Chlorite group

The chlorites are a group of phyllosilicate minerals. Chlorites can be described by the following four endmembers based on their chemistry via substitution of the following four elements in the silicate lattice; Mg, Fe, Ni, and Mn.

| Chlorite group | |

|---|---|

| |

| General | |

| Category | Phyllosilicates |

| Formula (repeating unit) | (Mg,Fe) 3(Si,Al) 4O 10(OH) 2·(Mg,Fe) 3(OH) 6 |

| Crystal system | Monoclinic 2/m; with some triclinic polymorphs. |

| Identification | |

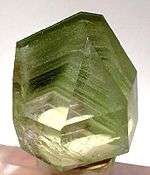

| Color | Various shades of green; rarely yellow, red, or white. |

| Crystal habit | Foliated masses, scaley aggregates, disseminated flakes. |

| Cleavage | Perfect 001 |

| Fracture | Lamellar |

| Mohs scale hardness | 2–2.5 |

| Luster | Vitreous, pearly, dull |

| Streak | Pale green to grey |

| Specific gravity | 2.6–3.3 |

| Refractive index | 1.57–1.67 |

| Other characteristics | Folia flexible – not elastic |

In addition, zinc, lithium, and calcium species are known. The great range in composition results in considerable variation in physical, optical, and X-ray properties. Similarly, the range of chemical composition allows chlorite group minerals to exist over a wide range of temperature and pressure conditions. For this reason chlorite minerals are ubiquitous minerals within low and medium temperature metamorphic rocks, some igneous rocks, hydrothermal rocks and deeply buried sediments.

The name chlorite is from the Greek chloros (χλωρός), meaning "green", in reference to its color. They do not contain the element chlorine, also named from the same Greek root.

Chlorite structure

The typical general formula is: (Mg,Fe)

3(Si,Al)

4O

10(OH)

2·(Mg,Fe)

3(OH)

6. This formula emphasizes the structure of the group.

Chlorites have a 2:1 sandwich structure (2:1 sandwich layer = tetrahedral-octahedral-tetrahedral = t-o-t...), this is often referred to as a talc layer. Unlike other 2:1 clay minerals, a chlorite's interlayer space (the space between each 2:1 sandwich filled by a cation) is composed of (Mg2+, Fe3+)(OH)

6. This (Mg2+, Fe3+)(OH)

6 unit is more commonly referred to as the brucite-like layer, due to its closer resemblance to the mineral brucite (Mg(OH)

2). Therefore, chlorite's structure appears as follows:

- -t-o-t-brucite-t-o-t-brucite ...

That's why they are also called 2:1:1 minerals.

An older classification divided the chlorites into two subgroups: the orthochlorites and leptochlorites. The terms are seldom used and the ortho prefix is somewhat misleading as the chlorite crystal system is monoclinic and not orthorhombic.

Occurrence

Chlorite is commonly found in igneous rocks as an alteration product of mafic minerals such as pyroxene, amphibole, and biotite. In this environment chlorite may be a retrograde metamorphic alteration mineral of existing ferromagnesian minerals, or it may be present as a metasomatism product via addition of Fe, Mg, or other compounds into the rock mass. Chlorite is a common mineral associated with hydrothermal ore deposits and commonly occurs with epidote, sericite, adularia and sulfide minerals. Chlorite is also a common metamorphic mineral, usually indicative of low-grade metamorphism. It is the diagnostic species of the zeolite facies and of lower greenschist facies. It occurs in the quartz, albite, sericite, chlorite, garnet assemblage of pelitic schist. Within ultramafic rocks, metamorphism can also produce predominantly clinochlore chlorite in association with talc.

Experiments indicate that chlorite can be stable in peridotite of the Earth's mantle above the ocean lithosphere carried down by subduction, and chlorite may even be present in the mantle volume from which island arc magmas are generated.

Chlorite occurs naturally in a variety of locations and forms. For example, chlorite is found naturally in certain parts of Wales in mineral schists.[1] Chlorite is found in large boulders scattered on the ground surface on Ring Mountain in Marin County, California.[2]

Members of the chlorite group

Baileychlore IMA1986-056 (Zn,Fe2+,Al,Mg)

6(Al,Si)

4O

10(O,OH)

8Borocookeite IMA2000-013 LiAl

4(Si

3B)O

10(OH)

8Chamosite year: 1820 (Fe,Mg)

5Al(Si

3Al)O

10(OH)

8Clinochlore year: 1851 (Mg,Fe2+)

5Al(Si

3Al)O

10(OH)

8Cookeite year: 1866 LiAl

4(Si

3Al)O

10(OH)

8Donbassite year: 1940 Al

2[Al

2.33][Si

3AlO

10](OH)

8Gonyerite year: 1955 (Mn,Mg)

5(Fe3+)

2Si

3O

10(OH)

8Nimite year: 1968 (Ni,Mg,Al)

6(Si,Al)

4O

10(OH)

8Pennantite year: 1946 (Mn

5Al)(Si

3Al)O

10(OH)

8Ripidolite chlinochlore var. (Mg,Fe,Al)

6(Al,Si)

4O

10(OH)

8Sudoite IMA1966-027 Mg

2(Al,Fe)

3Si

3AlO

10(OH)

8

Clinoclore, pennantite, and chamosite are the most common varieties. Several other sub-varieties have been described. A massive compact variety of clinochlore used as a decorative carving stone is referred to by the trade name seraphinite. It occurs in the Korshunovskoye iron skarn deposit in the Irkutsk Oblast of Eastern Siberia.[3]

Distinguishing from other minerals

Chlorite is so soft that it can be scratched by a finger nail. The powder generated by scratching is green. It feels oily when rubbed between the fingers. The plates are flexible, but not elastic like mica.

Talc is much softer and feels soapy between fingers. The powder generated by scratching is white.

Mica plates are elastic whereas chlorite plates are flexible without bending back.

Uses

Various types of chlorite stone have been used as raw material for carving into sculptures and vessels since prehistoric times.

See also

References

- Greenly E (1902). "The Origin and Associations of the Jaspers of South-eastern Anglesey". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society. 58 (1–4): 425–440. doi:10.1144/GSL.JGS.1902.058.01-04.29.

- Hogan MC (2008). Burnham A (ed.). "Ring Mountain Carving". The Megalithic Portal.

- "Seraphinite: Mineral information, data and localities". www.mindat.org. Retrieved 22 Mar 2019.

- Hurlbut CS, Klein C (1985). Manual of Mineralogy (20th ed.). New York: Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0471805807.

- Grove TL, Chatterjee N, Parman SW, et al. (2006). "The influence of H2O on mantle wedge melting". Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 249 (1–2): 74–89. Bibcode:2006E&PSL.249...74G. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2006.06.043.

- "The Mineral Chlorite". Amethyst Galleries. 1996. Archived from the original on 25 Nov 2004. Retrieved 22 Mar 2019.

- "Chlorite Group: Mineral information, data and localities". Mindat.org. Retrieved 22 Mar 2019.

- "Chlorite". Maricopa.edu. Archived from the original on 12 Nov 2014. Retrieved 22 Mar 2019.]

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chlorite. |