Grallator

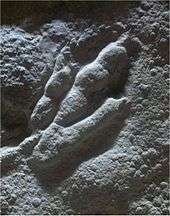

Grallator ["GRA-luh-tor"] is an ichnogenus (form taxon based on footprints) which covers a common type of small, three-toed print made by a variety of bipedal theropod dinosaurs. Grallator-type footprints have been found in formations dating from the Early Triassic through to the early Cretaceous periods. They are found in the United States, Canada, Europe, Australia, Brazil (Sousa and Santa Maria Formations) and China,[1] but are most abundant on the east coast of North America, especially the Triassic and Early Jurassic formations of the northern part of the Newark Supergroup.[2][3] The name Grallator translates into "stilt walker", although the actual length and form of the trackmaking legs varied by species, usually unidentified. The related term "Grallae" is an ancient name for the presumed group of long-legged wading birds, such as storks and herons. These footprints were given this name by their discoverer, Edward Hitchcock, in 1858.[2]

| Grallator | |

|---|---|

| |

| Typical footprint form | |

| Trace fossil classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Ichnofamily: | †Grallatoridae |

| Ichnogenus: | †Grallator Hitchcock, 1858 |

| Type ichnospecies | |

| G. cursorius Hitchcock, 1858 | |

| Ichnospecies | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Grallator footprints are characteristically three-toed (tridactyl) and range from 10 to 20 centimeters (or 4 to 8 inches) long. Though the tracks show only three toes, the trackmakers likely had between four and five toes on their feet. While it is usually impossible to match these prints with the exact dinosaur species that left them, it is sometimes possible to narrow down potential trackmakers by comparing the proportions in individual Grallator ichnospecies with known dinosaurs of the same formation. For example, Grallator tracks identified from the Yixian Formation may have been left by Caudipteryx.[3]

Newark Supergroup tracks

The most famous, and archetypal tracks that conform to the Grallator type are those found on the East Coast of North America, specifically from the Late Triassic to Early Jurassic Newark Supergroup. These footprints were likely made by an unidentified, primitive dinosaur similar to Coelophysis.[2] The Newark Supergroup footprints show digits II, III and IV, but no trace of the shorter digits I and V which would likely have been present in a dinosaur of this stage. The outer two digits would have been stubby and ineffective, not touching the ground during walking or running.[2] Despite losing most of their effectiveness, dinosaur evolution had not yet removed these digits to fully streamline the foot. This is known because rare specimens are found with traces of these outer digits. Digits II, III and IV have 3, 4 and 5 phalanges respectively, giving Grallator a ?-3-4-5-? digital formula.

Although the Newark Supergroup Grallator tracks were made by a bipedal saurischian dinosaur, they can easily be mistaken for those of the late Triassic ichnogenus Atreipus.[4] The trackmaker of Atreipus prints was a quadrupedal ornithischian. The reason for this similarity is a lack of divergence in the foot evolution of the two distinct groups of dinosaurs: ornithischians and saurischians.

Species[5]

- Subgenus G. (Coelurosaurichnus)

- G. (C.) palmipes

- G. (C.) p. exiguus (Ellenberger, 1970)

- G. (C.) palmipes

- Subgenus G. (Grallator)

- G. (G.) zvierzi Gierlinski, 1991

- G. andeolensis Gand, Vianey-Liaud, Demathieu, & Garric, 2000

- G. angustidigitus (Ellenberger, 1970)

- G. angustus (Ellenberger, 1974)

- G. a. cursor Ellenberger, 1974

- G. cursorius Hitchcock, 1858 (ichnotype)

- G. cuneatus Hitchcock, 1858

- G. damanei Ellenberger, 1970

- G. deambulator (Ellenberger, 1970)

- G. digitigradus (Ellenberger, 1974)

- G. emeiensis Zhen, Li, Han & Yang, 1995

- G. formosus Hitchcock, 1858

- G. gracilis Hitchcock, 1865

- G. graciosus (Ellenberger, 1970)

- G. grancier (Courel & Demathieu, 2000)

- G. ingens (Ellenberger, 1970)

- G. jiuquwanensis (Zeng, 1982) =Hunanpus

- G. kehli (Beurlen, 1950)

- G. kronbergeri (Rehnelt, 1959)

- G. lacunensis (Ellenberger, 1970)

- G. leribeensis (Ellenberger, 1970)

- G. limnosus Zhen, Li, & Rao, 1985

- G. madseni Irby, 1995

- G. magnificus (Ellenberger, 1970)

- G. matsiengensis Ellenberger, 1970

- G. maximus Lapparent & Monetnat, 1967

- G. minimus (Ellenberger, 1970)

- G. minor (Ellenberger, 1970)

- G. moeni (Beurlen, 1950)

- G. mokanametsongensis (Ellenberger, 1974)

- G. molapoi Ellenberger, 1974

- G. morijiensis (Ellenberger, 1970)

- G. moshoeshoei (Ellenberger, 1970)

- G. olonensis Lapparent & Monetnat, 1967

- G. palissyi (Gand, 1976)

- G. paulstris (Ellenberger, 1970)

- G. perriauxi (Demathieu & Gand, 1972)

- G. princeps (Ellenberger, 1970)

- G. protocrassidigitus (Ellenberger, 1970)

- G. rapidus (Ellenberger, 1974)

- G. romanovskyi (Gabunia & Kurbatov)

- G. quthingensis (Ellenberger, 1974)

- G. rectilineus (Ellenberger, 1970)

- G. sabinensis (Gand & Pellier, 1976)

- G. sassendorfensis (Kuhn, 1958)

- G. sauclierensis Demathieu & Sciau, 1992

- G. schlauersbachensis (Weiss, 1934)

- G. socialis (Ellenberger, 1970)

- G. ssatoi Yabe, Inai, & Shikama, 1940

- G. tenuis Hitchcock, 1858

- G. toscanus (Huene, 1941)

- G. variabilis Lapparent & Monetnat, 1967

Paleopathology

Fossil tracks can be informative about theropod pathologies but apparently pathological traits may be due to unusual behaviors. Sandstone stratum dating to the Norian in southern Wales preserves tracks of an individual with a deformed digit III attribute to the ichnogenus Anchisauripus. The distal end of the digit was consistently flexed. However, this apparent pathology could be caused by the animal rotating the tip of that digit when lifting the foot.[6]

See also

References

- Grallator at Fossilworks.org

- Weishampel, D.B. & L. Young. 1996. Dinosaurs of the East Coast. The Johns Hopkins University Press

- Xing Li-da, Harris, J.D., Feng Xiang-yang, and Zhang Zhi-jun. (2009). "Theropod (Dinosauria: Saurischia) tracks from Lower Cretaceous Yixian Formation at Sihetun Village, Liaoning Province, China and possible track makers." Geological Bulletin of China, 28(6): 705-712.

- Safran, J. and Rainforth, E.C. (2004). "Distinguishing the tridactyl dinosaurian ichnogenus Atreipus and Grallator: where are the latest Triassic Ornithischia in the Newark Supergroup?" Abstracts with Programs, Geological Society of America, 36(2): 96.

- "Paleofile". Retrieved 5 Apr 2011.

- Molnar, R. E., 2001, Theropod paleopathology: a literature survey: In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life, edited by Tanke, D. H., and Carpenter, K., Indiana University Press, p. 337-363.

Further reading

- Calvo, Jorge Orlando; Rivera, Cynthia (2018). "Huellas de dinosaurios en la costa oeste del embalse Ezequiel Ramos Mexía y alrededores (Cretácico Superior, Provincia de Neuquén, República Argentina)". Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana. 70 (2). pp. 449 ‒ 497.