Penalty kick (association football)

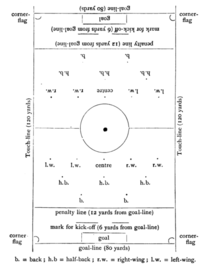

A penalty kick (commonly known as a penalty or a PK) is a method of restarting play in association football, in which a player is allowed to take a single shot on the goal while it is defended only by the opposing team's goalkeeper. It is awarded when a foul punishable by a direct free kick is committed by a player in their own penalty area. The shot is taken from the penalty mark, which is 11 m (12 yards) from the goal line and centred between the touch lines.

In practice, penalty kicks result in goals more often than not, even against the best and most experienced goalkeepers. This means that penalty awards are game-changing decisions and often decisive, particularly in low-scoring games.

Similar kicks are made in a penalty shootout in some tournaments to determine which team is victorious after a drawn match; these are governed by slightly different rules.

Procedure

The ball is placed on the penalty mark, regardless of where in the penalty area the foul occurred. The player taking the kick is to be identified to the referee. Only the kicker and the defending team's goalkeeper are allowed to be within the penalty area; all other players must be within the field of play but outside the penalty area, behind the penalty mark, and a minimum of 9.15m (10 yd) from the penalty mark (this distance is denoted by the penalty arc).[1] The goalkeeper must stand on the goal line between the goal posts until the ball is kicked. Lateral movement is allowed, but the goalkeeper is not permitted to come off the goal line by stepping or lunging forward until the ball is in play. The assistant referee responsible for the goal line where the penalty kick is being taken is positioned at the intersection of the penalty area and goal line, and assists the referee in looking for infringements and/or whether a goal is scored.

When the referee is satisfied that the players are properly positioned, they blow the whistle to indicate that the kicker may kick. The kicker may make feinting (deceptive or distracting) moves during the run-up to the ball, but once the run-up is completed they may no longer feint and must kick the ball. The ball must be stationary before the kick, and it must be kicked forward. The ball is in play once it is kicked and moves, and at that time other players may enter the penalty area. Once kicked, the kicker may not touch the ball again until it has been touched by another player of either team or goes out of play (including into the goal).

Infringements

.jpg)

In case of an infringement of the laws of the game during a penalty kick, most commonly entering the penalty area illegally, the referee must consider both whether the ball entered the goal, and which team(s) committed the offence.

| Result of the kick | No violation | Violation by the attacking team only | Violation by the defence only | Violation by both |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enters the goal | Goal | Rekick | Goal | Rekick |

| Goes directly out of bounds | Goal kick | Goal kick | Rekick | Rekick |

| Rebounds into play from goal frame/goalkeeper | Play continues | Indirect free kick | Rekick | Rekick |

| Saved & held by goalkeeper | Play continues | Play continues | Rekick | Rekick |

| Deflected out of bounds by goalkeeper | Corner kick | Indirect free kick | Rekick | Rekick |

The following infringements committed by the kicking team result in an indirect free kick for the defending team, regardless of the outcome of the kick:

- a teammate of the identified kicker kicks the ball instead (the player who took the kick is cautioned)

- kicker feints kicking the ball at the end of the run-up (the kicker is cautioned)

- kick does not go forward

- kicker touches the ball a second time before it touches another player (includes rebounds off the goal posts or crossbar)

In the case of a player repeatedly infringing the laws during the penalty kick, the referee may caution the player for persistent infringement. Note that all offences that occur before kick may be dealt with in this manner, regardless of the location of the offence.

If the ball touches an outside agent (i.e., an object foreign to the playing field) as it moves forward from the kick, the kick is retaken.

Tap penalty

A two-man penalty, or "tap" penalty, occurs when the kicker, instead of shooting for goal, taps the ball slightly forward so that a teammate can run on to it and shoot. If properly executed, it is a legal play since the kicker is not required to shoot for goal and need only kick the ball forward. This strategy relies heavily on the element of surprise, as it first requires the goalkeeper to believe the kicker will actually shoot, then dive or move to one side in response. It then requires the goalkeeper to remain out of position long enough for the kicker's teammate to reach the ball before any defenders, and for that teammate to place a shot on the undefended side of the goal.

The first recorded tap penalty was taken by Jimmy McIlroy and Danny Blanchflower of Northern Ireland against Portugal on 1 May 1957.[2] Another was taken by Rik Coppens and André Piters in the World Cup Qualifying match Belgium v Iceland on 5 June 1957. Another attempt was made by Mike Trebilcock and John Newman, playing for Plymouth Argyle in 1964.[3] Later on, Johan Cruyff tried the same with his Ajax team-mate Jesper Olsen in 1982.[3]

Arsenal players Thierry Henry and Robert Pires failed in an attempt at a similar penalty in 2005, during a Premier League match against Manchester City at Highbury. Pires ran in to take the kick, attempted to pass to the onrushing Henry, but miskicked and the ball hardly moved; as he had slightly touched the ball, he could not touch it again, and City defender Sylvain Distin cleared the ball before Henry could shoot.[4]

Lionel Messi tapped a penalty for Luis Suárez as Suárez completed his hat-trick on 14 February 2016 against league opponents Celta de Vigo.[5]

Saving tactics

"Reading" the kicker

Defending against a penalty kick is one of the most difficult tasks a goalkeeper can face. Owing to the short distance between the penalty spot and the goal, there is very little time to react to the shot. Because of this, the goalkeeper will usually start his or her dive before the ball is actually struck. In effect, the goalkeeper must act on his best prediction about where the shot will be aimed. Some goalkeepers decide which way they will dive beforehand, thus giving themselves a good chance of diving in time. Others try to read the kicker's motion pattern. On the other side, kickers often feign and prefer a relatively slow shot in an attempt to foil the goalkeeper. The potentially most fruitful approach, shooting high and centre, i.e., in the space that the goalkeeper will evacuate, also carries the highest risk of shooting above the bar.

As the shooter makes his approach to the ball, the goalkeeper has only a fraction of a second to "read" the shooter's motions and decide where the ball will go. If their guess is correct, this may result in a missed penalty. Helmuth Duckadam, Steaua București's goalkeeper, saved a record four consecutive penalties in the 1986 European Cup Final against Barcelona. He dived three times to the right and a fourth time to his left to save all penalties taken, securing victory for his team.

Use of knowledge of kicker's history

A goalkeeper may also rely on knowledge of the shooter's past behaviour to inform his decision. An example of this would be by former Netherlands national team goalkeeper Hans van Breukelen, who always had a box with cards with all the information about the opponent's penalty specialist. Ecuadorian goalkeeper Marcelo Elizager saving a penalty from Carlos Tevez in a match between Ecuador and Argentina, revealed that he had studied some penalty kicks from Tévez and suspected he was going to shoot to the goalkeeper's left side. Two other examples occurred during the 2006 FIFA World Cup:

- Portugal national team goalkeeper Ricardo in a quarter-final match against England, where he saved three penalties out of four.

- The quarter-final match between Argentina and Germany also came down to penalties, and German goalkeeper Jens Lehmann was seen looking at a piece of paper kept in his sock before each Argentinian player would come forward for a penalty kick. It is presumed that information on each kicker's "habits" were written on this paper. Lehmann saved two of the four penalties taken and came close to saving a third.

This approach may not always be successful; the player may intentionally switch from his favoured spot after witnessing the goalkeeper obtaining knowledge of his kicks. Most times, especially in amateur football, the goalkeeper is often forced to guess. Game theoretic research shows that both the penalty taker and also the goalkeeper must randomize their strategies in precise ways to avoid having the opponent take advantage of their predictability.[6]

Distraction

The goalkeeper also may try to distract the penalty taker, as the expectation is on the penalty taker to succeed, hence more pressure on the penalty taker, making them more vulnerable to mistakes. For example, in the 2008 UEFA Champions League Final between Manchester United and Chelsea, United goalkeeper Edwin van der Sar pointed to his left side when Nicolas Anelka stepped up to take a shot in the penalty shoot out. This was because all of Chelsea's penalties went to the left. Anelka's shot instead went to Van der Sar's right, which was saved. Liverpool goalkeeper Bruce Grobbelaar used a method of distracting the players called the "spaghetti legs" trick to help his club defeat Roma to win the 1984 European Cup. This tactic was emulated in the 2005 UEFA Champions League Final, which Liverpool also won, by Liverpool goalkeeper Jerzy Dudek, helping his team defeat Milan.

An illegal method of saving penalties is for the goalkeeper to make a quick and short jump forward just before the penalty taker connects with the ball. This not only shuts down the angle of the shot, but also distracts the penalty taker. The method was used by Brazilian goalkeeper Cláudio Taffarel. FIFA was less strict on the rule during that time. In more recent times, FIFA has advised all referees to strictly obey the rule book.

Similarly, a goalkeeper may also attempt to delay a penalty by cleaning his boots, asking the referee to see if the ball is placed properly and other delaying tactics. This method builds more pressure on the penalty taker, but the goalkeeper may risk punishments, most likely a yellow card.

A goalkeeper can also try to distract the taker by talking to them prior to the penalty being taken. Netherlands national team goalkeeper Tim Krul used this technique during the penalty shootout in the quarter-final match of the 2014 FIFA World Cup against Costa Rica. As the Costa Rican players were preparing to take the kick, Krul told them that he ''knew where they were going to put their penalty'' in order to ''get in their heads''.[7] This resulted in him saving two penalties and the Netherlands winning the shootout 4–3.

Under new IFAB rule changes, if the penalty taker attempts to feint or dummy the opposing goalkeeper after completing the run-up to the ball, the taker will be punished with a yellow card, and will not be allowed to retake the kick.[8][9]

Scoring statistics

Even if the goalkeeper succeeds in blocking the shot, the ball may rebound back to the penalty taker or one of his teammates for another shot, with the goalkeeper often in a poor position to make a second save. This makes saving penalty kicks more difficult. This is not a concern in penalty shoot-outs, where only a single shot is permitted.

While penalty kicks are considerably more often successful than not, missed penalty kicks are not uncommon: for instance, of the 78 penalty kicks taken during the 2005–06 English Premier League season, 57 resulted in a goal, thus almost 30% of the penalties were unsuccessful.[10]

A German professor who has been studying penalty statistics in the German Bundesliga for 16 years found 76% of all the penalties during those 16 years went in, and 99% of the shots in the higher half of the goal went in, although the higher half of the goal is a more difficult target to aim at. During his career, Italian striker Roberto Baggio had two occurrences where his shot hit the upper bar, bounced downwards, rebounded off the keeper and passed the goal line for a goal.

Saving statistics

Some goalkeepers have become well known for their ability to save penalty kicks. One such goalkeeper is Brazilian goalkeeper Diego Alves, who boasts a 49 percent save success rate. Other goalkeepers with high save rates include Claudio Bravo, Kevin Trapp, Samir Handanovic, Gianluigi Buffon, Tim Krul, Danijel Subasic, and Manuel Neuer.[11][12]

Offences for which the penalty kick is awarded

A penalty kick is awarded whenever one of the following offences is committed by a player within that player's own penalty area while the ball is in play (note that the ball must be in play at the time of the offence, but it does not need to be within the penalty-area at that time).[13][14]

- handball (excluding handling offences committed by the goalkeeper)[15]

- any of the following offences against an opponent, if committed in a manner considered by the referee to be careless, reckless or using excessive force:[15]

- charges

- jumps at

- kicks or attempts to kick

- pushes

- strikes or attempts to strike (including head-butt)

- tackles or challenges

- trips or attempts to trip

- holding an opponent[16]

- impeding an opponent with contact[16]

- biting or spitting at someone[16]

- throwing an object at the ball, an opponent or a match official, or making contact with the ball with a held object[16]

- any physical offence, if committed within the penalty area while the ball is in play, against a team-mate, substitute, substituted or sent-off player, team official or a match official[17]

- a player who requires the referee's permission to re-enter the field of play, substitute, substituted player, sent-off player, or team official enters the field of play without the referee's permission, and interferes with play[18]

- a player who requires the referee's permission to re-enter the field of play, substitute, substituted player, sent-off player or team official is on the field of play without the referee's permission while that person's team scores a goal[19]

- a player temporarily off the field of play, substitute, substituted player, sent-off player or team official throws or kicks an object onto the field of play, and the object interferes with play, an opponent, or a match official.[20]

History

Early proposals

The original laws of the game, in 1863, had no punishments for infringements of the rules.[21] In 1872, the indirect free kick was introduced as a punishment for illegal handling of the ball; it was later extended to other offences.[22] This indirect free-kick was thought to be an inadequate remedy for a handball which prevented an otherwise-certain goal.[23] As a result of this, in 1882 a law was introduced to award a goal to a team prevented from scoring by an opponent's handball. This law lasted only one season before being abolished in 1883.

Introduction of the penalty-kick

The invention of the penalty kick is credited to the goalkeeper and businessman William McCrum in 1890 in Milford, County Armagh, Ireland.[24] The Irish Football Association presented the idea to the International Football Association Board's 1890 meeting, where it was deferred until the next meeting in 1891.[25]

Two incidents in the 1890–1 season lent additional force to the argument for the penalty kick. On 20 December 1890, in the Scottish Cup quarter-final between East Stirlingshire and Heart of Midlothian Jimmy Adams[26] fisted the ball out from under the bar,[27][28] and on 14 February 1891, there was a blatant goal-line handball by a Notts County player in the FA Cup quarter-final against Stoke City

Finally after much debate, the International Football Association Board approved the idea on 2 June 1891.[29][30] The penalty-kick law ran:

If any player shall intentionally trip or hold an opposing player, or deliberately handle the ball, within twelve yards [11 m] from his own goal-line, the referee shall, on appeal, award the opposing side a penalty kick, to be taken from any point twelve yards [11 m] from the goal-line, under the following conditions:— All players, with the exception of the player taking the penalty kick and the opposing goalkeeper (who shall not advance more than six yards [5.5 m] from the goal-line) shall stand at least six yards [5.5 m] behind the ball. The ball shall be in play when the kick is taken, and a goal may be scored from the penalty kick.[31]

Some notable differences between this original 1891 law and today's penalty-kick are listed below:

- It was awarded for an offence committed within 12 yards (11 m) of the goal-line (the penalty area was not introduced until 1902).

- It could be taken from any point along a line 12 yards (11 m) from the goal-line (the penalty spot was likewise not introduced until 1902).

- It was awarded only after an appeal.

- There was no restriction on dribbling.

- The ball could be kicked in any direction.

- The goal-keeper was allowed to advance up to 6 yards (5.5 m) from the goal-line.

The world's first penalty kick was awarded to Airdrieonians in 1891 at Broomfield Park,[32] and the first penalty kick in the Football League was awarded to Wolverhampton Wanderers in their match against Accrington at Molineux Stadium on 14 September 1891. The penalty was taken and scored by "Billy" Heath[33] as Wolves went on to win the game 5–0.

Subsequent developments

.png)

In 1892, the player taking the penalty-kick was forbidden to kick the ball again before the ball had touched another player. A provision was also added that "[i]f necessary, time of play shall be extended to admit of the penalty kick being taken".[34]

In 1896, the ball was required to be kicked forward, and the requirement for an appeal was removed.[35]

In 1902, the penalty area was introduced with its current dimensions (a rectangle extending 18 yards (16 m) from the goal-posts). The penalty spot was also introduced, 12 yards (11 m) from the goal. All other players were required to be outside the penalty area.[36]

In 1905, the goal-keeper was required to remain on the goal-line.[37]

In 1923, all other players were required to be at least 10 yards (9.15 m) from the penalty-spot (in addition to being outside the penalty-area).[38] This change was made in order to stop defenders from lining up on the edge of the penalty area to impede the player taking the kick.[39]

In 1930, a footnote was appended to the laws, stating that "the goal-keeper must not move his feet until the penalty kick has been taken".[40]

In 1937, an arc (colloquially known as the "D") was added to the pitch markings, to assist in the enforcement of the 10-yard (9.15 m) restriction.[41] The goal-keeper was required to stand between the goal-posts.[42]

In 1939, it was specified that the ball must travel the distance of its circumference before being in play.[43] In 1997, this requirement was eliminated: the ball became in play as soon as it was kicked and moved forward.[44] In 2016, it was specified that the ball must "clearly" move.[45]

In 1995, all other players were required to remain behind the penalty spot. The Scottish Football Association claimed that this new provision would "eliminate various problems which have arisen regarding the position of players who stand in front of the penalty-mark at the taking of a penalty-kick as is presently permitted".[46]

In 1997, the goal-keeper was once again allowed to move the feet, and was also required to face the kicker.[47]

The question of "feinting" during the run-up to a penalty has occupied the International FA Board since 1982, when it decided that "if a player stops in his run-up it is an offence for which he shall be cautioned (for ungentlemanly conduct) by the referee".[48] However, in 1985 the same body reversed itself, deciding that the "assumption that feigning was an offence" was "wrong", and that it was up to the Referee to decide whether any instance should be penalized as ungentlemanly conduct.[49] From 2000 to 2006, documents produced by IFAB specified that feinting during the run-up to a penalty-kick was permitted.[50] In 2007, this guidance emphasized that "if in the opinion of the referee the feinting is considered an act of unsporting behaviour, the player shall be cautioned".[51] In 2010, because of concern over "an increasing trend in players feinting a penalty kick to deceive the goalkeeper", a proposal was adopted to specify that while "feinting in the run-up to take a penalty kick to confuse opponents is permitted as part of football", "feinting to kick the ball once the player has completed his run-up is considered an infringement of Law 14 and an act of unsporting behaviour for which the player must be cautioned".[52]

Summary

| Date | Location of offence | Location of penalty-kick | Position of goal-keeper | Position of other players | Goal-keeper may move feet | Taker may kick ball twice | Ball may be kicked backward | Kicker may feint | Goal may be scored | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1891 | Within 12 yards (11 m) of the goal-line | From any point 12 yards (11 m) from the goal-line | Within 6 yards (5.5 m) of the goal-line | At least 6 yards (5.5 m) behind the ball | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unless considered ungentlemanly behaviour | Yes | 1891 |

| 1892 | No | 1892 | ||||||||

| 1896 | No | 1896 | ||||||||

| 1902 | Within the penalty area | From the penalty spot | Within the goal area | Outside the penalty area | 1902 | |||||

| 1905 | On the goal line | 1905 | ||||||||

| 1923 | Outside the penalty area, and at least 10 yards (9.15 m) from the ball | 1923 | ||||||||

| 1930 | No | 1930 | ||||||||

| 1937 | On the goal line between the posts | 1937 | ||||||||

| 1982 | No | 1982 | ||||||||

| 1985 | Unless considered ungentlemanly / unsporting behaviour | 1985 | ||||||||

| 1995 | Outside the penalty area, at least 10 yards (9.15 m) from the ball, and behind the ball | 1995 | ||||||||

| 1997 | Yes | 1997 | ||||||||

| 2010 | Unless the run-up is complete | 2010 | ||||||||

Offences for which a penalty kick was awarded

Since its introduction in 1891, a penalty kick has been awarded for two broad categories of offences:

- handball

- serious offences involving physical contact

The number of offences eligible for punishment by a penalty-kick, small when initially introduced in 1891, expanded rapidly thereafter. This led to some confusion: for example, in September 1891, a referee awarded a penalty kick against a goalkeeper who "[lost] his temper and [kicked] an opponent", even though under the 1891 laws this offence was punishable only by an indirect free-kick.[53]

The table below shows the punishments[54] specified by the laws for offences involving handling the ball or physical contact, between 1890 and 1903:[55]

| Date | Handball | Tripping | Pushing | Holding | Kicking a player | Jumping at a player | Charging from behind[56] | Technical handling violations by the goalkeeper[57] | Dangerous play[58] | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1890 | Indirect free-kick | Indirect free-kick | Indirect free-kick | Indirect free-kick | Indirect free-kick | Indirect free-kick | Indirect free-kick | Indirect free-kick | Not prohibited | 1890 |

| 1891 | Indirect free-kick / Penalty-kick | Indirect free-kick / Penalty-kick | Indirect free-kick / Penalty-kick | 1891 | ||||||

| 1893 | Indirect free-kick / Penalty-kick | Indirect free-kick | 1893 | |||||||

| 1897 | Indirect free-kick / Penalty-kick | 1897 | ||||||||

| 1901 | Indirect free-kick / Penalty-kick | 1901 | ||||||||

| 1902 | Indirect free-kick / Penalty-kick | 1902 | ||||||||

| 1903 | Direct free-kick / Penalty-kick | Direct free-kick / Penalty-kick | Direct free-kick / Penalty-kick | Direct free-kick / Penalty-kick | Direct free-kick / Penalty-kick | Direct free-kick / Penalty-kick | Direct free-kick / Penalty-kick | 1903 | ||

Since 1903, the offences for which a penalty kick is awarded within the defending team's penalty area have been identical to those for which a direct free kick is awarded outside the defending team's penalty area. These consisted of handball (excluding technical handling offences by the goalkeeper), and foul play, with the following exceptions (which were punished instead by an indirect free kick in the penalty area):[59]

References

- "Laws of the Game 2019/20" (PDF). p. 38.

- "Video: Messi who? Northern Ireland legends Blanchflower and McIlroy's brilliant penalty". Independent.ie.

- "Lionel Messi penalty: Robert Pires and Thierry Henry, Johan Cruyff and Jesper Olsen and others to try trick penalties". Independent. 15 February 2016.

- "Wenger defends Pires over penalty". BBC News. 22 October 2005.

- "Messi passes from penalty for Suárez's hat-trick as Barça beats Celta 6–1". Wikinews. 15 February 2016.

- Testing Mixed-Strategy Equilibria When Players Are Heterogeneous: The Case of Penalty Kicks in Soccer, 1 September 2002, JSTOR 3083302

- "Tim Krul: How the 120th-minute substitute stole Dutch glory". BBC Sport. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- Ough, Tom. "Five changes to the football rulebook that will affect Euro 2016 and beyond". The Telegraph. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- Murray, Les. "The madness of football's rule changes". The World Game. Special Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- Archived 13 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Ellis, Tim (30 January 2017). "9 of football's best penalty-saving goalkeepers". Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- Smith, Adam (5 October 2016). "Top penalty-stoppers in the Premier League and Europe". Sky Sports. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- Laws of the Game 2019/20, passim; see esp. p. 103

- Laws of the Game 2019/20, p. 87

- Laws of the Game 2019/20, p. 103

- Laws of the Game 2019/20, p. 104

- Laws of the Game 2019/20, p. 114

- Laws of the Game 2019/20, p. 53

- Laws of the Game 2019/20, p. 54

- Laws of the Game 2019/20, p. 115

- – via Wikisource.

- – via Wikisource.

- For example: "Windsor Home Park v Maidenhead". Bell's Life in London: 8. 23 November 1872.

F. Heron made a splendid shot at goal, which must have succeeded had not one of the Maidenhead men (not the goalkeeper) most unfairly stopped it with his hands. Of course the free kick ensued, but by this time the Maidenhead men had completely lined their goal, and, after a little scrimmage, Goolden succeeded in getting the ball away

- Daily Telegraph Monday 9 April 2007 p5 (see article on Telegraph online)

- "International Football Association Board: 1890 Minutes of the Annual General Meeting" (PDF). p. 2. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- James Adams – A Squad, Scottish Football Association.

- "1890-12-20 Sat East Stirlingshire 1 Hearts 3".

- "1890122015 Hearts and Scottish Football Reports For Sat 20 Dec 1890 Page 15 of 22".

- The Sunday Times Illustrated History of Football Reed International Books Limited. 1996. p11. ISBN 1-85613-341-9

- "International Football Association Board: 1891 Minutes of the Annual General Meeting" (PDF). pp. 2–5. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- – via Wikisource.

- "Airdrie".

- "Happened on this day – 14 September". BBC News. 14 September 2002. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- – via Wikisource.

- – via Wikisource.

- – via Wikisource.

- – via Wikisource.

- "International Football Association Board: 1923 Minutes of the Annual General Meeting" (PDF). p. 2. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- "Penalty Kicks: A Practice that Must be Discontinued". Athletic News: 6. 4 June 1924.

- "International Football Association Board: 1930 Minutes of the Annual General Meeting" (PDF). p. 4. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- "International Football Association Board: 1937 Minutes of the Annual General Meeting" (PDF). p. 6. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- "International Football Association Board: 1937 Minutes of the Annual General Meeting" (PDF). p. 6. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- "International Football Association Board: 1939 Minutes of the Annual General Meeting" (PDF). p. 4. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- "International Football Association Board: 1997 Minutes of the Annual General Meeting" (PDF). p. 135. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- "IFAB: Law Changes 2016-17" (PDF). p. 43. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- "International Football Association Board: 1995 Minutes of the Annual General Meeting" (PDF). p. 38. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- "International Football Association Board: 1997 Minutes of the Annual General Meeting" (PDF). p. 135. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- "International Football Association Board: 1982 Minutes of the Annual General Meeting" (PDF). p. 6. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- "International Football Association Board: 1985 Minutes of the Annual General Meeting" (PDF). p. 24. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- e.g. "The Laws of the Game: Questions and Answers: 2006" (PDF). p. 37. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- "Laws of the Game 2007/2008" (PDF). p. 125. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- "Amendments to the Laws of the Game – 2010/2011" (PDF). p. 4. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- "En Passant". Athletic News and Cyclists' Journal. xiii (835): 1. 21 September 1891.

- excluding caution / sending-off

- "Charging the goalkeeper" is excluded, since it could never occur within 12 yards of the opponents' goal-line

- Subject to certain exceptions: see the individual editions of the laws for details

- Taking more than two steps while holding the ball in own half; also, before 1901, handling the ball in own half for a purpose other than defence of the keeper's goal.

- Between 1892 and 1901, also "play[ing] in any manner likely to cause injury"

- Offences which could only be committed against the goalkeeper in his/her own penalty area are excluded from this list, since they could not lead to a penalty kick; see the free kick article for further detail.

- – via Wikisource.

A goal may be scored from a free kick which is awarded because of any infringement of Law 9, but not from any other free kick.

- "International Football Association Board: 1951 Minutes of the Annual General Meeting" (PDF). p. 3.

the following new offence to be punished by an indirect free-kick: (3) When not playing the ball, intentionally obstructing an opponent

- In 2016, impeding an opponent with contact was made a direct free kick / penalty kick offence

- "Laws of the Game 2016/17" (PDF). p. 82. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- "International Football Association Board: 1948 Minutes of the Annual General Meeting" (PDF). p. 5.

CHARGES FAIRLY ... WHEN THE BALL IS NOT WITHIN PLAYING DISTANCE OF THE PLAYERS CONCERNED AND THEY ARE DEFINITELY NOT ATTEMPTING TO PLAY IT

- In 1997, this was abolished as a separate offence; all forms of charging an opponent "in a manner considered by the referee to be careless, reckless, or involving excessive force" became punishable by a direct free-kick

External links

![]()