Tibradden Mountain

Tibradden Mountain (Irish: Sliabh Thigh Bródáin, meaning "mountain of the house of Bródáin")[4] is a mountain in County Dublin in Ireland. Other former names for the mountain include "Garrycastle" and "Kilmainham Begg" (a reference to Kilmainham Priory which once owned the lands around the mountain).[1] It is 467 metres (1,532 feet) high[2] and is the 561st highest mountain in Ireland.[3] It forms part of the group of hills in the Dublin Mountains which comprises Two Rock, Three Rock, Kilmashogue and Tibradden Mountains.[5] The views from the summit encompass Dublin to the north, Two Rock to the east and the Wicklow Mountains to the south and west.[6] The geological composition is mainly granite and the southern slopes are strewn with granite boulders.[7] The summit area is a habitat for heather, furze, gorse and bilberry as well as Sika deer, foxes and badgers.[7] The forestry plantation on the slopes – known as the Pine Forest – contains Scots pine, Japanese larch, European larch, Sitka spruce, oak and beech.[7] The mountain is also a site of archaeological interest with a prehistoric burial site close to the summit.

| Tibradden Mountain (Sliabh Thigh Bródáin) | |

|---|---|

| Garrycastle;[1] Kilmainhambegg[1] | |

Tibradden from Montpelier Hill | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 467 m (1,532 ft) [2] |

| Prominence | 30 m (98 ft) [3] |

| Coordinates | 53°14′19″N 6°16′49″W [2] |

| Geography | |

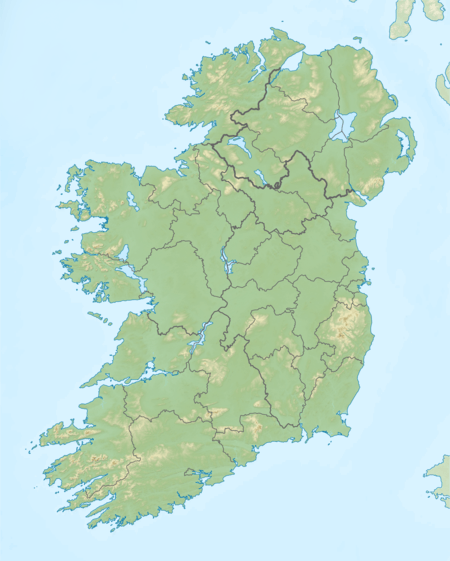

Tibradden Location in Ireland | |

| Location | County Dublin, Ireland |

| Parent range | Dublin Mountains |

| OSI/OSNI grid | O1487822281 |

| Topo map | OSI Discovery No. 50 |

History

Prehistoric monuments

Close to the summit is a prehistoric burial site. Local tradition associates it, incorrectly, with Niall Glúndub.[8] It was excavated in 1849 by members of the Royal Irish Academy who found a stone-lined cist containing a pottery vessel and cremated remains, now preserved by the National Museum of Ireland in Dublin.[9][10] In its present form, the site consists of an open circular chamber 10 feet (3.0 metres) in diameter with a narrow passage.[11] For many years, it was believed that this monument was a passage grave and the author Robert Graves refers to it as such in his poetic mythological work The White Goddess (1948).[12] However, conservation work done at the site in 1956 revealed that the chamber and passage were not original features but had probably been created at the time of the original excavation in the nineteenth century.[13] A stone bench was also found in the centre, apparently built for the convenience of visitors to the site.[14] It is now accepted that the monument is in fact a chambered cairn with a cist burial at the centre.[12][14] The site may be the burial place of Bródáin, after whom the mountain is named.[6][15] The monument is not at the summit of the mountain but is located slightly to the north at a position where the view across Dublin Bay to Howth is not obscured by Two Rock.[6] Within the chamber itself lies a stone with a spiral pattern.[16] It became a national monument in 1940.[17]

Other sites of historical interest

The antiquarian Weston St. John Joyce described a rude carving of a cross and a crowned figure with upraised arms on one of the rocks to the south of the summit.[18] This feature was also documented and photographed by the archaeologist Patrick Healy.[19] Although the cross is in an early Christian style, Joyce and Healy both surmised it and the figure to have been carved at some time in the nineteenth century.[18][19] Both carvings are still somewhat visible (the figure less so than the cross) but require direct light on the rock. On the southern slopes, along the R116 road is a stone with the inscription, “O'Connell's Rock, 23 July 1823”.[1] Daniel O'Connell gave an address to the local populace from this rock as they celebrated Garland Sunday that year.[1]

Access and recreation

Access to the mountain is possible via the Pine Forest, a Coillte-owned forest recreation area on the slopes of the mountain which is managed by the Dublin Mountains Partnership.[7] Tibradden is also traversed by the Dublin Mountains Way hiking trail that runs between Shankill and Tallaght while the Wicklow Way hiking trail runs to the southeast of the summit.[2] The first part of the Dublin Mountains Way to be completed was the section linking Tibradden, Kilmashogue and Cruagh forests and a dedication plaque marking its opening on 19 June 2009 by Mr Éamon Ó Cuív, T. D., Minister for Community, Rural and Gaeltacht Affairs can be found along the route of the Way in the Pine Forest.[20]

There is another dedication plaque in the Pine Forest, near the car park, marking the inauguration of the Dublin Mountains Partnership on 24 October 2008 by Mr Eamon Ryan, T. D., Minister for Communications, Energy and Natural Resources.[21]

See also

- List of mountains in Ireland

- Dublin-Wicklow Mountains

References

Notes

- Healy, p. 93

- Discovery Series No. 50 (Map). Ordnance Survey Ireland.

- "Tibradden Mountain". Mountain Views. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- "Tibradden Mountain". Placenames Database of Ireland. Department of Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- Healy, p. 105.

- Fourwinds, p. 154.

- "Tibradden Wood (Pine Forest)". Coillte Outdoors. Retrieved 29 July 2010.

- Curtis, p. 107.

- Healy, p.91.

- Fourwinds, p. 23.

- Healy, p. 92.

- Fourwinds, p. 153.

- Fourwinds, p. 23-24.

- "Tibradden (Chambered Cairn)". The Modern Antiquarian. Retrieved 30 July 2010.

- Joyce, p. 135

- Fourwinds, Tom. "Tibradden Cairn Rock Art, County Dublin". Megalithomania. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- 'The Irish Times', Saturday, 9 Nov 1940

- Joyce, p. 134-135.

- Healy, Rathfarnham Roads, p. 92-93.

- "New Volunteer Ranger Service launched in Dublin Mountains as major new walking trail project unveiled". Dublin Mountains Partnership. Retrieved 30 July 2010.

- "Viewpoint: The Dublin Mountains Partnership Newsletter" (PDF). Dublin Mountains Partnership. Spring 2009. p. 2. Retrieved 30 July 2010.

Bibliography

- Curtis, Edmund (March–May 1942). "Norse Dublin". Dublin Historical Record. Dublin: Old Dublin Society. 4 (3): 96–108. ISSN 0012-6861. JSTOR 30102592.

- Fourwinds, Tom (2006). Monu-mental About: Prehistoric Dublin. Dublin: Nonsuch Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-84588-560-1.

- Healy, Patrick (April 2005). Rathfarnham Roads (pdf). Dublin: South Dublin Libraries. ISBN 0-9547660-3-2. Retrieved 7 August 2010.

- Joyce, Weston St. John (1994) [first published 1912]. The Neighbourhood of Dublin. Dublin: Hughes and Hughes. ISBN 0-7089-9999-9.

- Discovery Series No. 50: Dublin, Kildare, Meath, Wicklow (Map) (6th ed.). 1:50,000. Discovery Series. Ordnance Survey Ireland. 2010. ISBN 978-1-907122-17-0.