Soluntum

Soluntum or Solus was an ancient city on the Tyrrhenian coast of Sicily near present-day Sòlanto in the commune of Santa Flavia, Italy. In antiquity, it was one of the three chief Phoenician settlements in the island.

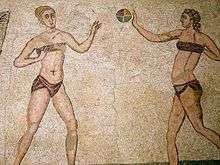

View of Solanto from the ruins of Soluntum | |

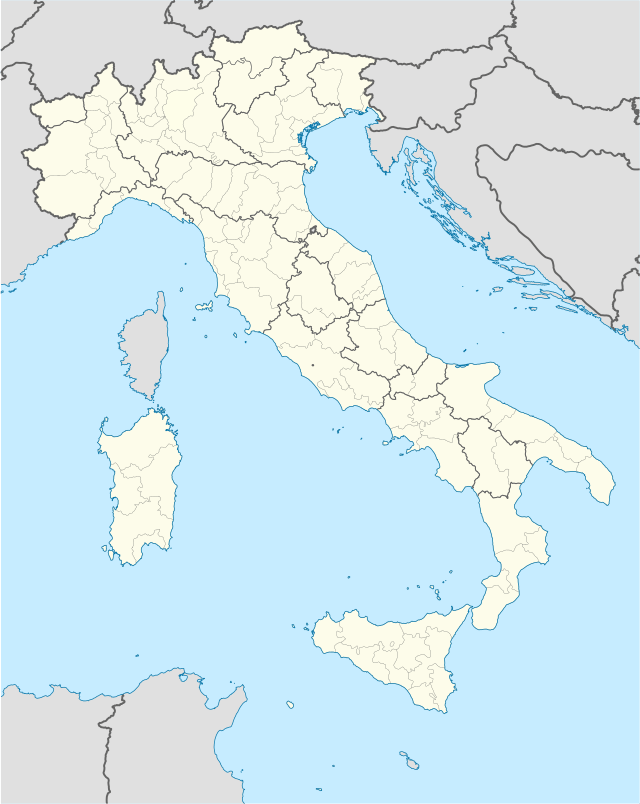

Shown within Italy | |

| Alternative name | Solus |

|---|---|

| Location | Solanto, Province of Palermo, Sicily, Italy |

| Coordinates | 38°04′27″N 13°32′29″E |

| Type | Settlement |

| Site notes | |

| Management | Soprintendenza BB.CC.AA. di Palermo |

| Public access | Yes |

| Website | Area Archeologica e Antiquarium di Solunto (in Italian) |

Names

The Punic name of the town was simply Kapara (𐤊𐤐𐤓𐤀, KPRʾ), meaning "Village".[1]

The Greek name appears in surviving coins as Solontînos (Σολοντῖνος) but appears variously in other sources as Solóeis (Σολόεις),[2] Soloûs (Σολοῦς),[3] and Solountînos.[4] Some scholars contend that Soluntum and Solus were two different cities at close quarters, Soluntum, higher upon the hillside, being a later habitation displacing the earlier settlement of Solus, at a lower elevation.[5] These were latinized as Soluntum and Solus, which became the modern Italian name Solunto.

Geography

Soluntum lay 183 m (600 ft) above sea level on the southeast side of Monte Catalfano (373 m or 1,225 ft), commanding a fine view from a naturally-strong situation.[6] It is immediately to the east of the bold promontory called Capo Zafferano. It is about 16 km (9.9 mi) east of Panormus (modern Palermo).

History

The date of its first occupation is—like that of Panormus (Palermo)—unknown. From its proximity to Panormus, Soluntum was one of the few colonies that the Phoenicians retained when they gave way before the advance of the Greek colonies in Sicily, and withdrew to the northwest corner of the island.[7] It then passed together with Panormus and Motya into the hands of the Carthaginians, or at least became a dependency of that people. It continued steadfast to the Carthaginian alliance even in 397 BCE, when the formidable armament of Dionysius shook the fidelity of most of their allies;[8] its territory was in consequence ravaged by Dionysius, but without effect. At a later period of the war (396 BCE) it was betrayed into the hands of that despot,[9] but probably soon fell again into the power of the Carthaginians. It was certainly one of the cities that usually formed part of their dominions in the island; and in 307 BCE it was given up by them to the soldiers and mercenaries of Agathocles, who had made peace with the Carthaginians when abandoned by their leader in Africa.[10] During the First Punic War we find it still subject to Carthage, and it was not till after the fall of Panormus that Soluntum also opened its gates to the Romans.[11] It continued to subsist under the Roman dominion as a municipal town, but apparently one of no great importance, as its name is only slightly and occasionally mentioned by Cicero.[12] But it is still noticed both by Pliny and Ptolemy,[13] where the name is corruptly written Ὀλουλίς), as well as at a later period by the Itineraries, which place it 12 miles from Panormus and 12 from Thermae (modern Termini Imerese).[14] Soluntum minted coins in antiquity. It is probable that its complete destruction dates from the time of the Saracens.[15]

Excavations and remains

Excavations have brought to light considerable remains of the ancient town, belonging entirely to the Roman period, and a good deal still remains unexplored.[6] The traces of two ancient roads, paved with large blocks of stone, which led up to the city, may still be followed, and the whole summit of Monte Catalfano is covered with fragments of ancient walls and foundations of buildings. Among these may be traced the remains of two temples, of which some capitals and portions of friezes, have been discovered. An archaic oriental Artemis sitting between a lion and a panther, found here, is in the museum at Palermo, with other antiquities from this site. An inscription, erected by the citizens in honor of Fulvia Plautilla, the wife of Caracalla, was found there in 1857.[16] With the exception of the winding road by which the town was approached on the south, the streets, despite the unevenness of the ground, which in places is so steep that steps have to be introduced, are laid out regularly, running from east to west and from north to south, and intersecting at right angles. They are as a rule paved with slabs of stone. The houses were constructed of rough walling, which was afterwards plastered over; the natural rock is often used for the lower part of the walls. One of the largest of them, with a peristyle, was in 1911, though wrongly, called the gymnasium. Near the top of the town are some cisterns cut in the rock, and at the summit is a larger house than usual, with mosaic pavements and paintings on its walls. Several sepulchres also have been found.[6]

See also

References

Citations

- Head & al. (1911), p. 877.

- Thuc.

- Diod., Eth.

- Diod.

- Richard Talbert, Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World, (ISBN 0-691-03169-X), Map 47, notes.

- Ashby 1911, p. 368.

- Bunbury 1857, p. 1021 cites: Thuc. vi. 2.

- Bunbury 1857, p. 1021 cites: Diod. xiv. 48.

- Bunbury 1857, p. 1021 cites: Diod. xiv. 78.

- Bunbury 1857, p. 1021 cites: Diod. xx. 69.

- Bunbury 1857, p. 1021 cites: Diod. xxiii. p. 505.

- Bunbury 1857, p. 1021 cites: In Verrem ii. 42, iii. 43.)

- Bunbury 1857, p. 1021 cites: Pliny iii. 8. s. 14; Ptol. iii. 4. § 3.

- Bunbury 1857, p. 1021 cites: Antonine Itinerary p. 91; Tabula Peutingeriana.

- Bunbury 1857, p. 1021.

- Bunbury 1857, p. 1021 cites: Tommaso Fazello de Reb. Sic. viii. p. 352; Amico, Lex. Top. vol. ii. pp. 192-95; Hoare's Class. Tour, vol. ii. p. 234; Serra di Falco, Ant. della Sicilia, vol. v. pp. 60-67.

Bibliography

- Head, Barclay; et al. (1911), "Zeugitana", Historia Numorum (2nd ed.), Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp. 877–882.