Stefan Dragutin

Stefan Dragutin (Serbian: Стефан Драгутин, Hungarian: Dragutin István; c. 1244 – 12 March 1316) was King of Serbia from 1276 to 1282. From 1282, he ruled a separate kingdom which included northern Serbia, and (from 1284) the neighboring Hungarian banates (or border provinces), for which he was unofficially styled as "King of Syrmia". He was the eldest son of King Stefan Uroš I of Serbia and Helen of Anjou. He received the title of "young king" in token of his right to succeed his father after a peace treaty between Uroš I and Béla IV of Hungary who was the grandfather of Dragutin's wife, Catherine, in 1268. He rebelled against his father and forced him to abdicate with Hungarian assistance in 1282.

| Stefan Dragutin | |

|---|---|

King Dragutin, (founder's portrait (fresco) in Saint Achillius Church, painted during his lifetime, around 1296) | |

| King of Syrmia | |

| Tenure | 1282–1316 |

| Successor | Stefan Vladislav II of Syrmia |

| King of Serbia | |

| Tenure | 1276–1282 |

| Predecessor | Stefan Uroš I |

| Successor | Stefan Uroš II Milutin |

| Burial | Đurđevi Stupovi |

| Spouse | Catherine of Hungary |

| Issue | |

| Dynasty | Nemanjić |

| Father | Stefan Uroš I |

| Mother | Helen of Anjou |

| Religion | Serbian Orthodox |

Dragutin abandoned Uroš I's centralizing policy and ceded large territories to his mother in appanage. After a riding accident, he abdicated in favor of his brother, Milutin in 1282, but he retained the northern regions of Serbia along the Hungarian border. Two years later, his brother-in-law, Ladislaus IV of Hungary, granted him three banates—Mačva (or Sirmia ulterior), Usora and Soli—to him. He was the first Serbian monarch to rule Belgrade. With his brother's support, he also occupied the Banate of Braničevo in 1284 or 1285.

Dragutin was in theory a vassal both to his brother (for his Serbian territories), and to the Hungarian monarchs (for the four banates), but he actually ruled his realm as an independent ruler from the 1290s. His conflicts with Milutin developed into an open war in 1301 and he made frequent raids against the neighboring Hungarian lords from 1307. Most of the Serbian noblemen supported Dragutin, but he was forced to make peace with Milutin after Milutin's mercenaries routed him in 1311 or 1312. Before his death, he entered into a monastery and died as the monk Teokist. In the list of Serbian saints, Dragutin is venerated on 12 November or 30 October (Old Style and New Style dates).

Early life

Dragutin was the eldest son of King Stefan Uroš I of Serbia and Helen of Anjou.[1][2] The place and date of his birth is unknown.[3] In 1264, the monk Domentijan recorded that the "fourth generation" of the descendants of Stefan Nemanja was already old enough "to ride a horse and carry a warrior's lance".[3] For Domentijan obviously referred to Dragutin, historian Miodrag Purković concluded that Dragutin must have been twenty at that time and dated Dragutin's birth to around 1244.[4]

Neither is known the date of Dragutin's marriage with Catherine of Hungary.[1] His father and her grandfather, Béla IV of Hungary, most probably decided the marriage during the peace negotiations that followed Uroš I's invasion of Mačva in 1268,[1][2][5][6] but an earlier date cannot be excluded.[3] Mačva was a Hungarian border province to the north of Serbia which had been governed by Béla IV's daughter, Anna, on behalf of her minor son, Béla.[1] Uroš I launched a plundering raid against the province, but he was captured and forced to seek a reconciliation.[1] Catherine's father, Stephen V, had been bearing the title of "younger king" as his father's co-ruler and heir and the same title was bestowed on Dragutin in token of his exclusive right to inherit Serbia from his father.[7][8] The Peace of Pressburg between Stephen V and King Ottokar II of Bohemia is the first extant document which mentioned Dragutin as younger king.[6]

Decades later, Danilo II, Archbishop of Serbia, recorded that Dragutin's Hungarian in-laws also expected that Uroš would cede parts of his realm to Dragutin to allow him to rule them independently.[7][8] The peace agreement may have explicitly prescribed the division of Serbia between Uroš I and Dragutin, according to Aleksandar Krstić and other historians.[6][7][8] After spending years to strengthen central government, Uroš was reluctant to divide his kingdom with his son.[7] Dragutin and his wife were living in his father's court when a Byzantine envoy visited Serbia in the late 1260s.[9]

Dragutin rose up against his father in 1276.[9] Whether he only wanted to persuade his father to share power with him, or he was afraid of being disinherited in favor of his younger brother, Milutin, cannot be decided.[9] Dragutin's brother-in-law, Ladislaus IV of Hungary, sent Hungarian and Cuman troops to Serbia to assist him.[10] Dragutin routed his father near Gacko in the autumn of 1276.[10] Uroš abdicated without further resistance and entered the Sopoćani Monastery where he died a year later.[9]

Reign

Serbia

The Archbishop of Serbia, Joanikije I, abdicated after the fall of Uroš I.[9] He may have expressed his protest against Dragutin's usurpation in this way, or he may have been forced to resign because of his close relationship with the dethroned monarch.[9] Soon after ascending the throne, Dragutin, gave large parts of Serbia—including Zeta, Trebinje and other coastal territories, and Plav—to his mother in appanage.[11] Helen's appanage included the core territories of the former Kingdom of Duklja and developed into a province of the heirs to the Serbian throne after her death.[8] Milutin accompanied their mother to her realm and settled in Shkodër.[11]

Serbia's relationship with the Republic of Ragusa had been tense during the last years of Uroš I's reign, although his wife secretly supported the republic.[1] Dragutin achieved a reconciliation shortly after he mounted the throne.[8] Charles I of Anjou, King of Sicily, wanted to involve Dragutin into a coalition against the Byzantine Empire.[12] The two kings exchanged letters about this issue in 1279.[13]

Dragutin fell off his horse and broke his leg in early 1282.[12] His injury was so severe that a council was convoked to Deževo to make decisions about the government of Serbia.[11] At the council, Dragutin abdicated in favor of Milutin,[8] but the circumstances of his abdications are uncertain.[14][15] Decades later, Dragutin remembered that he had already come into conflict with Milutin, but he had ceded the government to Milutin only provisionally, until he recovered.[14] Archbishop Danilo II wrote that Dragutin abdicated because he regarded the riding accident as God's punishment for his acts against his father, but the Archbishop also referred to unspecified "serious troubles" that contributed to Dragutin's decision.[14] The Byzantine historian, George Pachymeres, was informed that Dragutin's abdication had been definitive, but Pachymeres also mentioned an agreement between the two brothers that secured the right of Dragutin's (unnamed) son to succeed Milutin.[14]

Sirmia ulterior

Inscriptions on frescos and diplomatic correspondence evidence that Dragutin was styled king after his abdication, but Milutin's supreme position is evident.[16] Dragutin continued to style himself as king in his royal charters and coins.[6] Dragutin and Milutin wore royal insignia on a fresco in the St. Achillios church, which was Dragutin's endowment near Arilje, but Dragutin is depicted with fewer royal emblems.[6] Actually, Serbia was divided between Dragutin and Milutin at Dragutin's abdication, with Dragutin retaining the northern region along the Hungarian border, including the recently opened silver mine at Rudnik.[15] He also held territories in western Serbia on the river Lim,[15] thus he was his brother's most powerful vassal.[17] Ladislaus IV of Hungary granted Mačva, Usora and Soli to Dragutin in the second half of 1284.[16] The same territories had been held in appanage by relatives of the Hungarian monarchs, most recently by Dragutin's mother-in-law, Elizabeth the Cuman, and Dragutin continued to rule them as a Hungarian vassal.[18] Mačva was also known as Sirmia ulterior, hence Dragutin's contemporaries often styled him as "King of Srem".[17] He took up his seat at Debrc on the Sava, but he also regularly stayed in Belgrade, thus he was the first Serbian monarch to rule this town.[17]

Dragutin administered his realm independently of his brother.[19] He supported the Franciscans' missions in Bosnia and allowed the establishment of a Catholic see in Belgrade.[20] Two Cuman or Bulgarian warlords, Darman and Kudelin, had seized a former Hungarian banate, Banate of Braničevo.[20][21] Dragutin invaded Braničevo with Hungarian assistance in 1284 or 1285, but could not defeat them.[20][22] Darman and Kudelin hired Cuman and Tatar troops and started raiding Dragutin's realm.[23] Dragutin sought assistance from Milutin and the two brothers met in Mačkovac.[24] After they joined their forces and defeated Darman and Kudelin, Dragutin seized Braničevo in 1291 or 1292.[17][20] The new Hungarian monarch, Andrew III, also supported their military action, but Andrew's weak position in Hungary enabled Dragutin to strengthen his independence.[17]

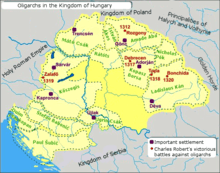

Dragutin's sister-in-law, Mary, had laid claim to Hungary after the death of her brother, Ladislaus IV.[25] Dragutin was allegedly willing to support her and her son, Charles Martel of Anjou.[26] Charles Martel, who regarded himself the lawful king of Hungary, granted Slavonia to Dragutin's son, Vladislav, in 1292,[26] but most Hungarian noblemen and prelates remained loyal to Andrew III.[25] Dragutin also sought a reconciliation with Andrew and Vladislav married Constance, the granddaughter of Andrew's uncle, Albertino Morosini in 1293.[27] Dragutin took advantage of the disintegration of Hungary during the last decade of the 13th century and became one of the dozen "oligarchs" (or powerful lords) who ruled vast territories independently of the monarch.[28][29]

Dragutin supported his brother's attacks against the Byzantine territories in Macedonia in the 1290s.[19] After Milutin made peace with the Byzantine Empire in 1299, dozens of Serbian noblemen, who had benefitted from the war, moved to Dragutin's realm.[30] Tensions between the two brothers rapidly grew, most probably because Milutin wanted to secure the succession in Serbia to his own sons.[30][31] In 1301, open war broke out and Milutin occupied Rudnik from Dragutin.[32] According to Ragusan reports, a peace treaty was made in late 1302, but Dragutin's troops or allies pillaged Milutin's silver mines at Brskovo already in 1303.[33][26] The armed conflict lasted for more than a decade, but its details are unknown.[32][33] The parties allegedly avoided fighting in pitched battles and Dragutin could retain his realm almost intact, although income from the silver mines enabled Milutin to hire mercenaries.[33]

Charles Martel's son, Charles Robert had come to Hungary to assert his claim to the throne in 1300.[34] His grandfather, Charles II of Naples, listed Dragutin and Dragutin's wife among Charles Robert's principal supporters.[34] Between the summer of 1301 and May 1304, Charles Robert spent much time in the powerful Ugrin Csák's domains which were located to the north of Dragutin's realm, implying that Charles Robert's relationship with Dragutin was cordial.[35] For unknown reasons, Dragutin's troops pillaged Csák's domains in 1307, but Csák made a counter-attack and defeated Dragutin's army before 13 October 1307.[36] Dragutin made an alliance with Charles Robert's opponent, Ladislaus Kán, who ruled Transylvania in the 1300s.[36] Dragutin's Orthodox son married Kán's daughter, for which the papal legate, Gentile Portino da Montefiore, excommunicated Kán at the end of 1309.[37] Historian Alexandar Krstić proposes that Dragutin wanted to secure the Hungarian throne for his elder son, Vladislav, and the Serbian throne for his younger son, Urošica.[38] Records of the destructions that Dragutin and his troops made in Valkó and Szerém Counties most probably refer to Dragutin's frequent raids against Ugrin Csák's territories in 1309 and 1310.[39] He also seized properties of the Archbishopric of Kalocsa, which prevented the newly elected Archbishop Demetrius from visiting Rome before the end of 1312.[38]

.jpg)

His conflict with Charles Robert forced him to fight on two fronts, but he could continue the war against his brother after Serbian noblemen rose up against Milutin in the early 1310s.[31][38] The Serbian prelates remained loyal to Milutin and assisted him to hire Tatar, Jassic and Turkish mercenaries.[33][40] After Milutin inflicted a decisive defeat on Dragutin in late 1311 or in 1312, the prelates mediated a peace treaty between them most probably in 1312.[41] Dragutin had to acknowledge his brother as the lawful king, but his Serbian appanage (including the silver mine at Rubnik) was fully restored to him.[42][43] Dragutin sent reinforcements to help his brother's fight against the powerful Ban of Croatia, Mladen II Šubić of Bribir, in 1313.[42][44] According to Krstić, Dragutin obviously made a peace treaty with Charles Robert in Sremska Mitrovica in February 1314.[44] In 1314 or 1316, Dragutin signed his brother's charter of grant to the Banjska Monastery as "the former king".[43]

Dragutin became a monk and adopted the name of Teoctist shortly before his death.[44] While he was dying, he stated that he could not be venerated as a saint, according to Archbishop Danilo II's biography.[44] He died on 12 March 1316.[44] He was buried in the Đurđevi Stupovi Monastery.[44] He is regarded as the second founder of the monastery, which had been built by his great-grandfather, Stephen Nemanja.[44][45]

See also

- History of Serbia

- Srem

References

- Fine 1994, p. 203.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 48.

- Purković 1951, p. 546.

- Purković 1951, pp. 546–547.

- Krstić 2016, pp. 33–34.

- Gál 2013, p. 484.

- Krstić 2016, p. 34.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 49.

- Fine 1994, p. 204.

- Vásáry 2005, p. 100.

- Fine 1994, p. 217.

- Krstić 2016, p. 35.

- Setton 1975, p. 130.

- Krstić 2016, p. 36.

- Fine 1994, p. 218.

- Krstić 2016, p. 37.

- Krstić 2016, p. 38.

- Krstić 2016, pp. 37–38.

- Fine 1994, p. 221.

- Fine 1994, p. 220.

- Vásáry 2005, pp. 88, 104.

- Vásáry 2005, p. 107.

- Vásáry 2005, p. 104.

- Vásáry 2005, p. 105.

- Engel 2001, p. 110.

- Krstić 2016, p. 39.

- Krstić 2016, pp. 39–40.

- Engel 2001, pp. 124–125.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 50.

- Fine 1994, pp. 255–256.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 52.

- Krstić 2016, p. 40.

- Fine 1994, p. 257.

- Krstić 2016, p. 42.

- Krstić 2016, pp. 42–43.

- Krstić 2016, p. 43.

- Krstić 2016, pp. 43–44.

- Krstić 2016, p. 45.

- Krstić 2016, pp. 44–45.

- Vásáry 2005, p. 110.

- Krstić 2016, pp. 45–46.

- Fine 1994, p. 258.

- Krstić 2016, p. 46.

- Krstić 2016, p. 47.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 60.

Sources

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-20471-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Engel, Pál (2001). The Realm of St Stephen: A History of Medieval Hungary, 895–1526. I.B. Tauris Publishers. ISBN 1-86064-061-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fine, John V. A. (1994). The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-08260-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gál, Judit (2013). "IV. Béla és I. Uroš szerb uralkodó kapcsolata [The relationship of Béla IV and the Serbian ruler, Uroš I]". Századok (in Hungarian). 147 (2): 471–499. ISSN 0039-8098.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Krstić, Aleksandar (2016). "The rival and the vassal of Charles Robert of Anjou: King Vladislav II Nemanjić". Banatica. 26 (II): 33–51. ISSN 1222-0612.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Purković, Miodrag Al. (1951). "Two Notes on Mediæval Serbian History". The Slavonic and East European Review. 29 (73): 545–549. ISSN 0037-6795.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Setton, Kenneth M. (1976). The Papacy and the Levant (1204–1571), Volume I: The Thirteenth and the Fourteenth Centuries. The American Philosophical Society. ISBN 0-87169-114-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vásáry, István (2005). Cumans and Tatars: Oriental Military in the Pre-Ottoman Balkans, 1185–1365. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-83756-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Dinić, Mihailo (1951). "Област краља Драгутина после Дежева [King Dragutin's territory after Deževo]". Glas (203): 61–82.

- Fajfrić, Željko (2000) [1998], Sveta loza Stefana Nemanje, Belgrade: Tehnologije, izdavastvo, agencija Janus

- Kosta N. Kostić (1899). "Kralj Stefan Dragutin". (Public Domain)

- Lazarević, Dragana (1990). "Teritorija kralja Dragutina" (PDF). Glasnik. Međuopštinski Istorijski Arhiv Valjeva.

- Ostrogorsky, George (1956). History of the Byzantine State. Basil Blackwell.

- Stanojević, Stanoje (1936). Kralj Dragutin. Belgrade: Geca Kon.

- Zarković, B. (2009). "Prilog kralja Dragutina manastiru Hilandaru" (PDF). Baština (27): 115–126.

Stefan Dragutin Died: 12 March 1316 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Uroš I |

King of Serbia 1276–1282 |

Succeeded by Milutin |

| Preceded by new title |

King of Syrmia 1282–1316 |

Succeeded by Vladislav |