In Verrem

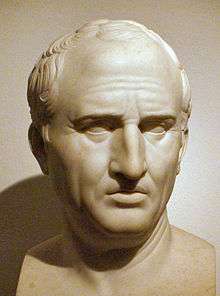

In Verrem ("Against Verres") is a series of speeches made by Cicero in 70 BC, during the corruption and extortion trial of Gaius Verres, the former governor of Sicily. The speeches, which were concurrent with Cicero's election to the aedileship, paved the way for Cicero's public career.

Background to the case

During the Civil War between Marius and Sulla (88–87 BC), Verres had been a junior officer in a Marian legion under Gaius Papirius Carbo. He saw the tides of the war shifting to Sulla, and so, Cicero alleged, went over to Sulla's lines bearing his legion's paychest.[1]

Afterwards, he was protected to a degree by Sulla, and allowed to indulge a skill for gubernatorial extortion in Cilicia under the province's governor, Gnaeus Cornelius Dolabella in 81 BC.[2] By 73 BC he had been placed as governor of Sicily, one of the key grain-producing provinces of the Republic (Egypt at this time was still an independent Hellenistic kingdom). In Sicily, Verres was alleged to have despoiled temples and used a number of national emergencies, including the Third Servile War, as cover for elaborate extortion plots.[3]

At the same time, Marcus Tullius Cicero was an up-and-coming political figure. After defending Sextus Roscius of Ameria in 80 BC on a highly politically charged case of parricide, Cicero left for a voyage to Greece and Rhodes. There, he learned a new and less-strenuous form of oratory from Molon of Rhodes before rushing back into the political arena upon Sulla's death. Cicero would serve in Sicily in 75 BC as a quaestor, and in doing so made contacts with a number of Sicilian towns. In fact a large amount of his clientele at the time came from Sicily, a link that would prove invaluable in 70 BC, when a deputation of Sicilians asked Cicero to level a prosecution against Verres for his alleged crimes on the island.

First speech

The first speech was the only one to be delivered in front of the praetor urbanus Manius Acilius Glabrio. In it, Cicero took advantage of the almost unconditional freedom to speak in court to demolish Verres' case.

Cicero touched very little on Verres' extortion crimes in Sicily in the first speech. Instead, he took a two-pronged approach, by both inflating the vanity of the all-senator jury and making the most of Verres' early character. The second approach concerned Verres' defense's attempts to keep the case from proceeding on technicalities.

Verres had secured the services of the finest orator of his day, Quintus Hortensius Hortalus for his defense. Immediately, both Verres and Hortensius realized that the court as composed under Glabrio was inhospitable to the defense, and began to try to derail the prosecution by procedural tricks that had the effect of delaying or prolonging the trial. This was done by first trying to place a similar prosecution on the docket, to take place before Verres' trial, one concerning a governor of Bithynia for extortion.

The point of the attempted derailment of the case hinged on Roman custom. At the time the case was being argued, the year was coming to a close and soon a number of public festivals (including one in honor of Pompey the Great) would commence. All work ceased on festival days, according to Roman customs, including any ongoing trials. Cicero alleged that Hortensius was hoping to draw the trial out long enough to run into the festival period before Cicero would have an opportunity to conclude his case, thereby making it a statistical impossibility that Glabrio and the jury would deliver a verdict before the new year, when the magistrates were replaced with their newly elected successors.

Hortensius and Verres both knew, Cicero argued, that Marcus Metellus, a friend and ally of Verres, would be in charge of the extortion court in the new year, and so saw a benefit to such a gaming of the system. In addition, Hortensius himself, along with Quintus Metellus, Marcus's older brother, had been elected consuls for the same year, and would thus be in prime position to intimidate the witnesses when the case resumed after the expected lull. As such, Verres and his supporters were supremely confident of victory. Indeed, Cicero remarked that, immediately after the election of Hortensius and Metellus, one of his friends had heard the former consul Gaius Scribonius Curio publicly congratulate Verres, declaring that he was now as good as acquitted.

Cicero, too, had a unique strategy in mind for his prosecution. In 81 BC, the Dictator Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix had changed the composition of criminal courts, allowing only Senators to serve as jurymen. This had, apparently, caused friction and at least the appearance of "bought" justice, particularly when Senators were the accused, or the interests of a popular or powerful Senator were threatened. There had also been, concurrent with this, an almost perpetual scandal of wealthy senators and knights bribing juries to gain verdicts favorable to them. By 70, as the trial against Verres was proceeding, Lucius Aurelius Cotta had introduced a law that would reverse Sulla's restrictions on jury composition, once again opening the juries up to Senators, Equites and tribuni aerarii as a check on such over-lenient juries. Cicero devoted a significant amount of time in his oration to the perception of Senatorial juries, arguing that not only was Verres on trial for his malfeasance in Sicily, but the Senate was on trial as well for charges of impropriety, and that whatever verdict they handed down to Verres would reflect on them to either their credit or shame. The surest way, Cicero argued, to get the Lex Aurelia passed and take the juries away from the Senate was to acquit Verres on all charges.

Further, to counteract Hortensius' attempts to draw the trial out, Cicero begged the court's indulgence to allow him to alter the trial's flow from the usual format. In normal trials, both prosecution and defense would make a series of adversarial speeches before witnesses were called. Cicero realized that this would inevitably drag out the proceedings past the new year, and so he requested that he be allowed to call witnesses immediately to buttress his charges, before the speeches were made.[4]

Outline of the main charges in second speech

The first speech had touched more on the sharp practice of Verres and his attorney, Hortensius, in trying to derail or delay the trial. In the second, infinitely more damning speech, Cicero laid out the full charge sheet. The second speech apparently was meant to have been his rebuttal speech had the trial continued, as it alludes to witnesses as already having testified in front of Glabrio's court.

Cicero enumerated a number of charges against Verres during his tenure as governor of Sicily. The main ones that serve as the greatest portion of the text concern a naval scandal that Verres had fomented as a complex means of embezzlement. These were that he subverted Roman security by accepting a bribe from the city of Messana to release them from their duty of providing a ship for the Roman fleet and that he fraudulently discharged men from fleet service, did not mark them down as discharged, and pocketed their active duty pay. Pirates that were captured were sometimes sold under the table by Verres as slaves, rather than being executed, as Cicero argues was the proper punishment. To camouflage the fact that this was going on, Cicero further accuses Verres of administratively shuffling around the pirates to cities that had no knowledge of them and substituting others in their place on the execution block.

Moreover, Cicero alleges that Verres placed a crony of his, Cleomenes by name, as commander of a fleet expedition to destroy a group of pirates in the area (the reason being, Cicero argues, to keep him out of reach as Verres cuckolded him) and that Cleomenes, due to incompetence, allowed the pirates to enter into Syracuse harbor and sack the town. Further, after the abject failure of Cleomenes' expedition, to keep the blame off himself for allowing the fleet to go out undermanned and ill-led, Verres ordered all the ships' captains except for Cleomenes to be executed. More charges were levelled outside of this naval affair. They include:

- A scheme of extortion centered on the Third Servile War, in which Verres allegedly would accuse key slaves of wealthy landowners of being in league with the rebelling slaves on the mainland, arresting them and then soliciting large bribes to void the charges;

- He ordered ships that had valuable cargoes impounded as allegedly belonging to the rebel Quintus Sertorius. Passengers and crew on board the ships were then thrown in a prison created out of an old rock quarry by the tyrant Dionysius I in Syracuse, and were executed without trial as alleged sympathizers or soldiers of Sertorius.

- one prisoner of Verres' scheme, Publius Gavius, a Roman citizen of Compsa, escaped and protested about Verres' treatment of Roman citizens. Verres had the man flogged, and then he had him crucified, both punishments not to be inflicted on a Roman citizen without a trial in Rome (and even then, an execution by crucifixion was never to be performed on a Roman citizen). To add to the humiliation, Verres was alleged to have placed the cross bearing Gavius on a spot where the coastline of mainland Italy (symbolically the border of Verres' power) could be seen by him as he died.

- He ordered his lictors and his chief lictor, Sextus in particular, to beat an elderly man of Panormus, a Roman citizen named Gaius Servilius, to near-death for criticizing Verres' rule. Servilius later died of his injuries.

Outcome of the speeches

Of the planned orators, only Cicero had an opportunity to speak. Cicero detailed Verres' early crimes and Verres' attempts to derail the trial. Soon after the court heard Cicero's speeches, Hortensius advised Verres that it would be hard for him to win at this point, and further advised that the best course of action was for Verres to essentially plead no contest by going into voluntary exile (an option open to higher-ranking Romans in his situation). By the end of 70 BC, Verres was living in exile in Massilia, modern-day Marseilles, where he would live the rest of his life (history records he was killed during the proscriptions of the Second Triumvirate over a sculpture desired by Mark Antony). Cicero collected the remaining material, including what was to be his second speech dealing with Verres' actions in Sicily, and published it as if it had actually been delivered in court. Further, due to the legal system in Rome, Senators who won prosecutions were entitled to the accused's position in the Senate. This gave Cicero's career a boost, in a large part because this allowed him a freedom to speak not usually granted to a newly enrolled member of the Senate.

References

- In Verrem I.11

- Badian, Ernst BadianErnst (2012-12-20), "Cornelius (RE 135) Dolabella (2), Gnaeus", The Oxford Classical Dictionary, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780199545568.001.0001/acref-9780199545568-e-1843, ISBN 9780199545568, retrieved 2019-06-15

- In Verrem I.14–16, II.5–12

- In Verrem I.54–55

Further reading

- Excerpts from an English translation of the speeches are published in "Introduction: 5 Books of the Second Action Against Verres", in C. D. Yonge, ed., The Orations of M. Tullius Cicero (London: George Bell & Sons, 1903), available online: uah.edu

- Imperium by Robert Harris. A novel which focuses on the life of Cicero as told by his slave and friend Tiro.

Interesting reading: Patricia Rosenmeyer. “From Syracuse to Rome: The Travails of Silanion's Sappho.” Transactions of the American Philological Association, vol. 137, no. 2, 2007, pp. 277–303. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4543316.

External links