Stanford in the Vale

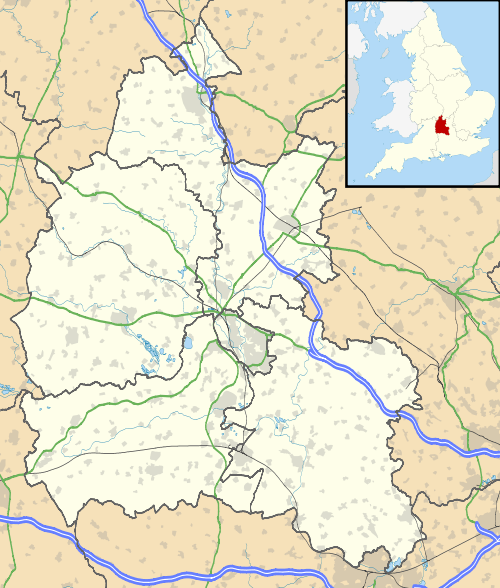

Stanford in the Vale is a village and civil parish in the Vale of White Horse about 3 1⁄2 miles (5.6 km) south-east of Faringdon and 5 miles (8 km) northwest of Wantage.[1] It is part of the historic county of Berkshire, however since the 1974, it has been administered as a part of Oxfordshire. The 2011 Census recorded the parish's population 2,093.[2]

| Stanford in the Vale | |

|---|---|

St Denys' parish church | |

Stanford in the Vale Location within Oxfordshire | |

| Population | 2,093 (2011 Census) |

| OS grid reference | SU342935 |

| Civil parish |

|

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Faringdon |

| Postcode district | SN7 |

| Dialling code | 01367 |

| Police | Thames Valley |

| Fire | Oxfordshire |

| Ambulance | South Central |

| UK Parliament | |

| Website | Stanford in the Vale Parish Council |

Geography

Stanford is a village with a clustered centre just north of the nascent River Ock, which is a tributary of the River Thames and flows from west to east through the parish. The parish is about 2 miles (3 km) wide north – south but extends for more than 4 1⁄3 miles (7 km) east – west along the course of the Ock and its tributaries. One tributary, Stutfield Brook, forms the southeast boundary of the parish. Another, Frogmore Brook, forms part of the northern boundary. The western boundary follows the edges of present and former fields.

Stanford village is built on soil-clad Corallian Limestone, which in patches comes close to the surface through erosion. The village is on the A417 road that links Faringdon and Wantage. All outlying parts of the parish are used for farming, interspersed with woodland and other land-intensive industries, with the exception of Bow, a hamlet just north of the village and almost contiguous with the village's core.

Archaeology

On Bowling Green Farm at the western end of the parish, about 1 mile (1.6 km) east of Faringdon, are remains of what was probably a Roman estate. Along a ridge of Corallian Limestone was a village street more than 1⁄4 mile (400 m) long.[3] Below it in the valley there may have been a large Roman villa and bath-house.[4] Evidence exists of Roman fields and scattered outbuildings surrounding the village and villa.[3]

In the east end of the parish, about 700 yards (640 m) east of Stanford Park Farm, is a rectangular moated enclosure beside Stutfield Brook at a place called Stanford Park Island. Exploratory excavations in the early 1960s revealed no evidence of habitation.[5]

Toponym

The toponym "Stanford" is derived from the Old English for a "stone ford" across the Ock.[6][7]

Manor

In the reign of Edward the Confessor in the middle of the 11th century, one Siward Barn held the manor of Stanford. The Domesday Book of 1086 records that after the Norman Conquest of England, the Norman nobleman Henry de Ferrers held it. It was made part of the Honour of Tutbury, and remained with the de Ferrers family until the 1260s, when Robert de Ferrers, 6th Earl of Derby was defeated in the Second Barons' War and forfeited his estates in 1266.[8] The Dictum of Kenilworth issued that October allowed him to reclaim his lands by paying a premium, which he did in 1269.

However, by 1276 Stanford had been granted to Gilbert de Clare, 7th Earl of Gloucester. When his successor Gilbert de Clare, 8th Earl of Gloucester was killed at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314, Stanford passed to Eleanor de Clare, wife of Hugh Despenser the Younger. As a result of the rebellions and executions of Hugh and his father Hugh le Despenser, 1st Earl of Winchester in 1326, and their descendant Thomas le Despenser, 1st Earl of Gloucester in 1400, all Despenser lands were twice forfeited to the Crown. But after each forfeiture, Stanford was among the estates restored to the rebel's widow. In the early 15th century Stanford was among the manors that passed by the marriage of Isabel le Despenser, Countess of Worcester to Richard de Beauchamp, 13th Earl of Warwick. In 1474 Anne Beauchamp, 16th Countess of Warwick conferred all her estates on her two daughters. Stanford was among those that she passed to Anne Neville, Queen Consort of King Richard III. But in 1485 Richard was defeated and killed at the Battle of Bosworth Field and her estates were forfeit. In 1489 the all Countess's estates, including Stanford, were restored to her, but she conveyed them to the victorious King Henry VII.[8]

In the 16th century the manor of Stanford passed through notable local landholding families including those of Fettiplace and Knollys. When Francis Knollys died in 1596, the manor of Stanford was divided between his granddaughters Elizabeth and Lettice. Around the turn of the 17th century Elizabeth Knollys became married to Henry Willoughby of Risley, Derbyshire, who in 1611 was created 1st Baronet. Their daughter Anne was married to Sir Thomas Aston, 1st Baronet, and their half of Stanford remained in their family until Sir Thomas Aston, 4th Baronet died in 1744. Meanwhile, Lettice Knollys was married to William Paget, 4th Baron Paget, and her half of the manor of Stanford remained with his heirs until 1715, when Henry Paget, 1st Earl of Uxbridge conveyed it to Peter Walter and John Morse. By the end of the 18th century an Edward Loveden Loveden bought and reunited the two halves of the manor.[8]

The present manor house was built in the 16th century and remodelled in a Georgian style in the 18th.[9] It is a Grade II* listed building.[10]

Churches and chapel

Church of England

The oldest parts of the Church of England parish church of Saint Denys are its late 12th-century south and north doorways. The west tower was built late in the 13th century, but its height was increased later. The chancel is Decorated Gothic. Later are the 14th-century north and south aisles, Perpendicular Gothic clerestory and south and north porches. Remnants of 14th-century stained glass survive in the east and south windows of the chancel.[11] The pulpit and baptismal font are Jacobean. The pulpit is wooden; the font is stone encased with wooden panels and cover. The church is a Grade I listed building[12]

The tower has a ring of eight bells. Abraham I Rudhall of Gloucester cast the third, fifth, seventh and tenor bells in 1700. Abel Rudhall cast the fourth bell in 1753. Mears and Stainbank of the Whitechapel Bell Foundry cast the treble and second bells in 1891.[13]

St Denys' parish is part of the Benefice of Stanford in the Vale with Goosey and Hatford.[14]

United Reformed

There is a United Reformed Church in Chapel Lane.[15] It was formerly a Congregational chapel.[8] It is no longer in use.

Methodist

Stanford had a Primitive Methodist chapel.[8] It is now a private house.

Economic and social history

In 1230 King Henry III granted William de Ferrers, 4th Earl of Derby and the men of Stanford the rights to hold a weekly market in the village and an annual three-day fair on the eve, feast and morrow of St Denis,[8] which is 8–10 October. Stanford's market and fair faced competition with those of other villages in the area including Baulking, East Hendred, Hinton Waldrist, Kingston Lisle and Shrivenham.[16]

In the English Civil War there were clashes a few miles to the north, at Faringdon and Radcot (a strategic crossing of the Thames), 1644 and 1645. According to oral history, Parliamentarian cavalry was billeted in the village.

On 21 August 2005 a fire badly damaged a row of five 16th-, 17th- and 18th-century thatched cottages[17] beside Church Green. The fire was seen at 1:30 a.m. by an off-duty soldier from Dalton Barracks, who rescued nine people from the cottages.[18] All five cottages have since been restored.[19]

Economy and amenities

.jpg)

Stanford has a primary school,[20] a pre-school, two village greens, a post office, other shops and businesses, and a number of clubs and societies. The village has one public house, the Horse and Jockey.[21] It had two other pubs, the Red Lion and the Anchor, each of which has been converted into a private house.[22][23]

The 2011 Census found that the largest category of occupation in Stanford in the Vale is that of professions (151 of 1041 workers). In the more subdivided categorization of workers into industries, the largest was that of motor-related industries, including trade of motor vehicles (151 of 1041 workers). This was followed, in order, by human health and social work, professional, scientific and technical activities and by education as the other occupations. With between 88 and 95 workers, construction and manufacturing were industries in which other villagers at the date of that census tended to work.

In the parish various grades of sand and gravel are quarried. However, only two people were employed in mining and quarrying: 0.2% of the working population. The gravel pit in the near northwest of the parish is dormant.

Transport

Bus routes 67 and 67C link Stanford with Faringdon and Wantage six days a week. There is no service on Sundays or bank holidays. They are both operated by Thames Travel.

Notable people

The poet Pam Ayres was born in Stanford in 1947.[24]

The English biographer Winifred Gérin lived in Stanford in the 1970s.

President and Life Member of the Berks & Bucks Football Association and North Berks Football League, W.J. Gosling, died in the village on June 7th 2020 having lived in the village for over sixty years.

Twinning

The village has been twinned with Saint-Germain-du-Corbéis in Lower Normandy, France since 1989.

Neighbouring settlements

References

- Grid Reference Finder

- "Area: Stanford in the Vale (Parish): Key Figures for 2011 Census: Key Statistics". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- Salway 1999, p. 17.

- Cook, Guttmann & Mudd 2004, p. 186.

- Sturdy & Case 1963, p. 92.

- Arkell 1942, p. 6.

- Lambrick 1969, p. 83.

- Page & Ditchfield 1924, pp. 478–485.

- Pevsner 1966, p. 227.

- Historic England. "The Manor House and Manor Cottage (Grade II*) (1368451)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- Pevsner 1966, p. 226.

- Historic England. "Church of St Denys (Grade I) (1048607)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- Davies, Peter (20 December 2012). "Stanford in the Vale S Denys". Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers. Central Council for Church Bell Ringers. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- Archbishops' Council. "Benefice of Stanford in the Vale with Goosey and Hatford". A Church Near You. Church of England. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- "Stanford-in-the-Vale". Oxfordshire Churches & Chapels. Brian Curtis. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- Mellor 1994, p. 148.

- Historic England. "3–7, Church Green (Grade II) (1182846)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- "Soldier a hero at cottages blaze". BBC. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- "Church Green Cottage Fire – 21/8/2005". Stanford in the Vale.

- Stanford in the Vale Primary School

- The Horse and Jockey

- Historic England. "Former Red Lion public house (Grade II) (1048578)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- Hudson, Laura (7 November 2012). "Application No. P12/V0291/COU" (PDF). Vale of White Horse District Council. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- "About Pam". Pam Ayres. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

Sources

- Arkell, WJ (1942). "Place-names and Topography — Upper Thames Country" (PDF). Oxoniensia. Oxford Architectural and Historical Society. VII: 1–23. ISSN 0308-5562.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ayres, Pam (2011). The Necessary Aptitude. A Memoir. London: Ebury Press. ISBN 0091940486.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cook, J; Guttmann, EBA; Mudd, A (2004). "Excavations of an Iron Age Site at Coxwell Road, Faringdon" (PDF). Oxoniensia. Oxfordshire Architectural and Historical Society. LXIX: 181–286. ISSN 0308-5562.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lambrick, Gabrielle (1969). "Some Old Roads of North Berkshire" (PDF). Oxoniensia. Oxford Architectural and Historical Society. XXXIV: 78–93. ISSN 0308-5562.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mellor, Maureen (1994). "A Synthesis of Middle and Late Saxon, Medieval and Early Post-Medieval Pottery in the Oxford Region" (PDF). Oxoniensia. Oxfordshire Architectural and Historical Society. LIX. ISSN 0308-5562.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Page, W.H.; Ditchfield, P.H., eds. (1924). A History of the County of Berkshire. Victoria County History. 4. assisted by John Hautenville Cope. London: The St Katherine Press. pp. 478–485.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (1966). Berkshire. The Buildings of England. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. pp. 226–227.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Salway, Peter (1999). "Roman Oxfordshire" (PDF). Oxoniensia. Oxfordshire Architectural and Historical Society. LXIV: 1–22. ISSN 0308-5562.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sturdy, David; Case, Humphrey (1963). "Archaeological Notes" (PDF). Oxoniensia. Oxford Architectural and Historical Society. XXVIII: 87–92. ISSN 0308-5562.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stanford in the Vale. |