Sisyridae

Sisyridae, commonly known as spongeflies or spongillaflies, are a family of winged insects in the order Neuroptera. There are approximately 60 living species described, and several extinct species identified from the fossil record.

| Sisyridae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Sisyra terminalis imago | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Neuroptera |

| Family: | Sisyridae Banks, 1905 |

| Subfamilies | |

|

See text | |

Description

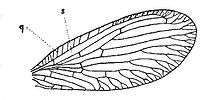

In general appearance, the adults resemble some brown lacewings (Hemerobiidae). The forewings of spongillaflies have a span of 4–10 millimetres. The greyish or brownish wings have few cross veins except in the costal field, and most of these are not forked. The subcostal (Sc) and radial (R1) veins are fused near the wingtip.

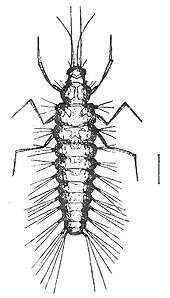

The larvae of spongillaflies look rather bizarre. Similar to those of some osmylids (Osmylidae) at first glance, they have spindly legs on a bulky thorax, long antennae, and flexible, threadlike mouthparts. However, the second and third instars carry seven pairs of jointed, movable tracheal gills beneath their plump abdomen. These gills are possessed by no other extant insect family, and readily distinguish them from osmylid larvae.

Ecology and life cycle

Adult spongillaflies are crepuscular or nocturnal. They are omnivores, sometimes hunting small invertebrates, but mainly scavenging on such animals' carcasses, as well as on pollen and honeydew.

The females deposit their eggs singly or as small clutches on plants that droop over freshwater lakes or slow-moving rivers. A protective web is spun to cover the eggs. When the larvae hatch, they drop down into the water where they develop until pupation. They use their mouthparts to parasitize Spongillidae freshwater sponges (e.g. of the genus Spongilla, hence the name "spongillaflies") and Phylactolaemata freshwater bryozoans by stinging into the host animals' body and sucking out cell contents. The antennae are stouter than they look and are used to aid in locomotion. Development to pupation takes between several weeks and one year.

Spongillafly larvae leave the water and go to hidden places nearby to pupate, choosing locations like beneath rocks or behind tree bark. They spin a cocoon for pupation, but in temperate climates they overwinter in the cocoon as larvae, pupating only the following spring.

Systematics and taxonomy

Spongillaflies were formerly placed in the Osmyloidea, as their closest relatives were held to be the osmylids (Osmylidae) and the Nevrorthidae. This was due to the similar adaptations of the larvae of spongillaflies and osmylids. But this is apparently due to convergent evolution; actually, the spongillaflies seem to be closer to the brown lacewings (Hemerobiidae) than to the osmylids, but even more closely related to the dusty wings (Coniopterygidae). And even though they are not often placed in the superfamily Coniopterygoidea yet, they most likely form a clade with the Coniopterygidae and thus it would seem that the Coniopterygoidea, rather than being an unnecessarily monotypic taxon, is expanded to signify that the spongillaflies and the dusty wings are each other's closest relatives.

A few fossil genera are known, mainly from the Eocene like "Sisyra" amissa which may or may not be the first record of the living genus.[1] The genus Cratosisyrops, from the Aptian Crato Formation, was suggested to be a spongillafly member, but later authors Perkovsky and Makarkin in 2015 noted the fossil lacks details to confidently place it in the family. The oldest members of the family are species in the subfamily Paradoxosisyrinae [2] from Cenomanian Burmese amber and Prosisyrina from Santonian Taimyr amber.[3][4]

The family is currently divided into two subfamilies with the four extant genera and two of the extinct genera placed into Sisyrinae, while five extinct genera are placed into the subfamily Paradoxosisyrinae.[2]

Sisyridae

- †Paradoxosisyrinae

- †Buratina[5]

- †Khobotun[5]

- †Paradoxosisyra

- †Protosiphoniella[5]

- †Sidorchukatia[5]

- Sisyrinae

- Climacia

- †Paleosisyra

- †Prosisyrina

- Sisyborina

- Sisyra

- Sisyrina

References

- Engel, M.S.; Grimaldi D.A. (2007). "The neuropterid fauna of Dominican and Mexican amber (Neuropterida, Megaloptera, Neuroptera)". American Museum Novitates. 3587: 1–58. doi:10.1206/0003-0082(2007)3587[1:TNFODA]2.0.CO;2. hdl:2246/5880.

- Makarkin, V.N. (2016). "Enormously long, siphonate mouthparts of a new, oldest known spongillafly (Neuroptera, Sisyridae) from Burmese amber imply nectarivory or hematophagy". Cretaceous Research. in press: 126–137. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2016.04.007.

- Perkovsky, E.E.; Makarkin, V.N. (2015). "First confirmation of spongillaflies (Neuroptera: Sisyridae) from the Cretaceous". Cretaceous Research. 56: 363–371. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2015.06.003.

- Makarkin, VN; Perkovsky, E.E. (2016). "An interesting new species of Sisyridae (Neuroptera) from the Upper Cretaceous Taimyr amber". Cretaceous Research. 63: 170–176. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2016.03.010.

- Khramov, A; Yan, E.; Kopylov, D. (2019). "Nature's failed experiment: long-proboscid Neuroptera (Sisyridae: Paradoxosisyrinae) from Upper Cretaceous amber of northern Myanmar". Cretaceous Research. 104: Article 104180. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2019.07.010.

- This article draws heavily on the corresponding article in the German-language Wikipedia.

| Wikispecies has information related to Sisyridae |