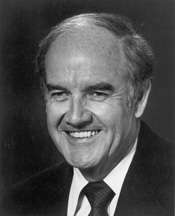

Thomas Eagleton

Thomas Francis Eagleton (September 4, 1929 – March 4, 2007) was a United States senator from Missouri, serving from 1968 to 1987. He is best remembered for briefly being the Democratic vice presidential nominee under George McGovern in 1972. He suffered from bouts of depression throughout his life, resulting in several hospitalizations, which were kept secret from the public. When they were revealed, it humiliated the McGovern campaign and Eagleton was forced to quit the race. He later became adjunct professor of public affairs at Washington University in St. Louis.

Thomas Eagleton | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States senator from Missouri | |

| In office December 28, 1968 – January 3, 1987 | |

| Preceded by | Edward V. Long |

| Succeeded by | Kit Bond |

| 38th Lieutenant Governor of Missouri | |

| In office January 11, 1965 – December 27, 1968 | |

| Governor | Warren E. Hearnes |

| Preceded by | Hilary A. Bush |

| Succeeded by | William S. Morris |

| 35th Attorney General of Missouri | |

| In office January 9, 1961 – January 11, 1965 | |

| Governor | John M. Dalton |

| Preceded by | John M. Dalton |

| Succeeded by | Norman H. Anderson |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Thomas Francis Eagleton September 4, 1929 St. Louis, Missouri, U.S. |

| Died | March 4, 2007 (aged 77) St. Louis, Missouri, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Barbara Ann Smith ( m. 1956) |

| Children | 2 |

| Education | Amherst College (BA) University of Oxford Harvard University (LLB) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1947-1949 |

Early life and political career

Eagleton was born in St. Louis, Missouri, the son of Zitta Louise (Swanson) and Mark David Eagleton, a politician who had run for mayor. His paternal grandparents were Irish immigrants, and his mother had Swedish, Irish, French, and Austrian ancestry.[1]

He graduated from St. Louis Country Day School, served in the U.S. Navy for two years, and graduated from Amherst College in 1950, where he was a member of Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity (Sigma Chapter). He then attended Harvard Law School. Following his graduation in 1953, Eagleton practiced law at his father's firm and later became associated with Anheuser-Busch's legal department.[2]

Eagleton married Barbara Ann Smith of St. Louis on January 26, 1956. A son, Terence, was born in 1959, and a daughter, Christin, was born in 1963.

He was elected circuit attorney of the City of St. Louis in 1956. During his tenure, he appeared on the TV show What's My Line? (episode #355) as "District Attorney of St. Louis". (He stumped the panel.)[3][4] He was elected Missouri Attorney General in 1960, at the age of 31 (the youngest in the state's history). He was elected the 38th Lieutenant Governor of Missouri in 1964, and won a U.S. Senate seat in 1968, unseating incumbent Edward V. Long in the Democratic primary and narrowly defeating Congressman Thomas B. Curtis in the general election.

Eagleton suffered from depression; he checked himself into hospital three times between 1960 and 1966 for physical and nervous exhaustion, receiving electroconvulsive therapy (shock therapy) twice.[5][6] He later received a diagnosis of bipolar II from Dr. Frederick K. Goodwin.[7]

The hospitalizations, which were not widely publicized, had little effect on his political aspirations, although the St. Louis Post-Dispatch was to note, in 1972, immediately after his vice presidential nomination: "He had been troubled with gastric disturbances, which led to occasional hospitalizations. The stomach troubles have contributed to rumors that he had a drinking problem."[6]

1972 presidential campaign

"Amnesty, abortion, and acid"

On April 25, 1972, as George McGovern won the Massachusetts Democratic primary, conservative journalist Robert Novak phoned Democratic politicians around the country. On April 27, 1972, Novak reported in a column his conversation with an unnamed Democratic senator about McGovern.[8][9]

Novak quoted the senator as saying "The people don't know McGovern is for amnesty, abortion, and legalization of pot. Once middle America—Catholic middle America, in particular—finds this out, he's dead."[8] Because of the column McGovern became known as the candidate of "amnesty, abortion, and acid,"[10][11] even though he only supported the decriminalization of marijuana and maintained that legalized abortion fell under the purview of states' rights.[12][13][14]

On July 15, 2007, several months after Eagleton's death, Novak said on Meet the Press that the unnamed senator was Eagleton.[11] Novak was accused in 1972 of manufacturing the quote, but stated that to rebut the criticism, he took Eagleton to lunch after the campaign and asked whether he could identify him as the source; the senator refused.[8] "Oh, he had to run for re-election", said Novak, "the McGovernites would kill him if they knew he had said that."[11] Political analyst Bob Shrum says that Eagleton would never have been selected as McGovern's running mate if it had been known at the time that Eagleton was the source of the quote.[11] "Boy, do I wish he would have let you publish his name. Then he never would have been picked as vice president," said Shrum.[11] "Because the two things, the two things that happened to George McGovern—two of the things that happened to him—were the label you put on him, number one, and number two, the Eagleton disaster. We had a messy convention, but he could have, I think in the end, carried eight or 10 states, remained politically viable. And Eagleton was one of the great train wrecks of all time."[11]

Selection as vice-presidential nominee

After a large number of prominent Democrats declined to be McGovern's running mate, Senator Gaylord Nelson (who was among those who declined) suggested Eagleton. McGovern chose Eagleton after only a minimal background check, as had been customary for vice presidential selections at that time.[15][16] Eagleton made no mention of his earlier hospitalizations, and in fact decided with his wife to keep them secret from McGovern while he was flying to his first meeting with McGovern.

Replacement on the ticket

On July 25, 1972, just over two weeks after the 1972 Democratic Convention, Eagleton admitted the truth of news reports that he had received electroshock therapy for clinical depression during the 1960s. McGovern initially said he would back Eagleton "1000 percent". Subsequently, McGovern consulted confidentially with preeminent psychiatrists, including Eagleton's own doctors, who advised him that a recurrence of Eagleton's depression was possible and could endanger the country should Eagleton become president.[17][18][19][20][21] On August 1, nineteen days after being nominated, Eagleton withdrew at McGovern's request and, after a new search by McGovern. In the book "The Life and Times of Sargent Shriver",by Scott Stossel (2004, Smithsonian Books) "a draft-Shriver movement had sprung up among the members of Congress who had recruited him to head the CLF in 1970. Led by George Mitrovich, an aide to New York congressman Lester Wolff and formerly a Robert F. Kennedy aide peppered McGovern headquarters with phone calls and telegrams. Shriver himself remained oddly diffident. Once, when Mitrovich called him, Shriver declined to take the call, saying he didn't want to interrrupt his dinner with Rose Kennedy. Another time, he refused to come off the tennis court to take a call. Mitrovich left an angry message: "What do you want to be-Wimbledon champ or Vice President of the United States?" Mitrovich's idea worked and Thomas Eagleton was replaced by Sargent Shriver, former U.S. Ambassador to France, and former (founding) Director of the Peace Corps and the Office of Economic Opportunity.[22]

A Time magazine poll taken at the time found that 77 percent of the respondents said "Eagleton's medical record would not affect their vote." Nonetheless, the press made frequent references to his 'shock therapy', and McGovern feared that this would detract from his campaign platform.[23]

McGovern's failure to thoroughly vet Eagleton[24] and his subsequent handling of the controversy gave occasion for the Republican campaign to raise serious questions about his judgment. In the general election, the Democratic ticket won only Massachusetts and the District of Columbia.

Re-election to Senate

Missouri returned Eagleton to the Senate in 1974; he won 60% of the popular vote against Thomas B. Curtis, who had been his opponent in 1968. In 1980, he was re-elected by a closer-than-expected margin over St. Louis County Executive Gene McNary.

During the 1980 election, Eagleton's niece Elizabeth Eagleton Weigand and lawyer Stephen Poludniak were arrested for blackmail after they threatened to spread false accusations that Eagleton was bisexual.[25][26] Eagleton told reporters that the extorted money was to be turned over to the Church of Scientology.[27] Poludniak and Weigand appealed the conviction all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, arguing that they could not have gotten a fair trial because of "the massive publicity surrounding this case, coupled with the pre-existing sentiment in favor of Sen. Eagleton". The Court turned down the appeal.

Eagleton did not seek a fourth term in 1986. Former Republican Governor Kit Bond succeeded him in the Senate. The seat remained in Republican hands following Bond's retirement when U.S. Representative Roy Blunt was elected in 2010 and re-elected in 2016.

Senate career

In the Senate, Eagleton was active in matters dealing with foreign relations, intelligence, defense, education, health care, and the environment. He was instrumental to the Senate's passage of the Clean Air Act and the Clean Water Act, and sponsored the amendment that halted the bombing in Cambodia and effectively ended American involvement in the Vietnam War.

Eagleton was one of the authors of The Hatch-Eagleton Amendment, introduced in the Senate on January 26, 1983 with Sen. Orrin Hatch (R), which stated that "A right to abortion is not secured by this Constitution".

Post-Senate career

In January 1987, Eagleton returned to Missouri as an attorney, political commentator, and professor at Washington University in St. Louis, where until his death he was professor of public affairs.[28][29] Throughout his Washington University career, Eagleton taught courses in economics with former chairman of the Council of Economic Advisors Murray Weidenbaum and with history professor Henry W. Berger on the Vietnam War.[29]

On July 23, 1996, Eagleton delivered a warm introductory speech for McGovern during a promotional tour for McGovern's book, Terry: My Daughter's Life-and-Death Struggle with Alcoholism, at The Library, Ltd., in St. Louis, Missouri. At that time, McGovern spoke favorably about Eagleton and reminisced about their short-lived presidential ticket in 1972.[30]

During the 2000s, Eagleton served on the Council of Elders for the George and Eleanor McGovern Center for Leadership and Public Service at Dakota Wesleyan University.[31]

In January 2001, he joined other Missouri Democrats to oppose the nomination of former governor and senator John Ashcroft for United States Attorney General. Eagleton was quoted in the official Judiciary Committee record: "John Danforth would have been my first choice. John Ashcroft would have been my last choice."[32]

In 2005 and 2006, he co-taught a seminar on the US presidency and the Constitution with Joel Goldstein at Saint Louis University School of Law. He was also a partner in the St. Louis law firm Thompson Coburn and was a chief negotiator for a coalition of local business interests that lured the Los Angeles Rams football team to St. Louis.[28][29] Eagleton authored three books on politics. Eagleton also strongly supported Democratic Senate candidate Claire McCaskill in 2006; McCaskill won, defeating incumbent Jim Talent.

Eagleton led a group, Catholics for Amendment 2, composed of prominent Catholics that challenged church leaders' opposition to embryonic stem cell research and to a proposed state constitutional amendment that would have protected such research in Missouri. The group e-mailed a letter to fellow Catholics explaining reasons for supporting Amendment 2.[33] The amendment ensures that any federally approved stem cell research and treatments would be available in Missouri. "[T]he letter from Catholics for Amendment 2 said the group felt a moral obligation to respond to what it called misinformation, scare tactics and distortions being spread by opponents of the initiative, including the church."[33]

Eagleton died in St. Louis on March 4, 2007, of heart and respiratory complications. Eagleton donated his body to medical science at Washington University.[34] He wrote a farewell letter to his family and friends months before he died, citing that his dying wishes were for people to "go forth in love and peace—be kind to dogs—and vote Democratic".[35]

Honors and awards

The 8th Circuit federal courthouse in St. Louis is named after Eagleton. Dedicated on September 11, 2000, it is named the Thomas F. Eagleton Building.

Eagleton has been honored with a star on the St. Louis Walk of Fame.[36]

In popular culture

Eagleton was referenced in the Netflix series The Politician, Season 1, Episode 2: "The Harrington Commode" as a comparison to a risky Vice Presidential candidate due to his history of depression and shock therapy treatment.

See also

References

- Noble, Barnes &. "Call Me Tom: The Life of Thomas F. Eagleton". Barnes & Noble. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- "C0674 Eagleton, Thomas F. (1929-2007), Papers, 1944-1987" (PDF). The State Historical Society of Missouri. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- TV.com. "What's My Line?: EPISODE #355". TV.com. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- What's My Line? (8 January 2014). "What's My Line? - Mamie Van Doren; Melvyn Douglas [panel] (Mar 24, 1957)". YouTube. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- Clymer, Adam (5 March 2007). "Thomas F. Eagleton, 77, a Running Mate for 18 Days, Dies". The New York Times.

- "St. Louis Post-Dispatch". Stltoday.com. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- Altman, Lawrence K. (July 23, 2012). "Hasty and Ruinous 1972 Pick Colors Today's Hunt for a No. 2". The New York Times. Retrieved June 24, 2017.

- Kraske, Steve (28 July 2007). "With another disclosure, Novak bedevils the dead". Kansas City Star. Archived from the original on 18 October 2007.

- Ganey, Terry (19 August 2007). "A slice of history: Biographers of the late U.S. Sen. Thomas Eagleton of Missouri will find some vivid anecdotes when they comb through his large collection of journals, letters and transcripts housed in Columbia". Columbia Tribune. Archived from the original on 7 June 2013.

- Riesel, Victor (6 July 1972). "Coalition Breaking". Rome News-Tribune. Rome, Georgia.

- "Interview with Robert Novak", Meet the Press, NBC News, 15 July 2007

- "Interview with Robert Novak", Meet the Press, NBC News, 2007-07-15. Retrieved 2011-01-21

- Ganey, Terry (August 19, 2007), "A slice of history", Columbia Tribune, archived from the original on June 7, 2013.

- Boller, Paul F., Presidential Campaigns: From George Washington to George W. Bush, Oxford University Press, 2004, pp. 339

- McGovern, George S., Grassroots: The Autobiography of George McGovern, New York: Random House, 1977, pp. 190-191

- Theodore White, The Making of the President, 1972, (1973), pp. 256-258

- McGovern, George S., Grassroots: The Autobiography of George McGovern, New York: Random House, 1977, pp. 214-215

- McGovern, George S., Terry: My Daughter's Life-and-Death Struggle with Alcoholism, New York: Random House, 1996, pp. 97

- Marano, Richard Michael, Vote Your Conscience: The Last Campaign of George McGovern, Praeger Publishers, 2003, pp. 7

- The Washington Post, "George McGovern & the Coldest Plunge", Paul Hendrickson, September 28, 1983

- The New York Times, "'Trashing' Candidates" (op-ed), George McGovern, May 11, 1983

- Theodore White, The Making of the President, 1972, (1973), pp. 260

- Garofoli, Joe (26 March 2008). "Obama bounces back – speech seemed to help". The San Francisco Chronicle.

- McGovern, George S., Grassroots: The Autobiography of George McGovern, New York: Random House, 1977, pp. 190-191

- Kohn, Edward (20 October 1980). "Eagleton's Reelection Bid Interrupted By Trial of Niece on Extortion Charge". Washington Post.

- "Around the Nation; Convictions Upheld In Eagleton Extortion". New York Times. 15 August 1981.

- Noble, Alice (23 October 1980). "A niece of Sen. Thomas F. Eagleton, D-Mo., testified..." UPI.

- Mannies, Jo (March 4, 2007). "Senator and statesman, Thomas Eagleton dies at 77". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Archived from the original on March 7, 2007. Retrieved December 25, 2019.

- "Thomas F. Eagleton, former U.S. senator and WUSTL professor of public affairs, dies at 77". The Record. Washington University in St. Louis. March 8, 2007. Archived from the original on March 18, 2007. Retrieved December 25, 2019.

- Video regarding My Daughter's Struggle with Alcoholism, St. Louis, Missouri: C-SPAN Video Library, 23 July 1996

- Council of Elders, McGovern Center for Leadership and Public Service, Dakota Wesleyan University

- Woods, Harriett (19 January 2001), Testimony For The Judiciary Committee Hearing On The Nomination of John Ashcroft, US Senate, archived from the original on 29 March 2007

- "Catholic group fights church leaders on stem cell research". CNN. 5 November 2006. Archived from the original on 6 November 2006.

- "The Record - The Source - Washington University in St. Louis". Record.wustl.edu. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- "Final wish: Be kind to dogs, vote Democratic". NBC News. Associated Press. 10 March 2007. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- St. Louis Walk of Fame. "St. Louis Walk of Fame Inductees". stlouiswalkoffame.org. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

Further reading

- Bormann, Ernest G. "The Eagleton affair: A fantasy theme analysis". Quarterly Journal of Speech 59.2 (1973): 143–159.

- Dickerson, John. "One of the Great Train Wrecks of All Time". Slate online magazine podcast 6/10/15

- Giglio, James N. Call Me Tom: The Life of Thomas F. Eagleton (University of Missouri Press; 2011) 328 pages

- Giglio, James N. "The Eagleton Affair: Thomas Eagleton, George McGovern, and the 1972 Vice Presidential Nomination", Presidential Studies Quarterly, (2009) 39#4 pp. 647–676

- Glasser, Joshua M. Eighteen-Day Running Mate: McGovern, Eagleton, and a Campaign in Crisis (Yale University Press, 2012). Comprehensive scholarly history

- Hendrickson, Paul. "George McGovern & the Coldest Plunge", The Washington Post, September 28, 1983

- Strout, Lawrence N. "Politics and mental illness: The campaigns of Thomas Eagleton and Lawton Chiles". Journal of American Culture 18.3 (1995): 67–73. doi:10.1111/j.1542-734X.1995.00067.x.

- Trent, Judith S., and Jimmie D. Trent. "The rhetoric of the challenger: George Stanley McGovern". Communication Studies 25#1 (1974): 11–18. doi:10.1080/10510977409367763.

- White, Theodore. The Making of the President, 1972 (1973)

- Time magazine—July 24, 1972 cover article

- Time magazine—August 7, 1972 cover on withdrawal

- "McGovern's First Crisis: The Eagleton Affair" Time August 7, 1972, cover story

- "George McGovern Finally Finds a Veep" Time August 14, 1972, cover story

External links

- United States Congress. "Thomas Eagleton (id: E000004)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- "Thomas Eagleton photographs". University of Missouri–St. Louis.

- Appearances on C-SPAN

| Legal offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by John M. Dalton |

Attorney General of Missouri 1961–1965 |

Succeeded by Norman H. Anderson |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Hilary A. Bush |

Lieutenant Governor of Missouri 1965–1968 |

Succeeded by William S. Morris |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by Edward V. Long |

Democratic nominee for U.S. Senator from Missouri (Class 3) 1968, 1974, 1980 |

Succeeded by Harriett Woods |

| Preceded by Edmund Muskie |

Democratic nominee for Vice President of the United States Withdrew 1972 |

Succeeded by Sargent Shriver |

| U.S. Senate | ||

| Preceded by Edward V. Long |

U.S. Senator (Class 3) from Missouri 1968–1987 Served alongside: Stuart Symington, John Danforth |

Succeeded by Kit Bond |