Strategic Air Command in the United Kingdom

Between 1948 and 1992, personnel and aircraft of the US Strategic Air Command (SAC) were deployed to bases in England. An informal agreement to base SAC bombers in the UK was reached between US General Carl Spaatz, and Marshal of the Royal Air Force (RAF) Lord Tedder, in July 1946. At that time there were only three bases in the UK capable of operating the SAC's Boeing B-29 Superfortress: RAF Lakenheath, RAF Marham and RAF Sculthorpe. These were airbases that had been extended during World War II when there were plans to use B-29s against Germany. When the Berlin Blockade began in June 1948, two B-29 groups deployed to the UK, but neither was equipped with Silverplate bombers capable of carrying nuclear weapons. Nuclear-capable Boeing B-50 Superfortress bombers began deploying in 1949, and nuclear bombs followed in 1950.

| Bases of the United States Air Force Strategic Air Command in the United Kingdom | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War | |||||

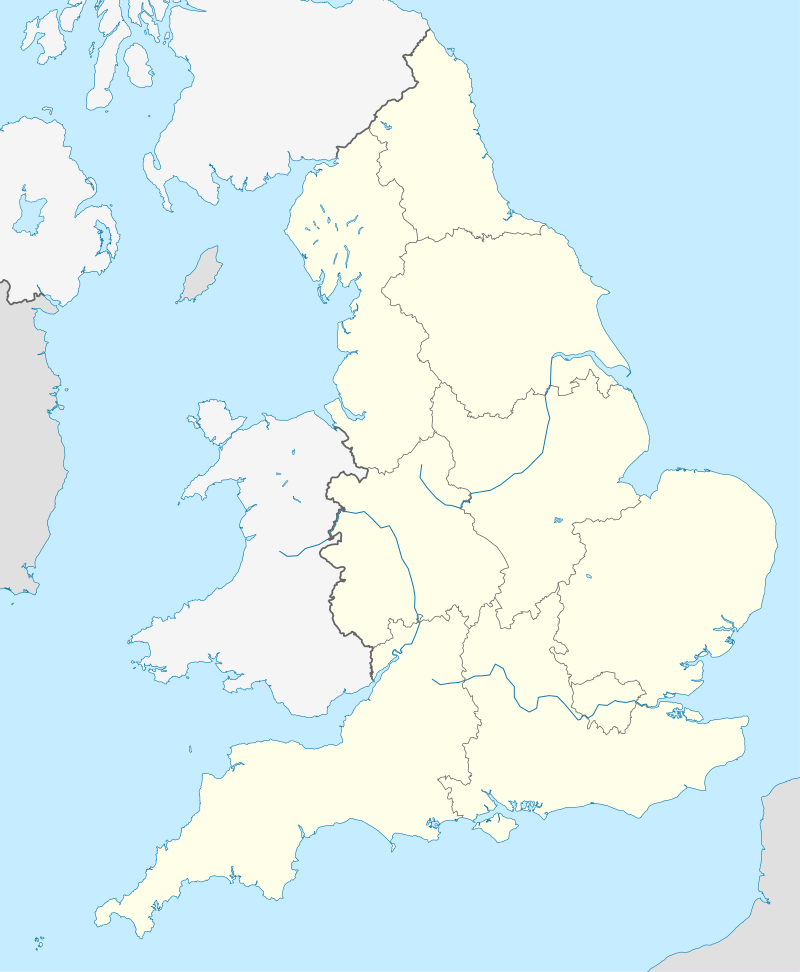

Sculthorpe Royal Air Force Stations used by the United States Air Force Strategic Air Command (red) and 7th Air Division headquarters (blue) | |||||

| |||||

The original bases in East Anglia were considered inadequate for the deployment of the forces called for called for in the Offtackle war plan, and there were concerns that they were exposed to a surprise attack from the North Sea. New bases were developed in the Midlands at RAF Brize Norton, RAF Upper Heyford, RAF Fairford and RAF Greenham Common were therefore developed as bases, which began to be used in 1952. The bases were initially manned by the RAF, were handed over to the USAF in 1951. They continued to be known as RAF stations, and the Royal Air Force Ensign was flown alongside the flag of the United States. The B-29 groups on the UK and the deport at RAF Burtonwood were placed under the 3rd Air Division. It became the Third Air Force in 1951, and SAC activated the 7th Air Division to control SAC forces in the UK.

In 1953 the propeller-driven B-29s and B-50s were replaced with Boeing B-47 Stratojet deployments to English bases. These temporary duty postings (TDY) typically involved an entire wing of 45 B-47s, along with 20 Boeing KC-97 Stratofreighter aerial refuelling tankers, which were held at readiness at an English base for ninety days. In 1958 TDY postings were replaced by a new system of overseas deployments called Reflex. A permanent SAC presence was established, with a SAC airbase group permanently assigned to each base, and the ninety-day deployments were replaced by twenty-one day deployments of two or three aircraft and crews. These aircraft were kept on full alert status for two weeks, which meant bombers and tankers were on the runway, fuelled and armed with a Mark 39 nuclear bomb, and ready to take off at 15 minutes notice. SAC B-47s in the UK were on alert during the Berlin Crisis of 1961 and the Cuban Missile Crisis, as were Thor missiles manned by RAF units, but with the warheads in the custody of SAC officers who controlled their launch through a dual key system.

With the introduction of intercontinental ballistic missiles and long-range Boeing B-52 Stratofortress bombers, SAC no longer required bases in the UK, and Reflex deployments ceased in 1965, but SAC bombers continued to visit, and the UK was used by the Lockheed U-2 and Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird reconnaissance aircraft. SAC Boeing KC-135 Stratotanker and McDonnell Douglas KC-10 Extender tankers based in the UK supported the abortive 1980 hostage rescue attempt in Iran and the 1986 United States bombing of Libya, and in 1991 joined B-52 bombers temporarily based in the UK to conduct bombing in Operation Desert Storm in 1991.

Early Cold War Tensions

Cold War tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union began as early as 1946. In June and July, the Chief of the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF), General Carl Spaatz, met with the Chief of the Air Staff, Marshal of the Royal Air Force Lord Tedder. The two were wartime comrades and had a warm, personal relationship.[1] US war plans for a conflict with the Soviet Union assumed that Western Europe would be overrun, and a fighting withdrawal conducted to the Pyrenees. Strategic air operations would be carried out from the UK.[2][3] Spaatz was interested in acquiring base facilities in the UK for B-29 Superfortress bombers armed with atomic bombs. Tedder agreed to provide them. Spaatz briefed to President Harry S. Truman on his return,[4] and the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Clement Attlee may have been informed of this informal agreement, but the Foreign Office and State Department were not.[5]

In August 1946, Colonel Elmer E. Kirkpatrick, who had developed of the base facilities on Tinian used for the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, arrived in the UK to discuss the requirements.[4] The B-29 was a large and underpowered aircraft. It required a runway at least 50 metres (150 ft) wide and 2,100 metres (7,000 ft) long, with at least 300 metres (1,000 ft) of clearance at both ends, and strong enough to bear the load of a 54,000-kilogram (120,000 lb) aircraft with a Fat Man atomic bomb in the forward bomb bay, which required a concrete slab at least 40 centimetres (15 in) thick. The Fat Man also required special storage facilities and assembly workshops, as the bombs could only be assembled shortly before a mission. This required a specialised Armed Forces Special Weapons Project (AFSWP) team to be deployed from Sandia Base. Since there was insufficient clearance for a Fat man under a B-29, loading was accomplished by driving the B-29 over a pit.[6]

In 1946, there were three bases in the UK that met these requirements: RAF Lakenheath, RAF Marham and RAF Sculthorpe. These airbases had been extended to a width of 61 metres (200 ft) and length of 2,400 metres (8,000 ft) in 1944 when there were plans to use B-29s against Germany.[6] No B-29 operations were conducted from the UK during the war, but three B-29s were stationed at RAF Mildenhall from March to October 1946 as part of Project Ruby, an evaluation of whether the B-29 could be modified to use the British Tallboy and Grand Slam bombs.[7]

A survey of 105 airfields in the UK found another 23 suitable to be extended for use with the B-29.[6] A meeting chaired by Air Vice-Marshal John Whitworth-Jones was held at the Air Ministry on 26 August to discuss the required works. In attendance was Sir Ernest Holloway, the Air Ministry's Director General of Works, who had directed the construction of airfields for the USAAF during the war. Works at Lakenheath and Sculthorpe involved the construction of pits near the hardstands, and the erection of additional buildings. The work was costed at £12,350 for each base, and were authorised on Holloway's personal authority. Hydraulic lift equipment for the loading pits arrived from Kirtland Army Air Field in September.[8]

Two incidents in August 1946, in which one USAAF C-47 transport aircraft was forced down over Yugoslavia,[9] and another was shot down ten days later,[10] prompted Truman to order the Strategic Air Command (SAC) to stage a show of force as a warning to the Soviet Union to keep its client states under control. In November, six B-29s bombers from SAC's 43rd Bombardment Group were deployed to Rhein-Main Air Base in Germany, and for nearly two weeks they flew along the borders of Soviet-occupied territories and paid visits to bases of friendly countries, including the UK, thereby evaluating their suitability for future use.[3] None of them were Silverplate bombers capable of carrying nuclear weapons; the US had only 17 of these at the time, all of which were assigned to the 509th Bombardment Group at Roswell Army Airfield in New Mexico.[11]

SAC B-29s began deploying to Europe on a regular basis in 1947,[lower-alpha 1] and during that year, ten aircraft of the 340th Bombardment Squadron , 97th Bombardment Group deployed from Smoky Hill Air Force Base to Giebelstadt Army Airfield in Germany, for a thirty day training/goodwill tour. Nine of them visited RAF Marham in a goodwill visit, where they were greeted by Lord Tedder and Major General Clayton Bissell, the US air attaché in the UK. Three of the bombers had been modified to carry Tallboys, which entered US service as the M-121. This revealed that despite the work carried out thus far, the air bases in the UK were ill-prepared to conduct B-29 operations.[13][3]

B-29 deployments

Berlin Blockade

When the Berlin Blockade began in June 1948, one B-29 squadron, the 353d Bombardment Squadron from the 301st Bombardment Group, was temporarily stationed at Fürstenfeldbruck Air Base in Germany.[14] The group's other two squadrons deployed to Germany in July.[15] The Foreign Secretary, Ernest Bevin asked Truman to send bombers to the UK to beef up the defences.[16] In response, the 28th Bombardment Group from Rapid City Air Force Base in South Dakota deployed to RAF Scampton in Lincolnshire, and the 307th Bombardment Group from MacDill Air Force Base in Florida deployed to RAF Marham and RAF Waddington in Lincolnshire. Each group had three squadrons of ten B-29s. The first B-29 touched down on 17 July, piloted by Colonel John B. Henry Jr., the commander of the 28th Bombardment Group, who was greeted by Air Vice-Marshal Charles Guest, the Air Officer Commanding No. 1 Group RAF.[15] The RAF granted permission, on the usual informal basis, for the USAF to reopen the wartime USAAF depot at RAF Burtonwood, and soon 2,500 USAF personnel were stationed there.[17]

The Secretary of State for Air, Sir Arthur Henderson, announced that the two groups were in the UK on temporary duty, and noted that "Units of the USAF do not visit this country under a formal treaty but under informal and long-standing arrangements between USAF and RAF for visits of goodwill and training purposes."[18] Neither the of two groups deployed to the UK, nor the 301st Bombardment Group in Germany, was equipped with the Silverplate/Saddletree B-29s capable of carrying atomic bombs.[lower-alpha 2] Nor was the 2nd Bombardment Group, which arrived in August.[20] Some confusion was caused by the arrival of "Colonel Tibbets", but this was Colonel Kingston E. Tibbets, the SAC deputy chief of staff for Materiel, and not Colonel Paul W. Tibbets of Hiroshima fame.[21]

The B-29 groups on the UK and the deport at RAF Burtonwood were placed under the newly formed B-29 Task Force at RAF Marham on 2 July. On 16 July, this became the 3rd Air Division (Provisional), under the command of Colonel Stanley T. Wray. Major General Leon W. Johnson assumed command on 23 August. He moved his headquarters to Bushy Park on 8 September, and then to Victoria Park Estate (later, USAF Station) at RAF South Ruislip on 15 April 1949.[20][22]

The B-29s deployed during the Berlin Blockade conducted intensive training. Shell-Mex gave the USAF access to 30,000,000 litres (250,000 US bbl) of aviation spirit, enabling tankers at sea to divert to Bremen to supply the airlift.[23] An order for was placed for 910 tonnes (1,000 short tons) of 230-kilogram (500 lb) and 450-kilogram (1,000 lb) bombs with the British Joint Staff Mission in Washington, DC. British bombs could be used as the shackle fittings were interchangeable. This was soon superseded by an order for 47,000 tonnes (52,000 short tons) of bombs, and seven million rounds of ammunition. Four million rounds of ammunition was brought in from Germany. At least one B-29 shot itself down during live firing practice.[24]

Base development

The bases in the UK were still considered inadequate for the deployment of three groups, much less the six called for in the Offtackle war plan. In particular, there were concerns about and the lack of dispersed hardstands,[22] and the location of the bases in East Anglia, which SAC felt were exposed to a surprise attack from the North Sea. It wanted bases further west, where they would be batter protected by the existing radar and fighter defences. The Air Ministry and the 3rd Air Division conducted a search for available sites, and identified RAF Brize Norton and RAF Upper Heyford in Oxfordshire, RAF Fairford in Gloucestershire, and RAF Greenham Common in Berkshire as suitable.[25] Moreover, the RAF now wanted the existing bases back, as it needed bases for its own eight squadrons of B-29s, the first of which was delivered in March 1950, and was known in British service as the Washington B.1. SAC therefore relinquished RAF Marham back to RAF control.[26]

The Air Ministry estimated the cost of construction at the four airbases at £7.717 million (equivalent to £224 million in 2019), and asked for £1.8 million in the budget for fiscal year 1950. HM Treasury refused to even consider this request without a formal arrangement in place between the two governments. It soon became clear that the UK government felt that Britain's adverse financial situation did not permit more than the allocation of the land and a token contribution to the construction costs. The United States Ambassador to the United Kingdom, Lewis Douglas, and Aidan Crawley, the Under-Secretary of State for Air, reached an agreement in March and April 1950. The planned number of aircraft to be deployed rose inexorably, to 670 in peace and 1,800 in war, and by April 1952, the projected cost had risen from £35 million to over £70 million (equivalent to £1.75 billion in 2019), and the British government sought to limit its contribution to £17.5 million (equivalent to £437 million in 2019). In September 1953, the Secretary of State for Air, Lord De L'Isle, and the US Ambassador, Winthrop W. Aldrich, agreed that the US would pay all the costs of construction beyond the four original bases.[27]

To make the bases capable of handling the larger Convair B-36 Peacemaker and Boeing B-47 Stratojet, then under development, the runways at Upper Heyford and Greenham Common were extended to 3,000 metres (10,000 ft) by building on the overshoot areas, thereby minimising the loss of agricultural land but eroding the safety margin. In addition to extending the runways, infrastructure added included control towers, communications, runway lights, radio beacons, and ground-controlled approach equipment.[27] Having works carried out by the United States Army Corps of Engineers and British firms raised familiar problems of different terminology and work practices. Cold weather hampered construction, as did interruptions to the electricity supply caused by a national coal shortage. The different voltage used by the mains electricity supply meant that all equipment brought from the US required large transformers. There were also shortages of aviation spirit due to inefficient deliveries. Personnel found the accommodation provided austere, with no hot water, only pot bellied stoves for heat, dim light bulbs, and few or no recreational facilities.[26]

B-50 deployments

Nuclear weapons

In February 1949, the 92nd Bombardment Group deployed to RAF Sculthorpe, becoming the first B-29 group to use that base, and the 307th Bombardment Group deployed to RAF Lakenheath and RAF Marham. In May, the 509th Bombardment Group arrived in the UK, with two squadrons based at RAF Marham and one at RAF Lakenheath. This was the first deployment to the UK of B-29s capable of carrying nuclear weapons. It was replaced in August by the USAF's other nuclear-capable group, the 43rd Bombardment Group, which deployed to RAF Sculthorpe, Lakenheath and Marham.[28] In June 1948 it had become the first group to equip with the Boeing B-50 Superfortress, a post-World War II revision of the B-29 with new, more powerful Pratt & Whitney R-4360 Wasp Major engines, taller vertical stabiliser, hydraulic rudder boost, nose wheel steering, and other improvements. Nonetheless, it looked obsolescent - a piston-engine bomber in the jet age.[29] Neither group deployed with nuclear weapons,[28] but they practised atomic missions using M-107 Pumpkin bombs, which had the same ballistic characteristics as Fat Man bombs. Loading pits were only dug at Sculthorpe and Lakenheath; the technique was discarded in favour of jacking up the front of the aircraft hight enough to allow the dolly with the bomb to be placed under the bomb bay.[30]

On 3 September 1949, a WB-29 over the north Pacific Ocean detected a large radiation cloud. Analysis showed that this cloud was from an atomic explosion on the Asian mainland sometime between 26 and 29 August. The Soviet Union had an atomic bomb earlier than the US expected it.[31] The Cold War heated up with the outbreak of the Korean War in June 1950. There were fears—albeit without any evidence—that the war in Korea was a diversion for a Soviet attack in Europe. At the time there was only one group in the UK, the 301st Bombardment Group, which had arrived in May, and it was equipped only with conventional B-29s. Its deployment was the first time that a full group complement of 45 bombers had deployed. In response to the Korean War situation, two nuclear-capable B-50 groups, the 93rd and 97th Bombardment Groups, deployed to the UK in July.[32] They brought Mark 4 nuclear bombs, an improved version of the wartime Fat Man with them, but without the active cores. The commander of SAC, Lieutenant General Curtis Le May ordered that personnel carry side arms in case of sabotage or armed intervention by local communists.[33]

An act of sabotage did occur. On 23 July, four B-29s of the 301st Bombardment Group at RAF Lakenheath were damaged by their British Army guards, who damaged plexiglas panels and wing flaps, and punctured the tyres with their bayonets. Three soldiers were arraigned before secret courts martial. Two were found guilty of malicious damage, and sentenced to terms of imprisonment and discharge with ignominy. The British Army guards were replaced by US airmen, but the commander of the 301st Bombardment Group, Colonel Thomas W. Steed, protested that their use as airbase guards hampered his group's training and effectiveness. Soon after, Steed himself was put out of action when he was severely injured during an RB-50 training flight during which a crewman went berserk and Steed was struck on the head with a wrench, an injury that eventually forced his early retirement. The 3rd Air Division instituted more security measures, including fencing, guard dogs and restrictions on civilian access. Agriculture continued at RAF Lakenheath, which necessitated public access roads.[34]

Command arrangements

SAC units remained under Johnson's command, and he was the main point of contact between the USAF and the British government. He was not answerable to Le May, but to General Lauris Norstad, the Commander in Chief of United States Air Forces in Europe (USAFE). The USAF Director of Plans and Operations, Major General Samuel E. Anderson, proposed that a new air division be created within SAC to control the deployments. This proposal was accepted by the Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force, General Hoyt Vandenberg, and SAC activated the 7th Air Division at RAF South Ruislip on 20 March 1951. A command staff was assembled at Offutt Air Force Base in Nebraska under Brigadier General Paul T. Cullen, but the Douglas C-124 Globemaster II aircraft carrying Cullen, his staff, and personnel of the 509th Bombardment Group to the UK caught fire and was forced to ditch into the Atlantic. There were no survivors. Major General Archie J. Old, the designated commander of the 5th Air Division in French Morocco assumed temporary command of the 7th Air Division until Major General John P. McConnell, Johnson's deputy, took over on 24 May, and Old moved on to Morocco.[35][36][37] 7th Air Division headquarters was located at RAF South Ruislip until 1 July 1958, when it moved to RAF High Wycombe.[35]

The 3rd Air Division became the Third Air Force on 1 May 1951, with Johnson still in command, until he was succeeded by Major General Francis H. Griswold on 6 May 1952. Griswold became deputy commander of SAC and in turn was succeeded by Major General Roscoe C. Wilson, a former commander of the AFSWP, on 30 April 1954.[38][39] Third Air Force personnel were stationed in the UK on long-term tours of duty, normally three years, and therefore could bring their families with them, whereas the 7th Air Division personnel were deployed for ninety day rotations, and could not.[40] On 16 May 1951, the Third Air Force transferred jurisdiction over RAF Bassingbourn, RAF Lakenheath, RAF Lindholme, RAF Manston, RAF Marham, RAF Mildenheall, RAF Sculthorpe, RAF West Drayton and RAF Waddington to the 7th Air Division. Six more air bases, RAF Upper Heyford, RAF Brize Norton, RAF Fairford, RAF Greenham Common, RAF Woodbridge and RAF Carnaley, were transferred as they became available.[41]

The bases used by the USAF were initially manned by the RAF, but by the early 1950s it was facing severe financial and personnel shortages. Air Chief Marshal Sir George Pirie approached Johnson asking if the USAF could take over manning of the bases, thereby saving the RAF 1,000 personnel. Johnson agreed to do so, and in 1951 seven stations were handed over to the USAF. The bases continued to be known as RAF stations, and the senior RAF officer present was known as the "RAF commander and senior liaison officer". While the title to the land remained with the Air Ministry, the USAF had unlimited tenure so long as its presence was desirable.[42] Johnson's deft touch in dealing with the British was perhaps exemplified by his order that the Royal Air Force Ensign be flown over the US bases in the UK alongside the flag of the United States.[36]

Aerial refuelling and reconnaissance

Neither the B-29 nor the B-50 had the range to reach distant targets in the Soviet Union, so aerial refuelling techniques were developed. In 1948, 92 B-29s were converted to KB-29M tankers, and 74 B-29s, 57 B-50As and 44 TB-50Bs were modified to receive fuel from tankers. The first tanker units, the 43rd and the 509th Air Refueling Squadron, were formed in 1948, and in May 1949 eleven KB-29Ms of the 509th Air Refueling Squadron were the first to deploy to the UK. They were replaced by tankers of the 43rd Air Refueling Squadron in August and September. In May 1950, the 301st Air Refueling Squadron became the first tanker squadron to deploy all sixteen of its aircraft.[43][44]

SAC developed a new method of refuelling, the flying boom, and 116 B-29s were converted to the KB-29P configuration that employed it. A pair of KB-29Ps from the 93rd Air Refueling Squadron deployed to the UK in June 1951. Although SAC continued to use the KB-29P until 1957, the last KB-29P deployment to the UK was of the 2nd Air Refueling Squadron, which was at RAF Lakenheath from September to December 1952. The final KB-29M deployment was of the 43rd Air Refueling Squadron, which deployed to RAF Lakenheath from March to June 1943. The KB-29Ms were scrapped soon after.[43][44]

Four SAC RB-29As of the 16th Photographic Reconnaissance Squadron visited RAF Scampton in October and November 1948. One crashed at Bleaklow in Derbyshire, killing all 13 on board. Twelve RB-29As of the 23rd Strategic Reconnaissance Squadron deployed to RAF Sculthorpe from December 1949 to March 1950. The next deployment was the 72d Strategic Reconnaissance Squadron, which arrived there in May 1950. In response to the outbreak of the Korean War, it conducted a search for indications of an imminent Soviet attack on Western Europe, but found none. Two of the aircraft were lost in crashes. [45] The 301st Bombardment Wing, which deployed to RAF Brize Norton and RAF Upper Heyford from December 1952 to March 1953, was the final B-29 deployment to the UK, and the first SAC deployment to the new bases in the Midlands. They were replaced by the B-50As of the 43rd Bombardment Wing. Its departure in June marked the final deployment of that aircraft as well.[46]

B-36 deployments

The Convair B-36 Peacemaker had its origins in wartime plans to bomb Nazi Germany from the US in the event that the UK was overrun. This did not occur, and the project was given a low priority for scarce resources. It was revived when it was feared that China might collapse, leaving no airfields within B-29 range of Japan. This was overcome by the capture of the Mariana Islands, and the project lost priority again, but it was revived after the war to fill the need for an intercontinental bomber for the atomic mission.[47] It was not intended that B-36s would be based in the UK, although they might have to land there after returning from a combat mission. The first B-36s to visit to England were six B-36Ds of the 7th and 11th Bombardment Groups which arrived at RAF Lakenheath on 16 January 1951, along with three C-124s carrying spare parts and 195 support personnel. Another six B-36Ds had set out from Carswell Air Force Base in Texas but has been forced to return due to bad weather.[48]

Over the next six years, B-36s made several visits to the UK for short periods of time. On 7 February 1953, dense fog and inadequate GCA at RAF Fairford caused the crew of a B-36H from the 7th Bombardment Wing that was low on fuel and had failed at two landing attempts to bail out. The aircraft flew on for another 48 kilometres (30 mi) before crashing into a cow paddock in Wiltshire. All 14 crewmen survived, but most were killed in another crash in Texas on 11 December 1953. The 42nd Bombardment Wing visited RAF Upper Heyford and RAF Burtonwood between 15 and 23 September 1954, and nineteen of its B-36Ds, B-36Hs and B-36Js deployed to RAF Upper Heyford in September and October 1955. Sixteen B-36s visited RAF Burtonwood in 1956, while RAF Brize Norton also played host to some. On 18 October 1956, shortly before the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 and the Suez Crisis, sixteen B-36H and B-36Js of the 11th Bombardment Wing deployed to RAF Burtonwood for a week. This was the final B-36 deployment.[49][50]

B-47 deployments

Wing deployments

The B-47 jet bomber had been under development since 1944, and in the stringent financial situation of the early post-war years the USAF decided to prioritise development of the B-47 rather than purchase more B-50s.[51] Experience in the Korean War amply demonstrated what the SAC planners had long suspected: that propeller-driven bombers were no match for Soviet jet fighters, even at night,[52] and the B-29, B36 and B-50 bomber force was fast losing credibility as a deterrent.[53] Rushing the B-47 into service entailed a series of costly and extensive modifications,[51] and the aircraft had a frightful safety record; over its lifetime there were 203 crashes, representing a loss rate of around 10 percent,[54] resulting in 242 fatalities.[55] In May 1952, in preparation for the arrival of B-47s in the UK, SAC ruled that all runways had to be at least 3,400 metres (11,300 ft) long to permit operations in the scorching heat of the English summer. This entailed the acquisition of private land and re-routing of roads. In the face of strong opposition from local residents, SAC backed down, and acquiesced to 3,000-metre (10,000 ft) runways with 3,000-metre (10,000 ft) overruns, and B-47 operations would cease when it became too hot. As it was, only RAF Fairford and RAF Greenham Common had 3,000-metre (10,000 ft) runways, although RAF Bruntingthorpe and RAF Chelveston could be extended. RAF Brize Norton had a 3,000-metre (10,000 ft) runway but no overruns, RAF Upper Heyford was limited to 2,900 metres (9,600 ft) with no overruns, and RAF Sculthorpe, RAF Lakenheath and RAF Mildenhall could not be extended to more than 2,700-metre (9,000 ft).[56][57]

In 1953 the 7th Air Division began a system of B-47 Stratojet deployments to English bases. These temporary duty postings (TDY) generally involved an entire wing of 45 B-47s, together with approximately 20 Boeing KC-97 Stratofreighter tankers, being held at readiness at an English base for ninety days. At the end of the TDY period they were relieved by another wing that was, generally, stationed at a different airfield.[58] With a range of 5,600 kilometres (3,000 nmi), they relied on tankers, but a fully-loaded KC-97 could not fly faster than the stall speed of the B-47, so refuelling was done in a dive.[59][60] The first B-47s to visit the UK arrived on 7 April 1953, when the two aircraft of the 306th Bombardment Wing landed at RAF Fairford after flying non-stop from Limestone Air Force Base in Maine. After a short visit, they returned to MacDill Air Force Base. The 306th Bomb Wing was the first SAC unit to equip with the B-47B and was the first unit to deploy to the UK for a ninety day tour of duty. The Wing arrived at RAF Fairford on 4 June 1953 accompanied by 14 aircraft. A further fifteen B-47s followed over the next three days, bringing the Wing up to its full strength of 45 aircraft. One B-47 crashed at RAF Upper Heyford on 2 July. The wing remained returned to the US in September 1953.[61][62]

The 305th Bombardment Wing was the next Stratojet unit to deploy. The wing arrived at RAF Brize Norton in September 1953 and returned to the US in December 1953. The wing was accompanied during its deployment by KC-97 tankers, which deployed to RAF Mildenhall during the wing's ninety day tour of duty, and carried out air-to-air refuelling of the B-47s both on the trip to England and on their return to the States. The refuelling squadrons were normally assigned to a particular bomb wing for the entire period of their deployment. The 22nd Bombardment Wing followed. Its first fifteen B-47s departed March Air Force Base in California on 3 December, but on arrival at Limestone Air Force Base they found that RAF Upper Heyford was fogbound. They remained there until 11 December, when eight flew on to the UK. Five managed to land at RAF Upper Heyford. The other three had to divert to RAF Mildenhall or RAF Brize Norton. That day the remaining 30 aircraft arrived at Limestone, where they were again delayed by fog at RAF Upper Heyford. Twenty of the 37 aircraft prepared to fly to the UK on 19 December, but suffered icing, and the lone de-icing truck was able to de-ice only five in time. On 21 December, 20 B-47s set out for the UK, leaving 32 at Limestone with mechanical problems. The last aircraft reached RAF Heyford on 25 December, having taken over three weeks to get there. The return trip in March 1954 was much less eventful.[63]

When the 303rd Bombardment Wing deployed to RAF Greenham Common in March 1954, the runway failed, forcing the group to relocate to RAF Fairford. RAF Mildenhall was also closed for repairs until June 1956.[56][57] In October 1955, SAC identified main bases from which B-47s would launch attacks, post-strike bases to which they would return to re-arm and re-fuel, and emergency bases, to be used in case other bases were unavailable. The designated main bases were RAF Brize Norton, RAF Greenham Common, RAF Lakenheath and RAF Upper Heyford; the post-strike bases were RAF Chelveston, RAF Fairford and RAF Mildenhall; and the emergency bases were RAF Homewood Park (Heathrow Airport), RAF Lindholme and RAF Full Sutton. Each main and post-strike base would be visited by B-47 wings at least twice each year.[56]

Reflex deployments

In 1958 TDY postings were replaced by a new system of overseas deployments called Reflex. A permanent SAC presence was established,[64] with a SAC airbase group permanently assigned to each base: the 3909th at RAF Greenham Common,[65] 3910th at RAF Lakenheath,[66] 3911th at RAF Sculthorpe,[67] 3912th at RAF Bruntingthorpe,[68] 3913th at RAF Mildenhall,[69] 3914th at RAF Chelveston,[70] 3915th at RAF Marham,[71] 3916th at RAF Lindholme,[72] 3917th at RAF Manston,[73] 3918th at RAF Upper Heyford,[74] 3919th at RAF Fairford,[75] and 3920th at RAF Brize Norton.[76][77] Ninety-day deployments of entire wings were replaced by twenty-one-day deployments of two or three aircraft and crews that were kept on full alert status for two weeks, which meant bombers and tankers were on the runway, fuelled and armed with a Mark 39 nuclear bomb, and ready to take off at 15 minutes notice.[64] In addition to improving SAC's alert posture, Reflex resulted in considerable savings. The 1956 deployment of the 307th Bombardment Wing involved moving 1,600 personnel and 190 tons of cargo at a cost of $42,428,000 (equivalent to $306 million in 2019).[57] Reflex deployments reduced the cost by about 40 percent.[78] The last ninety-day rotation was of the 100th Bombardment Wing at RAF Brize Norton between December 1957 and April 1958.[79]

In July 1959, President Charles de Gaulle ordered all nuclear-capable US aircraft to leave France, and USAFE units based there had to relocate to West Germany or the UK. SAC therefore handed RAF Bruntingthorpe, RAF Chelveston, RAF Lakenheath and RAF Mildenhall over to USAFE.[80] Looking forward to 1965–1970, SAC planner believed that keeping the B-47 viable would require considerable amount of upgrades, including the installation of electronic countermeasures, air-to-surface missiles, and improved radar and terrain avoidance systems to permit operations at low level. Funds for such upgrades was scarce, and the cost-benefit was questionable. It was therefore decided that the B-47 would be phased out.[81] This was temporarily halted by the Berlin Crisis of 1961, when 48 B-47 bombers and 20 EB-47 electronic warfare stood alert in the UK, and the Cuban Missile Crisis the following year, which saw 56 B-47s and 22 EB-47s on alert in the UK.[82]

By the following year the Kennedy administration had become concerned at the drain on US gold reserves caused by payments to foreign countries in exchange for basing rights.[81] The British government saw things differently; the USAF presence in the UK was estimated to be worth £55 million (equivalent to £1.2 billion in 2019) to the British economy.[64] Reflex was terminated at RAF Fairford and RAF Greenham Common on 1 July 1964, and the two bases reverted to RAF control. In April 1965, Reflex ceased at RAF Brize Norton, which reverted to the RAF, and RAF Upper Heyford, which was transferred to the USAFE,[81] and the 7th Air Division was inactivated on 30 June 1965.[35]

Reconnaissance deployments

Besides B-47 bombers, English bases also played host to RB-47s, and EB-47s reconnaissance aircraft. During the 1950s and 1960s, aircraft became reliant on radars to track and intercept bombers. Penetrating these defences required knowledge of them, and electronic intelligence (ELINT) and communications intelligence (COMINT) became more important, in many cases replacing traditional photographic intelligence (PHOTINT). The first deployment was 8 RB-47s from the 3 squadrons of the 91st Strategic Reconnaissance Wing to RAF Fairford on 8 April 1954. In June 1956, RB-47Hs of the 55th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing specially configured for ELINT arrived at RAF Mildenhall for the first of a series of deployments that continued for the next 11 years. The detachment at RAF Mildenhall closed on 1 February 1958, but a detachment was established at RAF Brize Norton in January 1959.[83]

These units performed some of the most sensitive reconnaissance missions of the Cold War. On 1 July 1960, an RB-47H from RAF Brize Norton was shot down near but outside Soviet airspace. The two survivors, navigator Captain John R. McKone and co-pilot Captain Freeman "Bruce" Olmstead, were picked up by Soviet fishing trawlers, and held in Lubyanka prison in Moscow with Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) pilot Francis Gary Powers, who had been shot down in the 1960 U-2 incident in May. They were released in January 1961. This resulted in a change of procedure: henceforth, reconnaissance flights had to be approved by the Prime Minister of the UK.[84][85] The final RB-47H mission from the UK was flown on 18 May 1967.[86]

Thor missile deployments

During the 1950s, SAC pursued the development of an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) as a supplement to its bombers. Delays in the development of the ICBM, and political anxiety over the Soviet Union's deployment of intermediate range ballistic missile (IRBM) systems, led the United States Secretary of Defense, Charles E. Wilson, to order the USAF to develop an IRBM as a stopgap or fallback. This resulted in the development of the Thor missile.[87] Implicit in the decision to develop an IRBM was that it would be based overseas, as its 2,800-kilometre; 1,700-mile (1,500 nmi) range was insufficient to reach targets in the Soviet Union or China from the US.[88] The UK appeared to be the best prospect, both politically and strategically.[87] The United States Secretary of the Air Force, Donald A. Quarles, officially raised the matter with the British Minister of Defence, Sir Walter Monckton, and his Chief Scientific Advisor, Sir Frederick Brundrett, in July 1956.[89] The October 1957 Sputnik crisis made the missile gap a hot political issue. Wilson's successor, Neil H. McElroy, ordered that Thor be rushed into production despite SAC's concerns about its vulnerability and impended obsolescence when ICBMs became available.[87]

The first Thor missile arrived at RAF Lakenheath on a C-124 Globemaster II on 29 August, and was delivered to RAF Feltwell on 19 September. Fourteen were received by 23 December 1958.[90] The deployment involved the transport of 8,200 tonnes (18,000,000 lb) of equipment by sea, 10,000 to 11,000 tonnes (23,000,000 to 25,000,000 lb) by air in 600 flights by C-124 Globemaster IIs, and 77 by Douglas C-133 Cargomasters of the 1607th Air Transport Wing.[91] Thor was declared operational on 1 November 1959,[92] under an agreement that the USAF paid the cost of maintenance of the missiles for five years. [93] The 705th Strategic Missile Wing, which was activated at RAF Lakenheath on 20 February 1958, and moved to RAF South Ruislip on 15 March.[94] provided technical support to the RAF Thor squadrons.[95]

It was agreed that the missiles would be under British control, that target assignment would be a British responsibility in conjunction with the 7th Air Division,[96] and that they would be manned by the RAF as soon as personnel could be trained to operate them.[97] Each missile was supplied with its own 1.44-megaton-of-TNT (6.0 PJ) Mark 49 warhead which remained under US control.[95] A precedent here was Project E, under which US nuclear weapons for British use were held at RAF airbases under US custody. This arrangement was acceptable to the British government.[98] The re-entry vehicle , which contained the warhead, was mated with the Thor missile by personnel of the 99th Munitions Maintenance Squadron.[86] The practical difficulty with US custody of the warheads was that if they were all stored at RAF Lakenheath, it would take up to 57 hours to make the missiles operational. A dual key system was therefore devised. The RAF key started the missile and the USAF authorisation officer's key armed the warhead. This reduced the launch time to fifteen minutes.[99][100]

The deployment of Jupiter IRBMs to Italy and Turkey in 1961 prompted the Soviet Union to respond by attempting to deploy IRBMs in Cuba.[101] In turn, their discovery by the United States led to the Cuban Missile Crisis. SAC was placed on DEFCON 3 on 22 October 1962, and DEFCON 2 on 24 October. RAF Bomber Command moved to Alert Condition 3, equivalent to DEFCON 3, on 27 October. Normally between 45 and 50 Thor missiles were ready to fire in 15 minutes. Without altering the alert condition, the number of missiles ready to fire in 15 minutes was increased to 59. The dual key system was thereby put under strain due to the RAF and USAF personnel being on different states of readiness.[102][103] The crisis passed, and SAC reverted to DEFCON 3 on 21 November and DEFCON 4 on 24 November.[102][103]

With ICBMs becoming available, SAC did not foresee the Thor missiles making a substantial contribution to the nuclear deterrent after 1965. On 1 May 1962, the Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara, informed the British Minister of Defence, Harold Watkinson, that the US would not pay the maintenance support for Thor after 31 October 1964. Watkinson then informed him that the system would be phased out.[93] The last Thor missile departed the UK on 1 September 1963.[95]

Post Reflex era

B-1, B-52 and FB-111 deployments

It was never intended that the Boeing B-52 Stratofortress would be based in the UK, but it was thought that they might land there for post-strike reconstitution. Accordingly, works were undertaken at RAF Brize Norton, RAF Fairford, RAF Greenham Common and RAF Upper Heyford to accommodate them. This involved strengthening the runways and taxiways to take their weight, which was almost twice that of the B-47, and widening them to allow for their outrigger landing gear. On 16 January 1957, five B-52s from the 93rd Bombardment Wing at Castle Air Force Base in California attempted the first non-stop jet flight around the world. Three aircraft completed the 23,574 miles trip in an average time of 45.19 hours. Two aircraft diverted, with one landing at CFB Goose Bay in Newfoundland and the other at RAF Brize Norton. This aircraft, a B-52B (53–395) named City of Turlock became the first B-52 to land in the UK, and the first to land outside North America.[104][105]

During the later Cold War years, B-52s became regular visitors to the United Kingdom, turning up at bases such as RAF Greenham Common and also taking part in RAF Bomber competitions, but were deployed to NATO on an individual basis, not as groups or wings. In 1962 there were one or two visits each month.[104] Convair B-58 Hustlers also visited several times, the first occasion being a Hustler from the 305th Bombardment Wing on 16 October 1963. The last visit was a lone Hustler from the 43rd Bombardment Wing on 16 May 1969, not long before the last of the Hustlers was retired in January 1970.Two General Dynamics FB-111As visited RAF Marham in March and April 1971 for an RAF bombing competition, and two visited for a NATO exercise in July and August 1986. The following month a lone FB-111A paid a visit to RAF Fairford for the Royal International Air Tattoo. There were also some visits by SAC Rockwell B-1 Lancers in 1989, 1990 and 1991.[106]

Refuelling operations

In the wake of the 1973 Arab-Israeli War and the subsequent oil embargo, the Spanish government sought to restrict US use of bases there. The agreement reached on 24 January 1976 permitted only a small Boeing KC-135 Stratotanker detachment to remain in Spain, so the rest relocated to RAF Mildenhall. On 15 August 1976, the 306th Strategic Wing at Ramstein Air Base in West Germany assumed operational control of SAC air refuelling and reconnaissance resources in Europe. It relocated to RAF Mildenhgall on 1 July 1978, and remained there until it was inactivated on 31 March 1992.[107] In 1977 the USAF announced plans to reactivate Greenham Common to house a squadron of KC-135s, due to a lack of capacity at RAF Mildenhall. This led to widespread local opposition, and in 1978 the British Defence Secretary vetoed the plan.[108] Instead, RAF Fairford was reopened and the 11th Strategic Group activated with the aerial refuelling mission.[109] The growing SAC presence with refuelling tankers and aerial reconnaissance led to the reactivation of the 7th Air Division at Ramstein Air Base on 1 July 1978.[35]

In November 1979, Iranian students seized control of the US embassy in Tehran and took the staff hostage, demanding the return of the Shah of Iran, who had fled to the United States. In April 1980, President Jimmy Carter authorised Operation Eagle Claw, a rescue attempt. Tanker support was for the operation was provided by eight KC-135 tankers of that deployed via RAF Mildenhall. Three KC-135 tankers from the 305th Air Refueling Wing flew from RAF Mildenhall to Cairo West Air Base to support the operation on 21 April, and two tankers from the 116th Air Refueling Squadron and 19th Bombardment Wing flew from RAF Mildenhall to Lajes Field in Portugal to refuel a formation of C-130 Hercules transports en route to Egypt. Two more tankers deployed to Cairo West Air Base on 22 April, and one from the 379th Bombardment Wing refuelled a second formation of C-130 transports bound for Egypt. While tanker operations went well, the operation was a complete failure; seven aircraft were lost and eight servicemen died, and the hostages were not freed.[110]

When hostilities erupted between the United States and Libya in March 1986, President Ronald Reagan authorised air strikes on Libyan military installations by US Navy aircraft carriers USS America and USS Coral Sea in the Mediterranean Sea and USAFE F-111s based in the UK. The 11th Strategic Group was reinforced with additional McDonnell Douglas KC-10 Extender tankers deployed from Spain and the United States, so that RAF Fairford hosted seven KC-10s and two KC-135s, and RAF Mildenhall had 12 KC-10s and eight KC-135s. As several countries refused permission for the F-111s to overfly their territory, the F-111s had to fly a 11,900-kilometre (6,400 nmi) mission from the UK to Libya via the Straits of Gibraltar, only 370 kilometres (200 nmi) shorter than the British Operation Black Buck missions in the Falklands War.[111]

%2C_USA_-_Air_Force_AN0894294.jpg)

The KC-10s were chosen as the primary refuelling agents for the mission as they had a larger fuel capacity than the KC-135s, but the short 2,700-metre (9,000 ft) runway at RAF Mildenhall did not permit them to take off fully loaded, so they were topped off by KC-135s en route. Three aerial refuellings were required on the outbound leg and two on the return one, but the F-111 crews had only recently deployed to the UK in January 1986, and were inexperienced in refuelling from KC-10s. To mitigate this, each F-111 was assigned a particular tanker for the entire mission, so the pilots could become familiar with their flying boom operator. When they returned to the tankers low on fuel after the raids, the F-111s latched onto the first tanker they saw, which caused some confusion, as one F-111 was lost. The KC-10 force remained in the UK for several days in case a follow up strike was called for, but none was, and they eventually returned to the US.[111]

Desert Storm

After forty years of SAC bomber deployments in the UK, their first combat operations to be conducted from UK bases came in Operation Desert Storm, when B-52s used RAF Fairford as a forward operating base. The 806th Bombardment Wing (Provisional) was activated at RAF Fairford using staff of the 97th Bombardment Wing from Eaker Air Force Base in Arkansas. Ten B-52s were deployed from various units: one from the 2nd Bombardment Wing, two from the 416th Bombardment Wing, and seven from the 379th Bombardment Wing. Crews were drawn from the 62nd Bombardment Squadron of the 2nd Bombardment Wing from Barksdale Air Force Base in Louisiana, the 328th Bombardment Squadron of the 93rd Bombardment Wing from Castle Air Force Base in California, the 524th Bombardment Squadron of the 379th Bombardment Wing from Wurtsmith Air Force Base in Michigan, and the 668th Bombardment Squadrons of the 416th Bombardment Wing from Griffiss Air Force Base in New York. Between 8 and 27 February 1991, the flew 62 sorties, and delivered 1,158 tonnes (1,140 long tons; 1,276 short tons) of bombs.[112]

Reconnaissance

RC-135 deployments

For many years various types of Boeing RC-135 reconnaissance aircraft were observed regularly arriving and departing from the RAF Mildenhall runway. Most of these aircraft had the capability to receive radar and radio signals from far behind the borders of the Communist Eastern Bloc. From Mildenhall the RC-135s flew ELINT and COMINT missions along the borders of Poland, the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia. The twenty or so specialists on board the RC-135s during such missions listened to and recorded military radio frequencies and communications. Following the retirement of the RB-47Hs, four ELINT missions were flown by a KC-135R Rivet Jaw (59–1465) from RAF Upper Heyford in May 1967. It crashed at Offurt Air Force base on 17 July, and it was replaced by a KC-135R Rivet Stand (55–3121), which flew missions from RAF Upper Heyford in 1968. This was upgraded to Rivet Jaw configuration, which was renamed Cobra Jaw in December 1969. It flew missions in September and November, but during the latter MiG-17s escorting it fired their cannons. The aircraft completed the mission and returned unharmed.[113]

U-2 deployments

SAC RB-45s seconded to the RAF had conducted overflights of East Germany and the Soviet Union in 1952 and 1954, and a SAC RB-47E from RAF Fairford had overflown Murmansk in May 1954. The first of four CIA Lockheed U-2 aircraft arrived in the UK arrived at RAF Lakenheath in May 1956. The 1st Weather Reconnaissance Squadron as it was styled was actually CIA Detachment A, and its mission was overflights of the Soviet Union and its allies. Its aircraft were manned by a mix of civilian CIA and secxonded SAC pilots. The British government was troubled by the 1956 U-2 incident, but clung to the cover story that they were for weather surveillance.[114]

A CIA U-2 from the 4th Weather Reconnaissance Squadron (CIA detachment G) flew to RAF Upper Heyford to conduct missions over the Middle East in the lead up to the Six-Day War, but the British government refused permission, and asked for the aircraft to be withdrawn. CIA detachment G (now calling itself The 1130th Aerospace Technical Training Group) deployed to RAF Upper Heyford again in 1970 response to the War of Attrition. This time it had permission from the British government to fly from British-controlled Cyprus, but lacking permission to overfly France, it had to deploy via the Straits of Gibraltar. In all, thirty missions were flown from Cyprus.[114]

SAC U-2s flew High Altitude Sampling Program (HASP) missions from RAF Upper Heyford from August to October 1962 in response to Soviet nuclear tests. Between May and July 1975, SAC flew a series U-2 missions from the UK inside West Germany to evaluate the SAM defences in East Germany, choosing to fly from RAF Wethersfield so as not to disturb KC-135 and RC-135 operations from RAF Mildenhall. Although the mission was tactical in nature, it was flown by SAC because it operated the U-2s. The deployment was not a success, and one aircraft was lost.[114]

A SAC U-2 supported NATO exercises in 1976, and was successful enough for a more regular presence to be mooted. Between June and October 1977, 34 U-2 COMINT missions were flown. On 1 April 1979 Detachment 4 of the 9th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing arrived at Mildenhall to fly U-2 PHOTINT and COMINT missions. Some 80 sorties were flown in 1979 and 111 in 1980, some in response to the Polish crisis of 1980–1981. Detachment 4 was withdrawn on 22 February 1983.[115] They were replaced by the TR-1As of the 95th Reconnaissance Squadron of the 17th Reconnaissance Wing, which began flying PHOTINT and COMINT sorties from RAF Alconbury in October 1982. They were withdrawn in June 1991.[116]

Blackbird deployments

In 1969, the US government began negotiations to base the Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird in the UK. Agreement was reached with the UK government in 1970. A special SR-71 hangar was erected at RAF Mildenhall, and $50,000 (equivalent to $255 thousand in 2019) was allocated for concrete apron work. Although the Prime Minister, Edward Heath, gave permission for SR-71 sorties to be flown to observe the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, the Americans mistook British reticence for reluctance, and nine missions were flown from the US instead. On 1 September 1974, an SR-71 flew to RAE Farnborough for an air show, breaking the New York to London speed record on the way there, and the London to Los Angeles record on the way back.[117]

After this public relations success, regular deployments of SR-71s and their KC-135Q tankers to RAF Mildenhall began with training deployments in April and September 1976. The first Peacetime Aerial Reconnaissance Program (PARPRO) mission was flown in January 1977.[117] Thereafter, deployments were a regular occurrence until April 1984, when the British government finally gave permission for SR-71s to be permanently based at RAF Mildenhall. It is estimated that 919 SR-71 sorties were flown from the UK, including damage assessment missions after the air raids on Libya in 1986. The last SR-71 sortie was flown from the UK on 18 January 1990. [118]

After the end of the Cold War in 1991, SAC was replaced by a new unified command, the United States Strategic Command on 1 June 1992.[119]

Emblem gallery

Strategic Air Command

Strategic Air Command.png) Second Air Force

Second Air Force Eighth Air Force

Eighth Air Force Fifteenth Air Force

Fifteenth Air Force 7th Air Division

7th Air Division

See also

- United States Air Forces in Europe

- United States Air Force in the United Kingdom

Footnotes

- The Strategic Air Command was formed as part of the USAAF in March 1946 and transferred to the USAF when the latter was formed in September 1947.[12]

- The codename Silverplate became compromised, and was replaced by Saddletree on 12 May 1947. On 16 April 1948, this became part of Project Gem, which also involved winterisation and adding air refuelling capability.[19]

Notes

- Young 2007, pp. 119–120.

- Condit 1996, pp. 153–159.

- Hopkins 2019, p. 13.

- Young 2016, pp. 22–23.

- Young 2007, p. 121.

- Young 2016, pp. 18–21.

- "Project Ruby – a look at RAF Mildenhall's history > Royal Air Force Mildenhall > Article Display". United States Air Force. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- Young 2016, pp. 26–27.

- Wooldridge 1971, pp. 28–29.

- Wooldridge 1971, pp. 38–42.

- Campbell 2005, p. 61.

- Young 2016, p. 55.

- Young 2016, p. 24.

- Moody 1995, p. 206.

- Gunderson 2007, p. 40.

- Moody 1995, pp. 207–208.

- Duke 1985, p. 56.

- Duke 1987, p. 34.

- Campbell 2005, p. 23.

- Hopkins 2019, p. 35.

- Young 2007, pp. 124–125.

- Duke 1987, p. 47.

- Young 2016, p. 39.

- Young 2007, pp. 124–126.

- Young 2016, pp. 63–65.

- Hopkins 2019, pp. 15–16.

- Young 2016, pp. 65–70.

- Hopkins 2019, pp. 35–36.

- Knaack 1988, pp. 163–164, 169.

- Young 2016, pp. 80–81.

- Condit 1996, pp. 279–281.

- Hopkins 2019, pp. 35–39.

- Young 2016, pp. 42–43.

- Young 2016, pp. 47–53, 57.

- "Factsheets : 7 Air Division". Air Force Historical Research Agency. Archived from the original on 30 October 2012.

- Young 2016, pp. 106–109.

- Hopkins 2019, p. 16.

- "Third Air Force (USAFE)". Air Force Historical Research Agency. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- Young 2016, pp. 58, 114–115.

- Duke 1985, p. 178.

- Duke 1985, p. 120.

- Young 2016, pp. 115–116.

- Knaack 1988, pp. 490–492.

- Hopkins 2019, pp. 92–93, 96.

- Hopkins 2019, pp. 118–119.

- Hopkins 2019, p. 46.

- Knaack 1988, pp. 3–4, 8–12.

- Hopkins 2019, p. 42.

- "Bomber flew 30 miles without a crew". The Wiltshire Gazette and Herald. 6 February 2003. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- Hopkins 2019, pp. 43–45.

- Knaack 1988, pp. 99–100.

- Knaack 1988, p. 490.

- Hopkins 2019, p. 47.

- Boyne 2013, p. 79.

- Boyne 2013, p. 81.

- Hopkins 2019, pp. 54–55.

- Hopkins 2019, p. 201.

- Young 2016, pp. 70–71.

- Boyne 2013, pp. 81–82.

- Knaack 1988, p. 118.

- Knaack 1988, p. 109.

- Hopkins 2019, pp. 48–51.

- Hopkins 2019, pp. 51–52.

- Young 2016, p. 94.

- Fletcher 1989, p. 115.

- Fletcher 1989, p. 121.

- Willard 1988, p. 50.

- Willard 1988, p. 9.

- Fletcher 1989, p. 127.

- Willard 1988, p. 16.

- Willard 1988, p. 40.

- Willard 1988, p. 35.

- Willard 1988, p. 38.

- Fletcher 1989, p. 131.

- Fletcher 1989, p. 111.

- Willard 1988, pp. 8–9.

- "RAF Brize North 80th Anniversary Souvenir Magazine". -Royal Air Force. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- Hopkins 2019, p. 59.

- Hopkins 2019, pp. 54, 61.

- Hopkins 2019, p. 202.

- Hopkins 2019, pp. 64–66.

- Hopkins 2019, p. 61.

- Hopkins 2019, pp. 128–131.

- Hopkins 2019, pp. 133–134.

- "RB-47H Shot Down". National Museum of the United States Air Force. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- Hopkins 2019, pp. 137–138.

- Young 2016, pp. 95–97.

- Clark & Angell 1991, pp. 158–159.

- Boyes 2015, pp. 38–39.

- Wynn 1997, pp. 340–342.

- Owen, Kenneth (23 March 1960). "Thor Logistics". Flight. pp. 398–399. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- Hopkins 2019, p. 193.

- Wynn 1997, pp. 358–360.

- Ravenstein 1984, p. 293.

- Hopkins 2019, pp. 193–195.

- Young 2016, pp. 98–99.

- Boyes 2015, p. 55.

- Clark & Angell 1991, pp. 161–162.

- Moore 2010, p. 99.

- Young 2016, pp. 100–101.

- Schwarz, Benjamin (January–February 2015). "The Real Cuban Missile Crisis". Atlantic Monthly. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- Young 2016, pp. 265–269.

- Wynn 1997, pp. 347–348.

- Hopkins 2019, pp. 68–69.

- Brean, Herbert; Blair, Clay Jr. (23 January 1957). "B-52s Shrink a World". Life. Vol. 42 no. 4. pp. 21–27.

- Hopkins 2019, pp. 73–76.

- Hopkins 2019, pp. 106–107.

- "History". Greenham Common Control Tower. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- "11 Wing (USAF)". Air Force Historical Research Agency. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Hopkins 2019, pp. 111–112.

- Hopkins 2019, pp. 112–116.

- Hopkins 2019, pp. 87–90.

- Hopkins 2019, pp. 137–143.

- Hopkins 2019, pp. 145–148.

- Hopkins 2019, pp. 151–152.

- Hopkins 2019, pp. 156–157.

- Hopkins 2019, pp. 161–162.

- Hopkins 2019, pp. 167–170.

- Feickert, Andrew (3 January 2013). The Unified Command Plan and Combatant Commands: Background and Issues for Congress (PDF) (Report). Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

References

- Boyes, John (2015). Thor Ballistic Missile: The United States and the United Kingdom in Partnership. Fonthill. ISBN 978-1-78155-481-4. OCLC 921523156.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Boyne, Walter J. (February 2013). "The B-47's Deadly Dominance" (PDF). Air Force Magazine. 96 (2): 79–83. ISSN 0730-6784. Retrieved 9 May 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Campbell, Richard H. (2005). The Silverplate Bombers: A History and Registry of the Enola Gay and Other B-29s Configured to Carry Atomic Bombs. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-7864-2139-8. OCLC 58554961.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Clark, Ian; Angell, David (1991). "Britain, the United States and the Control of Nuclear Weapons: The diplomacy of the Thor Deployment 1956–58". Diplomacy & Statecraft. 2 (3): 153–177. doi:10.1080/09592299108405832. ISSN 0959-2296.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Condit, Kenneth W. (1996). The Joint Chiefs of Staff and National Policy, Volume II: 1947-1949 (PDF). History of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Washington, DC: Office of Joint History Office of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. OCLC 4651413. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- Duke, Simon (1985). US Defence Bases in the United Kingdom (DPhil thesis). Jesus College, University of Oxford. Retrieved 5 May 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Duke, Simon (1987). US Defence Bases in the United Kingdom: A Matter for Joint Decision?. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-18482-8. ISBN 978-0-333-43722-3. OCLC 1086552381.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fletcher, Harry R. (1989). Air Force Bases Volume II, Active Air Force Bases outside the United States of America on 17 September 1982 (PDF). Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama: Office of Air Force History. ISBN 0-912799-53-6. OCLC 18192421. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- Gunderson, Brian S. (Spring 2007). "Strategic Air Command's B-29s during the Berlin Airlift". Air Power History. 54 (1): 38–43. ISSN 1044-016X. JSTOR 26274812.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hopkins, Robert S. III (2019). Strategic Air Command in the UK: SAC operations 1946–1992. Manchester: Hikoki Publications. ISBN 978-1-902109-58-9. OCLC 1149748553.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Knaack, Marcelle Size (1988). Encyclopedia of U.S. Air Force Aircraft and Missile Systems: Volume II: Post-World War II Bombers, 1945–1973 (PDF). Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History. ISBN 0-912799-59-5. OCLC 631301640. Retrieved 5 May 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moody, Walton S. (1995). Building a Strategic Air Force (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Air Force History and Museums Program. OCLC 1001725427. Retrieved 2 May 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moore, Richard (2010). Nuclear Illusion, Nuclear Reality: Britain, the United States and Nuclear Weapons 1958–64. Nuclear Weapons and International Security since 1945. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 978-0-230-21775-1. OCLC 705646392.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ravenstein, Charles A. (1984). Air Force Combat Wings, Lineage & Honors Histories 1947-1977 (PDF). Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History. ISBN 0-912799-12-9. Retrieved 17 December 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Willard, Richard R. (1988) [1968]. Location of United States Military Units in the United Kingdom, 16 July 1948-31 December 1967. USAF Air Station, South Ruislip, United Kingdom: Historical Division, Office of Information, Third Air Force. LCCN 68061579.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wooldridge, Dorothy Elizabeth (May 1971). Yugoslav-United States Relations 1946-1947, Stemming from the Shooting of U.S. Planes Over Yugoslavia, August 9 and 19, 1946 (PDF) (MA). Rice University. Retrieved 29 April 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wynn, Humphrey (1997). RAF Strategic Nuclear Deterrent Forces, Their Origins, Roles and Deployment, 1946–1969. A documentary history. London: The Stationery Office. ISBN 0-11-772833-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Young, Ken (January 2007). "US 'Atomic Capability' and the British Forward Bases in the Early Cold War". Journal of Contemporary History. 42 (1): 117–136. doi:10.1177/0022009407071626. JSTOR 30036432.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Young, Ken (2016). The American Bomb in Britain: US Air Forces' Strategic Presence 1946–64. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-8675-5. OCLC 942707047.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Lloyd, Alwyn T. (2000), A Cold War Legacy, A Tribute to Strategic Air Command, 1946–1992, Pictorial Histories Pub ISBN 1-57510-052-5

- Robinson, Robert (1990), USAF Europe in Color, Volume 2, 1947–1963, Squadron/Signal Publications ISBN 0-89747-250-0

- Rodrigues, Rick (2006), Aircraft Markings of the Strategic Air Command 1946–1953, McFarland & Company ISBN 0-7864-2496-6

- Steijger, Cees (1991), A History of USAFE, Airlife Publishing Limited, ISBN 1-85310-075-7

.jpg)