Rape in the Hebrew Bible

| Part of a series on the |

| Bible |

|---|

|

|

Perspectives |

|

Outline of Bible-related topics |

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity and gender |

|---|

"Adam and Eve" by Albrecht Dürer (1504) |

|

Theology

|

|

Major positions |

|

Other positions |

|

Denominational teaching |

|

Church and society |

|

Theologians and authors (by view) |

|

Theologians and authors (by branch) |

Passages

In Mosaic law

Mosaic law has been interpreted by Frank M. Yamada as addressing rape in Deuteronomy 22:23-29,[1] presenting three distinct laws on the issue. The passage is as follows:

If a damsel that is a virgin be betrothed unto an husband, and a man find her in the city, and lie with her; Then ye shall bring them both out unto the gate of that city, and ye shall stone them with stones that they die; the damsel, because she cried not, being in the city; and the man, because he hath humbled his neighbour's wife: so thou shalt put away evil from among you.

But if a man find a betrothed damsel in the field, and the man force her, and lie with her: then only the man that lay with her shall die. But unto the damsel thou shalt do nothing; there is in the damsel no sin worthy of death: for as when a man riseth against his neighbour, and slayeth him, even so is this matter: For he found her in the field, and the betrothed damsel cried, and there was none to save her.

If a man find a damsel that is a virgin, which is not betrothed, and lay hold on her, and lie with her, and they be found; Then the man that lay with her shall give unto the damsel's father fifty shekels of silver, and she shall be his wife; because he hath humbled her, he may not put her away all his days.[2]

Yamada opines that Deuteronomy 22:23-24, which commands punishment for the woman if the act takes place in the city, was not about rape, but adultery, because the woman was already considered to be the reserved property of a future husband. He also argued that although the laws treat women as property, "the Deuteronomic laws, even if they do not address the crime of rape as sexual violence against a woman as such, do provide a less violent alternative for addressing the situation.[3]

Deuteronomy in historical biblical authorities

Many modern translations interpret Deuteronomy 22:28-29 as referring to a case of rape.

Other instances

There are several other passages in the Old Testament, including Genesis 34, Numbers 31:15-18, Deuteronomy 21:10-14, Judges 19:22-26, and 2 Samuel 13:1-14, which depict rape or have been interpreted as discussing rape by numerous scholars, including Wil Gafney and Phyllis Trible.[4][5] In Genesis 34, Dinah is abducted by Shechem in a passage that is often interpreted as rape.[6][7] In Numbers 31:15-18, Moses, after exacting revenge on the Midianites, commands his army to kill all the boys and every non-virgin woman while telling them to "save for [themselves]" every virgin woman," a phrase which has been interpreted as a passage depicting rape.[4][8] Judges 19:22-26 depicts Gibeah and the Levite Concubine, in which a man sends out his concubine to a group of angry men, where they gang rape her.[9] Afterwards, the man cuts up the body of his concubine into twelve pieces and sends them to the Twelve Tribes of Israel.[4][10] 2 Samuel 13:1-14 involves the rape of Tamar.[11][12]

Analysis

In The Bible Now, Richard Elliott Friedman and Shawna Dolansky write "What should not be in doubt is the biblical view of rape: it is horrid. It is decried in the Bible's stories. It is not tolerated in the Bible's laws."[13]

Genesis

Genesis 19

Genesis 19 features an attempted gang rape. Two angels arrive in Sodom, and Lot shows them hospitality. However, the men of the city gathered around Lot's house and demanded that he give them the two guests so that they could rape them. In response to this, Lot offers the mob his two virgin daughters instead. The mob refuses Lot's offer, but the angels strike them with blindness, and Lot and his family escape.

Genesis 19 goes on to relate how Lot's daughters get him drunk and have sex with him. A number of commentators describe their actions as rape. Esther Fuchs suggests that the text presents Lot's daughters as the "initiators and perpetrators of the incestuous 'rape'."[14]

Gerda Lerner has suggested that because the Hebrew Bible takes for granted Lot's right to offer his daughters for rape, we can assume that it reflected a historical reality of a father's power over them.[15]

Genesis 34

Shechem's rape of Dinah in Genesis 34 is described in the text itself as "a thing that should not be done."[16] Sandra E. Rapoport argues that "The Bible text is sympathetic to Shechem in the verses following his rape of Dinah, at the same time that it does not flinch from condemning the lawless predatory behavior towards her. One midrash even attributes Shechem's three languages of love in verse 3 to God's love for the Children of Israel."[17] She also put forth that "Shechem's character is complex. He is not easily characterized as unqualifiedly evil. It is this complexity that creates unbearable tension for the reader and raises the justifiably strong emotions of outrage, anger, and possible compassion."[18]

Susanne Scholz writes that "The brothers' revenge, however, also demonstrates their conflicting views about women. On the one hand they defend their sister. On the other hand they do not hesitate to capture other women as if these women were their booty. The connection of the rape and the resulting revenge clarifies that no easy solutions are available to stop rapists and rape-prone behavior. In this regard Genesis 34 invites contemporary readers to address the prevalence of rape through the metaphoric language of a story."[19] In a different work, Scholz writes that "During its extensive history of interpretation, Jewish and Christian interpreters mainly ignored Dinah. […] in many interpretations, the fraternal killing is the criminal moment, and in more recent years scholars have argued explicitly against the possibility that Shechem rapes Dinah. They maintain that Shechem's love and marriage proposal do not match the 'scientifically documented behavior of a rapist'."[20][21] Mary Anna Bader notes the division between verses 2 and 3, and writes that "It is strange and upsetting for the modern reader to find the verbs 'love' and 'dishonor' together, having the same man as their subject and the same woman as their object."[22] Later, she writes that "The narrator gives the reader no information about Dinah's thoughts or feelings or her reactions to what has taken place. Shechem is not only the focalizor but also the primary actor…The narrator leaves no room for doubt that Shechem is the center of these verses. Dinah is the object (or indirect object) of Shechem's actions and desires."[23]

Sandra E. Rapoport regards Genesis 34 as condemning rape strongly, writing, "The brothers' revenge killings of Shechem and Hamor, while they might remind modern readers of frontier justice and vigilantism, are an understandable measure-for-measure act in the context of the ancient Near East.[24] Scholz argued that "The literary analysis showed, however, that despite this silence Dinah is present throughout the story. Indeed, everything happens because of her. Informed by feminist scholarship, the reading does not even require her explicit comments."[25]

Frank M. Yamada argues that the abrupt transition between Genesis 34:2 and 34:3 was a storytelling technique due to the fact that the narrative focused on the men, a pattern which he perceives in other rape narratives as well, also arguing that the men's responses are depicted in a mixed light. "The rape of Dinah is narrated in a way that suggests there are social forces at work, which complicate the initial seal violation and will make problematic the resulting male responses. […] The abrupt transition from rape to marriage, however, creates a tension in the reader's mind…the unresolved issue of punishment anticipates the response of Simeon and Levi."[26]

Genesis 39

In Genesis 39, a rare Biblical instance of sexual harassment and assault perpetrated against a man by a woman can be found. In this chapter, the enslaved Joseph endures repeated verbal sexual harassment from the wife of his master Potiphar. Joseph refuses to have sex with her, as he has no right to do so and it would be a sin against God (Genesis 39:6-10). Potiphar's wife eventually physically assaults him, demanding that he come to bed with her and grabbing at his clothing (Genesis 39:12). Joseph escapes, leaving the article of clothing with her (different translations describe the article of clothing as, for example, Joseph's "garment," "robe," "coat," or even simply "clothes"). Potiphar's wife then tells first her servants, and then her husband, that Joseph had attacked her (Genesis 39:13-18). Joseph is sent to prison (Genesis 39:19-20), where he remains until his God-given ability to interpret dreams leads the Pharaoh to ask for his help (Genesis 41:14).

Numbers 31

- ""Moses, Eleazar the priest, and all the leaders of the people went to meet them outside the camp. But Moses was furious with all the military commanders who had returned from the battle. “Why have you let all the women live?” he demanded. “These are the very ones who followed Balaam’s advice and caused the people of Israel to rebel against the LORD at Mount Peor. They are the ones who caused the plague to strike the LORD’s people. Now kill all the boys and all the women who have slept with a man. Only the young girls who are virgins may live; you may keep them for yourselves."

Deuteronomy

Deuteronomy 20–21

Deuteronomy 20:14 indicates that all women and child captives become enslaved property:

But the women, and the little ones, and the cattle, and all that is in the city, even all the spoil thereof, shalt thou take unto thyself; and thou shalt eat the spoil of thine enemies, which the Lord thy God hath given thee.

Deuteronomy 21:10–14 states:

When thou goest forth to war against thine enemies, and the Lord thy God hath delivered them into thine hands, and thou hast taken them captive, And seest among the captives a beautiful woman, and hast a desire unto her, that thou wouldest have her to thy wife; Then thou shalt bring her home to thine house, and she shall shave her head, and pare her nails; And she shall put the raiment of her captivity from off her, and shall remain in thine house, and bewail her father and her mother a full month: and after that thou shalt go in unto her, and be her husband, and she shall be thy wife. And it shall be, if thou have no delight in her, then thou shalt let her go whither she will; but thou shalt not sell her at all for money, thou shalt not make merchandise of her, because thou hast humbled her.

This passage is grouped with laws concerning sons and inheritance, suggesting that the passage's main concern is with the regulation of marriage in such a way as to transform the woman taken captive in war into an acceptable Israelite wife, in order to beget legitimate Israelite children. Caryn Reeder notes, "The month-long delay before the finalization of the marriage would thus act in part as a primitive pregnancy test." It

The idea that the captive woman will be raped is supported by the fact that in passages like Isaiah 13:16 and Zechariah 14:2, sieges lead to women being "ravished".[27] M.I. Rey notes that the passage "conveniently provides a divorce clause to dispose of her (when she is no longer sexually gratifying) without providing her food or shelter or returning her to her family. . . . In this way, the foreign captive is divorced not for objectionable actions like other (Israelite/Hebrew) wives but for reasons beyond her control."[28]

David Resnick praises the passage for its nobility, calling it "evidently the first legislation in human history to protect women prisoners of war" and "the best of universalist Biblical humanism as it seeks to manage a worst case scenario: controlling how a conquering male must act towards a desired, conquered, female other." He argues that after the defeat of her nation in war, marrying the victors "may be the best way for a woman to advance her own interests in a calamitous political and social situation."[29] By treating her as a wife, rather than as a slave, the law seeks to compensate for the soldier's having "violated her" by his failure to procure her father's approval, which was precluded by the state of war.[30]

Deuteronomy 22

Deuteronomy 22:22 states:

If a man be found lying with a woman married to an husband, then they shall both of them die, both the man that lay with the woman, and the woman: so shalt thou put away evil from Israel.

This passage does not specifically address the wife's complicity, and therefore one interpretation is that even if she was raped, she must be put to death since she has been defiled by the extramarital encounter.[30]

Deuteronomy 22:25-27 states:

But if a man find a betrothed damsel in the field, and the man force her, and lie with her: then the man only that lay with her shall die. But unto the damsel thou shalt do nothing; there is in the damsel no sin worthy of death: for as when a man riseth against his neighbour, and slayeth him, even so is this matter: For he found her in the field, and the betrothed damsel cried, and there was none to save her.

- "If a man is caught in the act of raping a young woman who is not engaged, he must pay fifty pieces of silver to her father. Then he must marry the young woman because he violated her, and he will never be allowed to divorce her."

Tarico was critical of Deuteronomy 22:28-29, saying that "The punishments for rape have to do not with compassion or trauma to the woman herself but with honor, tribal purity, and a sense that a used woman is damaged goods."[31]

Cheryl Anderson, in her book Ancient Laws and Contemporary Controversies: The Need for Inclusive Bible Interpretation, discusses an anecdote about a student, who, when exposed to the passages in Deuteronomy, said that "This is the word of God. If it says slavery is okay, slavery is okay. If it says rape is okay, rape is okay."[32] Elaborating on this, she states in response to these passages, "Clearly, these laws do not take into account the female's perspective. After a rape, [the victim] would undoubtedly see herself as the injured party and would probably find marriage to her rapist to be distasteful, to say the least. Arguably, there are cultural and historical reasons why such a law made sense at the time. […] Just the same, the law communicates the message that faith tradition does not (and should not) consider the possibility that women might have different yet valid perspectives."[33]

Richard M. Davidson regarded Deuteronomy 22:28-29 as a law concerning statutory rape. He argued that the laws do support the role of women in the situation, writing, "even though the woman apparently consents to engage in sexual intercourse with the man in these situations, the man nonetheless has 'afflicted/humbled/violated her'. The Edenic divine design that a woman's purity be respected and protected has been violated. […] Even though the woman may have acquiesced to her seducer, nonetheless according to the law, the dowry is 'equal to the bride wealth for virgins' (Exodus 22:16): she is treated financially as a virgin would be! Such treatment upholds the value of a woman against a man taking unfair advantage of her, and at the same time discourages sexual abuse."[34] Regarding 22:25-27, Craig S. Keener noted that "biblical law assumes [the woman's] innocence without requiring witnesses; she does not bear the burden of proof to argue that she did not consent. If the woman might have been innocent, her innocence must be assumed,"[35] while Davidson added, "Thus the Mosaic law protects the sexual purity of a betrothed woman (and protects the one to whom she is betrothed), and prescribing the severest penalty to the man who dares to sexually violate her."

Robert S. Kawashima notes that regardless of whether the rape of a girl occurs in the country or the city, she "can be guilty of a crime, but not, technically speaking, a victim of a crime, for which reason her noncomplicity does not add to the perpetrator's guilt."[30]

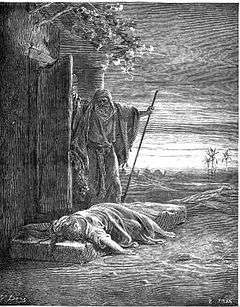

Judges

Trible devotes a chapter in Texts of Terror to the rape of the concubine in the Book of Judges, titled "An Unnamed Woman: The Extravagance of Violence". About the rape of the concubine itself, she wrote, "The crime itself receives few words. If the storyteller advocates neither pornography or sensationalism, he also cares little about the women's fate. The brevity of this section on female rape contrasts sharply with the lengthy reports on male carousing and male deliberations that precede it. Such elaborate attention to men intensifies the terror perpetrated upon the woman."[36] After noting that differences in the Greek and Hebrew versions of the Bible make it unclear whether or not the concubine was dead the following morning ("the narrator protects his protagonist through ambiguity"),[37] Trible writes that "Neither the other characters nor the narrator recognizes her humanity. She is property, object, tool, and literary device. [..] In the end, she is no more than the oxen that Saul will later cut in pieces and send throughout all the territory of Israel as a call to war."[38]

Scholz notes the linguistic ambiguity of the passage and the variety of interpretations that stem from it. She wrote that "since this narrative is not a 'historical' or 'accurate' report about actual events, the answers to these questions reveal more about a reader's assumptions regarding gender, androcentrism, and sociopolitical practices than can be known about ancient Israelite life based on Judges 19. […] Predictably, interpreters deal differently with the meaning of the story, depending on their hermeneutical interests."[39]

Yamada believes that the language used to describe the plight of the concubine make the reader sympathize with her, especially during the rape and its aftermath. "Thus, the narrator's elaborate description of the woman's attempt to return to the old man's house highlights for the reader the devastating effects of the preceding night's events, emphasizing her desolate state. The woman's raped and exhausted body becomes a symbol of the wrong that is committed when 'every man did what was right in his own eyes.' The image of this woman struggling to the door demands a response from the participants in the story."[40]

2 Samuel

2 Samuel 11

Some scholars see the episode of David's adultery with Bathsheba in 2 Samuel 11 as an account of a rape. David and Diana Garland suggest that:

Since consent was impossible, given her powerless position, David in essence raped her. Rape means to have sex against the will, without the consent, of another – and she did not have the power to consent. Even if there was no physical struggle, even if she gave in to him, it was rape.[41]

Other scholars, however, suggest that Bathsheba came to David willingly. James B. Jordan notes that the text does not describe Bathsheba's protest, as it does Tamar's in 2 Samuel 13, and argues that this silence indicates that "Bathsheba willingly cooperated with David in adultery."[42] George Nicol goes even further and suggests that "Bathsheba's action of bathing in such close proximity to the royal palace was deliberately provocative."[43]

2 Samuel 13

In 2 Samuel 13, Tamar asks her half-brother Amnon not to rape her, saying, "I pray thee, speak unto the king; for he will not withhold me from thee." Kawashima notes that "one might interpret her remarkably articulate response as mere rhetoric, an attempt to forestall the impending assault, but the principle of verisimilitude still suggests that David, as patriarch of the house, is the legal entity who matters" when it comes to consenting to his daughter's union with Amnon. When, after the rape, Amnon tells Tamar to leave, she says, "There is no cause: this evil in sending me away is greater than the other that thou didst unto me", indicating her expectation, in accordance with the conventions of the time, is to remain in his house as his wife.[30]

In The Cry of Tamar: Violence Against Women and the Church's Response, Pamela Cooper-White criticizes the Bible's depiction of Tamar for its emphasis on the male roles in the story and the perceived lack of sympathy given to Tamar. "The narrator of 2 Samuel 13 at times portrays poignantly, eliciting our sympathy for the female victim. But mostly, the narrator (I assume he) steers us in the direction of primary interest, even sympathy, for the men all around her. Even the poignancy of Tamar's humiliation is drawn out for the primary purpose of justifying Absalom's later murder of Amnon and not for its own sake."[44] She opined that "Sympathy for Tamar is not the narrator's primary interest. The forcefulness of Tamar's impression is drawn out, not to illuminate her pain, but to justify Absalom's anger at Amnon and subsequent murder of him."[45] Cooper-White also states that after the incestuous rape, the narrative continues to focus on Amnon, writing, "The story continues to report the perpetrator's viewpoint, the thoughts and feelings after the incident of violence; the victim's viewpoint is not presented. […] We are given no indication that he ever thought about her again—even in terms of fear of punishment or reprisal."[46]

Trible allocates another chapter in Texts of Terror to Tamar, subtitled "The Royal Rape of Wisdom." She noted that Tamar is the lone female in the narrative and is treated as part of the stories of Amnon and Absalom. "Two males surround a female. As the story unfolds, they move between protecting and polluting, supporting and seducing, comforting and capturing her. Further, these sons of David compete with each other through the beautiful woman."[47] She also wrote that the language the original Hebrew uses to describe the rape is better translated as "He laid her" than "He lay with her."[48] Scholz wrote that "Many scholars make a point of rejecting the brutality with which Amnon subdues his [half-]sister," going on to criticize an interpretation by Pamela Tamarkin Reis that blames Tamar, rather than Amnon, for what happened to her.[49]

Regarding the rape of Tamar in 2 Samuel, Rapoport states that "Amnon is an unmitigatedly detestable figure. Literarily, he is the evil foil to Tamar's courageous innocence. […] The Bible wants the reader to simultaneously appreciate, mourn, and cheer for Tamar as we revile and despise Amnon."[50] Regarding the same passage, Bader wrote that "Tamar's perception of the situation is given credibility; indeed Amnon's lying with her proved to be violating her. Simultaneously with increasing Tamar's credibility, the narrator discredits Amnon."[51] Trible opined that "[Tamar's] words are honest and poignant; they acknowledge female servitude."[52] She also writes that "the narrator hints at her powerlessness by avoiding her name."[48]

Similarly, Yamada argues that the narrator aligns with Tamar and makes the reader sympathize with her. "The combination of Tamar's pleas with Amnon's hatred of his half-sister after the violation aligns the reader with the victim and produce scorn toward the perpetrator. The detailed narration of the rape and post-rape responses of the two characters makes this crime more deplorable."[53]

Prophetic books

Both Kate Blanchard[4] and Scholz note that there are several passages in the Book of Isaiah, Book of Jeremiah, and Book of Ezekiel that utilize rape metaphors.[54] Blanchard expressed outrage over this fact, writing "The translations of these shining examples of victim-blaming are clear enough, despite the old-fashioned language: I'm angry and you're going to suffer for it. You deserve to be raped because of your sexual exploits. You're a slut and it was just a matter of time till you suffered the consequences. Let this be a lesson to you and to all other uppity women."[4] Scholz discussed four passages—Isaiah 3:16-17, Jeremiah 13:22 and 26, Ezekiel 16, and Ezekiel 23.[55] On Isaiah, Scholz wrote that there is a common mistranslation of the Hebrew word pōt as "forehead" or "scalp". Also often translated as "genitals", Scholz believes that a more accurate translation of the word in context is "cunt".[56] Regarding Jeremiah, Scholz wrote, "The poem proclaims that the woman brought this fate upon herself and she is to be blamed for it, while the prophet sides with the sexually violent perpetrators, viewing the attack as deserved and God as justifying it. Rape poetics endorses 'masculine authoritarianism' and the 'dehumanization of women,' perhaps especially when the subject is God."[57]

Scholz refers to both passages in Ezekiel as "pornographic objectification of Jerusalem."[58] On Ezekiel 16, she wrote, "These violent words obscure the perspective of the woman, and the accusations are presented solely through the eyes of the accuser, Yahweh. God speaks, accuses his wife of adultery, and prescribes the punishment in the form of public stripping, violation, and killing. In the prophetic imagination, the woman is not given an opportunity to reply. […] God expresses satisfaction of her being thus punished."[58] Regarding Ezekiel 23, a story about two adulterous sisters who are eventually killed, she decries the language used in the passage, especially Ezekiel 23:48, which serves as a warning to all women about adultery. "The prophetic rape metaphor turns the tortured, raped, and murdered wives into a warning sign for all women. It teaches that women better obey their husbands, stay in their houses, and forgo any signs of sexual independence. […] This prophetic fantasy constructs women as objects, never as subjects, and it reduces women to sexualized objects who bring God's punishment upon themselves and fully deserve it.[59] Amy Kalmanofsky opined that Jeremiah 13 treats the naked female body as an object of disgust: "I conclude that Jer 13 is an example of obscene nudity in which the naked female body is displayed not as an object of desire, but of disgust. In Jer 13, as in the other prophetic texts, Israel is not sexually excited by having her nakedness exposed. She is shamed. Moreover, those who witness Israel's shame do not desire Israel's exposed body. They are disgusted by it."[60]

Conversely, Corrine Patton argued that "this text does not support domestic abuse; and scholars, teachers, and preachers must continue to remind uninformed readers that such an interpretation is actually a misreading" and that "the theological aim of the passage is to save Yahweh from the scandal of being a cuckolded husband, i.e. a defeated, powerless, and ineffective god. […] It is a view of God for whom no experience, not even rape and mutilation in wartime, is beyond hope for healing and redemption."[61] Regarding Ezekiel 16, Daniel I. Block wrote that "the backdrop of divine judgment can be appreciated only against the backdrop of his grace. If the text had begun at v. 36 one might understandably had accused God of cruelty and undue severity. But the zeal of his anger is a reflex of the intensity of his love. God had poured out his love on this woman, rescuing her from certain death, entering into covenant relationship with her, pledging his troth, lavishing on her all the benefits she could enjoy. He had loved intensely. He could not take contempt for his grace lightly."[62] F. B. Huey, Jr., commenting on Jeremiah, wrote, "The crude description is that of the public humiliation inflicted on a harlot, an appropriate figure for faithless Judah. It could also describe the violence done to women by soldiers of a conquering army. […] Jeremiah reminded [Israel] that they were going to be exposed for all to see their adulteries."[63]

See also

- Marry-your-rapist law#Antiquity until 1900

- Susanna, a biblical figure subjected to sexual harassment

References

- Yamada (2008), p. 22

- Deuteronomy 22:23-29

- Yamada (2008), pp. 22-24

- Gafney, Wil (January 15, 2013). "God, the Bible, and Rape". The Huffington Post. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- Trible (1984), p. 5

- Genesis 34:2

- Rapoport (2011), page 94

- Numbers 31:15-18

- Title = Power and Marginality in the Abraham Narrative (Second Edition) | Author = Hemchand Gossai | Pub = Pickwick Publications | pg = 79

- Judges 19:22-26

- Trible (1984), pp. 37-38

- 2 Samuel 13:1-14

- Elliot Freeman, Richard; Dolansky, Shawna (2011). The Bible Now. Oxford University Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-19-531163-1. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- Fuchs, Esther (2003). Sexual Politics in the Biblical Narrative: Reading the Hebrew Bible as a Woman. p. 209. ISBN 9780567042873. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- Lerner, Gerda (1986). The Creation of Patriarchy. Oxford University Press. p. 173. ISBN 9780195051858.

- Genesis 34:7

- Rapoport, pp. 103-104

- Rapoport, p. 104

- Scholz (2000), pp. 168-169

- Scholz (2010), pp. 32-33

- Gruber, Mayer I. (1999). "A Re-examination of the Charges against Shechem son of Hamor". Beit Mikra (in Hebrew) (157): 119–127.

- Bader (2006), p. 91

- Bader (2006), p. 92

- Rapoport (2011), pp. 127-128

- Scholz (2000), p. 168

- Yamada (2008), p. 45

- Reeder, Caryn A (March 2017). "Deuteronomy 21.10–14 and/as Wartime Rape". Journal for the Study of the Old Testament. 41 (3): 313–336. doi:10.1177/0309089216661171.

- Rey (2016). "Reexamination of the Foreign Female Captive: Deuteronomy 21:10–14 as a Case of Genocidal Rape". Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion. 32 (1): 37–53. doi:10.2979/jfemistudreli.32.1.04.

- Resnick, David (1 September 2004). "A case study in Jewish moral education: (non‐)rape of the beautiful captive". Journal of Moral Education. 33 (3): 307–319. doi:10.1080/0305724042000733073.

- Kawashima, Robert S (2011). "Could a Woman Say "No" in Biblical Israel? On the Genealogy of Legal Status in Biblical Law and Literature". AJS Review. 35 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1017/S0364009411000055.

- Tarico, Valerie (November 1, 2012). "What the Bible Says about Rape". AlterNet. Retrieved May 12, 2015.

- Anderson (2009), p. 3

- Anderson (2009), p. 3-4

- Davidson, Richard M. (2011). "Sexual Abuse in the Old Testament: An Overview of Laws, Narratives, and Oracles". In Schmutzer, Andrew J. (ed.). The Long Journey Home: Understanding and Ministering to the Sexually Abused. p. 136. ISBN 9781621893271. Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- Keener, Craig S. (1996). "Some Biblical Reflections on Justice, Rape, and an Insensitive Society". In Kroeger, Catherine Clark; Beck, James R. (eds.). Women, Abuse, and the Bible: How Scripture Can be Used to Hurt or to Heal. p. 126.

- Trible (1984), p. 56

- Trible (1984), pp. 59-60

- Trible (1984), p. 61

- Scholz (2010), pp. 139-144

- Yamada (2008), p. 90

- Garland, David E.; Garland, Diana R. "Bathsheba's Story: Surviving Abuse and Loss" (PDF). Baylor University. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- Jordan, James B. (1997). "Bathsheba: The Real Story". Biblical Horizons. 93. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- Nicol, George G. (1997). "The Alleged Rape of Bathsheba: Some Observations on Ambiguity in Biblical Narrative". Journal for the Study of the Old Testament. 73: 44.

- Cooper-White (1995), p. 29

- Cooper-White (1995), p. 30

- Cooper-White (1995), p. 31

- Trible (1984), p. 26

- Trible (1984), p. 34

- Scholz (2010), p. 39

- Rapoport (2011), p. 352

- Bader (2006), p. 147

- Trible (1984), p. 33

- Yamada (2008), p. 114

- Scholz (2010), p. 181

- Scholz (2010), p. 182

- Scholz (2010), p. 182-183

- Scholz (2010), p. 184

- Scholz (2010), p. 188

- Scholz (2010), p. 191

- Kalmanofsky, Amy (2015). "Bare Naked: A Gender Analysis of the Naked Body in Jeremiah 13". In Holt, Else K.; Sharp, Carolyn J. (eds.). Jeremiah Invented: Constructions and Deconstructions of Jeremiah. p. 62. ISBN 9780567259172.

- Patton, Corrine (2000). ""Should Our Sister Be Treated Like a Whore"? A Response to Feminist Critiques of Ezekiel 23". In Odell, Margaret S.; Strong, John T. (eds.). The Book of Ezekiel: Theological and Anthropological Perspectives. Atlanta, GA: Society of Biblical Literature. p. 238. OCLC 44794865.

- Block, Daniel I. (1997). The Book of Ezekiel, Chapters 1-24. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 498.

- Huey, Jr., F.B. (1993). Lamentations, Jeremiah: An Exegetical and Theological Exposition of Holy Scripture. Nashville, Tennessee: Lifeway Christian Resources. pp. 149–150. ISBN 9781433675584.

- Works cited

- Trible, Phyllis (1984). Texts of Terror: Literary-Feminist Readings of Biblical Narratives. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press. pp. 37–64. ISBN 978-0-8006-1537-6. Retrieved May 12, 2015.

- Anderson, Cheryl (2009). Ancient Laws and Contemporary Controversies: The Need for Inclusive Bible Interpretation. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0195305500. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- Rapoport, Sandra (2011). Biblical Seductions: Six Stories Retold Based on Talmud and Midrash. Jersey City, NJ: KTAV Publishing House. ISBN 978-1-60280-154-7.

- Bader, Mary Anna (2006). Sexual Violation in the Hebrew Bible: A Multi-Methodological Study of Genesis 34 and 2 Samuel 13. New York: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-0-8204-7873-9.

- Cooper-White, Pamela (2012) [1995]. The Cry of Tamar: Violence Against Women and the Church's Response (2nd ed.). Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press. ISBN 978-0-8006-9734-1. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

- Scholz, Susanne (2000). Rape Plots: A Feminist Cultural Study of Genesis 34. New York: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-0-8204-4154-2. Retrieved June 2, 2015.

- Yamada, Frank M. (2008). Configurations of Rape in the Hebrew Bible: A Literary Analysis of Three Rape Narratives. New York: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-1433101670. ASIN 143310167X.

- Scholz, Susanne (2010). Sacred Witness: Rape in the Hebrew Bible. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press. ISBN 978-0800638610.