Socialization

In sociology, socialization is the process of internalizing the norms and ideologies of society. Socialization encompasses both learning and teaching and is thus "the means by which social and cultural continuity are attained".[1]:5[2]

Socialization is strongly connected to developmental psychology.[3] Humans need social experiences to learn their culture and to survive.[4]

Socialization essentially represents the whole process of learning throughout the life course and is a central influence on the behavior, beliefs, and actions of adults as well as of children.[5][6]

Socialization may lead to desirable outcomes—sometimes labeled "moral"—as regards the society where it occurs. Individual views are influenced by the society's consensus and usually tend toward what that society finds acceptable or "normal". Socialization provides only a partial explanation for human beliefs and behaviors, maintaining that agents are not blank slates predetermined by their environment;[7] scientific research provides evidence that people are shaped by both social influences and genes.[8][9][10][11]

Genetic studies have shown that a person's environment interacts with their genotype to influence behavioral outcomes.[12]

History

Notions of society and the state of nature have existed for centuries.[1]:20 In its earliest usages, socialization was simply the act of socializing or another word for socialism.[13][14][15][16] Socialization as a concept originated concurrently with sociology, as sociology was defined as the treatment of "the specifically social, the process and forms of socialization, as such, in contrast to the interests and contents which find expression in socialization".[17] In particular, socialization consisted of the formation and development of social groups, and also the development of a social state of mind in the individuals who associate. Socialization is thus both a cause and an effect of association.[18] The term was relatively uncommon before 1940, but became popular after World War II, appearing in dictionaries and scholarly works such as the theory of Talcott Parsons.[19]

Stages of moral development

Lawrence Kohlberg studied moral reasoning and developed a theory of how individuals reason situations as right from wrong. The first stage is the pre-conventional stage, where a person (typically children) experience the world in terms of pain and pleasure, with their moral decisions solely reflecting this experience. Second, the conventional stage (typical for adolescents and adults) is characterized by an acceptance of society's conventions concerning right and wrong, even when there are no consequences for obedience or disobedience. Finally, the post-conventional stage (more rarely achieved) occurs if a person moves beyond society's norms to consider abstract ethical principles when making moral decisions.[20]

Stages of psychosocial development

Erik H. Erikson (1902–1994) explained the challenges throughout the life course. The first stage in the life course is infancy, where babies learn trust and mistrust. The second stage is toddlerhood where children around the age of two struggle with the challenge of autonomy versus doubt. In stage three, preschool, children struggle to understand the difference between initiative and guilt. Stage four, pre-adolescence, children learn about industriousness and inferiority. In the fifth stage called adolescence, teenagers experience the challenge of gaining identity versus confusion. The sixth stage, young adulthood, is when young people gain insight to life when dealing with the challenge of intimacy and isolation. In stage seven, or middle adulthood, people experience the challenge of trying to make a difference (versus self-absorption). In the final stage, stage eight or old age, people are still learning about the challenge of integrity and despair.[21] This concept has been further developed by Klaus Hurrelmann and Gudrun Quenzel using the dynamic model of "developmental tasks".[22]

Behaviorism

George Herbert Mead (1863–1931) developed a theory of social behaviorism to explain how social experience develops an individual's self-concept. Mead's central concept is the self: It is composed of self-awareness and self-image. Mead claimed that the self is not there at birth, rather, it is developed with social experience. Since social experience is the exchange of symbols, people tend to find meaning in every action. Seeking meaning leads us to imagine the intention of others. Understanding intention requires imagining the situation from the others' point of view. In effect, others are a mirror in which we can see ourselves. Charles Horton Cooley (1902-1983) coined the term looking glass self, which means self-image based on how we think others see us. According to Mead, the key to developing the self is learning to take the role of the other. With limited social experience, infants can only develop a sense of identity through imitation. Gradually children learn to take the roles of several others. The final stage is the generalized other, which refers to widespread cultural norms and values we use as a reference for evaluating others.[23]

Contradictory evidence to behaviorism

Behaviorism makes claims that when infants are born they lack social experience or self. The social pre-wiring hypothesis, on the other hand, shows proof through a scientific study that social behavior is partly inherited and can influence infants and also even influence foetuses. Wired to be social means that infants are not taught that they are social beings, but they are born as prepared social beings.

The social pre-wiring hypothesis refers to the ontogeny of social interaction. Also informally referred to as, "wired to be social". The theory questions whether there is a propensity to socially oriented action already present before birth. Research in the theory concludes that newborns are born into the world with a unique genetic wiring to be social.[24]

Circumstantial evidence supporting the social pre-wiring hypothesis can be revealed when examining newborns' behavior. Newborns, not even hours after birth, have been found to display a preparedness for social interaction. This preparedness is expressed in ways such as their imitation of facial gestures. This observed behavior cannot be contributed to any current form of socialization or social construction. Rather, newborns most likely inherit to some extent social behavior and identity through genetics.[24]

Principal evidence of this theory is uncovered by examining Twin pregnancies. The main argument is, if there are social behaviors that are inherited and developed before birth, then one should expect twin foetuses to engage in some form of social interaction before they are born. Thus, ten foetuses were analyzed over a period of time using ultrasound techniques. Using kinematic analysis, the results of the experiment were that the twin foetuses would interact with each other for longer periods and more often as the pregnancies went on. Researchers were able to conclude that the performance of movements between the co-twins were not accidental but specifically aimed.[24]

The social pre-wiring hypothesis was proved correct, "The central advance of this study is the demonstration that 'social actions' are already performed in the second trimester of gestation. Starting from the 14th week of gestation twin foetuses plan and execute movements specifically aimed at the co-twin. These findings force us to predate the emergence of social behavior: when the context enables it, as in the case of twin foetuses, other-directed actions are not only possible but predominant over self-directed actions."[24]

Primary socialization

Primary socialization for a child is very important because it sets the groundwork for all future socialization. Primary Socialization occurs when a child learns the attitudes, values, and actions appropriate to individuals as members of a particular culture. It is mainly influenced by the immediate family and friends. For example, if a child saw his/her mother expressing a discriminatory opinion about a minority, or majority group, then that child may think this behavior is acceptable and could continue to have this opinion about minority/majority groups.

Secondary socialization

Secondary socialization refers to the process of learning what is the appropriate behavior as a member of a smaller group within the larger society. Basically, is the behavioral patterns reinforced by socializing agents of society. Secondary socialization takes place outside the home. It is where children and adults learn how to act in a way that is appropriate for the situations they are in.[25] Schools require very different behavior from the home, and children must act according to new rules. New teachers have to act in a way that is different from pupils and learn the new rules from people around them.[25] Secondary socialization is usually associated with teenagers and adults, and involves smaller changes than those occurring in primary socialization. Such examples of secondary socialization are entering a new profession or relocating to a new environment or society.

Anticipatory socialization

Anticipatory socialization refers to the processes of socialization in which a person "rehearses" for future positions, occupations, and social relationships. For example, a couple might move in together before getting married in order to try out, or anticipate, what living together will be like.[26] Research by Kenneth J. Levine and Cynthia A. Hoffner suggests that parents are the main source of anticipatory socialization in regards to jobs and careers.[27]

Resocialization

Resocialization refers to the process of discarding former behavior patterns and reflexes, accepting new ones as part of a transition in one's life. This occurs throughout the human life cycle.[28] Resocialization can be an intense experience, with the individual experiencing a sharp break with his or her past, as well as a need to learn and be exposed to radically different norms and values. One common example involves resocialization through a total institution, or "a setting in which people are isolated from the rest of society and manipulated by an administrative staff". Resocialization via total institutions involves a two step process: 1) the staff work to root out a new inmate's individual identity & 2) the staff attempt to create for the inmate a new identity.[29] Other examples of this are the experience of a young man or woman leaving home to join the military, or a religious convert internalizing the beliefs and rituals of a new faith. An extreme example would be the process by which a transsexual learns to function socially in a dramatically altered gender role.

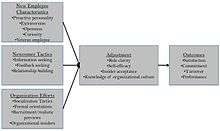

Organizational socialization

Organizational socialization is the process whereby an employee learns the knowledge and skills necessary to assume his or her organizational role.[30] As newcomers become socialized, they learn about the organization and its history, values, jargon, culture, and procedures. This acquired knowledge about new employees' future work environment affects the way they are able to apply their skills and abilities to their jobs. How actively engaged the employees are in pursuing knowledge affects their socialization process.[31] They also learn about their work group, the specific people they work with on a daily basis, their own role in the organization, the skills needed to do their job, and both formal procedures and informal norms. Socialization functions as a control system in that newcomers learn to internalize and obey organizational values and practices.

Group socialization

Group socialization is the theory that an individual's peer groups, rather than parental figures, are the primary influence of personality and behavior in adulthood.[32] Parental behavior and the home environment has either no effect on the social development of children, or the effect varies significantly between children.[33] Adolescents spend more time with peers than with parents. Therefore, peer groups have stronger correlations with personality development than parental figures do.[34] For example, twin brothers, whose genetic makeup are identical, will differ in personality because they have different groups of friends, not necessarily because their parents raised them differently. Behavioral genetics suggest that up to fifty percent of the variance in adult personality is due to genetic differences.[35] The environment in which a child is raised accounts for only approximately ten percent in the variance of an adult's personality.[36] As much as twenty percent of the variance is due to measurement error.[37] This suggests that only a very small part of an adult's personality is influenced by factors parents control (i.e. the home environment). Harris claims that while it's true that siblings don't have identical experiences in the home environment (making it difficult to associate a definite figure to the variance of personality due to home environments), the variance found by current methods is so low that researchers should look elsewhere to try to account for the remaining variance.[32] Harris also states that developing long-term personality characteristics away from the home environment would be evolutionarily beneficial because future success is more likely to depend on interactions with peers than interactions with parents and siblings. Also, because of already existing genetic similarities with parents, developing personalities outside of childhood home environments would further diversify individuals, increasing their evolutionary success.[32]

Entering high school is a crucial moment in many adolescent's lifespan involving the branching off from the restraints of their parents. When dealing with new life challenges, adolescents take comfort in discussing these issues within their peer groups instead of their parents.[38] Peter Grier, staff writer of the Christian Science Monitor describes this occurrence as,"Call it the benign side of peer pressure. Today's high-schoolers operate in groups that play the role of nag and nanny-in ways that are both beneficial and isolating."[39]

Stages

Individuals and groups change their evaluations and commitments to each other over time. There is a predictable sequence of stages that occur in order for an individual to transition through a group; investigation, socialization, maintenance, resocialization, and remembrance. During each stage, the individual and the group evaluate each other which leads to an increase or decrease in commitment to socialization. This socialization pushes the individual from prospective, new, full, marginal, and ex member.[40]

Stage 1: Investigation This stage is marked by a cautious search for information. The individual compares groups in order to determine which one will fulfill their needs (reconnaissance), while the group estimates the value of the potential member (recruitment). The end of this stage is marked by entry to the group, whereby the group asks the individual to join and they accept the offer.

Stage 2: Socialization Now that the individual has moved from prospective member to new member, they must accept the group's culture. At this stage, the individual accepts the group's norms, values, and perspectives (assimilation), and the group adapts to fit the new member's needs (accommodation). The acceptance transition point is then reached and the individual becomes a full member. However, this transition can be delayed if the individual or the group reacts negatively. For example, the individual may react cautiously or misinterpret other members' reactions if they believe that they will be treated differently as a newcomer.

Stage 3: Maintenance During this stage, the individual and the group negotiate what contribution is expected of members (role negotiation). While many members remain in this stage until the end of their membership, some individuals are not satisfied with their role in the group or fail to meet the group's expectations (divergence).

Stage 4: Resocialization If the divergence point is reached, the former full member takes on the role of a marginal member and must be resocialized. There are two possible outcomes of resocialization: differences are resolved and the individual becomes a full member again (convergence), or the group expels the individual or the individual decides to leave (exit).

Stage 5: Remembrance In this stage, former members reminisce about their memories of the group, and make sense of their recent departure. If the group reaches a consensus on their reasons for departure, conclusions about the overall experience of the group become part of the group's tradition.

Gender socialization

Henslin (1999:76) contends that "an important part of socialization is the learning of culturally defined gender roles." Gender socialization refers to the learning of behavior and attitudes considered appropriate for a given sex. Boys learn to be boys and girls learn to be girls. This "learning" happens by way of many different agents of socialization. The behaviour that is seen to be appropriate for each gender is largely determined by societal, cultural and economic values in a given society. Gender socialization can therefore vary considerably among societies with different values. The family is certainly important in reinforcing gender roles, but so are groups including friends, peers, school, work and the mass media. Gender roles are reinforced through "countless subtle and not so subtle ways" (1999:76). In peer group activities, stereotypic gender roles may also be rejected, renegotiated or artfully exploited for a variety of purposes.[41]

Carol Gilligan compared the moral development of girls and boys in her theory of gender and moral development. She claimed (1982, 1990) that boys have a justice perspective meaning that they rely on formal rules to define right and wrong. Girls, on the other hand, have a care and responsibility perspective where personal relationships are considered when judging a situation. Gilligan also studied the effect of gender on self-esteem. She claimed that society's socialization of females is the reason why girls' self-esteem diminishes as they grow older. Girls struggle to regain their personal strength when moving through adolescence as they have fewer female teachers and most authority figures are men.[42]

As parents are present in a child's life from the beginning, their influence in a child's early socialization is very important, especially in regards to gender roles. Sociologists have identified four ways in which parents socialize gender roles in their children: Shaping gender related attributes through toys and activities, differing their interaction with children based on the sex of the child, serving as primary gender models, and communicating gender ideals and expectations.[43]

Sociologist of gender R.W. Connell contends that socialization theory is "inadequate" for explaining gender, because it presumes a largely consensual process except for a few "deviants," when really most children revolt against pressures to be conventionally gendered; because it cannot explain contradictory "scripts" that come from different socialization agents in the same society, and because it does not account for conflict between the different levels of an individual's gender (and general) identity.[44]

Racial socialization

Racial socialization, or racial-ethnic socialization (Q96195578), has been defined as "the developmental processes by which children acquire the behaviors, perceptions, values, and attitudes of an ethnic group, and come to see themselves and others as members of the group".[45] The existing literature conceptualizes racial socialization as having multiple dimensions. Researchers have identified five dimensions that commonly appear in the racial socialization literature: cultural socialization, preparation for bias, promotion of mistrust, egalitarianism, and other.[46] Cultural socialization refers to parenting practices that teach children about their racial history or heritage and is sometimes referred to as pride development. Preparation for bias refers to parenting practices focused on preparing children to be aware of, and cope with, discrimination. Promotion of mistrust refers to the parenting practices of socializing children to be wary of people from other races. Egalitarianism refers to socializing children with the belief that all people are equal and should be treated with a common humanity.[46]

Oppression socialization

Oppression socialization refers to the process by which "individuals develop understandings of power and political structure, particularly as these inform perceptions of identity, power, and opportunity relative to gender, racialized group membership, and sexuality."[47] This action is a form of political socialization in its relation to power and the persistent compliance of the disadvantaged with their oppression using limited "overt coercion."[47]

Language socialization

Based on comparative research in different societies, focusing on the role of language in child development, linguistic anthropologists Elinor Ochs and Bambi Schieffelin have developed the theory of language socialization.[48] They discovered that the processes of enculturation and socialization do not occur apart from the process of language acquisition, but that children acquire language and culture together in what amounts to an integrated process. Members of all societies socialize children both to and through the use of language; acquiring competence in a language, the novice is by the same token socialized into the categories and norms of the culture, while the culture, in turn, provides the norms of the use of language.

Planned socialization

Planned socialization occurs when other people take actions designed to teach or train others. This type of socialization can take on many forms and can occur at any point from infancy onward.[49]

Natural socialization

Natural socialization occurs when infants and youngsters explore, play and discover the social world around them. Natural socialization is easily seen when looking at the young of almost any mammalian species (and some birds). Planned socialization is mostly a human phenomenon; all through history, people have been making plans for teaching or training others. Both natural and planned socialization can have good and bad qualities: it is useful to learn the best features of both natural and planned socialization in order to incorporate them into life in a meaningful way.[49]

Positive socialization

Positive socialization is the type of social learning that is based on pleasurable and exciting experiences. We tend to like the people who fill our social learning processes with positive motivation, loving care, and rewarding opportunities. Positive socialization occurs when desirable behaviours are reinforced with a reward, encouraging the individual to continue exhibiting similar behaviours in the future.[49]

Negative socialization

Negative socialization occurs when others use punishment, harsh criticisms or anger to try to "teach us a lesson;" and often we come to dislike both negative socialization and the people who impose it on us.[49] There are all types of mixes of positive and negative socialization, and the more positive social learning experiences we have, the happier we tend to be—especially if we are able to learn useful information that helps us cope well with the challenges of life. A high ratio of negative to positive socialization can make a person unhappy, leading to defeated or pessimistic feelings about life.[49]

Institutions

In the social sciences, institutions are the structures and mechanisms of social order and cooperation governing the behavior of individuals within a given human collectivity. Institutions are identified with a social purpose and permanence, transcending individual human lives and intentions, and with the making and enforcing of rules governing cooperative human behavior.[50]

Productive processing of reality

From the late 1980s, sociological and psychological theories have been connected with the term socialization. One example of this connection is the theory of Klaus Hurrelmann. In his book Social Structure and Personality Development,[51] he develops the model of productive processing of reality. The core idea is that socialization refers to an individual's personality development. It is the result of the productive processing of interior and exterior realities. Bodily and mental qualities and traits constitute a person's inner reality; the circumstances of the social and physical environment embody the external reality. Reality processing is productive because human beings actively grapple with their lives and attempt to cope with the attendant developmental tasks. The success of such a process depends on the personal and social resources available. Incorporated within all developmental tasks is the necessity to reconcile personal individuation and social integration and so secure the "I-dentity".[51]:42 The process of productive processing of reality is an enduring process throughout the life course.[52]

Oversocialization

The problem of order or Hobbesian problem questions the existence of social orders and asks if it is possible to oppose them. Émile Durkheim viewed society as an external force controlling individuals through the imposition of sanctions and codes of law. However, constraints and sanctions also arise internally as feelings of guilt or anxiety. If conformity as an expression of the need for belonging, the process of socialization is not necessarily universal. Behavior may not be influenced by society at all, but instead, be determined biologically.[53] The behavioral sciences during the second half of the twentieth century were dominated by two contrasting models of human political behavior, homo economicus and cultural hegemony, collectively termed the standard social science model. The fields of sociobiology and evolutionary psychology developed in response notions such as dominance hierarchies, cultural group selection, and dual inheritance theory. Behavior is the result of a complex interaction between nature and nurture, or genes and culture.[54] A focus on innate behavior at the expense of learning is termed undersocialization, while attributing behavior to learning when it is the result of evolution is termed oversocialization.[55]

See also

References

- Clausen, John A. (ed.) (1968) Socialisation and Society, Boston: Little Brown and Company

- Macionis, John J. (2013). Sociology (15th ed.). Boston: Pearson. p. 126. ISBN 978-0133753271.

- Billingham, M. (2007) Sociological Perspectives p.336 In Stretch, B. and Whitehouse, M. (eds.) (2007) Health and Social Care Book 1. Oxford: Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-435-49915-0

- Macionis, John J., and Linda M. Gerber. Sociology. Toronto: Pearson Canada, 2011. Print.

- MLA Style: "socialization." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica Student and Home Edition. Chicago: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2010.

- Cromdal, Jakob (2006). "Socialization". In K. Brown (ed.). Encyclopedia of language and linguistics. North-Holland: Elsevier. pp. 462–66. doi:10.1016/B0-08-044854-2/00353-9. ISBN 978-0080448541.

- Pinker, Steven. The Blank Slate. New York: Penguin Books, 2002.

- Dusheck, Jennie, "The Interpretation of Genes". Natural History, October 2002.

- Carlson, N.R.; et al. (2005) Psychology: the science of behavior. Pearson (3rd Canadian edition). ISBN 0-205-45769-X.

- Ridley, M. (2003) Nature Via Nurture: Genes, Experience, and What Makes us Human. Harper Collins. ISBN 0-00-200663-4.

- Westen, D. (2002) Psychology: Brain, Behavior & Culture. Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-38754-1.

- Kendler, K.S. and Baker, J.H. (2007). "Genetic influences on measures of the environment: a systematic review". Psychological Medicine. 37 (5): 615–26. doi:10.1017/S0033291706009524. PMID 17176502.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Fourier and his partisans". The London Phalanx. 6 September 1841. p. 505. hdl:2027/pst.000055430180.

- The Gentleman's Magazine. F. Jefferies. 1851. p. 465. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- "socialization, n." OED Online. Oxford University Press. March 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- St. Martin, Jenna (May 2007). "Socialization": The Politics and History of a Psychological Concept, 1900-1970 (Master's Thesis). Wesleyan University. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- Simmel, Georg (1 January 1895). "The Problem of Sociology". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 6 (3): 52–63. doi:10.1177/000271629500600304. JSTOR 1009553.

- Giddings, Franklin Henry (1897). The theory of socialization. A syllabus of sociological principles. New York: The Macmillan company. pp. 1–2. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- Morawski, Jill G.; St. Martin, Jenna (2011). "The evolving vocabulary of the social sciences: The case of "socialization"". History of Psychology. 14 (1): 2. doi:10.1037/a0021984. PMID 21688750.

- Macionis, Gerber 2010 108

- Macionis, Gerber, John, Linda (2010). Sociology 7th Canadian Ed. Toronto, Ontario: Pearson Canada Inc. p. 111.

- Hurrelmann, Klaus and Quenzel, Gudrun (2019) Developmental Tasks in Adolescence. London/New York: Routledge

- Macionis, Gerber, John, Linda (2010). Sociology 7th Canadian Ed. Toronto, Ontario: Pearson Canada Inc. p. 109.

- Umberto Castiello; et al. (7 October 2010). "Wired to Be Social: The Ontogeny of Human Interaction". PLoS ONE. 5 (10): e13199. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...513199C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013199. PMC 2951360. PMID 20949058.

- "Bassaleg" (PDF).

- "SparkNotes: Socialization".

- Levine, K.J.; Hoffner, C.A. (2006). "Adolescents' conceptions of work: What is learned from different sources during anticipatory socialization?". Journal of Adolescent Research. 21 (6): 647–69. doi:10.1177/0743558406293963.

- (Schaefer & Lamm, 1992: 113)

- Macionis, John J. "Sociology: 7th Canadian Edition". (Toronto: Pearson, 2011), 120-121

- Adam, Alvenfors (1 January 2010). "Introduktion – Integration? : Om introduktionsprogrammets betydelse för integration av nyanställda". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Kammeyer-Mueller, J.D.; Wanberg, C.R. (2003). "Unwrapping the organizational entry process: Disentangling antecedents and their pathways to adjustment". Journal of Applied Psychology. 88 (5): 779–94. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.318.5702. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.779. PMID 14516244.

- Harris, J.R. (1995). "Where is the child's environment? A group socialization theory of development". Psychological Review. 102 (3): 458–89. doi:10.1037/0033-295x.102.3.458.

- Maccoby, E.E. & Martin, J.A. (1983). Socialization in the context of the family: Parent-child interaction. In P.H. Mussen (Series Ed.) & E.M. Hetherington (Vol. Ed.), Handbook of Child Psychology: Vol. 4. Socialization, personality, and social development (4th ed., pp. 1–101). New York: Wiley.

- Bester, G (2007). "Personality development of the adolescent: peer group versus parents". South African Journal of Education. 27 (2): 177–90.

- McGue, M., Bouchard, T.J. Jr., Iacono, W.G. & Lykken, D.T. (1993). Behavioral genetics of cognitive stability: A life-span perspectiveness. In R. Plominix & G.E. McClearn (Eds.), Nature, nurture, and psychology (pp. 59-76). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Plomin, R.; Daniels, D. (1987). "Why are children in the same family so different from one another?". Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 10 (3): 1–16. doi:10.1017/s0140525x00055941. Reprinted in Plomin, R; Daniels, D (June 2011). "Why are children in the same family so different from one another?". Int J Epidemiol. 40 (3): 563–82. doi:10.1093/ije/dyq148. PMC 3147063. PMID 21807642.

- Plomin, R. (1990). Nature and nurture: An introduction to human behavioral genetics. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

- Grier, Peter (24 April 2000). "The Heart Of A High School: Peers As Collective Parent". Christian Monitor News Science: 1.

- Grier, Peter (24 April 2000). "The Heart Of A High School:Peers As Collective Parent". Christian Science Monitor News Service: 1.

- Moreland, Richard L.; Levine, John M. (1982). Socialization in Small Groups: Temporal Changes in Individual-Group Relations. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 15. pp. 137–92. doi:10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60297-X. ISBN 978-0120152155.

- Cromdal, Jakob (2011). "Gender as a practical concern in children's management of play participation". In S.A. Speer and E. Stokoe (ed.). Conversation and Gender. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 296–309.

- Macionis, Gerber, John, Linda (2010). Sociology 7th Canadian Ed. Toronto, Ontario: Pearson Canada Inc. p. 109

- Epstein, Marina; Ward, Monique L (2011). "Exploring parent-adolescent communication about gender: Results from adolescent and emerging adult samples". Sex Roles. 65 (1–2): 108–18. doi:10.1007/s11199-011-9975-7. PMC 3122487. PMID 21712963.

- Connell, R.W. (1987). Gender and power: society, the person and sexual politics. Stanford: Stanford Univ. Press. pp. 191–94. ISBN 978-0804714303.

- Rotherman, M., & Phinney, J. (1987). Introduction: Definitions and perspectives in the study of children's ethnic socialization. In J. Phinney & M. Rotherman (Eds.), Children's ethnic socialization: Pluralism and development (pp. 10-28). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

- Hughes, D.; Rodriguez, J.; Smith, E.; Johnson, D.; Stevenson, H.; Spicer, P. (2006). "Parents' ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study". Developmental Psychology. 42 (5): 747–770. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.525.3222. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747. PMID 16953684.

- Glasberg, Davita Silfen; Shannon, Deric (2011). Political sociology: Oppression, resistance, and the state. Thousand Oaks: Pine Forge Press. p. 47.

-

- Schieffelin, Bambi B.; Ochs, Elinor (1987). Language Socialization across Cultures. Volume 3 of Studies in the Social and Cultural Foundations of Language. Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521339197, 978-0521339193

- Schieffelin, Bambi B. (1990). The Give and Take of Everyday Life: Language, Socialization of Kaluli Children. P CUP Archive, ISBN 0521386543, 978-0521386548

- Duranti, Alessandro; Ochs, Elinor; Schieffelin, Bambi B. (2011). The Handbook of Language Socialization, Volume 72 of Blackwell Handbooks in Linguistics. John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 1444342886, 978-1444342888

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-10-25. Retrieved 2012-10-04.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Miller, Seumas (1 January 2014). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy – via Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Hurrelmann, Klaus (1989, reissued 2009). Social Structure and Personality Development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Hurrelmann, Klaus; Bauer, Ullrich (2018). Socialisation During the Life Course. London/New York: Routledge

- Wrong, Dennis H. (1 January 1961). "The Oversocialized Conception of Man in Modern Sociology". American Sociological Review. 26 (2): 183–93. doi:10.2307/2089854. JSTOR 2089854.

- Gintis, Herbert; van Schaik, Carel; Boehm, Christopher (June 2015). "Zoon Politikon: The Evolutionary Origins of Human Political Systems" (PDF). Current Anthropology. 56 (3): 327–53. doi:10.1086/681217.

- Searle, Jason (1 January 2015). "Traditional Economics and the Fiduciary Illusion: A Socio- Legal Understanding of Corporate Governance". Brigham Young University Prelaw Review. 29 (1). Retrieved 2 April 2017.

Further reading

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Socialization |

| Library resources about Socialization |

- Bayley, Robert; Schecter, Sandra R. (2003). Multilingual Matters, ISBN 1853596353, 978-1853596353

- Bogard, Kimber (2008). "Citizenship attitudes and allegiances in diverse youth". Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 14 (4): 286–96. doi:10.1037/1099-9809.14.4.286. PMID 18954164.

- Duff, Patricia A.; Hornberger, Nancy H. (2010). Language Socialization: Encyclopedia of Language and Education, Volume 8. Springer, ISBN 9048194660, 978-9048194667

- Kramsch, Claire (2003). Language Acquisition and Language Socialization: Ecological Perspectives – Advances in Applied Linguistics. Continuum International Publishing Group, ISBN 0826453724, 978-0826453723

- McQuail, Dennis (2005). McQuail's Mass Communication Theory: Fifth Edition, London: Sage.

- Mehan, Hugh (1991). Sociological Foundations Supporting the Study of Cultural Diversity. National Center for Research on Cultural Diversity and Second Language Learning.

- White, Graham (1977). Socialisation, London: Longman.

.svg.png)