Tibetan Army

The Tibetan Army (Tibetan: དམག་དཔུང་བོད་, Wylie: dmag dpung bod ) was the military force of Tibet after its de facto independence in 1912 until the 1950s. As a ground army modernised with the assistance of British training and equipment, it served as the de facto armed forces of the Tibetan government.

| Tibetan Army | |

|---|---|

| དམག་དཔུང་བོད་ dmag dpung bod | |

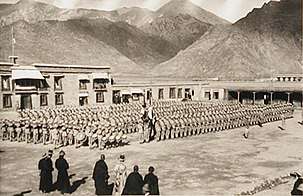

Soldiers of the Tibetan Army in Shigatse, 1938. | |

| Active | 1912–1950s |

| Country | |

| Role | Armed forces of Tibet |

| Size | c. 40,000 (including militias, 1934)[1] c. 10,000 (1936)[2] |

| Garrison/HQ | Lhasa, Tibet |

| Engagements | Bai Lang Rebellion Sino-Tibetan War Battle of Chamdo 1959 Tibetan uprising |

| Commanders | |

| Ceremonial chief | Dalai Lama |

| Notable commanders | 13th Dalai Lama (1912–1933) Tsarong Dazang Dramdul (1912–1925) |

Objectives

Internal

The Tibetan Army was established in 1913 by the 13th Dalai Lama, who had fled Tibet during the 1904 British invasion of Tibet and returned only after the fall of the Qing power in Tibet in 1911. During the revolutionary turmoil, the Dalai Lama had attempted to raise a volunteer army to expel all the ethnic Chinese from Lhasa, but failed, in large part because of the opposition of pro-Chinese monks, especially from the Drepung Monastery.[3] The Dalai Lama proceeded to raise a professional army, led by his trusted advisor Tsarong, to counter "the internal threats to his government as well as the external ones".[3][4]

The internal threats were mainly officials of the Gelug sect of Tibetan Buddhism, who feared British Christian and secular influence in the army, and who fought the defunding and taxing of the monasteries to feed military expenditures.[4] The monasteries had populations rivaling Tibet's largest cities, and had their own armies of dob-dobs ("warrior monks"). As a result, those monks who feared modernisation (associated with Britain) turned to China, which being the residence of the 9th Panchen Lama, portrayed itself as an ally to the Tibetan conservatives.[5] Residents evacuated the city during the Monlam Prayer Festival and Butter Lamp Festival of 1921, fearing violent confrontation between the monks and the Tibetan Army, which was eventually barred from Lhasa to keep the peace.[6]

The Army also received opposition from the 9th Panchen Lama, who refused the Dalai Lama's requests to fund the Tibetan Army from the monasteries in the Panchen's domain. In 1923, the Dalai Lama deployed troops to capture him, and so he secretly fled to Mongolia. The Dalai and Panchen Lamas exchanged many hostile letters during the latter's exile about the authority of the central Tibetan government. Many monks perceived the Panchen's exile as a consequence of the Dalai Lama's militarisation and secularisation of Tibet. The Dalai Lama himself grew gradually more distrustful of the military upon hearing rumours in 1924 of a coup conspiracy, which was supposedly designed to strip him of his temporal power.[3] In 1933, the 13th Dalai Lama died, and two regents assumed the head of government. The Tibetan Army was bolstered in 1937 by the perceived threat of the return of the Panchen Lama, who had brought arms back from eastern China.[4]

External

By the time of the 1949 Chinese Revolution, Chinese Communists had consolidated control over most of eastern China, and sought to bring peripheral areas such as Tibet back into the fold. China was aware of the threat of guerrilla warfare on Tibet's high mountains, and sought to resolve Tibet's political status by negotiations.[7] The Tibetan government stalled and delayed negotiations while bolstering its army.[7][8]

In 1950, the Kashag embarked on a series of internal reforms, led by Indian-educated officials. One of these reforms allowed the Kashag's military chiefs, Surkhang Wangchen Gelek and Ngapoi Ngawang Jigme, to act independently of the government. Although the Kashag appointed a "Governor of Kham", the Tibetan Army did not have effective control over Kham, whose local warlords had long resisted central control from Lhasa. As a result, Tibetan officials feared the local people, in addition to the People's Liberation Army (PLA) across the Upper Yangtze River.[8]

Military history

The Tibetan Army held the dominant military strength within political Tibet from 1912, owing to Chinese weakness because of the Japanese occupation of part of eastern China.[9][10] With the assistance of British training, it aimed to conquer territories inhabited by ethnic Tibetans but controlled by Chinese warlords,[11][12] and it successfully captured western Kham from the Chinese in 1917.[4] Its claim to adjacent territories controlled by British India, however, strained its vital relations with Britain and then independent India, and then China's relationship with the latter.[8][9] The 1914 Simla Accord with Britain was designed to settle Tibet's internal and external border issues, but for various reasons, including the refusal by the Chinese to accept it, warfare continued over territory in Kham.[3]

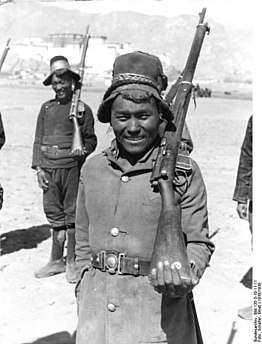

The military authority of Tibet was located in Chamdo (Qamdo) from 1918,[11] after it fell to Tibetan forces; during this time, the Sichuan warlords were occupied with fighting the Yunnan warlords, allowing the Tibetan army to defeat the Sichuan forces and conquer the region.[13] The Tibetan Army was involved in numerous border battles against the Kuomintang and Ma Clique forces of the Republic of China. By 1932, the defeat of the Tibetan Army by the KMT forces limited all meaningful political control of the Tibetan government over the Kham region beyond the Upper Yangtze River.[14] The Tibetan Army continued to expand its modern forces in the following years, and had about 5,000 regular soldiers armed with Lee–Enfield rifles in 1936. These troops were supported by an equal number of militiamen armed with older Lee–Metford rifles. In addition to these troops, who were mostly located along Tibet's eastern border, there was also Lhasa's garrison. The garrison included the Dalai Lhama's Bodyguard Regiment of 600 soldiers,[2] who were trained by British advisors,[12] 400 Gendarmerie, and 600 Kham regulars who were supposed to act as artillerymen, though they only had two functioning mountain guns.[2] Furthermore, the Tibetan Army had access to great numbers of locally raised village militias. These militias were often only armed with medieval weapons or matchlocks, and of negligible military value. Nevertheless, they could to hold their ground against the Chinese militias employed by the warlords.[15]

The Tibetan Army's first encounter with the PLA was in May 1950 at Dengo, ninety miles from Chamdo. 50 PLA soldiers captured Dengo, which gave strategic access to Jiegu. After ten days, Lhalu Tsewang Dorje ordered a contingent of 500 armed monks and 200 Khampa militiamen to recapture Dengo. According to the historian Tsering Shakya, the PLA attack could have been to either put pressure on the Kashag or to test the Tibetan defence forces.[8] Following repeated Tibetan refusals to negotiate,[7] the PLA advanced toward Chamdo, where most of the Tibetan Army was garrisoned. The army's ability to actually resist the PLA was severely limited by its inadequate equipment, the hostility of the local Khampas, and the behavior of the Tibetan government. At first, government officials did not react at all upon being informed of the Chinese advance, and then commanded Chamdo commander Ngapoi Ngawang Jigme to flee.[16] At this point, the Tibetan Army disintegrated and surrendered.[7][17]

Order of Battle, 1950

| Codename | Designation | Combat Arms | Personnel | Garrison | Armament |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kadam | 1st Dmag-Sgar | Cavalry | 1000 | Lhasa and Norbulingka | 8 mountain guns, 4 heavy machineguns, 46 LMGs, 200 Sten SMGs, 600 British-built rifles, several pistols |

| Khadam | 2nd Dmag-Sgar | Cavalry and Infantry | 1000 | Lhasa | 8 mountain guns, 8 mortars, 12 Lewis guns, 4 Maxim guns, 40 LMGs, 40 Sten SMGs, 900 British-built rifles |

| Gadam | 3rd Dmag-Sgar | Cavalry and Infantry | 1000 | Sibda | 14 cannons, 4 heavy machineguns, 4 Lewis guns, 16 Canadian Bren LMGs, 32 SMGs, 1000 rifles |

| Ngadam | 4th Dmag-Sgar | Cavalry and Infantry | 500 | Dêngqên | 1 heavy machinegun, 9 LMGs, 1 Lewis gun, 15 SMGs, 500 rifles |

| Cadam | 5th Dmag-Sgar | Cavalry and Infantry | 500 | Naqu | 2 heavy machineguns, 40 LMGs, 325 rifles |

| Chadam | 6th Dmag-Sgar | Artillery | 500 | Riwoqê | 6 cannons, 2 heavy machineguns, 10 LMGs, 15 SMGs, 400 rifles |

| Jadam | 7th Dmag-Sgar | Cavalry and Infantry | 500 | Riwoqê | 4 mountain guns, 2 heavy machineguns, 40 LMGs, 400 British-built rifles |

| Nyadam | 8th Dmag-Sgar | Cavalry and Infantry | 500 | Zhag'yab | 42 light/heavy machineguns, 500 rifles |

| Tadam | 9th Dmag-Sgar | Cavalry and Infantry | 500 | Mangkang | 42 light/heavy machineguns, 15 SMGs, 500 rifles |

| Thadam | 10th Dmag-Sgar | Cavalry and Infantry | 500 | Jiangda | 42 light/heavy machineguns, 500 rifles |

| Dadam | 11th Dmag-Sgar | Security | 500 | Lhasa | |

| Padam | 13th Dmag-Sgar | Cavalry and Infantry | 1500 | Lhari Town and Lhasa | |

| Phadam | 14th Dmag-Sgar | Cavalry and Infantry | 500 | Lhasa | |

| Badam | 15th Dmag-Sgar | Cavalry and Infantry | 500 | Sog County | |

| Madam | 16th Dmag-Sgar | Cavalry and Infantry | 500 | Shigatse | |

| Tsadam | 17th Dmag-Sgar | Cavalry and Infantry | 500 | Sog County |

- A dmag-sgar (Chinese: 玛噶) is equivalent to a regiment, while a mdav-dpon (Chinese: 代本) means the commander of a military unit.

- The 12th letter in the Tibetan alphabet, Na (Tibetan: ན ), means "illness", so the number was dropped.

- 11th to 17th Dmag-Sgar were formed from 1932 to 1949 and equipped with out-dated weapons, e.g. swords, spears, pistols, Russian muskets, and a few sub-machineguns and rifles[18][19]

Armaments

In 1950, the government also poured 400,000 rupees from the Potala treasury into its military, buying arms and ammunition from the British government, as well as the service of Indian military instructors.[8] For an additional 100,000 rupees, the Kashag purchased 38 2-inch mortars; 63 Ordnance ML 3 inch Mortars; 14,000 2-inch mortar bombs; 14,000 3-inch mortar bombs, 294 Bren guns, 1260 rifles; 168 Sten guns; 1,500,000 rounds of .303 ammunition, and 100,000 rounds of Sten gun ammunition. From India, the Kashag bought 3.5 million rounds of ammunition.[8]

However, the British were loath to create a too powerful Tibetan army, because of Tibet's irredentistic claims on British Indian territory.[9] The Indians were also irritated with Tibet's large outstanding debts for purchased arms, and hesitated to fulfill additional Tibetan requests for arms until previous supplies were paid for.[4]

In infrastructure, Lhasa established wireless base stations across the borderlands, such as Changtang (Qiangtang) and Chamdo.[8] In 1937, the Tibetan Army had 20 detachments along its eastern frontier comprising 10,000 troops with 5000 Lee–Enfield rifles and six Lewis guns. Smaller battalions were stationed in Lhasa, and adjacent to Nepal and Ladakh.[4] By 1949, 2500 Tibetan Army troops were stationed in Chamdo alone, and enlistment there increased by recruiting from Khampa militias.[8]

Advisors

In 1914, Charles Alfred Bell, a British civil servant who was posted to Tibet, recommended the militarisation of Tibet and the recruitment of 15,000 soldiers to guard against "foreign foes and internal disturbances".[6] The Tibetans eventually resolved to build a 20,000 man army, at a rate of 500 new recruits per year.[4] Bell told the Tibetan government that when China governed Tibet, it did so on terms not favourable to Tibet, and had tried to extend its influence over the Himalayan states (Sikkim, Bhutan, Ladakh), threatening British India. Also, Britain wanted a "barrier against Bolshevist influence". Under this reasoning, Bell proposed to the British government that Tibet be able to import munitions from India yearly; that the British government would provide training and equipment to Tibet; that British mining prospectors could inspect Tibet; and that an English school be established in Gyangze. By October 1921, all of the proposals were accepted.[4][6]

The government of Tibet had many foreigners in its employ, including Britons Reginald Fox, Robert W. Ford, Geoffrey Bull, and George Patterson; Austrians Peter Aufschnaiter and Heinrich Harrer; and the Russian Nedbailoff.[9] The army, in particular, had Japanese, Chinese, and British influence, although the British influence was of such an extent that the Tibetan officers gave their commands in English, and the Tibetan band played tunes including "God Save the King" and "Auld Lang Syne".[9]

From the fall of the Qing Dynasty, which had effectively controlled Tibet, to the 1949 Chinese Revolution, a Chinese mission remained in Lhasa. The mission repeatedly attempted to reestablish the office of the Qing Amban, interfered with the enthronement of the 13th Dalai Lama, and presented the Tibetan aristocratic government (Kashag) with a list of demands for the restoration of effective Chinese sovereignty.[8] Following the advice of British consul Hugh Richardson, the Kashag summoned Tibetan Army troops on 8 July 1949 from Shigatse and Dingri to expel all the Han Chinese people from Lhasa. The expulsion prompted Chinese accusations of a plot to turn Tibet into a British colony, and a consequent vow to "liberate" it.[8]

After 1951

After the Battle of Chamdo and the incorporation of Tibet into the People's Republic of China, the Tibetan Army kept its remaining force. By 1958 the Tibetan Army was composed of five dmag-sgars (regiments):

- 1st Dmag-Sgar

- 2nd Dmag-Sgar

- 3rd Dmag-Sgar

- 4th Dmag-Sgar

- 6th Dmag-Sgar

The 5th Dmag-Sgar, though it remained after 1951, was disbanded in 1957 because of the financial crisis of the Tibetan administration. The 9th Dmag-Sgar, which fought in the Battle of Chamdo, was incorporated into the People's Liberation Army (PLA) as the 9th Mdav-Dpon Infantry Regiment (Chinese: 第9代本步兵团) of the Tibet Military Region.

All but the 3rd Dmag-Sgar took part in the 1959 Tibetan uprising and were defeated by the People's Liberation Army. After the uprising, all remaining Tibetan Army units were disbanded, marking the end of the Tibetan Army.

The 9th Mdav-Dpon Infantry Regiment remained in the PLA order of battle until April 1970, when the regiment was officially disbanded.[18] The regiment took part in the suppression on 1959 Tibetan uprising and the Sino-Indian War.[20]

See also

References

Citations

- Jowett (2017), p. 241.

- Jowett (2017), p. 246.

- Goldstein, Melvyn (1991). A History of Modern Tibet, 1913-1951: The Demise of the Lamaist State. University of California Press. pp. 104, 113, 120, 131–135, 138.

- McCarthy, Roger (1997). Tears of the Lotus: Accounts of Tibetan Resistance to the Chinese Invasion, 1950-1962. McFarland. pp. 31–34, 38–39.

- Peissel, Michel (2003). Tibet: The Secret Continent. Macmillan. pp. 183–184.

- Bell, Charles (1992). Tibet Past and Present. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 185–188, 190–191.

- Goldstein, Melvyn (1999). The Snow Lion and the Dragon: China, Tibet, and the Dalai Lama. University of California Press. pp. 41, 44–45.

- Shakya, Tsering (1999). The Dragon in the Land of Shows: A History of Modern Tibet Since 1949. Columbia University Press. pp. 5–6, 8–9, 11–15, 26, 31, 38–40.

- Grunfeld, A. Tom (1996). The Making of Modern Tibet. M. E. Sharpe. pp. 79–81.

- Jowett (2017), p. 235.

- Alex McKay, (2003). The History of Tibet: The modern period: 1895-1959, the encounter with modernity. Routledge. ISBN 0415308445. pp. 275–276.

- Jowett (2017), p. 236.

- Jiawei Wang, (1997). The Historical Status of China's Tibet. Wuzhou Chuanbo Publishing. ISBN 7801133048. p. 136.

- Robert Barnett, Shirin Akiner, (1994). Resistance and Reform in Tibet. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 1850651612. pp. 83–90.

- Jowett (2017), pp. 243, 246.

- van Schaik (2013), pp. 209–212.

- van Schaik (2013), pp. 211, 212.

- 巴桑罗布: 藏军若千问题初探, 《中国藏学》 , 1992 (S1) :160-174

- 廖立: 中国藏军, 2007, ISBN 9787503424007, p.353-355

- 宋继琢:在起义藏军九代本担任军代表的日子(图), http://roll.sohu.com/20110521/n308165420.shtml

Sources

- Cited works

- Jowett, Philip S. (2017). The Bitter Peace. Conflict in China 1928–37. Stroud: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1445651927.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- van Schaik, Sam (2013). Tibet: A History. London, England; New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300194104.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Military of Tibet. |