St Andrew's Church, Wroxeter

St Andrew's Church is a redundant Church of England parish church in the village of Wroxeter, Shropshire, England. It is recorded in the National Heritage List for England as a designated Grade I listed building,[1] and is under the care of the Churches Conservation Trust.[2] Both the village of Wroxeter and the church are in the southwest corner of the former Roman town of Viroconium.[3]

| St Andrew's Church, Wroxeter | |

|---|---|

St Andrew's Church, Wroxeter, from the southwest | |

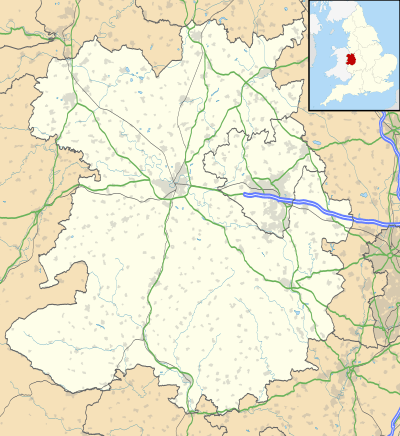

St Andrew's Church, Wroxeter Location in Shropshire | |

| 52.6701°N 2.6472°W | |

| OS grid reference | SJ 563 082 |

| Location | Wroxeter, Shropshire |

| Country | England |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Website | Churches Conservation Trust |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Redundant |

| Architectural type | Church |

| Style | Anglo-Saxon, Norman, Gothic |

| Closed | 1980 |

| Specifications | |

| Materials | Sandstone, tiled roofs |

History

The earliest parts of the church are Anglo-Saxon but the precise date of its foundation in uncertain. There is strong circumstantial evidence that a church was built in the area of the Roman bath in the 5th or 6th century.[4] A preaching cross was erected in the churchyard in the 8th century.[5] It is thought that the oldest existing fabric in the present church dates from the 8th or 9th century.[4][5] This consists of large stones which came from the public buildings of the Roman town. By the time of the Domesday Book in 1086 the church had a college of four priests.

In 1155 William FitzAlan, Lord of Oswestry, who then held the advowson, gave the church to Haughmond Abbey.[6] At that time it was a portionary church, i.e. a church served by a group of priests who took shares in the income but did not form a corporate entity, as would be the case in a collegiate church. FitzAlan declared his intention of increasing the number of canons to a "full convent", perhaps meaning 12, possibly in order to create a chantry for the FitzAlan family. Haughmond Abbey was to be the FitzAlan burial place for several centuries but the chapter of St Andrew's church was never expanded on the scale he envisaged. However, the building itself was extended and enhanced. In about 1190 a large chancel was built and in about 1210 a south aisle was added. A chantry chapel dedicated to Saint Mary was built and the nave was lengthened westwards. In about 1470 the lower part of the tower was built.

After the English Reformation the interior of the church was damaged, the wall paintings were covered with whitewash and wooden statues and fittings were burnt. The upper part of the tower was added in 1555, incorporating material from Haughmond Abbey. By the middle of the 18th century the population of the village was declining, and the church was becoming unstable because of the inadequate medieval foundations.[5] In 1763 the south aisle and chapel were demolished, and part of the chapel was converted into a vestry.[3] The church was restored in about 1863, and in 1890 a porch was added and the tower was restored.[1] By the end of the 19th century most of the local people had moved away.[5] The church was declared redundant on 1 December 1980, and was vested in the Churches Conservation Trust on 18 May 1987.[7]

Architecture

Exterior

St Andrew's is built of sandstone with tiled roofs. It has a nave, south porch, chancel, south vestry, and west tower. The tower is divided by string courses into three stages. It has a plinth, diagonal buttresses, a battlemented parapet with gargoyles, and a pyramidal cap with a weathervane. On its northeast is an octagonal stair turret, also with a pyramidal cap. In the upper stages on the north, west and east fronts are carved fragments which are said to have come from Haughmond Abbey; these include canopied niches, some containing sculpted figures, and ceiling bosses. In the bottom stage is a three-light west window, there are rectangular openings in the middle stage, and the top stage contains two-light louvred bell openings. The north wall of the nave is Anglo-Saxon and contains blocks from former Roman buildings. These blocks have Lewis holes.[1] This wall has a triple lancet window and a three-light arched window.[3] In the south wall are two-three light windows and a porch containing a doorway. The porch has a parapeted gabled double lancet window, and a carved frieze. Set into the top of the south wall is a fragment of a 7th-century Anglo-Saxon cross-shaft. On each side of this is a carved block of similar date, one depicting a beast and the other a bird. The chancel also incorporates some re-used Roman masonry in its north wall, which contains two narrow round-headed windows and a triple lancet window. In the south wall is a blocked Norman priest's doorway. The east window has five lights, and around it are portions of blocked former windows. The vestry has two square windows, one on each side of a round-arched doorway.[1]

The sandstone churchyard gate piers were made in the 19th century re-using Roman masonry.[8] The square bases came from farm buildings, the shafts of the columns from the Roman baths, and the capitals from an unknown source.[3] They have a pair of cast iron gates, and are listed Grade II.[8]

Interior

In the east wall of the chancel is an aumbry and an Easter Sepulchre with ballflower ornamentation.[1] The sepulchre contains traces of a wall-painting depicting Christ in Glory.[3] The church has a west gallery. On the walls of the church are painted benefactors' boards and Royal coats of arms. The nave contains box pews. The font is large and round, and was constructed from the base of a former Roman column.[1] Behind the font is a 13th-century iron-bound oak chest.[5] The carved wooden pulpit has five sides.[1] A wooden pedimented reredos hangs on north wall of the nave and is painted with the Lord's prayer, the Ten Commandments and the Creed. The stained glass in the chancel was designed in 1860 by E. Baillie and depicts the twelve apostles and biblical scenes. In the north side of the nave are windows depicting saints, made in 1920 by Morris & Co.. The latter workshop also made the two-light window at the west end, depicting St Andrew and St George and the motto "AD.MAJOREM - DEI GLORIAM", as a First World War memorial; nearby are two brass plaques listing the parish dead of both World Wars. One of the First World War dead, Captain C W Wolseley-Jenkins, also has an individual memorial tablet on the east end's north wall.[9]

The largest memorial in the church is an alabaster tomb-chest carrying the effigies of Thomas Bromley, former Justice of the Queen's Bench, who died in 1555, and his wife. Another tomb-chest carrying effigies is that of Sir Richard Newport, who died in 1570, and his wife Margaret, the daughter of Thomas Bromley. John Barker (rendered as Berker) of Haughmond Abbey and his wife, Margaret Newport, both of whom died in 1618,[3] have another tomb chest, inscribed with the detail: "the said John Barker being in good perfect health at the decease of the said Margaret, fell ill the day following and deceased, leaving no issue behind."[10] The Barker family were Shrewsbury merchants and several represented the town in Parliament. They were exceptionally wealthy, and able to marry into the upper strata of the landed gentry, partly because of a bequest from Rowland Hill, reputedly the first Protestant to become Lord Mayor of London. On the wall of the chancel is a marble memorial to Francis Newport, 1st Earl of Bradford, who died in 1708.[1] This has been attributed to Grinling Gibbons.[3]

The tower has a ring of six bells. The oldest is dated 1598 and was cast by Henry Oldfield II of Nottingham. Three of the bells were cast in the Clibery foundry in Wellington in the 17th century. The newest bell is by John Warner and Sons of London and is dated 1877.[11] The two-manual organ is in the west gallery and was made by Brindley of Sheffield in 1861.[12]

- The Bromley tomb

- Tomb of Thomas Bromley and Isabel Lyster.

- Effigies of Thomas Bromley and his wife, Isabel Lyster.

- Margaret, daughter of Thomas Bromley and his wife, Isabel Lyster, portrayed on the Bromley tomb.

Arms of Thomas Bromley.

Arms of Thomas Bromley.- Arms of Thomas Bromley impaled with those of his wife.

- Effigy of Richard Newport, St Andrew's church, Wroxeter, Shropshire.

See also

References

- Historic England, "Church of St Andrew, Wroxeter And Uppington (1224008)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 14 April 2013

- St Andrew's Church, Wroxeter, Shropshire, Churches Conservation Trust, retrieved 17 October 2016

- Newman, John; Pevsner, Nikolaus (2006) [1958], Shropshire, The Buildings of England (revised ed.), New Haven and London: Yale University Press, pp. 718–720, ISBN 0-300-12083-4

- White, Roger; Dalwood, Hal, Archaeological assessment of Wroxeter, Shropshire, York: Department of Archaeology, University of York

- White, Roger (2001), St Andrew's Church, Wroxeter: Information for teachers, London: Churches Conservation Trust

- A T Gaydon, R B Pugh (Editors), M J Angold, G C Baugh, Marjorie M Chibnall, D C Cox, Revd D T W Price, Margaret Tomlinson, B S Trinder (1973), "Houses of Augustinian canons: Abbey of Haughmond", A History of the County of Shropshire: Volume 2, Institute of Historical Research, retrieved 12 March 2014CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Diocese of Lichfield: All Schemes (PDF), Church Commissioners/Statistics, Church of England, 2011, p. 7, retrieved 7 April 2011

- Historic England, "Churchyard and gates, gate piers and approximately 3 metres of flanking walls approximately 10 metres to west of west tower of Church of St Andrew (1224775)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 1 October 2013

- Francis, Peter (2013). Shropshire War Memorials, Sites of Remembrance. YouCaxton. p. 124. ISBN 978-1-909644-11-3.

- Hyde, Patricia (1981), Hasler, P. W. (ed.), BARKER, John II (1579-1618), of Haughmond Abbey, Salop., History of the Parliament, 1558–1603: Members, London: History of Parliament Online, retrieved 12 August 2016

- Wroxeter, St Andrew, Shropshire Association Towers, retrieved 27 September 2010

- Shropshire, Wroxeter, St. Andrew (N04723), British Institute of Organ Studies, retrieved 27 September 2010

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to St Andrew's Church, Wroxeter. |