Dysgraphia

Dysgraphia is a deficiency in the ability to write, primarily handwriting, but also coherence.[1] Dysgraphia is a transcription disability, meaning that it is a writing disorder associated with impaired handwriting, orthographic coding, and finger sequencing (the movement of muscles required to write).[2] It often overlaps with other learning disabilities such as speech impairment, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, or developmental coordination disorder.[3] In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV), dysgraphia is characterized as a learning disability in the category of written expression when one's writing skills are below those expected given a person's age measured through intelligence and age-appropriate education. The DSM is not clear in whether or not writing refers only to the motor skills involved in writing, or if it also includes orthographic skills and spelling.[3]

| Dysgraphia | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Pediatrics, Psychiatry |

| Symptoms | Poor handwriting and spelling |

The word dysgraphia comes from the Greek words dys meaning "impaired" and γραφία graphía meaning "writing by hand".[2]

There are at least two stages in the act of writing: the linguistic stage and the motor-expressive-praxic stage. The linguistic stage involves the encoding of auditory and visual information into symbols for letters and written words. This is mediated through the angular gyrus, which provides the linguistic rules which guide writing. The motor stage is where the expression of written words or graphemes is articulated. This stage is mediated by Exner's writing area of the frontal lobe.[4]

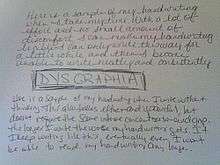

People with dysgraphia can often write on some level and may experience difficulty with other fine motor skills, such as tying shoes. However, dysgraphia does not affect all fine motor skills. People with dysgraphia often have unusual difficulty with handwriting and spelling[2] which in turn can cause writing fatigue.[3] They may lack basic grammar and spelling skills (for example, having difficulties with the letters p, q, b, and d), and often will write the wrong word when trying to formulate their thoughts on paper. The disorder generally emerges when the child is first introduced to writing.[2] Adults, teenagers, and children alike are all subject to dysgraphia.[5]

Dysgraphia should be distinguished from agraphia, which is an acquired loss of the ability to write resulting from brain injury, stroke, or progressive illness.[6]

Classification

Dysgraphia is nearly always accompanied by other learning disabilities such as dyslexia or attention deficit disorder,[2][7][8] and this can impact the type of dysgraphia a person might have. There are three principal subtypes of dysgraphia that are recognized. There is little information available about different types of dysgraphia and there are likely more subtypes than the ones listed below. Some children may have a combination of two or more of these, and individual symptoms may vary in presentation from what is described here. Most common presentation is a motor dysgraphia/agraphia resulting from damage to some part of the motor cortex in the parietal lobes.

Dyslexic

People with dyslexic dysgraphia have illegible spontaneously written work. Their copied work is fairly good, but their spelling is usually poor. Their finger tapping speed (a method for identifying fine motor problems) is normal, indicating that the deficit does not likely stem from cerebellar damage.

Motor

Motor dysgraphia is due to deficient fine motor skills, poor dexterity, poor muscle tone, or unspecified motor clumsiness. Letter formation may be acceptable in very short samples of writing, but this requires extreme effort and an unreasonable amount of time to accomplish, and it cannot be sustained for a significant length of time, as it can cause arthritis-like tensing of the hand. Overall, their written work is poor to illegible even if copied by sight from another document, and drawing is difficult. Oral spelling for these individuals is normal, and their finger tapping speed is below normal. This shows that there are problems within the fine motor skills of these individuals. People with developmental coordination disorder may be dysgraphic. Writing is often slanted due to holding a pen or pencil incorrectly.[2]

Spatial

A person with spatial dysgraphia has a defect in the understanding of space. They will have illegible spontaneously written work, illegible copied work, and problems with drawing abilities. They have normal spelling and normal finger tapping speed, suggesting that this subtype is not fine motor based.

Signs and symptoms

The symptoms to dysgraphia are often overlooked or attributed to the student being lazy, unmotivated, not caring, or having delayed visual-motor processing. In order to be diagnosed with dysgraphia, one must have a cluster, but not necessarily all, of the following symptoms:[2]

- Odd wrist, arm, body, or paper orientations such as bending an arm into an L shape

- Excessive erasures

- Mixed upper case and lower case letters

- Inconsistent form and size of letters, or unfinished letters

- Misuse of lines and margins

- Inefficient speed of copying

- Inattentiveness over details when writing

- Frequent need of verbal cues

- Relies heavily on vision to write

- Difficulty visualizing letter formation beforehand

- Poor legibility

- Poor spatial planning on paper

- Difficulty writing and thinking at the same time (creative writing, taking notes)

- Handwriting abilities that may interfere with spelling and written composition

- Difficulty understanding homophones and what spelling to use[9]

- Having a hard time translating ideas to writing, sometimes using the wrong words altogether

- May feel pain while writing (cramps in fingers, wrist and palms)[2]

Dysgraphia may cause students emotional trauma often due to the fact that no one can read their writing, and they are aware that they are not performing to the same level as their peers. Emotional problems that may occur alongside dysgraphia include impaired self-esteem, lowered self-efficacy, heightened anxiety, and depression.[2][7] They may put in extra efforts in order to have the same achievements as their peers, but often get frustrated because they feel that their hard work does not pay off.[7]

Dysgraphia is a hard disorder to detect as it does not affect specific ages, gender, or intelligence.[7] The main concern in trying to detect dysgraphia is that people hide their disability behind their verbal fluency because they are ashamed that they cannot achieve the same goals as their peers.[7] Having dysgraphia is not related to a lack of cognitive ability,[2] and it is not uncommon in intellectually gifted individuals, but due to dysgraphia their intellectual abilities are often not identified.[7]

Associated conditions

There are some common problems not related to dysgraphia but often associated with dysgraphia, the most common of which is stress. Often children (and adults) with dysgraphia will become extremely frustrated with the task of writing specially on plain paper (and spelling); younger children may cry, pout, or refuse to complete written assignments. This frustration can cause the child (or adult) a great deal of stress and can lead to stress-related illnesses. This can be a result of any symptom of dysgraphia.[5][7]

Causes

Dysgraphia is a biologically based disorder with genetic and brain bases.[2] More specifically, it is a working memory problem.[7] In dysgraphia, individuals fail to develop normal connections among different brain regions needed for writing.[7] People with dysgraphia have difficulty in automatically remembering and mastering the sequence of motor movements required to write letters or numbers.[2] Dysgraphia is also in part due to underlying problems in orthographic coding, the orthographic loop, and graphmotor output (the movements that result in writing) by one's hands, fingers and executive functions involved in letter writing.[2] The orthographic loop is when written words are stored in the mind's eye, connected through sequential finger movement for motor output through the hand with feedback from the eye.[7]

Diagnosis

Several tests exist to diagnose dysgraphia like Ajuriaguerra scale, BHK for children or teenagers, DASH and HHE scale.[10]

With devices like drawing tablets, it is now possible to measure the position, tilt, and pressure in real time. From these features, it is possible to compute automatic features like speed and shaking and train a classifier to diagnose automatically children with atypical writing.[10][11]

Treatment

Treatment for dysgraphia varies and may include treatment for motor disorders to help control writing movements. The use of occupational therapy can be effective in the school setting, and teachers should be well informed about dysgraphia to aid in carry-over of the occupational therapist's interventions. Treatments may address impaired memory or other neurological problems. Some physicians recommend that individuals with dysgraphia use computers to avoid the problems of handwriting. Dysgraphia can sometimes be partially overcome with appropriate and conscious effort and training.[2] The International Dyslexia Association suggests the use of kinesthetic memory through early training by having the child overlearn how to write letters and to later practice writing with their eyes closed or averted to reinforce the feel of the letters being written. They also suggest teaching the students cursive writing as it has fewer reversible letters and can help lessen spacing problems, at least within words, because cursive letters are generally attached within a word.

School

There is no special education category for students with dysgraphia;[2] in the United States, The National Center for Learning Disabilities suggests that children with dysgraphia be handled in a case-by-case manner with an Individualized Education Program, or provided individual accommodation to provide alternative ways of submitting work and modify tasks to avoid the area of weakness.[5] Students with dysgraphia often cannot complete written assignments that are legible, appropriate in length and content, or within given time.[2] It is suggested that students with dysgraphia receive specialized instructions that are appropriate for them. Children will mostly benefit from explicit and comprehensive instructions, help translating across multiple levels of language, and review and revision of assignments or writing methods.[7] Direct, explicit instruction on letter formation and guided practice will help students achieve automatic handwriting performance before they use letters to write words, phrases, and sentences.[2] Some older children may benefit from the use of a personal computer or a laptop in class so that they do not have to deal with the frustration of falling behind their peers.[7]

It is also suggested by Berninger that teachers with dysgraphic students decide if their focus will be on manuscript writing (printing) or keyboarding. In either case, it is beneficial that students are taught how to read cursive writing as it is used daily in classrooms by some teachers.[2] It may also be beneficial for the teacher to come up with other methods of assessing a child's knowledge other than written tests; an example would be oral testing. This causes less frustration for the child as they are able to get their knowledge across to the teacher without worrying about how to write their thoughts.[5]

The number of students with dysgraphia may increase from 4 percent of students in primary grades, due to the overall difficulty of handwriting, and up to 20 percent in middle school because written compositions become more complex. With this in mind, there are no exact numbers of how many individuals have dysgraphia due to its difficulty to diagnose.[2] There are slight gender differences in association with written disabilities; overall it is found that males are more likely to be impaired with handwriting, composing, spelling, and orthographic abilities than females.[7]

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 (DSM-5) doesn't use the term dysgraphia but uses the phrase "an impairment in written expression" under the category of "specific learning disorder". This is the term used by most doctors and psychologists.[12] To qualify for special education services, a child must have an issue named or described in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). While IDEA doesn't use the term "dysgraphia", it describes it under the category of "specific learning disability". This includes issues with understanding or using language (spoken or written) that make it difficult to listen, think, speak, read, write, spell or to do mathematical calculations.

See also

- Agraphia

- Character amnesia

- Dyscravia

- Learning disability

- Lists of language disorders

References

- Chivers, M. (1991). "Definition of Dysgraphia (Handwriting Difficulty). Dyslexia A2Z. Retrieved from http://www.dyslexiaa2z.com/learning_difficulties/dysgraphia/dysgraphia_definition.html Archived 2011-02-19 at the Wayback Machine

- Berninger, Virginia W.; Wolf, Beverly J. (2009). Teaching Students with Dyslexia and Dysgraphia: Lessons from Teaching and Science. Baltimore, Maryland: Paul H. Brooks Publishing Co. ISBN 978-1-55766-934-6.

- Nicolson, Roderick I.; Fawcett, Angela J. (January 2011). "Dyslexia, dysgraphia, procedural learning and the cerebellum". Cortex. 47 (1): 117–27. doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2009.08.016. PMID 19818437.

- Roux, Franck-Emmanuel; Dufor, Olivier; Giussani, Carlo; et al. (October 2009). "The graphemic/motor frontal area Exner's area revisited". Annals of Neurology. 66 (4): 537–45. doi:10.1002/ana.21804. PMID 19847902.

- "What is Dysgraphia?". National Center for Learning Disabilities. December 9, 2010. Archived from the original on August 7, 2012.

- "agraphia". the Free Dictionary by Farlex. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- Berninger, Virginia W.; O'Malley May, Maggie (2011). "Evidence-Based Diagnosis and Treatment for Specific Learning Disabilities Involving Impairments in Written and/or Oral Language". Journal of Learning Disabilities. 44 (2): 167–83. doi:10.1177/0022219410391189. PMID 21383108.

- "Bright Solutions - Free On-Line Videos". www.dys-add.com. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- Faust, Miriam (2012-02-13). The Handbook of the Neuropsychology of Language. Wiley - Blackwell. p. 912. ISBN 9781444330403. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- Asselborn, Thibault; Gargot, Thomas; Kidziński, Łukasz; Johal, Wafa; Cohen, David; Jolly, Caroline; Dillenbourg, Pierre (August 31, 2018). "Automated human-level diagnosis of dysgraphia using a consumer tablet" (PDF). Npj Digital Medicine. 1 (1): 42. doi:10.1038/s41746-018-0049-x. ISSN 2398-6352.

- Perrin, Sarah (September 28, 2018). "New software helps analyze writing disabilities". Medical Xpress.

- Patino, Erica. "Understanding Dysgraphia". Understood.org. Retrieved September 22, 2016.

Further reading

- Costa V, Fischer-Baum S, Capasso R, Miceli G, Rapp B (July 2011). "Temporal stability and representational distinctiveness: key functions of orthographic working memory". Cogn Neuropsychol. 28 (5): 338–62. doi:10.1080/02643294.2011.648921. PMC 3427759. PMID 22248210.

- Gergely K, Lakos R (February 2013). "[Role of pediatricians in the diagnosis and therapy of dyslexia, dysgraphia and dyscalculia]". Orv Hetil (in Hungarian). 154 (6): 209–18. doi:10.1556/OH.2013.29526. PMID 23376688.

- Martins MR, Bastos JA, Cecato AT, Araujo Mde L, Magro RR, Alaminos V (2013). "Screening for motor dysgraphia in public schools". J Pediatr (Rio J). 89 (1): 70–4. doi:10.1016/j.jped.2013.02.011. PMID 23544813.

- Purcell JJ, Turkeltaub PE, Eden GF, Rapp B (2011). "Examining the central and peripheral processes of written word production through meta-analysis". Front Psychol. 2: 239. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00239. PMC 3190188. PMID 22013427.