Squamacula

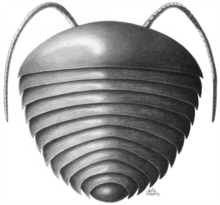

Squamacula is an extinct arthropod from the Cambrian Series 2, the type species S. clypeata was described in 1997 from the Chengjiang biota. At the time of description there were only two known specimens of S. clypeata, but now there are at least six known specimens.[2] In 2012 a second species S. buckorum was described from the Emu Bay Shale of Australia.[3]

| Squamacula | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reconstruction | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| (unranked): | †Artiopoda |

| Genus: | †Squamacula Hou and Bergström, 1997 |

| Type species | |

| Squamacula clypeata Hou and Bergström, 1997[1] | |

| Other species | |

|

Squamacula buckorum Paterson et al. 2012 | |

Etymology

The genus Squamacula is derived from the Latin word squama, meaning scale, and the diminutive suffix -culus, indicating that the animal is relatively small. The species clypeata is derived from the Latin word clypeatus, meaning shield-shaped. It was named this in reference to its shield-like outline.[1]

Description

Squamacula clypeata is flattened (dorsoventrally). It has 11 segments in total: the cephalon (the head), nine thoracic tergites (each of which covers a somite), and one pygidium.[4] It has a doublure, a piece of exoskeleton that covers part of the underside of the animal. Its doublure is, on average, about twice as long as the length of its cephalon. It has been hypothesized that this large doublure could have aided the animal in digging through sediment to find food, as it was thought to have been both a predator of small animals and a scavenger.[4]

Squamacula clypeata has one pair of antennae attached to its cephalon, but no other appendages or auditory or visual structures.[4] No mouth is present in the specimens, but the gut is present, so S. clypeata must have had a mouth, which is thought to have been between the cephalon and doublure on the underside.[4]

Squamacula clypeata has one pair of biramous appendages (an appendage which branches into two) per thoracic tergite.[4] The endopod (inside branch) has seven segments, the first six of which are roughly even in size and shape, with small spines on the underside, and the last of which terminates with a claw and appears to have been used for walking and eating, as the claw could be useful in grabbing hold of and tearing up food.[4] The exopod (outside branch) was not segmented, but flap-like, with setae (bristles) near the tip, which may have been used for both locomotion and respiration.[4]

References

- Hou, Xianguang; Bergström, Jan (1997). Arthropods of the Lower Cambrian Chengjiang fauna, southwest China. Bergström. Oslo: Scandinavian University Press. ISBN 8200376931. OCLC 38305908.

- The Cambrian fossils of Chengjiang, China : the flowering of early animal life. Hou, Xianguang. (Second ed.). Chichester, West Sussex. ISBN 9781118896310. OCLC 970396735.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Paterson, John R.; García-Bellido, Diego C.; Edgecombe, Gregory D. (March 2012). "New artiopodan arthropods from the early Cambrian Emu Bay Shale Konservat-Lagerstätte of South Australia". Journal of Paleontology. 86 (2): 340–357. doi:10.1666/11-077.1. ISSN 0022-3360.

- Zhang, Xingliang; Han, Jian; Zhang, Zhifei; Liu, Huqin; Shu, Degan (2004). "Redescription of the Chengjiang arthropod Squamacula clypeata Hou and Bergström, from the Lower Cambrian, south-west China". Palaeontology. 47 (3): 605–617. doi:10.1111/j.0031-0239.2004.00363.x. ISSN 1475-4983.