Ta'zieh

Ta'zieh or Ta'zïye or Ta'zīya or Tazīa or Ta'ziyeh, (Arabic: تعزية, Persian: تعزیه, Urdu: تعزیہ) means comfort, condolence or expression of grief. It comes from roots aza (عزو and عزى) which means mourning.

Depending on the region, time, occasion, religion, etc. the word can signify different cultural meanings and practices:

- In Persian cultural reference it is categorized as Condolence Theater or Passion Play inspired by a historical and religious event, the tragic death of Hussein, symbolizing epic spirit and resistance.

- In South Asia and in the Caribbean it refers specifically to the Miniature Mausoleums (imitations of the mausolems of Karbala, generally made of coloured paper and bamboo) used in ritual processions held in the month of Muharram.

Ta'zieh, primarily known from the Persian tradition, is a shi'ite Muslim ritual that reenacts the death of Hussein (the prophet Muhammad's grandson) and his male children and companions in a brutal massacre on the plains of Karbala, Iraq in the year 680 A.D. His death was the result of a power struggle in the decision of control of the Muslim community (called the caliph) after the death of the Prophet Muhammad.[1]

Today, we know of 250 Ta'zieh pieces. They were collected by an Italian ambassador to Iran, Cherulli, and added to a collection which can be found in the Vatican Library. Various other scripts can be found scattered throughout Iran.[2]

The Origins of Ta'zieh

Ta'zieh as a kind of passion play is a kind of comprehensive indigenous form considered as being the national form of Iranian theatre which have pervasive influence in the Iranian works of drama and play. It originates from some famous mythologies and rites such as Mithraism, Sug-e-Siavush (Mourning for Siavush) and Yadegar-e-Zariran or Memorial of Zarir.[3][4] The Ta'zieh tradition originated in Iran in the late 17th century.

There are two branches of Islam; the Sunni and the Shi'i. The Sunnis make up about 85-90% of Muslims, but the Ta'zieh tradition is performed by Shi'i Muslims during the first month of the Muslim calendar, Muharram, one of the four sacred months of the Islam calendar.[5] The Ta'Zieh is performed each year on the 10th day of Muharram, a historically significant day for the Shi'i Muslims because that was the day of Hussein's slaughter. Each year the same story is told, so the spectators know the story very well and know what to expect. However, this does not negatively affect audience levels.[6] In fact, the Ta'zieh welcomes large crowds and the audience members are known to cry each time the story is told in mourning and respect for Hussein.

A strong belief in the Muslim community was that nothing created by regular people could be better than the way Allah created it, so all other creation was deemed disrespectful. Because of this, there are not many accounts-visually or otherwise- of this religious tradition. During the tradition it was very important that all spectators knew the actors were not disrespecting Allah, so most often, the actors had their scripts on stage with them so it was clear that they were not trying to depict another person that Allah did not create.[5] The ritual was eventually banned by the authorities in Iran because the ritual was being exploited for political advances. Ta'zieh is not performed regularly in Iran and has not been seen at all in certain provinces of the region since 1920.[7] France was the first non-Muslim country that Ta'zieh was performed in 1991. Since then, the tradition has been seen in non-Persian cities like Avignon and Paris in France, Parma and Rome in Italy, and New York City.[8]

Ta'zieh in Persian Culture

| The ritual dramatic art of Ta'zīye | |

|---|---|

| Country | Iran |

| Reference | 377 |

| Region | Asia and Australasia |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 2010 |

In Persian culture it refers to condolence theater and Naqqali which are traditional Persian theatrical genres in which the drama is conveyed wholly or predominantly through music and singing. It dates from before the Islamic era and the tragedy of Saiawush in Shahnameh is one of the best examples.

In Persian tradition, Ta'zieh and Parde-khani, inspired by historical and religious events, symbolize epic spirit and resistance. The common themes are heroic tales of love and sacrifice and of resistance against the evil.

While in the West the two major genres of drama have been comedy and tragedy, in Persia, Ta'zieh seems to be the dominant genre. Considered as Persian opera, Ta'zieh resembles European opera in many respects.[9]

Persian cinema and Persian symphonic music have been influenced by the long tradition of Ta'zieh in Iran. Abbas Kiarostami, famous Iranian film maker, made a documentary movie titled "A Look to Ta'zieh" in which he explores the relationship of the audience to this theatrical form. Nasser Taghvaee also made a documentary on Ta'zieh titled "Tamrin e Akhar".

The appearance of the characteristic dramatic form of Persia known as the ta'zïye Mu'izz ad-Dawla, the king of Buyid dynasty, in 963. As soon as the Safavid Dynasty was established in Persia in 1501 and the Shiism of the Twelvers adopted as the official sect, the state took interest in theater as a tool of propagating Shiism.[10]

Women in Ta'Zieh

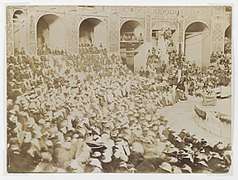

Women were not considered active members of the Ta'zieh performance ritual. Almost all women in these rituals were played by young males, however on some occasions little girls under the age of nine were able to fulfill small roles.[11] Women were traditionally played by males who would wear all black and veil their faces. During the festival period, the tekyehs were lavishly decorated by the women of the community that the performance took place, with the prized personal possessions of the local community. Refreshments were prepared by women and served to the spectators by the children of well-off families.[1] Society women were invited to watch the performance from the boxes above the general viewing area.[7] Generally the audience consisted of the more well-off families as they regarded Ta'zieh as entertainment, while the lower-class community members thought of it as an important religious ritual. The Ta'Zieh gained popularity during the 19th century and women painted scenes from Ta'Zieh performances on the stage on canvases and recorded history. This was a huge step in the history of islamic art.[12]

Importance of the Space

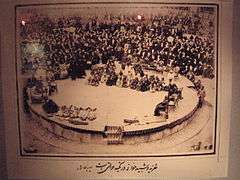

In Persian Ta'Zieh, the space is very important. Originally, Ta'zieh dramas, like other Western Passion Plays, were performed in a public arena, allowing large audiences to convene. They later moved to smaller spaces like courtyards and spaces within the homes of private citizens, but eventually ended up being performed in temporarily constructed performance spaces called tekyehs or husseiniyehs. The most famous tekyeh is called the Tekyeh Dowlat. It was built by the King of Persia, Naser al-Din Shah Qajar and was situated in the capital of Iran, Tehran. Tekyehs (with the exception of the Tekyeh Dowlat) were almost always constructed for temporary use and then demolished at the end of Muharram. The Tekyeh Dowlat was a permanent space built in 1868, but was torn down 79 years later in 1947 due to lack of use and replaced by a bank. Its capacity was 4,000.[13] They varied in size fitting anywhere between a dozen to thousands of spectators.[1] Tekyehs were somewhat open-air, but almost always had awnings of sorts atop the building to shield the spectators and actors from sun and rain. All performers in a Ta'Zieh ceremony never leave the stage. The stage is elevated between one and two feet from the ground and split into four areas: one for the protagonists, antagonists, smaller subplots, and props.[7]

Unlike most other theater traditions, especially Western theater traditions, the Ta'Zieh stage and its use of props were minimalist and stark. All tekyehs are designed so that the Ta'Zieh performance happens in-the-round to create a more intense experience between the actors and the audience.[14] This enabled spectators to feel like they were part of the action on stage and sometimes encouraged them to become physically active members of the performance.

Costumes and Character Distinctions

Costumes for a Ta'Zieh ritual are what is considered representational in terms of theater. They are not meant to present reality. The main goal of the costume design was not to be historically accurate, but to help the audience recognize which type of character they were looking at. Villains were the Sunni opponents of Imam Hussein. They are always dressed in red. The protagonists, family members of Hussein, were dressed in green if they were male characters.[2] Anyone about to die was in white. Women were always portrayed by men in all black.[1] One way to distinguish character besides the color of their costume is how they deliver their lines. The protagonists or family of Imam Hussein sing or chant their lines and the villains will declaim their lines. If a person is traveling in a circle on or around the stage, that meant they were going a long distance (usually represented the distance between Mecca and Karbala). Traveling in a straight line represented a shorter distance traveled.[2]

Animals in the Tradition

Often animals were used in the performance of a Ta'zieh. Often performers of Ta'zieh were on horseback. Most men from the time they were young would train to be able to ride a horse because it was an honor in Persian culture to be part of the Ta'zieh, especially to play a character who rode horseback. There were often other animals used in the tradition as well. These other animals were: camels, sheep or sometimes even a lion.[2] Usually the lion is not real, and is just represented by a man wearing a mask of some sort.

| A series of articles on |

| Husayn ibn Ali |

|---|

|

| Life |

|

| Remembrance |

|

| Perspectives |

Ta'zīya in South Asia

Shia Muslims take out a Ta'zīya (locally spelled Tazia, Tabut or Taboot) procession on day of Ashura in South Asia.[15]

The artwork is a colorfully painted bamboo and paper mausoleum. This ritual procession is also observed by south Asian Muslims throughout present-day India, Pakistan and Bangladesh as well as in countries with large historical South Asian diaspora communities established during the 19th century by indentured labourers to British, Dutch and French colonies. Notable regions outside of South Asia where such processions are performed include:

- British Guiana and Dutch Surinam ( now Guyana and Suriname)[16]

- Fiji[17]

- Trinidad and Tobago[18][19]

- Jamaica[20]

In the Caribbean it is known as Tadjah and was brought by Shia Muslim who arrived there as indentured labourers from the Indian subcontinent.

Tabuik made from bamboo, rattan and paper is a local manifestation of the Remembrance of Muharram among the Minangkabau people in the coastal regions of West Sumatra, Indonesia, particularly in the city of Pariaman culminates with practice of throwing a tabuik into the sea has taken place every year in Pariaman on the 10th of Muharram since 1831 when it was introduced to the region by Shia Muslim sepoy troops from India who were stationed and later settled there during the British Raj.[21]

During the colonial era in British India, the ta'zīya tradition was not only practiced by Shia Muslims and other Muslims but joined by Hindus.[22][23] Along with occasions for Shia Muslims and Hindus to participate in the procession together, the Tazia procession have also been historic occasions for communal conflicts between Sunni and Shia Muslims and between Hindu and Muslim communities since the 18th century, most notably the Muharram Rebellion which took place in Sylhet and was the first ever anti-British rebellion in the Indian subcontinent.[15][24] Also in the Sylhet region, a riot took place between the Muslim and Hindu communities, even though Sylhet's Faujdar Ganar Khan tried to prevent it from forming, due to Tazia coinciding with a Hindu chariot procession. These Tazia processions have traditionally walked through streets of a town, with mourning, flagellation and wailing, ultimately to a local lake, river or ocean where all the Tazia would be immersed into water.[15]

Tazia

|

| Part of a series on |

| Islamic culture |

|---|

| Architecture |

| Art |

|

| Dress |

| Holidays |

|

| Literature |

|

| Music |

| Theatre |

|

Like Western passion plays, ta'zia dramas were originally performed outdoors at crossroads and other public places where large audiences could gather. Much like in Iranian performances, these performances in other countries also began taking place in the courtyards of inns and private homes, but eventually unique structures called takias (referred to as tekyehs in Persian Ta'zieh) were constructed for the specific purpose of staging the plays. Community cooperation was encouraged in the building and decoration of the takias, whether the funds for the enterprise were provided by an individual philanthropist or by contributions from the residents of its particular locality. The takias varied in size, from intimate structures which could only accommodate a few dozen spectators to large buildings capable of holding an audience of more than a thousand people. All takias, regardless of their size and geographic location, are constructed as theaters-in-the-round to intensify the dynamic between actors and audience. the spectators are literally surrounded by the action and often become physical participants in the play. In unwalled takias, it is not unusual for combat scenes to occur behind the audience.[25]

Gallery

A man acting as Umar ibn Sa'ad whose army set fire to Imam Hussain's family tents, Iran

A man acting as Umar ibn Sa'ad whose army set fire to Imam Hussain's family tents, Iran.jpg) A shot from Ta'zieh

A shot from Ta'zieh Ta'zieh in Tajrish, Tehran

Ta'zieh in Tajrish, Tehran Ta'ziye in Shiraz Arts Festival,1977

Ta'ziye in Shiraz Arts Festival,1977_procession_Barabanki_India_(Jan_2009).jpg) Indian Shia

Indian Shia Tabuiks being lowered into the sea in Pariaman, Indonesia

Tabuiks being lowered into the sea in Pariaman, Indonesia Women Attending a Ta'Zieh 1800s

Women Attending a Ta'Zieh 1800s Persian Tekyeh for Ta'Zieh

Persian Tekyeh for Ta'Zieh.jpg) All actors use scripts during performance

All actors use scripts during performance

See also

- Hosay

- Islam in Iran

- tekyeh

- Muharram

- Lincoln Center Theater's 2002 production of a Ta'Zieh (videos on YouTube)

References

- Chelkowski, Peter (2003). "Time Out of Memory: Ta'ziyeh, the Total Drama". Asia Society. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- Beeman, William O. "Theatre History #27: Learning about Ta'Ziyeh with Dr. William O. Beeman." Audio Blog Post. Theatre History. HowlRound. 27 Mar 2017.

- Alizadeh, Farideh; Hashim, Mohd Nasir (2016). "When the attraction of Ta'ziyeh is diminished, the community should inevitably find a suitable replacement for it". 3 (1). doi:10.1080/23311983.2016.1190482. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Alizadeh, Farideh; Hashim, Mohd Nasir (2016). Ta'ziyeh-influenced Theate. ISBN 978-1519731791.doi:10.6084/m9.figshare.3511154 & doi:10.5281/zenodo.59379.svg

- Zarilli, Phillip B.; McConachie, Bruce; Williams, Gary Jay; Sorgenfrei, Carol Fisher (2006). Theatre Histories: An Introduction. USA: Routledge. pp. 81–82. ISBN 978-0-415-22727-8.

- Emami, Iraj (1987). The Evolution of Tradition Theatre and The Development of Modern Theatre in Iran. Scotland: University of Edinburgh. p. 48.

- Caron, Nelly (1975). "The Ta'Zieh, the Secret Theatre of Iran". The World of Music. 17 (4): 3–10. JSTOR 43620726.

- "TA'ZIA". Encyclopaedia Iranica. July 15, 2009. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- Iranian performance of Beethoven's 9th Symphony (BBC Persian)

- Iranian Theater Propagates Shiism

- Mottahedeh, Negar. "Ta'ziyeh; Karbala Drag Kings and Queens". Iran Chamber.

- Idem. "Narrative Painting and Painting Representation in Qajar Iran".

- Chelkowski, Peter (2010). "Identification and Analysis of the Scenic Space in Traditional Iranian Theatre". Eternal Performance: Ta'ziyeh and Other Shiite Rituals. India: Seagull. pp. 92–105. ISBN 978 1 9064 9 751 4.

- Chelkowski, Peter (2003). "Time Out of Memory: Ta'Zieh, The Total Drama". Asia Society. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- Reza Masoudi Nejad (2015). Peter van der Veer (ed.). Handbook of Religion and the Asian City: Aspiration and Urbanization in the Twenty-First Century. University of California Press. pp. 89–105. ISBN 978-0-520-96108-1.

- Specifically, Trinidad Sentinel 6 August 1857. Also, Original Correspondence of the British Colonial Office in London (C.O. 884/4, Hamilton Report into the Carnival Riots, p.18

- Peasants in the Pacific: a study of Fiji Indian rural society By Adrian C. Mayer

- Jihad in Trinidad and Tobago, July 27, 1990 By Daurius Figueira

- Korom, Frank J. (2003). Hosay Trinidad: Muharram Performances in an Indo-Caribbean Diaspora. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia. ISBN 978-0-8122-3683-5.

- Shankar, Guha (2003) Imagining India(ns): Cultural Performances and Diaspora Politics in Jamaica. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Texas, Austin pdf

- Bachyul Jb, Syofiardi (2006-03-01). "'Tabuik' festival: From a religious event to tourism". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 2007-01-27.

- Beyond Hindu and Muslim: Multiple Identity in Narratives from Village India By Peter Gottschalk, Wendy Doniger

- Toleration through the ages By Kālīpada Mālākāra

- Shabnum Tejani (2008). Indian Secularism: A Social and Intellectual History, 1890-1950. Indiana University Press. pp. 58–61. ISBN 978-0-253-22044-8.

- "THE PASSION OF HOSAYN". Encyclopedia of Iranica. Retrieved 2008-01-19.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ta'zieh. |

- Passion play an article by Encyclopædia Britannica online

- The passion (ta¿zia) of Husayn ibn 'Ali by Peter Chelkowski, an article of Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Nasser Taghvaee's documentary: Tamrin e Akhar (BBC Persian)

- Abbas Kiarostami on Tazieh (BBC Persian)

- Ta'zieh, the Persian Passion Play

- Ta'zia by Peter Chelkowski in Encyclopædia Iranica

- Combining creed with culture

- The Legality of making figurine effigy (Taziyah) of the shrine

- https://www.era.lib.ed.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/1842/7362/381673.