Spiny dogfish

The spiny dogfish, spurdog, mud shark, or piked dogfish [2] (Squalus acanthias) is one of the best known species of the Squalidae (dogfish) family of sharks, which is part of the Squaliformes order.[3] While these common names may apply to several species, Squalus acanthias is distinguished by having two spines (one anterior to each dorsal fin) and lacks an anal fin. It is found mostly in shallow waters and further offshore in most parts of the world, especially in temperate waters. Spiny dogfish in the northern Pacific Ocean have recently been reevaluated and found to constitute a separate species, now known as "Pacific spiny dogfish", Squalus suckleyi.[4]

| Spiny dogfish Temporal range: Miocene-recent | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Order: | Squaliformes |

| Family: | Squalidae |

| Genus: | Squalus |

| Species: | S. acanthias |

| Binomial name | |

| Squalus acanthias | |

| |

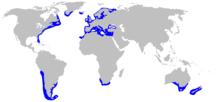

| Range of the spiny dogfish (in blue) | |

Description and behaviour

The spiny dogfish has dorsal fins, no anal fin, and dark green spots along its back. The caudal fin has asymmetrical lobes, forming a heterocercal tail. The species name acanthias refers to the shark's two spines. These are used defensively. If captured, the shark can arch its back to pierce its captor with spines near the dorsal fins that secrete a mild venom into its predator.[5]

This shark is known to hunt in packs that can range up into the thousands. They are aggressive hunters and have a sizable diet that can range from squid, fish, crab, jellyfish, sea cucumber, shrimp and other invertebrates.[6]

Males mature at around 11 years of age, growing to 80–100 cm (31–39 in) in length; females mature in 18–21 years and are slightly larger than males, reaching 98.5–159 cm (38.8–62.6 in).[7] Both sexes are greyish brown in color and are countershaded. Males are identified by a pair of pelvic fins modified as sperm-transfer organs, or "claspers". The male inserts one clasper into the female cloaca during copulation.

Reproduction is aplacental viviparous, which was once called ovoviviparity. Fertilization is internal. The male inserts one clasper into the female oviduct orifice and injects sperm along a groove on the clasper's dorsal section. Immediately following fertilization, the eggs are surrounded by thin shells called "candles" with one candle usually surrounding several eggs. Mating takes place in the winter months with gestation lasting 22–24 months. Litters range between two and eleven, but average six or seven.

Spiny dogfish are bottom-dwellers. They are commonly found at depths of around 50–149 m (160–490 ft), but have been found deeper than 700 m (2,300 ft).[8]

Life span estimates based on analysis of vertebral centra and annuli in the dorsal spines range from 35 to 54 years.[9]

.jpg) Head

Head Jaws

Jaws Upper teeth

Upper teeth Lower teeth

Lower teeth

Commercial use

Spiny dogfish are consumed as human food in Europe, the United States, Canada, New Zealand and Chile. The meat is primarily consumed in England, France, Italy, the Benelux countries, and Germany. The fins and tails are processed into fin needles and are used in less-expensive versions of shark fin soup in Chinese cuisine. In England this and other dogfish are sold in fish-and-chip shops as "huss", and it was historically sold as "rock salmon" until the term was outlawed by consumer legislation. In France it is sold as "small salmon" (saumonette) and in Belgium and Germany it is sold as "sea eel" (zeepaling and Seeaal, respectively). It is also used as fertilizer, liver oil, and pet food. Because of its availability, cartilaginous skull, and manageable size, it is a popular vertebrate dissection specimen in both high schools and universities. Reported catches in 2000–2009 varied between 13,800 tonnes (in 2008) and 31,700 tonnes (in 2000).[10]

Bottom trawlers and sink gillnets are the primary equipment used to harvest spiny dogfish. In Mid-Atlantic and Southern New England fisheries, they are often caught when harvesting larger groundfish, classified as bycatch, and discarded. Recreational fishing accounts for an insignificant portion of the spiny dogfish harvest.[11]

The Cape Cod Commercial Fishermen's Alliance has sponsored an initiative which promotes local, sustainably-caught use of the dogfish in restaurants and fish markets in the Cape Cod area of Massachusetts. The effort is funded by the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration and attempts to get the public to consume under-utilized fish.[12]

Conservation status and management

Once the most abundant shark species in the world, populations of Squalus acanthias have declined significantly. They are classified in the IUCN Red List of threatened species as Vulnerable globally and Critically endangered in the Northeast Atlantic, meaning stocks around Europe have decreased by at least 95%. This is a direct result of overfishing to supply northern Europe's taste for rock salmon, saumonette, and zeepaling. Despite these alarming figures, very few management or conservation measures are in place for Squalus acanthias.[1] In EU waters, a Total Allowable Catch (TAC) has been in place since 1999, but until 2007 it only applied to ICES Areas IIa and IV. It was also set well above the actual weight of fish being caught until 2005, rendering it meaningless. Since 2009 a maximum landing size of one metre (3 ft 3 in) has been imposed in order to protect the most valuable mature females. The TAC for 2011 was set at 0 tons, ending targeted fishing for the species in EU waters. It remains to be seen if populations will be able to recover.[13]

In the recent past the European market for spiny dogfish has increased dramatically, which led to the overfishing and decline of the species. This drastic increase led to the creation and implementation of many fishery management policies placing restrictions on the fishing of spiny dogfish. However, since the species is a late-maturing fish, it takes a while to rebuild the population.

In 2010, Greenpeace International added the spiny dogfish to its seafood red list. "The Greenpeace International seafood red list is a list of fish that are commonly sold in supermarkets around the world, and which have a very high risk of being sourced from unsustainable fisheries."[14] In the same year, the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS; also known as the Bonn Convention) listed the species (Northern Hemisphere populations) under Annex I of its Migratory Shark Memorandum of Understanding.[15]

In recent years, however, the US has implemented fishing controls and opened up the fishery. The proposed quota for 2011 was 16.1 million kilograms (35.5 million lb) with a trip limit of 1,800 kg (4,000 lb), an increase over past years in which the quota has ranged from 2 to 9 million kilograms (5 to 20 million lb), with trip limits from 900 to 1,400 kg (2,000 to 3,000 lb).[16] In 2010, NOAA announced the Eastern US Atlantic spiny dogfish stocks to be rebuilt,[17] and in 2011, concerns about dogfish posing a serious predatory threat to other stocks resulted in an emergency amendment of the quota with nearly 6.8 million kilograms (15 million lb) being added.[18]

In June 2018, the New Zealand Department of Conservation classified Squalus acanthias Linnaeus as "Not Threatened" with the qualifier "Secure Overseas" under the New Zealand Threat Classification System.[19]

Fossil range

As a cartilaginous fish, shark tissues usually do not fossilize.

Squalus acanthias fossils date back to the Miocene 11 MYA.[20]

References

- Fordham, S.; Fowler, S.L.; Coelho, R.P.; Goldman, K.; Francis, M.P. (2016). "Squalus acanthias". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 20016: e.T91209505A2898271. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T91209505A2898271.en.

- "Squalus acanthias". Florida Museum. 2017-05-12. Retrieved 2018-12-03.

- "Species Squalus acanthias Linnaeus". FishWisePro. 1758. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- Ebert, D. A.; White, W. T.; Goldman, K. J.; Compagno, L. J.; Daly-Engel, T. S. & Ward, R. D. (2010). "Resurrection and redescription of Squalus suckleyi (Girard, 1854) from the North Pacific, with comments on the Squalus acanthias subgroup (Squaliformes: Squalidae)". Zootaxa. 2612: 22–40. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.2612.1.2.

- "Spiny Dogfish". Oceana. Retrieved 2019-02-22.

- "Squalus acanthias summary page". FishBase. Retrieved 2019-02-23.

- Kindersley, Dorling (2001). Animal. New York City: DK Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7894-7764-4.

- Jose I. Castro (2011). The Sharks of North America. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-19-539294-4.

- Bubley, W. J.; Kneebone, J.; Sulikowski, J. A.; Tsang, P. C. W. (2012). "Reassessment of spiny dogfish Squalus acanthias age and growth using vertebrae and dorsal-fin spines". Journal of Fish Biology. 80 (5): 1300–1319. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.2011.03171.x. ISSN 1095-8649. PMID 22497385.

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) (2011). Yearbook of fishery and aquaculture statistics 2009. Capture production (PDF). Rome: FAO. pp. 302–303.

- Katherine Sosebee; Paul Rago (December 2006). "Status of Fishery Resources off the Northeastern US: Spiny dogfish (Squalus acanthias)". NEFSC – Resource Evaluation and Assessment Division.

- Wilcox, Meg (2017-07-04). "Dogfish — it's what's for dinner on the Cape". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 2017-07-05.

- "Spurdog in the Northeast Atlantic" (PDF). Advice September 2011. ICES, Copenhagen. 2011. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- Greenpeace International Seafood Red list Archived February 5, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- Memorandum of Understanding on the Conservation of Migratory Sharks. PDF. Cms.int. Retrieved on 2016-11-14.

- "Mid-Atlantic Council Adopts Increase in Spiny Dogfish Quotas". Atlantic Highlands Herald. 19 October 2011. Archived from the original on 2 November 2013.

- NOAA Announces Recovery of Spiny Dogfish Stock. greateratlantic.fisheries.noaa.gov

- "Threat of Dogfish Sharks Unite Commercial and Recreational Fishermen From Maine to North Carolina". FishNet USA via Prnewswire. May 4, 2009.

- Duffy, Clinton A. J.; Francis, Malcolm; Dunn, M. R.; Finucci, Brit; Ford, Richard; Hitchmough, Rod; Rolfe, Jeremy (2018). Conservation status of New Zealand chondrichthyans (chimaeras, sharks and rays), 2016 (PDF). Wellington, New Zealand: Department of Conservation. p. 11. ISBN 9781988514628. OCLC 1042901090.

- http://fossilworks.org/bridge.pl?a=taxonInfo&taxon_no=151823. Missing or empty

|title=(help)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Squalus acanthias. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Squalus acanthias |

- Spiny dogfish at Animal Diversity Web

- "Squalus acanthias". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 24 January 2006.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2005). "Squalus acanthias" in FishBase. 10 2005 version.

- Canadian Shark Research Laboratory

- 3D model of a spiny dogfish splanchnocranium

- Photos of Spiny dogfish on Sealife Collection