Tartus

Tartus (Arabic: طرطوس / ALA-LC: Ṭarṭūs; known in the County of Tripoli as Tortosa and also transliterated Tartous) is a city on the Mediterranean coast of Syria. It is the second largest port city in Syria (after Latakia), and the largest city in Tartus Governorate. The population is 115,769 (2004 census).[2] In the summer it is a vacation spot for many Syrians. Many vacation compounds and resorts are located in the region. The port holds a small Russian naval facility.

Tartous طرطوس Tartus | |

|---|---|

City | |

Tartus in May 2015 | |

| Nickname(s): trosom | |

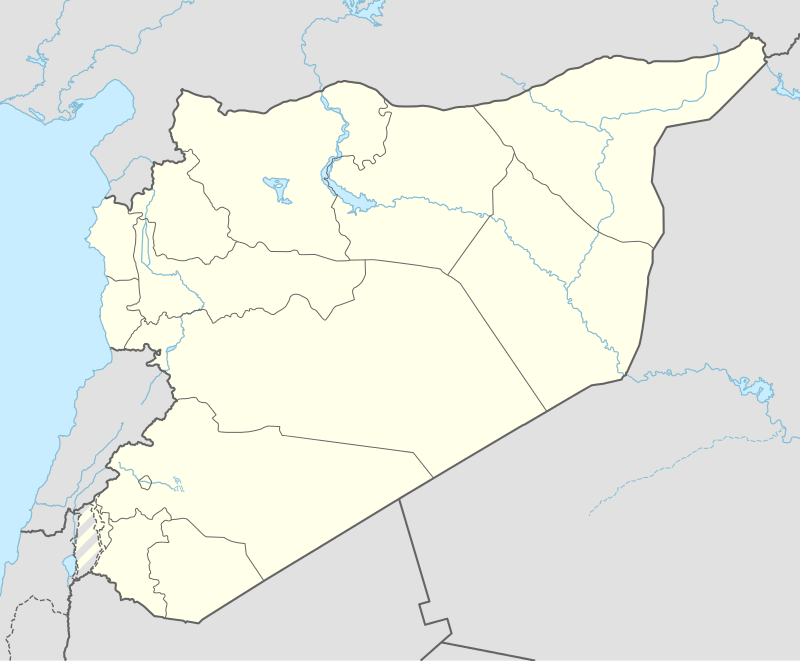

Tartous Location in Syria | |

| Coordinates: 34°53′N 35°53′E | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | Tartus |

| District | Tartus |

| Subdistrict | Tartus |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Wahib Hasan Zein Eddin |

| Elevation | 22 m (72 ft) |

| Population (2004 census)[1] | |

| • City | 115,769 |

| • Metro | 162,980 |

| Demonym(s) | Arabic: طرطوسي, romanized: Ṭarṭūsi |

| Area code(s) | 43 |

| Geocode | C5221 |

Geography

The city lies on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea bordered by the Syrian Coastal Mountain Range to the east. Arwad, the only inhabited island on the Syrian coast, is located a few kilometers off the shore of Tartus.

Tartus occupies most of the coastal plain, surrounded to the east by mountains composed mainly of limestone and, in certain places around the town of Souda, basalt.

Climate

Tartus has a Mediterranean climate (Köppen Csa) with mild, wet winters, hot and dry summers, and short transition periods in April and October. The hills to the east of the city create a cooler climate with even higher rainfall. Tartus is known for its relatively mild weather and high precipitation compared to inland Syria. Humidity in the summer can reach 0%.[3]

| Climate data for Tartus | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 15.8 (60.4) |

16.4 (61.5) |

18.6 (65.5) |

21.9 (71.4) |

24.8 (76.6) |

27.3 (81.1) |

29.2 (84.6) |

30.0 (86.0) |

29.2 (84.6) |

26.6 (79.9) |

22.4 (72.3) |

17.9 (64.2) |

23.34 (74.01) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 12.0 (53.6) |

12.7 (54.9) |

14.7 (58.5) |

17.6 (63.7) |

20.3 (68.5) |

23.9 (75.0) |

26.0 (78.8) |

26.7 (80.1) |

25.1 (77.2) |

21.9 (71.4) |

17.7 (63.9) |

13.7 (56.7) |

19.36 (66.85) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 8.4 (47.1) |

8.9 (48.0) |

10.4 (50.7) |

12.8 (55.0) |

15.6 (60.1) |

19.1 (66.4) |

22.2 (72.0) |

22.8 (73.0) |

20.4 (68.7) |

16.9 (62.4) |

13.2 (55.8) |

10.0 (50.0) |

15.06 (59.11) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 177.5 (6.99) |

142.1 (5.59) |

105.2 (4.14) |

57.1 (2.25) |

20.0 (0.79) |

12.3 (0.48) |

0.7 (0.03) |

3.8 (0.15) |

8.2 (0.32) |

67.6 (2.66) |

105.0 (4.13) |

184.8 (7.28) |

884.3 (34.81) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 12.5 | 10.2 | 9.3 | 5.4 | 2.1 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 4.4 | 6.5 | 11.0 | 62.9 |

| Source: Hong Kong Observatory[4] | |||||||||||||

History

Phoenician Antaradus

The History of Tartus goes back to the 2nd millennium BC when it was founded as a Phoenician colony of Aradus.[5] The colony was known as Antaradus (from Greek "Anti-Arados → Antarados", Anti-Aradus, meaning "The town facing Arwad"). Not much remains of the Phoenician Antaradus, the mainland settlement that was linked to the more important and larger settlements of Aradus, off the shore of Tartus, and the nearby site of Amrit.[6]

Greco-Roman and Byzantine

The city was called Antaradus in Latin. Athanasius reports that, under Roman Emperor Constantine the Great, Cymatius, the Orthodox bishop of Antaradus and also of Aradus (whose names indicate that they were neighbouring towns facing each other) was driven out by the Arians. At the First Council of Constantinople in 381, Mocimus appears as bishop of Aradus. At the time of the Council of Ephesus (431), some sources speak of a Musaeus as bishop of Aradus and Antaradus, while others mention only Aradus or only Antaradus. Alexander was at the Council of Chalcedon in 451 as bishop of Antaradus, Paulus as bishop of Aradus, while, at a synod held at Antioch shortly before, Paulus took part as bishop of both Aradus and Antaradus. In 458, Atticus signed, as bishop of Aradus, the letter of the bishops of the province of Phoenicia Prima to Byzantine Emperor Leo I the Thracian protesting about the murder of Proterius of Alexandria. Theodorus or Theodosius, who died in 518, is mentioned as bishop of Antaradus in a letter from the bishops of the province regarding Severus of Antioch that was read at a synod held by Patriarch Mennas of Constantinople. The acts of the Second Council of Constantinople in 553 were signed by Asyncretius as bishop of Aradus. At the time of the Crusades, Antaradus, by then called Tartus or Tortosa, was a Latin Church diocese, whose bishop also held the titles of Aradus and Maraclea (perhaps Rachlea). It was united to the see of Famagosta in Cyprus in 1295.[7][8][9]

No longer a residential bishopric, Antaradus is today listed by the Catholic Church as a titular see.[10]

The city was favored by Constantine for its devotion to the cult of the Virgin Mary. The first chapel to be dedicated to the Virgin is said to have been built here in the 3rd century.

Islamic

Muslim armies conquered Tartus under the leadership of Ubada ibn as-Samit in 636.

Crusades

The Crusaders called the city Antartus, and also Tortosa. It was captured in 1099 during the First Crusade, but it was later taken over by Muslims, before it was recaptured by Raymond of Saint-Gilles in February 1102 after two weeks of siege, then it was left in 1105 to his son Alfonso Jordan and was known as Tortosa. In 1123 the Crusaders built the semi-fortified Cathedral of Our Lady of Tortosa over a Byzantine church that was popular with pilgrims. The Cathedral itself was used as a mosque after the Muslim reconquest of the city, then as a barracks by the Ottomans. It was renovated under the French and is now the city museum, containing antiquities recovered from Amrit and many other sites in the region. Nur ad-Din Zangi retrieved Tartus from the Crusaders for a brief time before he lost it again.

In 1152, Tortosa was handed to the Knights Templar, who used it as a military headquarters. They engaged in some major building projects, constructing a castle with a large chapel and an elaborate keep, surrounded by thick double concentric walls.[11] The Templars' mission was to protect the city and surrounding lands, some of which had been occupied by Christian settlers, from Muslim attack. The city of Tortosa was recaptured by Saladin in 1188, and the main Templar headquarters relocated to Cyprus. However, in Tortosa, some Templars were able to retreat into the keep, which they continued to use as a base for the next 100 years. They steadily added to its fortifications until it also fell, in 1291. Tortosa was the last outpost of the Templars on the Syrian mainland, after which they retreated to a garrison on the nearby island of Arwad, which they held for another decade.

Civil war

On May 23, 2016, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant claimed responsibility for three suicide bombings at a bus station in Tartus, which had remained largely unaffected since the Syrian Civil War began in 2011. Purportedly targeting Alawite gatherings, the bombs killed 48 people. In Jableh, similarly insulated, another four bombers killed over a hundred people.[12]

Economy, transportation and navy

Tartus is an important trade center in Syria and has one of the two main ports of the country on the Mediterranean. The city port is experiencing major expansion as a lot of Iraqi imports come through the port of Tartus to aid reconstruction efforts in Iraq.

Tartus is a destination for tourists. The city has sandy beaches and several resorts. The city has seen some investments in the last few years. The largest being Antaradus and Porto waterfront development.[13]

Tartus has a well-developed road network and highways. The Chemins de Fer Syriens operated railway network connects Tartus to major cities in Syria, although only the Latakia-Tartus passenger connection is in service.

Russian naval base

Tartus hosts a Soviet-era naval supply and maintenance base, under a 1971 agreement with Syria, which is still staffed by Russian naval personnel. Tartus is the last Russian military base outside the former Soviet Union, and its only Mediterranean fueling spot, sparing Russia's warships the trip back to their Black Sea bases through straits in Turkey, a NATO member.[14]

Main sights

The historic centre of Tartus consists of more recent buildings built on and inside the walls of the Crusader-era Templar fortress, whose moat still separates this old town from the modern city on its northern and eastern sides. Outside the fortress few historic remains can be seen, with the exception of the former cathedral of Notre-Dame of Tartus (Our Lady of Tortosa), from the 12th century. The church is now the site of a museum.

Tartus and the surrounding area are rich in antiquities and archeological sites. Various important and well known sites are located within a 30-minute drive from Tartus. These attractions include:

- The old city of Tartus.

- Marqab Castle, north of the city.

- The historic Town of Safita.

- Arwad island and castle.

- The ancient cathedral of Our Lady of Tortosa, now used as the city museum.

- Beit el-Baik Palace.

- Hosn Suleiman Temple.

- Mashta Al Helou resort.

- Drekish town-resort.

The outlying town of Al Hamidiyah just south of Tartus is notable for having a Greek-speaking population of about 3,000 who are the descendants of Ottoman Greek Muslims from the island of Crete but usually confusingly referred to as Cretan Turks. Their ancestors moved there in the late 19th century as refugees from Crete after the Kingdom of Greece acquired the island from the Ottoman Empire following the Greco-Turkish War of 1897.[15] Since the start of the Iraqi War, a few thousands Iraqi nationals now reside in Tartus.

Notable people

- Saadallah Wannous (1941–1997), playwright and first Arab to deliver the International Theatre Day address.

- Sheikh Saleh Al-Ali, pre-independence Syrian revolutionary who fought against the French mandate.

- Dr. Halim Barakat, novelist, sociologist and retired research professor.[16]

- Mohammad Yousaf Abu al-Farah Tartusi, Muslim saint of the Junaidia order[17]

- Jamal Suliman, actor.

- Taim Hasan, actor.

- Farrah Yousef, singer and Arab Idol Season 2 finalist.

References

- Tartus city population

- "Syria: largest cities and towns and statistics of their population". World-gazetteer.com. Archived from the original on 2007-10-01. Retrieved August 4, 2010.

- "Central Bureau of Statistics". Cbssyr.org. Archived from the original on April 28, 2007. Retrieved August 4, 2010.

- "Climatological Information for Tartous, Syria". Hong Kong Observatory. June 2011.

- Tartus Encyclopaedia of the Orient. Retrieved 2007, 06-26.

- History of Tartous Archived 2007-07-04 at the Wayback Machine Syria Gate. Retrieved 2007, 06-26.

- Pius Bonifacius Gams, Series episcoporum Ecclesiae Catholicae, Leipzig 1931, p. 434

- Michel Lequien, Oriens christianus in quatuor Patriarchatus digestus, Paris 1740, Vol. II, coll. 827-830

- Konrad Eubel, Hierarchia Catholica Medii Aevi, vol. 1, p. 92; vol. 2, p. XII and 89

- Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2013 ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 833

- Lost Worlds: Knights Templar. History Channel video documentary, first aired July 10, 2006.

- "IS blasts in Syria regime heartland kill more than 148", by AFP, via Channel NewsAsia

- "antaradus.com". antaradus.com. Retrieved 2020-05-29.

- Kramer, Andrew E. (June 18, 2012). "Russian Warships Said to Be Going to Naval Base in Syria". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 20, 2012. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

- Greek-Speaking Enclaves of Lebanon and Syria by Roula Tsokalidou. Proceedings II Simposio Internacional Bilingüismo. Retrieved December 4, 2006.

- "Halim Barakat". Halim Barakat. Retrieved August 4, 2010.

- Sultan Mohammad Najib-ur-Rehman. "Sultan-Bahoo-The-Life-and-Teachings". Sultan-ul-Faqr Publications Regd. ISBN 9789699795183.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tartus. |

- Articles, stories and posts about Tartous (Tartus)

- Sea Side by Mariyah and Abufares. A novel with the backdrop of the Syrian coast and Tartous

- tartous-city.com

- Tartus Port

- Abufares said... the world according to a Tartoussi, an English blog from Tartous

- eTartus - a website for Tartus news and services