Shackleton Limestone

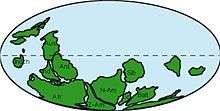

The Shackleton Limestone is a Cambrian limestone formation of the Byrd Group of Antarctica. The age of the formation is established to be Cambrian Stage 3, dated at ranging from 520 to 516 Ma. This period correlates with the End-Botomian mass extinction. Fossils of trilobites and Marocella mira and Dailyatia have been found in the formation, named after Ernest Shackleton, who led a failed expedition into Antarctica. At time of deposition, the Antarctic Plate has been established to be just south of the equator as part of the supercontinent Pannotia, contrasting with its present position at 82 degrees southern latitude.[1]

| Shackleton Formation Stratigraphic range: Cambrian Stage 3 ~520–516 Ma | |

|---|---|

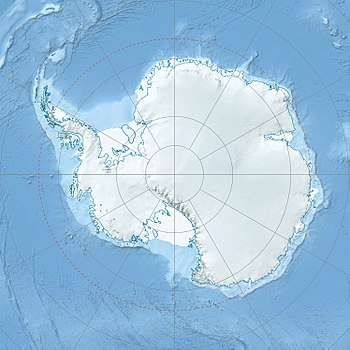

Shackleton Limestone (Antarctica) | |

| Type | Geological formation |

| Unit of | Byrd Group |

| Underlies | Starshot Formation |

| Overlies | Goldie Formation |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | Limestone, marble, sandstone |

| Other | Quartzite, conglomerate, shale, dolomite |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 82.2°S 160.3°W |

| Approximate paleocoordinates | 0.7°S 155.4°W |

| Region | Churchill Mountains of Antarctica |

| Type section | |

| Named for | Ernest Shackleton |

| Named by | Laird |

| Year defined | 1963 |

Paleogeography of the Cambrian with the supercontinent Pannotia and Antarctica south of the paleo-equator | |

Geology

The formation, named by Laird in 1963, crops out in the Churchill Mountains, part of the Transantarctic Mountains of southwestern Antarctica. The most complete exposures are in the Holyoake Range.[2] Paleontological data and carbon isotope stratigraphy indicate that the Shackleton Limestone ranges from lower Atdabanian through upper Botomian. The formation is a thick carbonate deposit with a lower unit of unfossiliferous interbedded quartzite and limestone, overlies the Late Proterozoic argillaceous turbidite Goldie Formation and underlies the Starshot Formation.[2][3] Other lithologies noted in the Shackleton Limestone are marble with breccia, conglomerate, sandstone and shale.[4] The abrupt transition from the Shackleton Limestone to a large-scale, upward coarsening siliciclastic succession records deepening of the outer platform and then deposition of an eastward-prograding molassic wedge. The various formations of the upper Byrd Group show general stratigraphic and age equivalence, such that coarse-grained alluvial fan deposits of the Douglas Conglomerate are proximal equivalents of the marginal-marine to shelf deposits of the Starshot Formation.[5]

The sandstone-rich lower member of the Shackleton Limestone is exposed at Cotton Plateau beneath Panorama Point, where it consists of up to 133 metres (436 ft) of interbedded white- to cream-weathering, vitreous, quartz sandstone and brown-weathering, white, fine-grained dolomitic grainstone. These beds are in fault contact with the adjacent Goldie Formation.[6] The formation postdates the Beardmore Orogeny of the Neoproterozoic,[7] and was deformed by the Ross Orogeny.[8]

Fossil content

The formation has provided fossils of trilobites such as Holyoakia granulosa, Pagetides (Discomesites) spinosus, Lemdadella antarcticae, Kingaspis (?) convexus, Yunnanocephalus longioccipitalis, and Onchocephalina (?) spinosa.[9] Other fossils found are Marocella mira,[1] and Dailyatia odyssei and D. braddocki.[10]

See also

References

- Shackleton Limestone at Fossilworks.org

- Myrow et al., 2002, p.1073

- Rowell, A.J.; Rees, M.N. (1991). Thomson, M.R.A.; Crame, J.A.; Thomson, J.W. (eds.). Setting and significance of the Shackleton Limestone, central Transantarctic Mountains, in Geological Evolution of Antarctica. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 171–175. ISBN 9780521372664.

- Laird et al., 1971, p.428

- Myrow et al., 2002, p.1070

- Myrow et al., 2002, p.1075

- Elliot, 1975, p.54

- Stump et al., 2006, p.2

- Palmer & Rowell, 1995

- Skovsted, 2015, p.16

Bibliography

- Elliot, David H. 1975. Tectonics of Antarctica: A Review. American Journal of Science 275-A. 45–106. Accessed 2018-05-22.

- Laird, M.G.; G.D. Mansergh, and J.M.A. Chappell. 1971. Geology of the Central Nimrod Glacier area, Antarctica. New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics 17. 427–468. Accessed 2018-05-22.

- Myrow, Paul M.; Michael C. Pope; John W. Goodge; Woodward Fischer, and Alison R. Palmer. 2002. Depositional history of pre-Devonian strata and timing of Ross orogenic tectonism in the central Transantarctic Mountains, Antarctica. GSA Bulletin 114. 1070–1088. Accessed 2018-05-22.

- Palmer, A.R., and A.J. Rowell. 1995. Early Cambrian trilobites from the Shackleton Limestone of the Central Mountains. Journal of Paleontology Memoir 69. 1–28. Accessed 2018-05-22.

- Skovsted, Christian B.; Marissa J. Betts; Timothy P. Topper, and Glenn A. Brock. 2015. The early Cambrian tommotiid genus Dailyatia from South Australia. AAP Memoir 48. 1–117. Accessed 2018-05-22.

- Gootee, Brian, and Franco Talarico. 2006. Tectonic Model for Development of the Byrd Glacier Discontinuity and Surrounding Regions of the Transantarctic Mountains during the Neoproterozoic – Early Paleozoic, 45–54. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York. Accessed 2018-05-22.