Tambopata National Reserve

Tambopata National Reserve (Spanish: Reserva Nacional Tambopata) is a Peruvian nature reserve located in the southeastern region of Madre de Dios. It was established on September 4, 2000, by decree of President Alberto Fujimori.[1] The reserve protects several ecosystems of the tropical rainforest for the preservation of such forest and the sustainable use of forest resources by the peoples around the reserve.[2]

| Tambopata National Reserve | |

|---|---|

IUCN category VI (protected area with sustainable use of natural resources) | |

Shores of Lake Sandoval, inside Tambopata National Reserve. | |

| |

| Location | Tambopata Province, Madre de Dios |

| Nearest city | Puerto Maldonado |

| Coordinates | 12°55′14″S 69°16′55″W |

| Area | 274,690 hectares (1,060.6 sq mi) |

| Established | 4 September 2000 |

| Governing body | SERNANP |

| Website | Reserva Nacional Tambopata (in Spanish) |

Geography

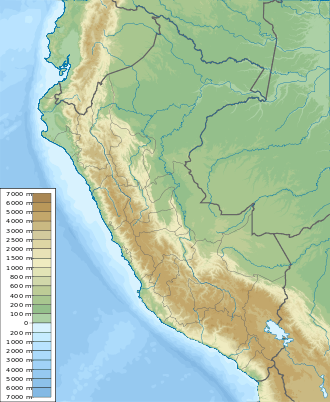

Tambopata National Reserve is located south of the Madre de Dios river, in the province of Tambopata, region of Madre de Dios.[2] It reaches the border with Bolivia to the east and borders with Bahuaja Sonene National Park to the south.[2]

The area consists of forested hills and plains, with elevations ranging from 200 to 400 m above sea level.[3] The area presents swamps, oxbow lakes and meandering rivers; the main rivers in the reserve being the Tambopata, Malinowski and Heath rivers.[3]

Climate

The annual mean temperature in the area is 26 °C, with a range between 10° and 38 °C.[2] The lower temperatures are caused by cold winds of antarctic origin; these cold waves occur in June and July.[2] The rainy season occurs between December and March.[2]

Ecology

Tambopata National Reserve protects an area of rainforest,[2] which belongs to the moist and wet subtropical forest according to the Holdridge life zone classification.[3] The reserve is of ecological importance as it is part of the Vilcabamba Amboro wildlife corridor, which extends into neighboring Bolivia.[2][3]

Flora

Vascular plants are represented in the reserve by 1713 species in 145 families.[3] Among the species found in this protected area are: Virola surinamensis, Cedrela odorata, Oncidium spp., Bertholletia excelsa, Geonoma deversa, Minquartia guianensis, Epidendrum coronatum, Iriartea deltoidea, Celtis schippii, Spondias mombin, Mauritia flexuosa, Cedrelinga cateniformis, Hymenaea courbaril, Ficus trigonata, Croton draconoides, Inga spp., Attalea tessmannii, Calycophyllum spruceanum, Swietenia macrophylla, Dipteryx charapilla, Couroupita guianensis, Socratea exorrhiza, Hura crepitans, Manilkara bidentata, Clarisia racemosa, Hevea guianensis, Guadua weberbaueri, Ceiba pentandra, etc.[3][4]

Fauna

Among the mammal species found in the reserve are: the jaguar, the puma, the ocelot, the collared peccary, the giant otter, the Peruvian spider monkey, the jaguarundi, Hoffmann's two-toed sloth, the capybara, the tufted capuchin, the white-lipped peccary, the marsh deer, the red brocket, the brown-throated sloth, the black-capped squirrel monkey, the South American tapir, etc.[2]

Some of the species of fish present in the reserve are: Prochilodus nigricans, Potamorhina latior, Brachyplatystoma flavicans, Piaractus brachypomus, Brycon spp., Schizodon fasciatus, etc.[2]

Some species of birds present in the reserve are: the harpy eagle, the white-necked jacobin, the scarlet macaw, the rufescent tiger heron, the king vulture, the roseate spoonbill, the crested eagle, the razor-billed curassow, the blue-and-yellow macaw, the variegated tinamou, the sunbittern, the red-and-green macaw, the horned curassow, the golden-tailed sapphire, etc.[2][5]

Silkhenge mystery

In 2013, Georgia Tech researcher Troy Alexander discovered four bizarre gazebo-shaped spider nests while visiting the Reserve. The nests, which have since come to be known as Silkhenge structures, were each composed of an undocumented silk compound and consisted of a circular fence-like formation encompassing a spire at its center. Alexander's subsequent Reddit inquiry was unable to identify the peculiar nest structure pictured or the species of arthropod associated with it.

Later that year, an expedition to the Reserve led by Phil Torres observed 45 additional like structures.[6] While the team successfully documented several spiderlings hatching from the nests (video of which was later posted online), none of them survived into adulthood. Furthermore, the team was unable to observe any member of the species to exhibit the characteristics indicative of adult arthropods. With DNA testing proving inconclusive, the species native to Silkhenge structures remains unidentified.[7]

Anthropology

The Ese Ejja and Pukirieri Huachipaeri native peoples inhabit the buffer zone surrounding the reserve.[2]

Recreation

The main recreational activities in the reserve are wildlife observation and camping, as there are several spots furnished for those purposes.[2] Lake Sandoval, 30 minutes from Puerto Maldonado, is the most visited place in the reserve, its shores covered with palm trees which are home to macaws, can be toured by boat.[2] Two other lakes can be reached after 2 and 3 hour trips, respectively.[2] There are also many mineral licks where birds and mammals gather and are popular nature watching spots.[2]

Access

The reserve can be reached by boat from the town of Puerto Maldonado.[2]

Environmental issues

Illegal gold mining is the main threat to the environment in the reserve.[8] This activity has destroyed more than 450 hectares of forest inside the area.[8]

References

- "Reserva Nacional Tambopata | Legislación". legislacionanp.org.pe (in Spanish). Retrieved 2018-10-23.

- "Tambopata - Servicio Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas por el Estado". www.sernanp.gob.pe (in Spanish). Retrieved 2018-10-23.

- Diagnostico del Proceso de Elaboracion del Plan Maestro 2011-2016 (in Spanish). SERNANP. 2012. ISBN 978-612-46157-4-0.

- Perez, Fernando (2008). Caracterización ecológica de la variación de la vegetación de un aguajal en la Reserva Nacional Tambopata, Madre de Dios. (Thesis) (in Spanish). Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina. pp. 8–9, 49–51.

- The Tambopata-Candamo reserved zone of southeastern Perú: a biological assessment. Conservation International. 1994. pp. 106–124.

- WE WENT TO THE AMAZON TO FIND OUT WHAT MAKES THESE WEIRD WEB-TOWER THINGS

- Mysterious 'Silkhenge spider' is a master architect

- "Gold mining deforestation in Peruvian reserve surpasses 450 hectares". Mongabay Environmental News. 2016-10-13. Retrieved 2018-10-27.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tambopata National Reserve. |