Taoudenni

Taoudenni (also Taoudeni, Taoudénit, Taudeni, Berber languages: Tawdenni) is a remote salt mining center in the desert region of northern Mali, 664 km (413 mi) north of Timbuktu. It is the capital of Taoudénit Region.[1] The salt is dug by hand from the bed of an ancient salt lake, cut into slabs, and transported either by truck or by camel to Timbuktu. The camel caravans (azalai) from Taoudenni are some of the last that still operate in the Sahara Desert. In the late 1960s, during the regime of Moussa Traoré, a prison was built at the site and the inmates forced to work in the mines. The prison was closed in 1988.

Taoudenni Tawdenni | |

|---|---|

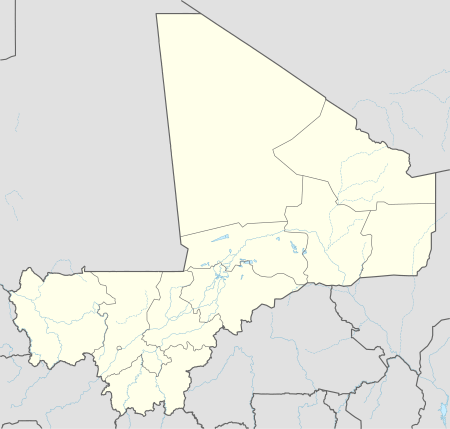

Taoudenni Location within Mali | |

| Coordinates: 22°40′N 3°59′W | |

| Country | |

| Region | Taoudénit |

| Time zone | UTC+0 (GMT) |

Salt mining

The earliest mention of Taoudenni is by al-Sadi, in his Tarikh al-Sudan, who wrote that in 1586 when Moroccan forces attacked the salt mining center of Taghaza (150 km north west of Taoudenni) some of the miners moved to 'Tawdani'.[2] In 1906 the French soldier Édouard Cortier visited Taoudenni with a unit of the camel corps (méharistes) and published the first description of the mines.[3] At the time the only building was the Ksar de Smida, which had a surrounding wall with a single small entrance on the western side. The ruins of the ksar are 600 m north of the prison building.[4]

The Taoudenni mines are located on the bed of an ancient salt lake. The miners use crude axes to dig pits, which usually measure 5 m by 5 m with a depth of 4 m. The miners first remove 1.5 m of red clay overburden, then several layers of poor quality salt before reaching three layers of high quality salt. The salt is cut into irregular slabs that are around 110 cm x 45 cm by 5 cm in thickness and weigh around 30 kg. Two of the high quality layers are of sufficient thickness to be split in half, so that 5 slabs can be produced from the three layers. Having removed the salt from the base area of the pit, the miners excavate horizontally to create galleries from which additional slabs can be obtained.[5]

As each pit is exhausted another is dug, so there are now thousands of pits spread over a wide area. Over the centuries salt has been extracted from three distinct areas of the depression, with each successive area located further to the south west. The three areas can be seen clearly on satellite photographs. At the time of Édouard Cortier's visit in 1906 the mining area was 3 km south of the ksar;[6] in the 1950s the active mines were located in an area 5 km from the ksar,[7] while the current mines are at a distance of 9 km.[8]

In 2007-2008 there were around 350 teams of miners, with each team usually consisting of an experienced miner with 2 labourers, giving a total of around 1000 men. The men live in primitive huts constructed from blocks of inferior quality salt and work at the mines from October to April, avoiding the hottest months of the year, when only about 10 of them remain.[9]

The slabs are transported across the desert via the oasis of Araouane to Timbuktu. In the past they were always carried by camel, but recently some of the salt has been moved by four-wheel drive trucks.[10] By camel the journey to Timbuktu takes around three weeks, with each camel carrying either four or five slabs. The typical arrangement is that for each four slabs transported to Timbuktu, one is for the miners and the other three are payment for the camel owners.[11]

Up to the middle of the 20th century the salt was transported in two large camel caravans (azalaï), one leaving Timbuktu in early November and a second leaving Timbuktu in late March, at the end of the season.[12] Horace Miner, an American anthropologist who spent seven months in the town, estimated that in 1939-40 the winter caravan consisted of more than 4,000 camels and that the total production amounted to 35,000 slabs of salt.[13] Jean Clauzel records that the number of slabs reaching Timbuktu increased from 10,515 in 1926 to 160,000 (4800 t) in 1957-1958.[14] However, in the early 1970s the production decreased, and at the end of the decade was between 50,000 and 70,000 slabs.[15]

Prison

A military post and a prison were built at Taoudenni in 1969 during the regime of Moussa Traoré.[16] The prison was used to detain political prisoners until 1988, when it was closed.[17] Many of the prisoners were government officials who had been accused of plotting against the regime.[18] The prisoners worked in the salt mines and many of them died. To the east of the ruins of the prison building is a cemetery containing 140 individual graves, of which only a dozen have names. They include:[19]

- Yoro Diakité, head of the first provisional government following the coup of 19 November 1968, who died in 1973.

- Tiécoro Bagayoko, head of security services from 1968 to 1978, who died in August 1983.

- Kissima Doukara, Minister of Defence 1968-1978.

- Youssouf Balla Sylla, police chief of the 3rd Arrondissement of Bamako.

- Jean Bolon Samaké, head of the Goundam Cercle in 1969, who died in 1973.

Climate

Taoudenni is a remote site in the hottest region on the planet, located over a hundred and sixty kilometres from the nearest inhabited location of any size. The region is located in the middle of the Sahara Desert, in the southern part of the Tanezrouft (one of the harshest areas on the planet, known for extreme heat and aridity), and features an extreme version of the hot desert climate (Köppen climate classification BWh). The region features a torrid, hyper-arid climate with unbroken sunshine all year-long. Averages high temperatures exceed 40℃ (104℉) from April to September and reach an extreme peak of 48℃ (118.2℉) in July, the highest value for such an elevation above sea level.[20] Winters are also very warm compared to the world average. High temperatures average close to 27℃ (80.6℉) in the coolest month. The mean annual daily temperature is around 29℃ (84.2℉), among the highest in the world. The annual average rainfall is between 10 mm (0.39 in) and 20 mm (0.78 in) which mainly falls from July to October.[21] On average, Taoudenni sees 3,700 hours of bright sunshine annually, with 84% of daytime hours being sunny. The site is also located in one of the driest regions on the globe.[22]

| Climate data for Taoudenni | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 26.2 (79.2) |

30 (86) |

32.5 (90.5) |

39.8 (103.6) |

42.6 (108.7) |

46.7 (116.1) |

47.9 (118.2) |

46.6 (115.9) |

44.1 (111.4) |

38.6 (101.5) |

31.6 (88.9) |

26.4 (79.5) |

37.8 (100.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 18.1 (64.6) |

21.1 (70.0) |

24.4 (75.9) |

29.8 (85.6) |

33.1 (91.6) |

37.2 (99.0) |

38.8 (101.8) |

37.8 (100.0) |

35.9 (96.6) |

30.4 (86.7) |

23.9 (75.0) |

18.6 (65.5) |

28.2 (82.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 9.9 (49.8) |

12.2 (54.0) |

16.3 (61.3) |

19.8 (67.6) |

23.6 (74.5) |

27.6 (81.7) |

29.6 (85.3) |

29 (84) |

27.6 (81.7) |

22.1 (71.8) |

16.2 (61.2) |

10.8 (51.4) |

20.4 (68.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 0.5 (0.02) |

0.1 (0.00) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.01) |

0.2 (0.01) |

0.4 (0.02) |

3.0 (0.12) |

8.5 (0.33) |

5.4 (0.21) |

1.6 (0.06) |

0.5 (0.02) |

0.4 (0.02) |

20.8 (0.82) |

| Average precipitation days | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 33.5 | 29.1 | 25.6 | 23.1 | 23.5 | 28.9 | 35.8 | 43.0 | 40.4 | 31.4 | 32.3 | 34.2 | 31.7 |

| Source: Weatherbase[23] | |||||||||||||

See also

- Taoudeni basin

Notes

- "Mali : Taoudeni, contrée historique" (in French). 21 February 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- Hunwick 2003, p. 167.

- Cortier 1906, pp. 328-330.

- The ruins of the ksar are at 22°40′46″N 3°58′49″W. A plan of the ksar was published by Cortier in 1906, p. 327.

- Clauzel 1960, pp. 23-54.

- Cortier 1906, p. 328.

- Clauzel 1960.

- Papendieck, Papendieck & Schmidt 2007, p. 9. The actives mines in 2007 were located near 22°37′5″N 4°2′9″W.

- Papendieck, Papendieck & Schmidt 2007, p. 7.

- Harding, Andrew (3 Dec 2009), Timbuktu's ancient salt caravans under threat, BBC News, retrieved 6 Mar 2011.

- Clauzel 1960, p. 90.

- Miner 1953, p. 66 n27.

- Miner 1953, p. 68.

- Clauzel 1960, p. 89.

- Meunier 1980, p. 135.

- Papendieck, Papendieck & Schmidt 2007, p. 7, para 6.

- Minorities at Risk Project: Chronology for Tuareg in Mali, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 2004, retrieved 14 Mar 2011

- Sangaré 2011.

- Papendieck, Papendieck & Schmidt 2007, p. 9.

- contemporain, Centre pour l'étude des problèmes du monde musulman. "Correspondance d'Orient". Retrieved 12 September 2017 – via Google Books.

- "Climat Teghaza: Diagramme climatique, Courbe de température, Table climatique pour Teghaza - Climate-Data.org". fr.climate-data.org. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- "Holocene climatic evolution at 22–23°N from two palaeolakes in the Taoudenni area (Northern Mali)". ResearchGate. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- "Weatherbase". Retrieved 2015-06-19.

References

- Clauzel, Jean (1960), L'exploitation des salines de Taoudenni (in French), Alger: Université d'Alger, Institut de Recherches Sahariennes.

- Cortier, Édouard (1906), "De Tombouctou à Taodéni: Relation du raid accompli par la compagnie de méharistes du 2e Sénégalais commandée par le capitaine Cauvin. 28 février -17 juin 1906", La Géographie (in French), 14 (6): 317–341. A map showing the route from Timbuktu to Taoudenni is included here. The article is also available from the Internet Archive.

- Hunwick, John O. (2003), Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Sadi's Tarikh al-Sudan down to 1613 and other contemporary documents, Leiden: Brill, ISBN 90-04-12560-4. First published in 1999 as ISBN 90-04-11207-3.

- Meunier, D. (1980), "Le commerce du sel de Taoudeni", Journal des Africanistes (in French), 50 (2): 133–144, doi:10.3406/jafr.1980.2010.

- Miner, Horace (1953), The Primitive City of Timbuctoo, Princeton University Press. Link requires subscription to Aluka. Reissued by Anchor Books, New York in 1965.

- Papendieck, Barbara; Papendieck, Henner; Schmidt, Wieland (photographer) (2007), Logbuch einer Reise von Timbuktu nach Taoudeni 23.–28.12. 2007 (PDF) (in German), Mali-Nord. The text and pictures are available as a series of 13 web pages. There is a series of 219 photographs by Wieland Schmidt. The photographs do not have captions.

- Sangaré, Samba Gaïné (14 February 2011), Témoignage: Dans l'enfer de Taoudénit (in French), DiasporAction, archived from the original on 15 February 2013, retrieved 3 February 2013. An interview with Samba Gaïné Sangaré.

Further reading

- Cauvin, Charles; Cortier, Édouard; Laperrine, Henri (1999), La pénétration saharienne: 1906, le rendez-vous de Taodéni (in French), Harmattan, ISBN 2-7384-7927-8. Pages 37–66 are a reprint of the 1906 article by Cortier.

- Despois, Jean (1962), "Les salines de Taoudenni", Annales de Géographie (in French), 71 (384): 220. A one-page summary of Clauzel (1960).

- McDougall, E. Ann (1990), "Salts of the Western Sahara: myths, mysteries, and historical significance", International Journal of African Historical Studies, 23 (2): 231–257, JSTOR 219336.

- Sangaré, Samba Gaïné (2001), Dix ans au bagne-mouroir de Taoudénit, Bamako: Librairie Traoré, OCLC 63274000.

- Skolle, John (1956), The Road to Timbuctoo, London: Gollancz, OCLC 640720603.

- Trench, Richard (1978), Forbidden Sands: A Search in the Sahara, London: J. Murray, ISBN 0-89733-027-7.