Stipa-Caproni

The Stipa-Caproni, also generally called the Caproni Stipa, was an experimental Italian aircraft designed in 1932 by Luigi Stipa (1900–1992) and built by Caproni. It featured a hollow, barrel-shaped fuselage with the engine and propeller completely enclosed by the fuselage—in essence, the whole fuselage was a single ducted fan. Although the Regia Aeronautica (Italian Royal Air Force) was not interested in pursuing development of the Stipa-Caproni, its design influenced the development of jet propulsion.[1]

| Stipa-Caproni | |

|---|---|

| |

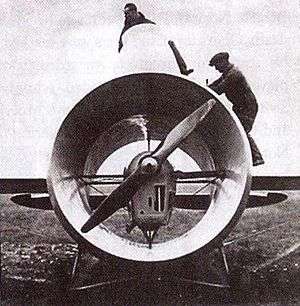

| The Stipa-Caproni, piloted by Caproni company test pilot Domenico Antonini, on a test flight on 7 October 1932. | |

| Role | Experimental aircraft |

| Manufacturer | Caproni |

| Designer | Luigi Stipa |

| First flight | October 7, 1932 |

| Primary user | Italy |

| Number built | 1 |

Stipa's design

Stipa's basic idea, which he called the "intubed propeller", was to mount the engine and propeller inside a fuselage that itself formed a tapered duct, or venturi tube, and compressed the propeller's airflow and the engine exhaust before it exited the duct at the trailing edge of the aircraft, essentially applying Bernoulli's principle of fluid movements to make the aircraft's engine more efficient. This is a similar principle as is used in turbofan engines but used a piston engine to drive the compressor/propeller rather than a gas turbine. Stipa later became convinced that German rocket and jet technology (especially the V-1 flying bomb) was using his patented invention without giving proper credit, although his ducted fan design had little mechanically in common with turbojet engines and nothing at all with the pulsejet used on the V-1.

Stipa spent years studying the idea mathematically while working in the Engineering Division of the Italian Air Ministry, eventually determining that the venturi tube's inner surface needed to be shaped like an airfoil in order to achieve the greatest efficiency. He also determined the optimum shape of the propeller, the most efficient distance between the leading edge of the tube and the propeller, and the best rate of revolution of the propeller. Finally, he petitioned the Italian Fascist government to produce a prototype aircraft. The government, seeking to showcase Italian technological achievement—particularly in aviation—contracted the Caproni company to construct the aircraft in 1932.[2]

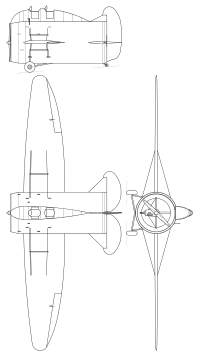

The resultant aircraft—a mid-wing monoplane of mostly wooden construction dubbed the Stipa-Caproni or Caproni Stipa. The fuselage was a barrel-like tube, short and fat, open at both ends to form the tapered duct, with twin open cockpits in tandem mounted in a hump on top of it. The wings were elliptical and passed through the duct and the engine nacelle inside it. The duct itself had a profile similar to that of the airfoils, and a fairly small rudder and elevators were mounted on the trailing edge of the duct, allowing the ducted propeller wash to flow directly over them as it exited the fuselage to improve handling. The propeller was mounted inside the fuselage tube, flush with the leading edge of the fuselage, and the 120-horsepower de Havilland Gipsy III engine that powered it was mounted within the duct behind it at the midpoint of the fuselage. The aircraft had low, fixed, spatted main landing gear and a tailwheel. It was painted in a blue-and-cream scheme of the type used on racing aircraft of the day, and its rudder bore the colors of the Italian flag.[2]

Test flights

The Stipa-Caproni first flew on 7 October 1932 with Caproni company test pilot Domenico Antonini at the controls. Initial testing showed that the "intubed propeller" design did increase the engine's efficiency as Stipa had calculated, and the additional lift provided by the airfoil shape of the interior of the duct itself allowed a very low landing speed of only 68 km/h (42 mph) and assisted the Stipa-Caproni in achieving a higher rate of climb than other aircraft with similar power and wing loading. The placement of the rudder and elevators in the exhaust from the propeller wash at the trailing edge of the tube gave the aircraft handling characteristics that made it very stable in flight, although they later were enlarged to further improve the plane's handling characteristics. The Stipa-Caproni proved to be noticeably quieter than conventional aircraft of the time. Unfortunately, the "intubed propeller" design also induced so much aerodynamic drag that the benefits in engine efficiency were cancelled out, and the aircraft's top speed proved to be only 131 km/h (81 mph).[3]

When Caproni had completed initial testing, the Regia Aeronautica took control of the plane and transferred it to Guidonia Montecelio for a brief series of further test flights. All test pilots reported that the plane was extremely stable in flight, to the point where it was difficult to change course; test pilots were also astounded by the very low landing speed and the consequent very short landing run.

As the plane did not perform noticeably better than conventional aircraft designs, the Regia Aeronautica decided to cancel further development. No further prototypes were built.

Influence

Stipa himself never had intended his "intubed propeller" to be employed on single-engine aircraft like the Caproni-Stipa—which he viewed merely as a testbed—instead envisioning its use in large, multi-engine flying wing aircraft he had been designing in which the aerodynamic drag properties would not be significant, and the Italian government publicized the Stipa-Caproni's design as an example of Italian aviation technology prowess. None of Stipa's flying-wing aircraft designs were built, but experiences collected with the Stipa-Caproni did become an important influence in the development of the motorjet-powered Caproni Campini N.1.[2]

The test flights of the Stipa-Caproni also sparked much academic interest, and resulted in Stipa's work being studied in France, Germany, Italy, and the United Kingdom, and by the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics in the United States. France designed—but never constructed—an advanced night bomber based on a Luigi Stipa design in the mid-1930s, and various aircraft designs such as the German Heinkel T fighter of 1940 are thought to have incorporated some of Stipa's ideas as demonstrated by the Stipa-Caproni.[2]

The Kort nozzle ducted fan of today—designed in Germany in 1934—uses many of Stipa's principles. The modern turbofan engine is thought by some aviation historians to be a descendant of the "intubed propeller" demonstrated in the Stipa-Caproni.[2]

Replica

In Australia, Lynette Zuccoli and Aerotec Queensland designed a 3/5-scale replica of the Stipa-Caproni, accurate even in terms of paint scheme and markings, powered by an Italian Simonini racing engine. They built it in 1998 and in October 2001 succeeded in making two directional test flights with it with Bryce Wolff at the controls. Each flight covered about 600 metres (660 yards) and reached an altitude of approximately 6 metres (20 feet), with Wolff reporting that the replica was very stable in flight and performed much as the Italian test pilots reported that the original aircraft had 69 years to the month earlier.[4] The replica may never have flown again, and is now on static display at Toowoomba Airfield in Australia.[2]

Operators

Specifications (original Stipa-Caproni)

Data from NACA Technical Memorandum nº 753 : Stipa Monoplane with Venturi Fuselage,[5] Aeroplani Caproni: Gianni Caproni and His Aircraft, 1910-1983[6]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1 or 2

- Length: 5.88 m (19 ft 3 in)

- Wingspan: 14.28 m (46 ft 10 in)

- Wing area: 19 m2 (200 sq ft)

- Empty weight: 570 kg (1,257 lb)

- Gross weight: 850 kg (1,874 lb)

- Powerplant: 1 × de Havilland Gipsy III 4-cylinder inverted air-cooled in-line piston engine, 90 kW (120 hp)

- Propellers: 2-bladed ground-adjstable propeller

Performance

- Maximum speed: 133 km/h (83 mph, 72 kn)

- Landing speed: 68 km/h (42 mph)

- Service ceiling: 3,700 m (12,100 ft)

- Time to altitude: 3,000 m (9,843 ft) in 40 minutes

- Wing loading: 44.73 kg/m2 (9.16 lb/sq ft) at 850 kg (1,874 lb)

- Power/mass: 0.105 kW/kg (0.064 hp/lb)

- Take-off run: 180 m (591 ft)

- Landing run: 180 m (591 ft)

References

- O.E. Lancaster, High Speed Aerodynamics and Jet Propulsion. Vol. XII: Jet Propulsion Engines, Princeton 1959 claims that "The Stipa Aero plane built by Caproni in 1932 should be classified as a Jet Aircraft. The Stipa Aero plane can be considered as a predecessor of the Jet Aircraft of today."

- Guttman, Robert (March 2010). "Caproni Flying Barrel: Luigi Stipa Claimed His 'Intubed Propeller' Was the Ancestor of the Jet Engine". Aviation History: 18–19. ISSN 1076-8858.

- Guttman, Aviation History, March 2010, p. 19.

- Legends in Our Own Lunchtimes: The Stipa Caproni

- Stipa, Luigi (7 July 1933). Stipa Monoplane with Venturi Fuselage, NACA Technical Memorandum nº 753. Washington D.C.: National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics.

- Abate, Rosario; Alegi, Gregory; Apostolo, Giorgio (1992). Aeroplani Caproni: Gianni Caproni and His Aircraft, 1910-1983. Trento: Associazione Musep d'ellAeronautica "G.Caproni". p. 245.

Further reading

- Thompson, Jonathon W. (1963). Italian Civil and Military Aircraft 1930-1945. USA: Aero Publishers Inc. p. 97. ISBN 0-8168-6500-0.

- Schramm, A. 'Hollow Fuselage Airplane', US Patent 2071221, feb 16, 1937.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stipa-Caproni. |