Sigurd Ring

Sigurd Ring (Old Norse: Sigurðr Hringr, in some sources merely called Hringr[1]) was a legendary king of the Swedes[2] mentioned in many old Scandinavian sagas. According to these sources he was granted rulership over Uppland as a vassal king under his uncle Harald Wartooth. Later he would take up arms against his uncle Harald in a bid to overthrow him and take the crown of Denmark, a conflict which Sigurd eventually won after the legendary Battle of the Brávellir, where it is said that Odin himself intervened and killed Harald. In the Sagas Sigurd is also known for being the father of the Norse Viking hero and legendary king of Denmark and Sweden, Ragnar Lodbrok. According to Bósa saga ok Herrauds, there was once a saga on Sigurd Ring, but this saga is now lost.[3] [4]

| Sigurd Ring | |

|---|---|

| Legendary king of Sweden and later possibly Denmark | |

| Reign | 8th century? |

| Predecessor | Harald Wartooth |

| Successor |

|

| Issue | Ragnar Lodbrok |

| House | House of Munsö |

| Father | Randver or Ingjald |

| Mother | Åsa Haraldsdotter or Harald Wartooth's sister |

| Religion | Old Norse religion |

Hervarar saga

The Hervarar saga tells that when the Danish tributary king Valdar died, his son Randver became the king of Denmark, while his older brother Harald Wartooth took royal titles in Gautland. Then Harald subjugated all the territories once ruled by his maternal grandfather Ivar Vidfamne (Sweden, Denmark, Curonia, Saxony, Estonia, Gardarike, Northumberland). After Randver's death in battle in England, his son Sigurd Ring became the king of Denmark, presumably as the subking of Harald. Sigurd Ring and Harald fought the Battle of the Brávellir (Bråvalla) on the plains of Östergötland where Harald and many of his men died. Sigurd Ring ruled Denmark until his death and was succeeded by his son Ragnar Lodbrok. Harald Wartooth, however, had a son called Eysteinn Illruler who ruled Sweden until he was killed by Björn Ironside, a son of Ragnar Lodbrok.[5]

Sögubrot af nokkrum fornkonungum

In Sögubrot af nokkrum fornkonungum, Ring (mostly mentioned without the name element Sigurd) is the paternal nephew of the Danish king Harald Wartooth, and presumably (the part of Sögubrot where this would have been narrated expressly has not been preserved) the son of Randver, who in his turn is the son of Harald's mother Auðr the Deep-Minded and her husband king Raðbarðr of Gardariki. Harald Wartooth was beginning to feel old, so he made Ring the king of Uppland, with the commission to rule Sweden and Västergötland. When Harald reached the extraordinary age of 150, he desired to die like a king in battle, and therefore challenged Ring to meet him in the field. Ring gathered manpower from Sweden, Västergötland and Norway and marched his troops by land and sea to the plain of Brávellir beneath the forest of Kolmården, close to the Bråviken bay. There he was met by the multi-ethic army of Harald, and the colossal Battle of Brávellir followed. In the end Ring beat his uncle, who was bludgeoned to death in the desperate fighting, and became the ruler of Denmark as well. He put an jarl in charge of Skåne and made a shieldmaiden the ruler of the rest of Denmark (cf. Chronicon Lethrense, below).[6]

Sigurd Ring (as he is now called in the text) married Alfhild, the daughter of king Alf of Álfheimr and their son was Ragnar Lodbrok. As Sigurd grew old, distant parts of his realm began to secede, and it is told how he lost territory in England due to old age. A certain Adalbrikt (Æthelberht) took possession of Northumbria and was succeeded by his sons Ama and Ælla. One day, Sigurd was in Västergötland and was visited by his in-laws, the sons of Gandalf. They asked him to join them in attacking king Eysteinn of Vestfold in Norway. In Vestfold, there were great blóts held at Skiringssal. Unfortunately, Sögubrot (meaning the "fragment") ends there. However, the Skjöldunga saga is believed to be the original story on which Sögubrot is based and it continues the story (see below).[7]

Olaf Tryggvason's saga

According to the extended Saga of Olaf Tryggvason, Sigurd Ring, after having stabilized his Swedish-Danish realm, recalled the lands in England once ruled by Harald Wartooth and Ivar Vidfamne. This territory was now ruled by Ingjald (Ingild), a brother of King Peter of Wessex and a mighty ruler in his own right. Ring therefore summoned the leiðangr and sailed to the west, reaching Northumbria. As Ingjald learned about the invasion, he gathered an army. In the ensuing battle, Ingjald and his son Ubbe (Eoppa) fell with a large part of their army. Ring now subordinated Northumbria and made Olaf Kinriksson tributary king. He was a grandnephew of Moald Digra, the mother of Ivar Vidfamne. Ring sailed back to his Nordic kingdom and Olaf reigned for a long time. Then, however, Eava (Eafa), the son of Ubbe, claimed the kingdom. Olaf was defeated and fled to his suzerain in Svíþióð. As compensation, Ring installed Olaf as sub-king in Jutland. As such he served Ring and later Ragnar Lodbrok. His descendants Grim, Audulf and Gorm (I) the Childless also ruled in Jutland. Gorm I adopted the foundling Knud, whose son Gorm II was the foster father of Hardeknud I, ancestor of the later Danish kings.[8] The saga refers to names found in Anglo-Saxon royal genealogies, ancestors of Ecgberht, King of Wessex.[9]

Skjöldunga saga

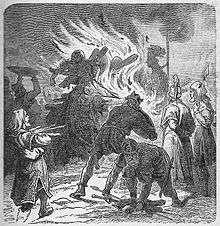

The Skjöldunga saga tells that Sigurd Ring was married to Alfhild, the daughter of king Alf of Alfheim, and their son was Ragnar Lodbrok. Unfortunately, Alfhild died. When Sigurd Ring was an old man, he came to Skiringssal to take part in the great blóts. There he spotted a very beautiful girl named Alfsol, and she was the daughter of King Alf of Vendel (Vendel). The girl's two brothers refused to allow Sigurd to marry her. Sigurd fought with the brothers and killed them, but their sister had been given poison by her brothers so that Sigurd could never have her. When her corpse was carried to Sigurd, he went aboard a large ship where he placed Alvsol and her brothers. Then, he steered the ship with full sails out on the sea, as the ship burnt.[10]

Ragnar Lodbrok succeeded his father, but put a subking on the throne of Sweden, king Eysteinn Beli, who later was killed by Ragnar's sons.

Gesta Danorum

According to Gesta Danorum (book 7), by Saxo Grammaticus, Ring was the son of the Swedish king Ingjald and the maternal nephew of the Danish king Harald Wartooth. His father Ingjald had ravished the sister of Harald, resulting in an indecisive spate of warfare. In the end Harald accepted the abduction in order preserve the friendship with Ingjald.[11] Ring fought with Harald Wartooth in the Battle of the Brávellir and became the overlord of Denmark as well. He appointed his cousin Ale the Strong as sub-king in Skåne while entrusting the shieldmaiden Hetha with the rest of the Danish lands.[12] Saxo then describes the different subkings and their adventures. Fourteen Danish kings later, in book 9, Saxo presents a Sigurd Ring as Siwardus, surnamed Ring. This king, however, bears no resemblance to the victor of Brávellir. Rather, he is the son of a Norwegian chief Sigurd and the maternal grandson of the historical King Götrik (i.e. Gudfred, d. 810). Backed by the men of Zealand and Skåne, he fights a civil war against his cousin Ring. As the two rivals join battle, they both fall. Sigurd Ring is the father of Ragnar Lodbrok who has been brought up in Norway during the civil war, but is now hailed as Danish ruler.[13]

Other sources

According to Hversu Noregr byggdist, Sigurd Ring is the son of Randver, the uterine brother of Harald Wartooth. Randver is the son of Raðbarðr while Harald is the son of Hrærekr slöngvanbaugi.[14]

In the part of the Heimskringla called the Saga of Harald Fairhair, Harald Fairhair learns that the Swedish king Erik Eymundsson had enlarged Sweden westwards, until it reached the same extent as it had during king Sigurd Ring and his son Ragnar Lodbrok. This included Romerike, Westfold all the way to Grenmar, and Vingulmark.[15]

In Ragnar Lodbrok's saga, it is mentioned that Sigurd Ring and Harald Wartooth fought in the Battle of the Brávellir and that Harald fell. After the battle Sigurd Ring was the king of Denmark, and he was the father of Ragnar Lodbrok.[16]

Ragnarssona þáttr only states that Ring was the king of Sweden and Denmark, and the father of Ragnar Lodbrok.[17]

In Bósa saga ok Herrauds, it is only said that Sigurd Ring, the father of Ragnar Lodbrok fought with Harald Wartooth at the Battle of the Brávellir where Harald died. It adds that there was a saga on Sigurd Ring (which today no longer exists).[18]

According to the Chronicon Lethrense, Harald Wartooth had made all the countries down to the Mediterranean pay tribute. However, when he went to Sweden to demand tribute, the Swedish king Ring met him at the Battle of the Brávellir, and Harald lost and died. Ring made a shieldmaiden the ruler of Denmark (cf. Sögubrot af nokkrum fornkonungum, above).[19]

Gríms saga loðinkinna and the younger version of Orvar-Odd's saga only mention Sigurd Ring in a few lines relating to the Battle of the Brávellir with Harald Wartooth.[20]

In Norna-Gests þáttr, it is said that Sigurd Ring was very old when he sent his son-in-law, the son of Gandalf, to request the Gjukungs, Gunnar and Högne to pay tribute. This was promptly refused. The sons of Gandalf then asked Sigurd Ring to help them fight against the Gjukungs and their renowned ally Sigurd Fafnisbani. Sigurd Ring could not help them in person, as he was busy fighting against ravaging Curonians and Kœnir.[21] Battle was joined in Holstein but turned into a defeat for the Norse army, since Sigurd Fanisbane made the Norse champion Starkad flee in panic.[22]

Historical origins

It has been suggested that a report of a struggle for the Danish crown may have given rise to the legend of Sigurd Ring. Following the death of Hemming in 812, a civil war broke out between his brother or cousin Sigifridus and Anulo. This Anulo was the nephew or grandson (nepos) of an earlier king Harald. The rivals fought a battle for the succession in which both were killed.[23] The names Sigfred and Sigurd were often conflated in medieval texts. As for Anulo, the name might originally represent Old Norse Ánleifr or Áli, though it was misunderstood by medieval Scandinavian chroniclers as Latin annulus which means ring.[24] Saxo Grammaticus and some other medieval compilers of king lists clearly combine the names Sigfred/Sigurd and Anulo/Ring into one person, having received knowledge of 9th century historical events from the chronicle of Adam of Bremen (c. 1075). Their historical successor Ragnfred (r. 812-813) is mixed up by Saxo with the Viking leader Ragnar Lodbrok, who is identified as the son of Sigurd Ring.[25] The Danish list of early Viking Age kings is therefore in part a High Medieval construction.[26]

One possibility is thus that the struggle of 812 is reflected in the legendary Battle of the Brávellir, fought by Sigurd Ring, nephew of Harald Wartooth.[27] Other scholars have suggested that the original name of the ruler was Ring, that he was a historical king of the Swedes, and that he won a battle against a Danish or East Geatic host in the 8th century.[28] Still others regard the battle as mythical or purely legendary.[29] Modern Swedish historians are skeptical to the prospects of establishing a chronology from the information of the High Medieval saga literature, and generally decline to discuss the possible historicity of Sigurd Ring or the Brávellir battle.[30]

The name Ring occurs in the royal Swedish clan in the Viking Age, since the ecclesiastic chronicle of Adam of Bremen (c. 1075) says that a ruler in the first half of the 10th century bore that name.[31]

Primary sources

- Bósa saga ok Herrauds

- Chronicon Lethrense

- Gesta Danorum

- Gríms saga loðinkinna

- Heimskringla (Saga of Harald Fairhair)

- Hervarar saga

- Hversu Noregr byggdist

- Norna-Gests þáttr

- Orvar-Odd's saga

- Ragnar Lodbrok's saga

- Ragnarssona þáttr

- Skjöldunga saga

- Sögubrot

Secondary sources

- Ellehøj, Svend (1965) Studier over den ældste norrøne historieskrivning. Hafniæ: Munksgaard.

- Harrison, Dick (2002) Sveriges historia: medeltiden. Stockholm: Liber.

- Jessen, C.A.E. (1862) Undersøgelser til nordisk oldhistorie. København: Otto Schwartz's Boghandel.

- Nerman, Birger (1925) Det svenska rikets uppkomst. Stockholm: Generalstabens Litografiska Anstalt [Föreningen för Svensk Kulturhistoria, Böcker, N:o 6].

- Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde, Vol. 13 (1999). Berlin: de Gruyter.

- Saga Ólafs Konúngs Tryggvasonar, Vol. 1 (1825). Copenhagen: Popp.

- Saxo Grammaticus (1905) The nine books of the Danish history of Saxo Grammaticus. London: Norroena Society

- Smyth, Alfred (1977) Scandinavian kings in the British Isles 850-880. Oxford.

- Storm, Gustav (1877) "Ragnar Lodbrok og Lodbrokssønnerne; Studie i dansk Oldhistorie of nordisk Sagnhistorie", Historisk Tidskrift 2:1

- Tolkien, Christopher, & Turville-Petre, G. (eds) (1956) Hervarar Saga ok Heidreks. London: Viking Society for Northern Research.

- Truhart, Peter (1988) Regents of nations, Vol. I-III. München: Saur.

References

- Namely, in Lejrekroniken, Gesta Danorum, and the Saga of Orvar-Odd; see Nerman (1925), p. 246-50.

- Katarina Harrison Lindbergh, Nordisk mytologi från A till Ö.

- Nerman (1925), p. 250.

- J. Butler, "The real Ragnar Lodbrok", Historic UK.

- Ellehøj (1965), p. 88-93; Tolkien & Turville-Petre (1956), p. 68,

- Nerman (1925), p. 246-8.

- Nerman (1925), p. 257-8.

- Saga Ólafs, Chapter 61, p. 110-1.

- Neither Ingild (d. 718), Olaf or Eafa are historically known to have reigned in Northumbria; Truhart (1988), Vol. III-2, p. 3549. Ingild's brother was King Ine of Wessex.

- Nerman (1925), p. 258-9.

- Saxo Grammaticus (1905), p. 459.

- Saxo Grammaticus (1905), p. 482-3.

- Saxo Grammaticus (1905), p. 539-41.

- Nerman (1925), p. 250.

- Nerman (1925), p. 259.

- Ragnars Saga Lodbrokar , p. 12.

- The Saga of Ragnar Lodbrok and His Sons

- Nerman (1925), p. 249-50.

- Nerman (1925), p. 250.

- Nerman (1925), p. 250.

- Nerman (1925), p. 259.

- The Story of Norna-Gest, Chapter 7

- Jessen (1862), p. 13-29.

- Storm (1877), p. 396.

- Storm (1877), p. 391-9.

- Smyth (1977), p. 1-4.

- Jessen (1862), p. 35.

- Nerman (1925), p. 256-7, 261.

- Reallexikon, Vol. 13 (1999), p. 645-7

- Harrison (2002), p. 23.

- Harrison (2002), p. 72.