Chud

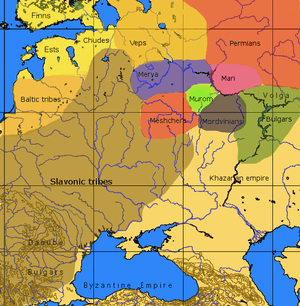

Chud or Chude (Old East Slavic: чудь, in Finnic languages: tšuudi, čuđit) is a term historically applied in the early East Slavic annals to several Baltic Finns in the area of what is now Estonia, Karelia[1] and Northwestern Russia.[2]

.png)

Perhaps the earliest written use of the term "Chudes" to describe Finnic peoples (presumably early Estonians) was c. 1100, in the earliest East Slavic chronicles.[3] According to the Primary Chronicle, Yaroslav I the Wise invaded the country of the Chudes in 1030 and laid the foundations of Yuryev (the historical Russian name of Tartu, Estonia).

According to Old East Slavic chronicles, the Chudes were among the founders of the Rus' state.[3]

Etymology

There are a number of hypotheses as to the origin of the term. Chude could be derived from the Slavic word tjudjo ('foreign' or 'strange'), which in turn is derived from the Gothic word meaning 'folk' (compare Teutonic). Another hypothesis is that the term was derived from a transformation of the Finno-Ugric name for the wood grouse. Yet another hypothesis contends that it is derived from the Sami word tshudde or čuđđe, meaning an enemy or adversary (fin. vainolainen).[4][5] This however would have required prominent Sami presence in trading centers around Lake Ladoga.[5]

Identity

Chudes have traditionally been believed to belong to the group of Baltic-Finnish peoples, though there have been some debate as to which specific group. After the first encounter with the Chudes, Slavic people tended to call other Finnic-speaking peoples Chudes, and thus became a collective name for the Finno-Ugric neighbours in Russian cultural tradition. Many writers contend that the Chudes were Vepsians, Fasmer posits them in Karelia while Smirnov suggests the Setos are descendants of the Chudes.[4] In recent research on toponymy of the Luga and Volkhov river catchment areas Finnish fennougrist Pauli Rahkonen has come to the conclusion, that the language spoken in the area has been Finnic only in the vicinity of the southern coasts of Lake Ladoga and the Gulf of Finland, but more upstream of the two rivers, the language, as based on the evidence of hydronyms in the area, has represented other Finno-Ugric languages than Finnic.[6] However, the Zavoloshka Chudes in the White Sea catchment area seem to have spoken Finnic languages based on the evidence of substrate toponymy in Northern Russia carried out recently by Finnish Finno-Ugrist Janne Saarikivi.[7]

Chudes in chronicles

The East Slavic Primary Chronicle describes Chudes as co-founders of the Rus' Khaganate state along with Krivichs, Veps, Ilmen Slavs and Vikings. In other ancient East Slavic chronicles, the term "Chudes" refers to several Finnic tribes, early Estonian groups in particular. In 1030, Prince Yaroslav the Wise of Kiev won a military campaign against the Chudes and established a fort in Yuryev (present day Tartu, in southeastern Estonia).[8] Kievan rulers then collected tribute from the Chudes of the surrounding ancient Estonian county of Ugaunia, possibly until 1061, when, according to the chronicles, Yuryev was burned down by Estonian tribe called Sosols (probably Sackalians, Oeselians or Harionenses).[9] Most of the raids against Chudes described in medieval East Slavic chronicles occur in present-day Estonia. The border lake between Estonia and Russia is still called Chudskoye (Chud Lake) in Russian. However, many ancient references to Chudes talk of peoples very far from Estonia, like Zavoloshka Chudes between Mordovians and Komis.

Chudes in folklore

In Russian folk legends, the Chudes were described as exalted and beautiful. One characteristic of the Chudes was 'white-eyed', which means lightly colored eyes.

Sorrowful Russian folk songs reminisce about the destruction of the Chudes when the Slavs were occupying their territories. When a Chude township was attacked, Chude women made themselves drown into the river with their jewels and children, in order not to be subjected to robbery or despoiling.

In the chronicles which narrate about the founding of Russia, the Chudes are mentioned as one of the founder races, with the Slav and the Varyags (Varangians).

Folk etymology derives the word from Old East Slavic language (chuzhoi, 'foreign'; or chudnoi 'odd'; or chud 'weird'), or alternatively from chudnyi, wonderful, miraculous, excellent, attractive.

Chudes or Tchudes are traditional generic villains in some Sami legends, as well as in the Sami-language movie Pathfinder from 1987, which is loosely based on such legends.[10]

Other sources suggest that ancient Chuds spoke a Finnic language similar to the Veps language.

Use of term in historical times

Later, the word Chudes was more often used for more eastern Finnic peoples, Veps and Votes in particular, while some derivatives of chud like chukhna or chukhonets were applied to more western Finns and Estonians. Following the Russian conquests of Finland 1714–1809, and increasing contacts between Finns and Saint Petersburg, Finns perceived the word Chud to be disparaging and hinting at the serfdom that the Russians were believed to find fit for the Finns. However, as a disparaging word, it was rather chukhna that was applied also to Finns (and likewise to Estonians) as late as during the Winter War, 1939–1940, between the Soviet Union and Finland.

In present-day Russian vernacular, the word chukhna is often used to denote the Veps. The name Chudes (or Northern Chudes) has been used for Veps people also by some anthropologists.

In the mytho-poetical tradition of the Komi, the word chud can also designate Komi heroes and heathens; Old Believers; another people different from the Komi; or robbers—the latter two are the typical legends in Sámi folklore. In fact, the legends about Chudes (Čuđit) cover a large area in northern Europe from Scandinavia to the Urals, bounded by Lake Ladoga in the south, the northern and eastern districts of the Vologda province, and passing by the Kirov region, further into Komi-Permyak Okrug. It has from this area spread to Trans-Ural region through mediation of migrants from European North.

Chude has become a swear word in the Arkhangelsk region. As late as 1920, people of that region used legends of the Chudes to scare small naughty children.[4]

See also

References

- Lind, John H. (2004). "The politico-religious landscape of medieval Karelia". Fennia. Helsinki. 182 (1): 3–11.

- Ryabinin, E. A. (1987). "The Chud of the Vodskaya Pyatina in the light of new discoveries" (PDF). Fennoscandia Archeologica: 87–104.

- Abercromby, John (1898). The Pre- and Proto-historic Finns. D. Nut. p. 13.

- Drannikova, Natalia; Roald Larsen (30 Sep 2008). "Representations of the Chudes in Norwegian and Russian Folklore". Acta Borealia. 25 (1): 58–72. doi:10.1080/08003830802302893.

- Uino, Pirjo (1997). Ancient Karelia. Helsinki: Suomen muinaismuistoyhdistyksen aikakausikirja 104. p. 101.

- Rahkonen, Pauli: Finno-Ugrian hydronyms of the River Volkhov and Luga catchment areas, pp. 205-266. Suomalais-Ugrilaisen Seuran Aikakauskirja – Journal de la Société Finno-Ougrienne 93. Helsinki: Finno-Ugric Society, 2011.

- Saarikivi, Janne: Substrata Uralica. Studies on finno-ugrian substrate in northern russian dialects. Archived 2017-08-30 at the Wayback Machine Tartu: Tartu University Press, 2006. ISBN 978-9949-11-474-0 ISBN 9949-11-474-8.

- Tvauri, Andres (2012). The Migration Period, Pre-Viking Age, and Viking Age in Estonia. pp. 33, 59, 60. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- Mäesalu, Ain (2012). "Could Kedipiv in East-Slavonic Chronicles be Keava hill fort?" (PDF). Estonian Journal of Archaeology. 1: 199. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- Mette Hjort, Ursula Lindqvist (2016). A Companion to Nordic Cinema. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1118475287.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 322.

- Savignac, David (trans). The Pskov 3rd Chronicle.