Sirenomelia

Sirenomelia, also called mermaid syndrome, is a rare congenital deformity in which the legs are fused together, giving the appearance of a mermaid's tail, hence the nickname.

| Sirenomelia | |

|---|---|

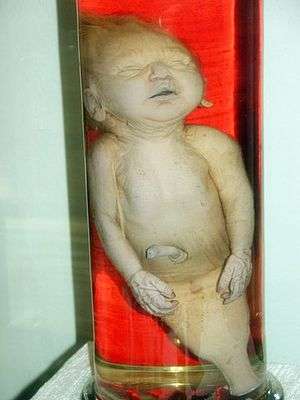

| |

| Sirenomelia, Lyon natural history and anatomy museum | |

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

Classification

Sirenomelia is classified by the skeletal structure of the lower limb, ranging from class I, where all bones are present and only the soft tissues are fused, to class VII where the only bone present is a fused femur.[1]

It has also been classified as an expanded part of the VACTERL association and as a form of caudal regression syndrome.[1][2][3]

Presentation

Sirenomelia is mainly characterized by the fusion of both legs with rotation of the fibula. It may include absence of the lower spine, abnormalities of the pelvis, renal organs, and was previously thought to be a severe form of sacral agensis/caudal regression syndrome, but more recently research verifies that these two conditions are not related.[4] NORD has a separate report on caudal regression syndrome. In general, the more severe cases of limb fusion correlate with more severe dysplasia in the pelvis. Rather than the two iliac arteries present in fetuses with complete renal agenesis, fetuses with sirenomelia display no branching of the abdominal aorta, which is always absent.[1]

Associated defects recorded in cases of sirenomelia include neural tube defects (rachischisis, anencephaly, and spina bifida), holoprosencephaly, hypoplastic left heart syndrome, other heart defects, esophageal atresia, omphalocele, intestinal malrotation, persistent cloaca, and other limb defects (most commonly absence of the radius).[1]

Causes

The ultimate cause of sirenomelia is a subject of debate. The first hypothesis of its origin was developed in 1927 and proposed that a lack of blood supply to the lower limbs during their development is responsible for the defect. This "vascular steal" hypothesis was developed in response to the observed absence or severe underdevelopment of the aorta below the umbilical artery, which "steals" the blood supply from the lower limbs. Other hypotheses involve an insult to the embryo between 28–32 days affecting the caudal mesoderm, a teratogen exposure affecting the neural tube during neurulation, and a defect in the twinning process that either stops the process of caudal differentiation or generates a second primitive streak.[1]

Maternal diabetes mellitus has been associated with caudal regression syndrome and sirenomelia,[5][6] although a few sources question this association.[7] Prenatal cocaine exposure has also been suggested as an association with sirenomelia.[1]

Diagnosis

Though obvious at birth, sirenomelia can be diagnosed as early as 14 weeks gestation on prenatal ultrasound. When there is low amniotic fluid around the fetus (oligohydramnios), the diagnosis is more difficult.[1]

Prognosis

Sirenomelia is usually fatal. Many pregnancies with a sirenomelic fetus spontaneously miscarry. One-third to one-half of infants are stillborn, with all but a few dying in the neonatal period.[1]

In cases of monoamniotic twins where one is affected, the twin with sirenomelia is protected from Potter sequence (particularly pulmonary hypoplasia and abnormal facies) by the normal twin's production of amniotic fluid.[11][1]

Epidemiology

This condition is found in approximately one out of every 100,000 live births; studies produce rates from 1 in 68,741 to 1 in 97,807.[1][12] It is 100 to 150 times more likely in identical (monozygotic) twins than in singletons or fraternal twins.[11][1] Sirenomelia is not associated with any ethnic background, but fetuses with sirenomelia are more likely to have testes.[1]

Etymology

The word sirenomelia derives from the ancient Greek word seirēn, referring to the mythological Sirens, who were sometimes depicted as mermaids, and melos, meaning "limb".

History

Sirenomelia was first reported in 1542. In 1927, Otto Kampmeier discovered the association between sirenomelia and single umbilical artery.[1]

Notable individuals

Only a few individuals who had some functioning kidney tissue have survived the neonatal period.[1]

Tiffany Yorks

Tiffany Yorks of Clearwater, Florida (May 7, 1988 – February 24, 2016)[13] underwent successful surgery in order to separate her legs before she was a year old.[14] She was the longest-surviving sirenomelia patient to date.[15] She suffered mobility issues due to her fragile leg bones, and compensated by using crutches or a wheelchair. She died on February 24, 2016 at the age of 27.

Shiloh Pepin

Shiloh Jade Pepin (August 4, 1999 – October 23, 2009) was born in Kennebunkport, Maine, United States with her lower extremities fused, no bladder, no uterus, no rectum, only 6 inches of large colon, no vagina, and with only one quarter of a kidney and one ovary. Her parents initially anticipated she could expect only a few months of life. At age 3, her natural kidney failed, and she began dialysis.[16] A kidney transplant at age 2 lasted a number of years, and in 2007 a second kidney transplant was successful. She attended Consolidated Elementary School. She remained hopeful about her disease and joked often and lived her life happily, despite her challenges, as seen in her TLC documentary in "Extraordinary People: Mermaid Girl". Shiloh and her family were debating surgery because of the risks involved, even though it would improve her quality of life. Many people who have this condition receive surgery when they are young, but Shiloh was already 8 years old in the documentary and had not received surgery. Shiloh was the only one of the three survivors of sirenomelia without surgery for separation of the conjoined legs.[17] She died of pneumonia on October 23, 2009, at Maine Medical Center in Portland, Maine, at the age of 10;[18] having appeared on the Oprah Winfrey Show on September 22, 2009.[19] Shiloh gained a following of admirers by documenting her condition on TV, Facebook, and the Internet.

Milagros Cerrón

Milagros Cerrón Arauco (April 27, 2004 - October 24, 2019) was born in Huancayo, Peru. Although most of Milagros’ internal organs, including her heart and lungs, are in perfect condition, she was born with serious internal defects, including a deformed left kidney and a very small right one located very low in her body. In addition, her digestive, urinary tracts and genitals share a single tube. This birth defect occurs during the gastrulation week (week 3) of embryonic development. Gastrulation establishes the three germ layers: ectoderm, mesoderm and endoderm. It seems that complications such as defects in the urogenital system as mentioned above can be possibly due to malformations in the intermediate mesoderm.

A four-hour operation to insert silicone bags between her legs to stretch the skin was successfully completed on February 8, 2005. A successful operation to separate her legs to just above the knee took place May 31, 2005, in a "Solidarity Hospital" in the district of Surquillo in Lima. The procedure, however, was so intensive that she became traumatized to the degree of losing her ability to form proper speech patterns, leaving her nearly mute. It is not yet known if this is a physiological or psychological condition. However, at Milagros' second birthday, her mother reported that she knew more than 50 words. A second operation to complete the separation up to the groin took place on September 7, 2006.[15]

Her doctor Luis Rubio said he was pleased with the progress Milagros had made, but cautioned that she still needed 10 to 15 years of rehabilitation and more operations before she could lead a normal life. Particularly, she will require reconstructive surgery to rebuild her rudimentary anus, urethra and genitalia.

Milagros' parents are from a poor village in Peru's Andes Mountains; the Solidarity Hospital has given a job to her father Ricardo Cerrón so that the family can remain in Lima, while the City of Lima has pledged to pay for many of the operations.[14]

References

- B., Holmes, Lewis (2011). Common malformations. Oxford: Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 9780199722785. OCLC 751694637.

- Onyeije, Chukwuma; Sherer, David; Handwerker, Sara; Shah, Leena (2008). "Prenatal Diagnosis of Sirenomelia with Bilateral Hydrocephalus: Report of a Previously Undocumented form of VACTERL-H Association". American Journal of Perinatology. 15 (3): 193–7. doi:10.1055/s-2007-993925. PMID 9572377.

- M., Carlson, Bruce (2014). Human embryology and developmental biology (5th ed.). Philadelphia, Pa.: Elsevier/Saunders. ISBN 9781455727971. OCLC 828737906.

- reference: https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/sirenomelia/ and Das BB, Rajegowda BK, Bainbridge R, Giampietro PF. Caudal regression syndrome versus sirenomelia: a case report. J Peritnatol. 2002;22:169-170)

- Peter D., Turnpenny (2017). Emery's elements of medical genetics. Ellard, Sian (Edition 15 ed.). [Philadelphia, Pa.]: Elsevier. ISBN 9780702066894. OCLC 965492903.

- Abraham M. Rudolph; Robert K. Kamei; Kim J. Overby (2002). Rudolph's Fundamentals of Pediatrics. McGraw Hill. p. 217. ISBN 978-0-8385-8450-7. Retrieved 2008-04-21.

- Assimakopoulos, E; Athanasiadis, A; Zafrakas, M; Dragoumis, K; Bontis, J (2004). "Caudal regression syndrome and sirenomelia in only one twin in two diabetic pregnancies". Clinical and Experimental Obstetrics & Gynecology. 31 (2): 151–3. PMID 15266776.

- "srn siren [ Mus musculus (house mouse) ]". NCBI Gene.

- "Twsg1 twisted gastrulation BMP signaling modulator 1 [ Mus musculus (house mouse) ]". NCBI Gene.

- "srn MGI Mouse Gene Detail - MGI:98421 - siren". www.informatics.jax.org. Retrieved 2018-10-19.

- Creasy and Resnik's maternal-fetal medicine : principles and practice. Creasy, Robert K.,, Resnik, Robert,, Greene, Michael F.,, Iams, Jay D.,, Lockwood, Charles J. (Seventh ed.). Philadelphia, PA. 2013-09-17. ISBN 9780323186650. OCLC 859526325.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Kallen, B; Castilla, E E; Lancaster, P A; Mutchinick, O; Knudsen, L B; Martinez-Frias, M L; Mastroiacovo, P; Robert, E (1992). "The cyclops and the mermaid: An epidemiological study of two types of rare malformation". Journal of Medical Genetics. 29 (1): 30–5. doi:10.1136/jmg.29.1.30. PMC 1015818. PMID 1552541.

- Tiffany Yorks [@TiffanyYorks] (24 February 2016). "This is Tiffanys cousin Jessica Tannehill. Tiffany passed away this morning after a hard fight and she stayed..." (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ""Mermaid" girl takes first steps". BBC News. 28 September 2006.

- ""Mermaid" girl's legs separated". BBC News. 7 September 2006.

- TV program Body Shock, 10–11 pm, 18 May 2010, Channel 4

- Sammons, Mary Beth (November 26, 2009). "10-Year-Old Girl Born With Legs Fused Together". AOL. Archived from the original on November 26, 2009.

- Laura Dolce (2009-10-23). "Community saddened at 'Mermaid girl' Shiloh Pepin's passing". SeacoastOnline.com. Retrieved 2011-12-01.

- "SHILOH PEPIN". The Oprah Show. oprah.com. May 16, 2011. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

In Memoriam: The Oprah Show has hosted a number of unforgettable guests over the years. Look back at some of those who are no longer with us.

- "Milagros, the "little mermaid girl", died at the age of 15". Vaaju. 24 October 2019.

- "Niña sirenita': fallece Milagros Cerrón Arauco a los 15 años". Diario El Comercio. 24 October 2019.

| Classification |

|---|