Selk'nam genocide

The Selk'nam genocide was the genocide of the Selk'nam people, one of three indigenous tribes populating the Tierra del Fuego in South America, from the second half of the 19th to the early 20th century. The genocide spanned a period of between ten and fifteen years. The Selk'nam, which had an estimated population of 4,000 people, saw their numbers reduced to 500.[2]

| Selk'nam genocide | |

|---|---|

| Part of Genocide of indigenous peoples | |

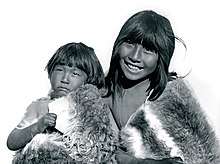

Julius Popper standing next to an unclothed slaughtered Selk'nam and his firing squad. | |

| Location | Tierra del Fuego, Argentina and Chile |

| Date | late 19th to early 20th century |

Attack type | Genocidal massacre, Internment, Bounty killings |

| Deaths | 3,900[1] (97.5% of the population killed) |

| Victims | Selk'nam tribe |

| Perpetrators | Julius Popper and his exploring company Ramón Lista and his detachment of soldiers José Menéndez and the Sociedad Explotadora de Tierra del Fuego |

| Motive | Utilitarian genocide |

Background

The Selk'nam were one of three indigenous tribes who inhabited the northeastern part of the archipelago, with a population before the genocide estimated at between 3,000 and 4,000.[3] They were known as the Ona (people of the north), by the Yaghan (Yamana).[4]

The Selk'nam had lived a semi-nomadic life of hunting and gathering in Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego[5] for thousands of years. The name of the island literally means "big island of Land of the Fire", which is the name the early Spanish explorers gave it as they saw the smoke from Selk'nam bonfires.[5] They lived in the northeast, with the Haush people to their east on the Mitre Peninsula, and the Yaghan people to the west and south, in the central part of the main island and throughout the southern islands of the archipelago.

According to one study, the Selk'nam were divided into the following groups:[6]

- Parika (located in the Northern Pampas).

- Herska (located in the southern forests)

- Chonkoyuka (located in the mountains in front of Inútil Bay), alongside the Haush.

History

The last full-blooded Selk'nam, Ángela Loij, died in 1974. They were one of the last aboriginal groups in South America to be reached by Europeans. According to the 2010 United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger, the Ona language, believed to be part of the Chonan family, is considered extinct, as the last speakers died in the 1980s.[7]

About 4,000 Selk'nam were alive in the mid-nineteenth century; by 1930 this had been reduced to about 100. With the assimilation of many groups who later became Argentinians, Chileans, Selk'nam territory was conquered. The group's seemingly unusual ritual practices were frightening to many colonizers, which caused an unhealthy fear of their presence, and thereby offered a justification for their mass extinction.

The natives were plied with alcohol, deported, raped, and exterminated, with bounties paid to the most ruthless hunters.[1] Martin Gusinde, who visited the island towards the end of 1918, recounted in his writings that the hunters "sent the skulls of the murdered Indians to the Anthropological Museum in London, which paid four pounds per head."[8]

German anthropologist Robert Lehmann-Nitsche published the first scholarly studies of the Selk’nam, although he was later criticized for having studied members of the Selk’nam people who had been abducted and were exhibited in circuses in conditions of de facto slavery.[9]

The gold rush

The Chilean expedition of Ramón Serrano Montaner in 1879, was the one who reported the presence of important gold deposits in the sands of the main rivers of Tierra del Fuego. With this incentive, hundreds of foreign adventurers came to the island hoping to find long-awaited and distant lands, the initial support to produce auspicious fortunes.[10] However, there was a rapid depletion of the metal.

Among hunters of the indigenous people were Julius Popper, Alexander McLennan,[11] a "Mister Bond", Alexander A. Cameron, Samuel Hyslop, John McRae, and Montt E. Wales.[12][13]

Ranchers and farmers

The large ranchers tried to run off the Selk'nam, then began a campaign of extermination against them, with the compliance of the Argentine and Chilean governments. Large companies paid sheep farmers or militia a bounty for each Selk'nam dead, which was confirmed on presentation of a pair of hands or ears, or later a complete skull. They were given more for the death of a woman than a man. In addition, missionaries disrupted their livelihood through forcible relocation and inadvertently brought with them deadly epidemics.

Repression against the Selk'nam persisted into the early twentieth century.[14] Chile moved some Selk'nam to Dawson Island, confining them in an internment or concentration camp. Argentina finally allowed Salesian missionaries to aid the Selk'nam and attempt to assimilate them, with their traditional culture and livelihoods then completely interrupted.

See also

- Fuegians

- Ramon Lista

- Julius Popper

- Sociedad Explotadora de Tierra del Fuego

- Tierra del Fuego Gold Rush

- Selk'nam

References

- Gardini, Walter (1984). "Restoring the Honour of an Indian Tribe-Rescate de una tribu". Anthropos. 79 (4/6): 645–47. JSTOR 40461884.

- Chapman 2010, p. 544.

- Prieto 2007.

- Chapman2010, p. XX.

- Gilbert 2014.

- Chile Precolombino (ed.). "PUEBLOS ORIGINARIOS > SELK'NAM" (in Spanish). Retrieved 24 July 2019.

- Adelaar 2010, p. 92.

- Riquelme, Cristhian; Bratti, Simón. "Recopilación etnológica de una identidad étnica". Revista del Departamento Sociología y Antropología Antropología de los pueblos indígenas. Universidad de Concepción Chile. Retrieved 24 July 2019.

- Ballestero, Diego (2013). Los espacios de la antropología en la obra de Robert Lehmann-Nitsche, 1894-1938 (PhD). Universidad Nacional de La Plata.

- Spears, John (1895). The Gold Diggings of Cape Horn. A study of Life in Tierra del Fuego and Patagonia. New York. ISBN 9-7805-4834-724-9.

- Kelly, James. "In Search of Paradise Lost in Tierra del Fuego". Earth Island Journal. Earth Island Institute. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- According to Federico Echelaite's memoirs in the documentary film Los onas, vida y muerte en Tierra del Fuego (by A. Montes, A. Chapman, and J. Prelorán).

- Gusinde, Martin (1951). Hombres primitivos en la Tierra del Fuego (de investigador a compañero de tribu). Sevilla: Escuela de Estudios Hispano-Americanos de Sevilla. pp. 98–99. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- Adelaar 2010, p. 92.

Bibliography

- Adelaar, Willem (2010). "South America". In Moseley, Christopher (ed.). Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger (3rd Revised ed.). UNESCO. pp. 86–94. ISBN 978-9231040962.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Prieto, Alfredo (2007). "The Struggle for Social Life in Fuego Patagonia". In Chacon, Edward (ed.). Latin American Indigenous Warfare and Ritual Violence. University of Arizona Press. p. 213. ISBN 978-0816525270.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chapman, Anne (2010). European Encounters with the Yamana People of Cape Horn, Before and After Darwin (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521513791.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gilbert, Jérémie (2014). Nomadic Peoples and Human Rights. Routledge. p. 23. ISBN 978-0415526968.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Luis Alberto Borrero, Los Selk'nam (Onas), Galerna, Buenos Aires 2007.

- Lucas Bridges, Uttermost Part of the Earth, London 1948.

External links

- Montes de Gonzales, Ana; Chapman, Anne (1977). "Los Onas: vida y muerte en Terra del Fuego" (YouTube). El Comite Argentino del film Antropologico.

- Genocide In Chile: A Monument Is Not Enough