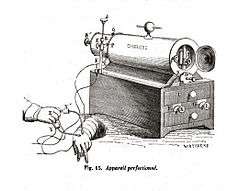

Resting on the table to Charcot's right "are a reflex hammer and what is thought to be a Duchenne electrotherapy apparatus".[6]

The participants

Except for the four individuals to Charcot's left, the participants are arranged in two concentric arcs: the inner circle displaying "sixteen of his current and former physician associates [arranged] in reverse order of seniority", and the outer, depicting "the older generation of [physician associates] … along with philosophers, writers, and friends of Charcot".[6]

Both Signoret (1983, p. 689) and Harris (2005, p. 471) have identified each of the individuals depicted in Brouillet's tableau; and Signoret (passim) provides substantial biographical details of each.

The Charcot group

The Charcot group of five are (from right-to-left): Mlle. Ecary, a nurse at the Salpêtrière; Marguerite Bottard, the Salpêtrière's nursing director; Joseph Babinski (1857–1933), Charcot's chief house officer; Marie "Blanche" Wittman, Charcot's patient; and Jean-Martin Charcot himself.

.jpg)

The inner window-side group

The six sitting in the window-side of the painting are (from right to left): Paul Richer (1849–1933), medical artist, anatomist and physician (who created the painting on the back wall); Charles Samson Féré (1852–1907), psychiatrist, Charcot's assistant, and Charcot's secretary; Pierre Marie (1853–1940), neurologist; Édouard Brissaud (1852–1909), neurologist and pathologist; Paul-Adrien Berbez (1859-?), physician, and a student of Charcot, and neurologist; and Gilbert Ballet (1853–1917), destined to be one of Charcot's last chief residents.

The outer window-side group

The six standing at the window-side of the painting are (from right to left): Alix Joffroy (1844–1908), anatomical pathologist, neurologist and psychiatrist; Jean-Baptiste Charcot (1867–1936), Charcot's son, at the time a medical student and, later, a polar explorer; Mathias-Marie Duval (1844–1907), Professor of anatomy and histology; Georges Maurice Debove (1845–1920), later Dean of the medical school; Philippe Burty, art collector, critic, and writer; and Victor André Cornil (1837–1908), pathologist, histologist, and politician.

The remaining group

The remainder are either sitting parallel to the back wall, or on the side of the lecture theatre immediately opposite the windows. The remaining thirteen individuals are (from left to right): Théodule-Armand Ribot (1839–1916), psychologist; Georges Guinon (1859–1932), neuropsychiatrist, and one of Charcot's last chief residents;[10] Albert Londe (1858–1917), medical photographer, and chronophotographer (wearing an apron); Léon Grujon Le Bas (1834–1907),[11] chief hospital administrator at Salpêtrière; Albert Gombault (1844–1904), neurologist and anatomist; Paul Arène (1843–1896), novelist; Jules Claretie (1840–1913), journalist and literary figure; Alfred Joseph Naquet (1834–1916), physician, chemist, and politician; Désiré-Magloire Bourneville (1840–1909), neurologist and politician; Henry Berbez (with pen and notebook), younger brother of Paul-Adrien Berbez (who is sitting opposite at the table); Henri Parinaud (1844–1905), ophthalmologist and neurologist; Romain Vigouroux (1831-1911), chief of electrodiagnostics, discoverer of the electrical activity of the skin (in the skull-cap);[12] and, finally, in the apron, Georges Gilles de la Tourette (1857–1904), neurologist and physician.

Current location

Apparently the painting has only recently returned to Paris, having "spent most of its life in obscurity in Nice and Lyon".[13]

Today it hangs, unframed, in a corridor of the Descartes University in Paris, near to the entrance of the Museum of the History of Medicine, which houses one of the oldest collections of surgical, diagnostic, and physiological instrumentation in Europe.[14]

Reproductions

In the nineteenth century, a considerable number of different versions of the original painting were produced.

Morloch's approximation (2007, p. 135) is that there were at least fifteen uniquely different reproductions produced by techniques as varied as "engraving, etching, lithograph(y), photogravure, along with other photomechanical processes" between the painting's first appearance in 1887, and its disappearance from public view in 1891.

Freud's lithograph

Sigmund Freud had a small (38.5 cm x 54 cm)[15] lithographic version of the painting, created by Eugène Pirodon (1824–1908), framed and hung on the wall of his Vienna rooms from 1886 to 1938.[13]

Once Freud reached England, it was immediately placed directly over the analytical couch in his London rooms.[16]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Une leçon clinique à la Salpêtrière. |

- Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital

- The Salpêtrière School of Hypnosis

- Other paintings on medical subjects:

- The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Deijman

- Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp

- The Gross Clinic

- The Agnew Clinic

Footnotes

- HIMETOP: History of Medicine Topographical Database: "Un Leçon Clinique à la Salpêtrière" (1887) by André Brouillet.

- Micale (2004), p. 74.

- Signoret (1983), p. 689.

- Morlock (2007), p. 129.

- Morlock (2007, p. 135) argues that most of these individual studies would have been taken by a photographer, rather than sketched by an artist. In support of his claim, Morlock draws attention to the "lack of interaction between the figures in the scene and the marked failures of their sightlines to meet".

- Harris (2005), p. 471.

- Morloch (2007), p. 134.

- Telson (1980), p. 58.

- The vertical crease in the middle of this image indicates that it has been taken from an (otherwise unidentified) bound volume and formed a double-page supplement.

- Georges Guinon (1859-1932), Bibliothèque nationale de France.

- A "chevalier de la Légion d'honneur", he was the illegitimate son of Philippe Le Bas. Originally known as Léon Grujon (Grujon was his mother's family name), he legally changed his name to Léon Grujon Le Bas on 25 June 1860 (Paris, L., État présent de la noblesse française, Bachelin-Deflorenne, 1866, p. 1169.)

- "Romain Vigouroux".

- Morlock (2007), p. 131.

- History of Medicine Topographical Database.

- Morlock (2007), p. 130.

- According to Morlock (2007, p. 130) — who suggests that "[it is almost] as if the painting itself was painted in order to be reproduced" — Pirodon's lithographic reproduction of Brouillet's original "was so successful that it was published at least three times by two separate printers".

References

- Alvarado, C. (May 2009). "Nineteenth-Century Hysteria and Hypnosis: A Historical Note on Blanche Wittmann" (PDF). Australian Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis. 37 (1): 21–36.

- Geisler, S. (2011). "Une Leçon Clinique à la Salpêtrière (A Clinical Lesson at the Salpêtrière), Andre Brouillet (1887)". The Journal of Physician Assistant Education. 22 (3): 41–42. doi:10.1097/01367895-201122030-00007. PMID 22070064.

- Harris, J.C. (May 2005). "A Clinical Lesson at the Salpêtrière". Archives of General Psychiatry. 62 (5): 470–472. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.5.470. PMID 15867099.

- Kemp, M.; Wallace, M. (2000). Spectacular Bodies: The Art and Science of the Human Body from Leonardo to Now. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Marshall, J. (January 2008). "Dynamic Medicine and Theatrical Form at the fin de siècle: A formal analysis of Dr Jean-Martin Charcot's pedagogy, 1862–1893". Modernism/Modernity. 15 (1): 131–153. doi:10.1353/mod.2008.0002.

- Micale, M.S. (2004). "Discourses of Hysteria in Fin-de-Siècle France". In Micale, M.S. (ed.). The Mind of Modernism: Medicine, Psychology, and the Cultural Arts in Europe and America, 1880-1940. Redwood City: Stanford University Press. pp. 71–92.

- Morlock, F. (March–June 2007). "The Very Picture of a Primal Scene: Une leçon clinique à la Salpêtrière". Visual Resources: An International Journal of Documentation. 23 (1–2): 129–146. doi:10.1080/01973760701219594.

- Signoret, J.L. (December 1983). "Une leçon clinique à la Salpêtrière (1887) par André Brouillet". Revue Neurologique. 139 (12): 687–701. PMID 6364290.

- Telson, H.W. (January 1980). "Une leçon du docteur Charcot à la Salpêtrière". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 35 (1): 58–59. doi:10.1093/jhmas/XXXV.1.58. PMID 6988496.

- Walusinski, O. (May 2011). "Marguerite Bottard (1822–1906), Nurse under Jean-Martin Charcot, Portrayed by G. Gilles de la Tourette". European Neurology. 65 (5): 279–285. doi:10.1159/000327313. PMID 21487229.