Scarlet fever

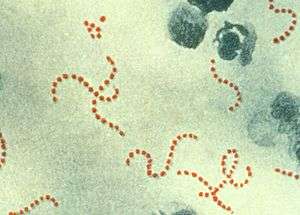

Scarlet fever is a disease resulting from a group A streptococcus (group A strep) infection, also known as Streptococcus pyogenes.[1] The signs and symptoms include a sore throat, fever, headaches, swollen lymph nodes, and a characteristic rash.[1] The rash is red and feels like sandpaper and the tongue may be red and bumpy.[1] It most commonly affects children between five and 15 years of age.[1]

| Scarlet fever | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Scarlatina,[1] scarletina[2] |

| Strawberry tongue seen in scarlet fever | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Sore throat, fever, headaches, swollen lymph nodes, characteristic rash[1] |

| Complications | Glomerulonephritis, rheumatic heart disease, arthritis[1] |

| Usual onset | 5–15 years old[1] |

| Causes | Strep throat, streptococcal skin infections[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Throat culture[1] |

| Prevention | Handwashing, not sharing personal items, staying away from sick people[1] |

| Treatment | Antibiotics[1] |

| Prognosis | Typically good[3] |

Scarlet fever affects a small number of people who have strep throat or streptococcal skin infections.[1] The bacteria are usually spread by people coughing or sneezing.[1] It can also be spread when a person touches an object that has the bacteria on it and then touches their mouth or nose.[1] The characteristic rash is due to the erythrogenic toxin, a substance produced by some types of the bacterium.[1][4] The diagnosis is typically confirmed by culturing the throat.[1]

There is no vaccine.[1] Prevention is by frequent handwashing, not sharing personal items, and staying away from other people when sick.[1] The disease is treatable with antibiotics, which prevent most complications.[1] Outcomes with scarlet fever are typically good if treated.[3] Long-term complications as a result of scarlet fever include kidney disease, rheumatic heart disease, and arthritis.[1] In the early 20th century, before antibiotics were available, it was a leading cause of death in children.[5][6]

Signs and symptoms

Rash which has a characteristic appearance, spreading pattern, and desquamating process "Strawberry tongue"

- The tongue initially has a white coating on it, while the papillae of the tongue are swollen and reddened. The protrusion of the red papillae through the white coating gives the tongue a "white strawberry" appearance.

- A few days later (following the desquamating process, or the shedding of the tissue which created the white coating), the whiteness disappears, and the red and enlarged papillae give the tongue the "red strawberry" appearance.[7] The symptomatic appearance of the tongue is part of the rash that is characteristic of scarlet fever.[8]

- Pastia's lines[9]

- Lines of petechiae, which appear as pink/red areas located in arm pits and elbow pits

- Vomiting and abdominal pain[10]

Strep throat

Typical symptoms of streptococcal pharyngitis (also known as strep throat):[10]

- Sore throat, painful swallowing

- Fever - typically over 39 °C (102.2 °F)

- Fatigue

- Enlarged and reddened tonsils with yellow or white exudates present (this is typically an exudative pharyngitis)[11]

- Enlarged and tender lymph nodes usually located on the front of the neck[12]

The following symptoms will usually be absent: cough, hoarseness, runny nose, diarrhea, and conjunctivitis.[10] Such symptoms indicate what is more likely a viral infection.

Rash

The rash begins 1–2 days following the onset of symptoms caused by the strep pharyngitis (sore throat, fever, fatigue).[13] This characteristic rash has been denoted as "scarlatiniform," and it appears as a diffuse redness of the skin with small papules, or bumps, which resemble goose bumps.[7][14] These bumps are what give the characteristic sandpaper texture to the rash. The reddened skin will blanch when pressure is applied to it. The skin may feel itchy, but it will not be painful.[7] The rash generally starts at the flexion of the elbow and other surfaces.[15] It appears next on the trunk and gradually spreads out to the arms and legs.[14] The palms, soles and face are usually left uninvolved by the rash. The face, however, is usually flushed, most prominently in the cheeks, with a ring of paleness around the mouth.[16] After the rash spreads, it becomes more pronounced in creases in the skin, such as the skin folds in the inguinal and axillary regions of the body.[9] Also in those areas, Pastia's Lines may appear: petechiae arranged in a linear pattern.[9] Within 1 week of onset, the rash begins to fade followed by a longer process of desquamation, or shedding of the outer layer of skin. This lasts several weeks.[12] The desquamation process usually begins on the face and progresses downward on the body.[7] After the desquamation, the skin will be left with a sunburned appearance.[13]

Mouth

The streptococcal pharyngitis, which is the usual presentation of scarlet fever in combination with the characteristic rash, commonly involves the tonsils. The tonsils will appear swollen and reddened. The palate and uvula are also commonly affected by the infection. The involvement of the soft palate can be seen as tiny red and round spots known as Forchheimer spots.[11]

Variable presentations

The features of scarlet fever can differ depending on the age and race of the person. Children less than 5 years old can have atypical presentations. Children less than 3 years old can present with nasal congestion and a lower grade fever.[17] Infants may present with symptoms of increased irritability and decreased appetite.[17]

Children who have darker skin can have a different presentation, as the redness of the skin involved in the rash and the ring of paleness around the mouth can be less obvious.[7] Suspicion based on accompanying symptoms and diagnostic studies are important in these cases.

Course

Following exposure to streptococcus, onset of symptoms occur 12 hours to 7 days later. These may include fever, fatigue, and sore throat. The characteristic scarlatiniform rash appears 12–48 hours later. During the first few days of the rash development and rapid generalization, the Pastia's Lines and strawberry tongue are also present.[7] The rash starts fading within 3–4 days, followed by the desquamation of the rash, which lasts several weeks to a month.[13][11] If the case of scarlet fever is uncomplicated, recovery from the fever and clinical symptoms, other than the process of desquamation, occurs in 5–10 days.[18]

Complications

The complications, which can arise from scarlet fever when left untreated or inadequately treated, can be divided into two categories: suppurative and nonsuppurative.

Suppurative complications: These are rare complications that arise either from direct spread to structures that are close to the primary site of infection, or spread through the lymphatic system or blood. In the first case, scarlet fever may spread to the pharynx. Possible problems from this method of spread include peritonsillar or retropharyngeal abscesses, cellulitis, mastoiditis or sinusitis.

In the second case, the streptococcal infection may spread through the lymphatic system or the blood to areas of the body further away from the pharynx. A few examples of the many complications that can arise from those methods of spread include endocarditis, pneumonia, or meningitis.[16]

Nonsuppurative complications: These complications arise from certain subtypes of group A streptococci that cause an autoimmune response in the body through what has been termed molecular mimicry. In these cases, the antibodies which the person's immune system developed to attack the group A streptococci are also able to attack the person's own tissues. The following complications result, depending on which tissues in the person's body are targeted by those antibodies.[14]

- Acute rheumatic fever: This is a complication that results 2–6 weeks after a group A streptococcal infection of the upper respiratory tract.[13] It presents in developing countries, where antibiotic treatment of streptococcal infections is less common, as a febrile illness with several clinical manifestations, which are organized into what is called the Jones criteria. These criteria include arthritis, carditis, neurological issues, and skin findings. Diagnosis also depends on evidence of a prior group A streptococcal infection in the upper respiratory tract (as seen in streptococcal pharyngitis and scarlet fever). The carditis is the result of the immunologic response targeting the person's heart tissue, and it is the most serious sequelae that develops from acute rheumatic fever. When this involvement of the heart tissue occurs, it is called rheumatic heart disease. In most cases of rheumatic heart disease, the mitral valve is affected, ultimately leading to mitral stenosis.[17]

- Poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis: This is inflammation of the kidney, which presents 1–2 weeks after a group A streptococcal pharyngitis. It can also develop after an episode of Impetigo or any group A streptococcal infection in the skin (this differs from acute rheumatic fever which only follows group A streptococcal pharyngitis).[13][19] It is the result of the autoimmune response to the streptococcal infection affecting part of the kidney. Persons present with what is called acute nephritic syndrome, in which they have high blood pressure, swelling, and urinary abnormalities. Urinary abnormalities include blood and protein found in the urine, as well as less urine production overall.[13]

- Poststreptococcal reactive arthritis: The presentation of arthritis after a recent episode of group A streptococcal pharyngitis raises suspicion for acute rheumatic fever, since it is one of the Jones criteria for that separate complication. But, when the arthritis is an isolated symptom, it is referred to as poststreptococcal reactive arthritis. This arthritis can involve a variety of joints throughout the body, unlike the arthritis of acute rheumatic fever, which primarily affects larger joints such as the knee joints. It can present less than 10 days after the group A streptococcal pharyngitis.[13]

Cause

Strep throat spreads by close contact among people, via respiratory droplets (for example, saliva or nasal discharge).[13] A person in close contact with another person infected with group A streptococcal pharyngitis has a 35% chance of becoming infected.[17] One in ten children who are infected with group A streptococcal pharyngitis will develop scarlet fever.[12]

Pathophysiology

The rash of scarlet fever, which is what differentiates this disease from an isolated group A strep pharyngitis (or strep throat), is caused by specific strains of group A streptococcus which produce a pyrogenic exotoxin.[13] These toxin-producing strains cause scarlet fever in people who do not already have antitoxin antibodies. Streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxins A, B, and C (speA, speB, and speC) have been identified. The pyrogenic exotoxins are also called erythrogenic toxins and cause the erythematous rash of scarlet fever.[13] The strains of group A streptococcus that cause scarlet fever need specific bacteriophages in order for there to be pyrogenic exotoxin production. Specifically, bacteriophage T12 is responsible for the production of speA.[20] Streptococcal Pyrogenic Exotoxin A, speA, is the one which is most commonly associated with cases of scarlet fever which are complicated by the immune-mediated sequelae acute rheumatic fever and post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis.[11]

These toxins are also known as “superantigens” because they are able to cause an extensive immune response within the body through activation of some of the main cells responsible for the person's immune system.[18] The body responds to these toxins by making antibodies to those specific toxins. However, those antibodies do not completely protect the person from future group A streptococcal infections, because there are 12 different pyrogenic exotoxins possible.[13]

Microbiology

The disease is caused by secretion of pyrogenic exotoxins by the infecting Streptococcus bacteria.[21][22] Streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin A (speA) is probably the best studied of these toxins. It is carried by the bacteriophage T12 which integrates into the streptococcal genome from where the toxin is transcribed. The phage itself integrates into a serine tRNA gene on the chromosome.[23]

The T12 virus itself has not been placed into a taxon by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. It has a double-stranded DNA genome and on morphological grounds appears to be a member of the Siphoviridae.

The speA gene was cloned and sequenced in 1986.[24] It is 753 base pairs in length and encodes a 29.244 kiloDalton (kDa) protein. The protein contains a putative 30- amino-acid signal peptide; removal of the signal sequence gives a predicted molecular weight of 25.787 kDa for the secreted protein. Both a promoter and a ribosome binding site (Shine-Dalgarno sequence) are present upstream of the gene. A transcriptional terminator is located 69 bases downstream from the translational termination codon. The carboxy terminal portion of the protein exhibits extensive homology with the carboxy terminus of Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxins B and C1.

Streptococcal phages other than T12 may also carry the speA gene.[25]

Diagnosis

Although the presentation of scarlet fever can be clinically diagnosed, further testing may be required to distinguish it from other illnesses.[7] Also, history of a recent exposure to someone with strep throat can be useful in diagnosis.[13] There are two methods used to confirm suspicion of scarlet fever; rapid antigen detection test and throat culture.[17]

The rapid antigen detection test is a very specific test but not very sensitive. This means that if the result is positive (indicating that the group A strep antigen was detected and therefore confirming that the person has a group A strep pharyngitis), then it is appropriate to treat the patient with antibiotics. But, if the rapid antigen detection test is negative (indicating that they do not have group A strep pharyngitis), then a throat culture is required to confirm, as the first test could have yielded a false negative result.[26] In the early 21st century, the throat culture is the current "gold standard" for diagnosis.[17]

Serologic testing seeks evidence of the antibodies that the body produces against the streptococcal infection, including antistreptolysin-O and antideoxyribonuclease B. It takes the body 2–3 weeks to make these antibodies, so this type of testing is not useful for diagnosing a current infection. But, it is useful when assessing a person who may have one of the complications from a previous streptococcal infection.[12][17]

Throat cultures done after antibiotic therapy can show if the infection has been removed. These throat swabs, however, are not indicated, because up to 25% of properly treated individuals can continue to carry the streptococcal infection while being asymptomatic.[19]

Differential diagnosis

- Viral exanthem: Viral infections are often accompanied by a rash which can be described as morbilliform or maculopapular. This type of rash is accompanied by a prodromal period of cough and runny nose in addition to a fever, indicative of a viral process.[14]

- Allergic or contact dermatitis: The erythematous appearance of the skin will be in a more localized distribution rather than the diffuse and generalized rash seen in scarlet fever.[12]

- Drug eruption: These are potential side effects of taking certain drugs such as penicillin. The reddened maculopapular rash which results can be itchy and be accompanied by a fever.[27]

- Kawasaki disease: Children with this disease also present a strawberry tongue and undergo a desquamative process on their palms and soles. However, these children tend to be younger than 5 years old, their fever lasts longer (at least five days), and they have additional clinical criteria (including signs such as conjunctival redness and cracked lips), which can help distinguish this from scarlet fever.[28]

- Toxic shock syndrome: Both streptococcal and staphylococcal bacteria can cause this syndrome. Clinical manifestations include diffuse rash and desquamation of the palms and soles. It can be distinguished from scarlet fever by low blood pressure, lack of sandpaper texture for the rash, and multi-organ system involvement.[29]

- Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome: This is a disease that occurs primarily in young children due to a toxin-producing strain of the bacteria Staphylococcus aureus. The abrupt start of the fever and diffused sunburned appearance of the rash can resemble scarlet fever. However, this rash is associated with tenderness and large blister formation. These blisters easily pop, followed by causing the skin to peel.[30]

- Staphylococcal scarlet fever: The rash is identical to the streptococcal scarlet fever in distribution and texture, but the skin affected by the rash will be tender.[7]

Prevention

One method is long-term use of antibiotics to prevent future group A streptococcal infections. This method is only indicated for people who have had complications like recurrent attacks of acute rheumatic fever or rheumatic heart disease. Antibiotics are limited in their ability to prevent these infections since there are a variety of subtypes of group A streptococci that can cause the infection.[13]

The vaccine approach has a greater likelihood of effectively preventing group A streptococcal infections because vaccine formulations can target multiple subtypes of the bacteria.[13] A vaccine developed by George and Gladys Dick in 1924 was discontinued due to poor efficacy and the introduction of antibiotics. Difficulties in vaccine development include the considerable strain variety of group A streptococci present in the environment and the amount of time and number of people needed for appropriate trials for safety and efficacy of any potential vaccine.[31] There have been several attempts to create a vaccine in the past few decades. These vaccines, which are still in the development phase, expose the person to proteins present on the surface of the group A streptococci to activate an immune response that will prepare the person to fight and prevent future infections.[32]

There used to be a diphtheria scarlet fever vaccine.[33] It was, however, found not to be effective.[34] This product was discontinued by the end of World War II.

Treatment

Antibiotics to combat the streptococcal infection are the mainstay of treatment for scarlet fever. Prompt administration of appropriate antibiotics decreases the length of illness. Peeling of the outer layer of skin, however, will happen despite treatment.[7] One of the main goals of treatment is to prevent the child from developing one of the suppurative or nonsuppurative complications, especially acute rheumatic fever.[17] As long as antibiotics are started within nine days, it is very unlikely for the child to develop acute rheumatic fever.[13] Antibiotic therapy has not been shown to prevent the development of post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis.[14][7] Another important reason for prompt treatment with antibiotics is the ability to prevent transmission of the infection between children. An infected individual is most likely to pass on the infection to another person during the first 2 weeks.[19] A child is no longer contagious (able to pass the infection to another child) after 24 hours of antibiotics.[13]

The antibiotic of choice is penicillin V which is taken by mouth in pill form. Children who are not able to take pills can be given amoxicillin which comes in a liquid form and is equally effective. Duration of treatment is 10 days.[17] Benzathine Penicillin G can be given as a one time intramuscular injection as another alternative if swallowing pills is not possible.[35] If the person is allergic to the family of antibiotics which both penicillin and amoxicillin are a part of (beta-lactam antibiotics), a first generation cephalosporin is used.[26] Cephalosporin antibiotics, however, can still cause adverse reactions in people whose allergic reaction to penicillin is a Type 1 Hypersensitivity reaction. In those cases it is appropriate to choose clindamycin or erythromycin instead.[26] Tonsillectomy, although once a reasonable treatment for recurrent streptococcal pharyngitis, is not indicate, as a person can still be infected with group A streptococcus without their tonsils.[19]

Antibiotic resistance

A drug-resistant strain of scarlet fever, resistant to macrolide antibiotics such as erythromycin, but retaining drug-sensitivity to beta-lactam antibiotics such as penicillin, emerged in Hong Kong in 2011, accounting for at least two deaths in that city—the first such in over a decade.[36] About 60% of circulating strains of the group A streptococcus that cause scarlet fever in Hong Kong are resistant to macrolide antibiotics, says Professor Kwok-yung Yuen, head of Hong Kong University's microbiology department. Previously, observed resistance rates had been 10–30%; the increase is likely the result of overuse of macrolide antibiotics in recent years.

Epidemiology

Scarlet fever occurs equally in both males and females.[12] Children are most commonly infected, typically between 5–15 years old. Although streptococcal infections can happen at any time of year, infection rates peak in the winter and spring months, typically in colder climates.[13]

The morbidity and mortality of scarlet fever has declined since the 18th and 19th century when there were epidemics caused by this disease.[37] Around 1900 the mortality rate in multiple places reached 25%.[38] The improvement in prognosis can be attributed to the use of penicillin in the treatment of this disease.[10] The frequency of scarlet fever cases has also been declining over the past century. There have been several reported outbreaks of the disease in various countries in the past decade.[39] The reason for these recent increases remains unclear in the medical community. Between 2013 and 2016 population rates of scarlet fever in England increased from 8.2 to 33.2 per 100,000 and hospital admissions for scarlet fever increased by 97%.[40]

History

It is unclear when a description of this disease was first recorded.[41] Hippocrates, writing around 400 BC, described the condition of a person with a reddened skin and fever.[42]

The first description of the disease in the medical literature appeared in the 1553 book De Tumoribus praeter Naturam by the Sicilian anatomist and physician Giovanni Filippo Ingrassia, where he referred to it as rossalia. He also made a point to distinguish that this presentation had different characteristics to measles.[42] It was redescribed by Johann Weyer during an epidemic in lower Germany between 1564 and 1565; he referred to it as scalatina anginosa. The first unequivocal description of scarlet fever appeared in a book by Joannes Coyttarus of Poitiers, De febre purpura epidemiale et contagiosa libri duo, which was published in 1578 in Paris. Daniel Sennert of Wittenberg described the classical 'scarlatinal desquamation' in 1572 and was also the first to describe the early arthritis, scarlatinal dropsy, and ascites associated with the disease.

In 1675 the term that has been commonly used to refer to scarlet fever, "scarlatina", was written by Thomas Sydenham, an English physician.[42]

In 1827, Richard Bright was the first to recognize the involvement of the renal system in scarlet fever.

The association between streptococci and disease was first described in 1874 by Theodor Billroth, discussing people with skin infections.[42] Billroth also coined the genus name Streptococcus. In 1884 Friedrich Julius Rosenbach edited the name to its current one, Streptococcus pyogenes, after further looking at the bacteria in the skin lesions.[42] The organism was first cultured in 1883 by the German surgeon Friedrich Fehleisen from erysipelas lesions.

Also in 1884, the German physician Friedrich Loeffler was the first to show the presence of streptococci in the throats of people with scarlet fever. Because not all people with pharyngeal streptococci developed scarlet fever, these findings remained controversial for some time. The association between streptococci and scarlet fever was confirmed by Alphonse Dochez and George and Gladys Dick in the early 1900s.[43]

Nil Filatov (in 1895) and Clement Dukes (in 1894) described an exanthematous disease which they thought was a form of rubella, but in 1900, Dukes described it as a separate illness which came to be known as Dukes' disease,[44] Filatov's disease, or fourth disease. However, in 1979, Keith Powell identified it as in fact the same illness as the form of scarlet fever which is caused by staphylococcal exotoxin and is known as staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome.[45][46][47][48]

Scarlet fever serum from horses' blood was used in the treatment of children beginning in 1900 and reduced mortality rates significantly.

In 1906, the Austrian pediatrician Clemens von Pirquet postulated that disease-causing immune complexes were responsible for the nephritis that followed scarlet fever.[49]

Bacteriophages were discovered in 1915 by Frederick Twort. His work was overlooked and bacteriophages were later rediscovered by Felix d'Herelle in 1917. The specific association of scarlet fever with the group A streptococci had to await the development of Lancefield's streptococcal grouping scheme in the 1920s. George and Gladys Dick showed that cell-free filtrates could induce the erythematous reaction characteristic of scarlet fever, proving that this reaction was due to a toxin. Karelitz and Stempien discovered that extracts from human serum globulin and placental globulin can be used as lightening agents for scarlet fever and this was used later as the basis for the Dick test. The association of scarlet fever and bacteriophages was described in 1926 by Cantucuzene and Boncieu.[50]

An antitoxin for scarlet fever was developed in 1924.

The first toxin which causes this disease was cloned and sequenced in 1986 by Weeks and Ferretti.[24] The discovery of penicillin and its subsequent widespread use has significantly reduced the mortality of this once feared disease. Reports of cases of scarlet fever have been on the rise in countries including England, Wales, South Korea, Vietnam, China, and Hong Kong in recent years. Researchers are unsure as to what has caused the spike in cases of the disease.[51][52]

The Dick test

The Dick test, invented in 1924 by George F. Dick and Gladys Dick, was used to identify those susceptible to scarlet fever.[53] The Dick test consisted of injecting a diluted strain of the streptococci known to cause scarlet fever into a person's skin. A local reaction in the skin at the site of injection appeared in people who were susceptible to developing scarlet fever. This reaction was most notable around 24 hours after the injection but could be seen as early as 4–6 hours. If there is no reaction seen in the skin, then that person was assumed to have already developed immunity to the disease and was not at risk of developing it.[54]

.jpg) Otto Kalischer wrote a doctoral thesis on scarlet fever in 1891.

Otto Kalischer wrote a doctoral thesis on scarlet fever in 1891._(8211297109).jpg) A 1930s American poster attempting to curb the spread of such diseases as scarlet fever by regulating milk supply

A 1930s American poster attempting to curb the spread of such diseases as scarlet fever by regulating milk supply.jpg) Gladys Henry Dick (pictured) and George Frederick Dick developed an antitoxin and vaccine for scarlet fever in 1924 which were later eclipsed by penicillin in the 1940s.

Gladys Henry Dick (pictured) and George Frederick Dick developed an antitoxin and vaccine for scarlet fever in 1924 which were later eclipsed by penicillin in the 1940s.

References

- "Scarlet Fever: A Group A Streptococcal Infection". Center for Disease Control and Prevention. 19 January 2016. Archived from the original on 12 March 2016. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- Shorter Oxford English dictionary. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. 2007. p. 3804. ISBN 978-0199206872.

- Quinn, RW (1989). "Comprehensive review of morbidity and mortality trends for rheumatic fever, streptococcal disease, and scarlet fever: the decline of rheumatic fever". Reviews of Infectious Diseases. 11 (6): 928–53. doi:10.1093/clinids/11.6.928. PMID 2690288.

- Ralph, AP; Carapetis, JR (2013). Group a streptococcal diseases and their global burden. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. 368. pp. 1–27. doi:10.1007/82_2012_280. ISBN 978-3-642-36339-9. PMID 23242849.

- Smallman-Raynor, Matthew (2012). Atlas of epidemic Britain : a twentieth century picture. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 48. ISBN 9780199572922. Archived from the original on 14 February 2017.

- Smallman-Raynor, Andrew Cliff, Peter Haggett, Matthew (2004). World Atlas of Epidemic Diseases. London: Hodder Education. p. 76. ISBN 9781444114195. Archived from the original on 14 February 2017.

- Zitelli, Basil; McIntire, Sara; Nowalk, Andrew (2018). Zitelli and Davis' Atlas of Pediatric Physical Diagnosis. Elsevier, Inc.

- Ferri, Fred (2018). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2018. Elsevier. p. 1143.

- Goldman, Lee; Schafer, Andrew (2016). Goldman-Cecil Medicine. Saunders. pp. 1906–1913.

- Wessels, Michael R. (2016). Ferretti, Joseph J.; Stevens, Dennis L.; Fischetti, Vincent A. (eds.). Streptococcus pyogenes : Basic Biology to Clinical Manifestations. Oklahoma City (OK): University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center. PMID 26866221.

- Goldsmith, Lowell; Katz, Stephen; Gilchrist, Barbara; Paller, Amy; Leffell, David; Wolff, Klaus (2012). Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. McGraw Hill.

- Usatine, Richard (2013). Color Atlas of Family Medicine, Second Edition. McGraw Hill Companies.

- Kliegman, Robert; Stanton, Bonita; St Geme, Joseph; Schor, Nina (2016). Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. Elsevier. pp. 1327–1337.

- Kaspar, Dennis; Fauci, Anthony; Hauser, Stephen; Longo, Dan; Jameson, J. Larry; Loscalzo, Joseph (2015). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 19th edition. McGraw Hill Education.

- Family Practice Guidelines, Third Edition. Springer Publishing Company. 2014. p. 525. ISBN 9780826168757.

- Bennett, John; Dolin, Raphael; Blaser, Martin (2015). Mandell, Douglas and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Disease, Eighth Edition. Saunders. pp. 2285–2299.

- Langlois DM, Andreae M (October 2011). "Group A streptococcal infections". Pediatrics in Review. 32 (10): 423–9, quiz 430. doi:10.1542/pir.32-10-423. PMID 21965709. S2CID 207170856.

- Marks, James; Miller, Jeffrey (2013). Lookingbill and Marks' Principles and Dermatology, Fifth Edition. Elsevier. pp. 183–195.

- Tanz, Robert (2018). "Sore Throat". Nelson Pediatric Symptom-Based Diagnosis. Elsevier. pp. 1–14.

- McShan, W. Michael (February 1997). "Bacteriophage T12 of Streptococcus pyogenes integrates into the gene encoding a serine tRNA". Molecular Microbiology. 23 (4): 719–728. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2591616.x. PMID 9157243.

- Zabriskie, J. B. (1964). "The role of temperate bacteriophage in the production of erythrogenic toxin by Group A Streptococci". Journal of Experimental Medicine. 119 (5): 761–780. doi:10.1084/jem.119.5.761. PMC 2137738. PMID 14157029.

- Krause, R. M. (2002). "A Half-century of Streptococcal Research: Then & Now". Indian Journal of Medical Research. 115: 215–241. PMID 12440194.

- McShan, W. M.; Ferretti, J. J. (1997). "Genetic diversity in temperate bacteriophages of Streptococcus pyogenes: identification of a second attachment site for phages carrying the erythrogenic toxin A gene". Journal of Bacteriology. 179 (20): 6509–6511. doi:10.1128/jb.179.20.6509-6511.1997. PMC 179571. PMID 9335304.

- Weeks, C. R.; Ferretti, J. J. (1986). "Nucleotide sequence of the type A streptococcal exotoxin (erythrogenic toxin) gene from Streptococcus pyogenes bacteriophage T12". Infection and Immunity. 52 (1): 144–150. doi:10.1128/IAI.52.1.144-150.1986. PMC 262210. PMID 3514452.

- Yu, C. E.; Ferretti, J. J. (1991). "Molecular characterization of new group A streptococcal bacteriophages containing the gene for streptococcal erythrogenic toxin A (speA)". Molecular and General Genetics. 231 (1): 161–168. doi:10.1007/BF00293833. PMID 1753942. S2CID 36197596.

- American Academy of Pediatrics (2013). Baker, Carol (ed.). Red Book Atlas of Pediatric Infectious Diseases. American Academy of Pediatrics. pp. 473–476. ISBN 9781581107951.

- Ferri, Fred (2009). Ferri's Color Atlas and Text of Clinical Medicine. Saunders. pp. 47–48.

- Kato, Hirohisa (2010). Cardiology, Third Edition. Elsevier. pp. 1613–1626.

- Habif, Thomas (2016). Clinical Dermatology. Elsevier. pp. 534–576.

- Adams, James (2013). Emergency Medicine Clinical Essentials. Saunders. pp. 149–158.

- "Initiative for Vaccine Research (IVR)—Group A Streptococcus". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 13 May 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- Chih-Feng, Kuo; Tsao, Nina; I-Chen, Hsieh; Yee-Shin, Lin; Jiunn-Jong, Wu; Yu-Ting, Hung (March 2017). "Immunization with a streptococcal multiple-epitope recombinant protein protects mice against invasive group A streptococcal infection". PLOS ONE. 12 (3): e0174464. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1274464K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0174464. PMC 5371370. PMID 28355251.

- Rudolf Franck - Moderne Therapie in Innerer Medizin und Allgemeinpraxis - Ein Handbuch der Medikamentösen, Physikalischen und Diätetischen Behandlungsweisen der Letzten Jahre. Springer Verlag. 13 August 2013. ISBN 9783662221860. Archived from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

- Ellis, Ronald W.; Brodeur, Bernard R. (2012). New Bacterial Vaccines. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 158. ISBN 9781461500537. Archived from the original on 9 January 2017.

- Ferri, Fred (2018). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2018. Elsevier. p. 1143.

- "Second HK child dies of mutated scarlet fever". Associated Press (online). 22 June 2011. Archived from the original on 24 June 2011. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

- "Managing scarlet fever". BMJ. 362: k3005. 2018. doi:10.1136/bmj.k3005. ISSN 0959-8138. PMID 30166279. S2CID 52136139.

- Guerrant, Richard; Walker, David; Weller, Peter (2011). Tropical Infectious Diseases: Principles, Pathogens and Practice. Elsevier. pp. 203–211. ISBN 9780702039355.

- Basetti, S.; Hodgson, J.; Rawson, T.M.; Majeed, A. (August 2017). "Scarlet Fever: A guide for general practitioners". London Journal of Primary Care. 9 (5): 77–79. doi:10.1080/17571472.2017.1365677. PMC 5649319. PMID 29081840.

- "Scarlet fever in England reaches highest level in 50 years". Pharmaceutical Journal. 30 November 2017. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- Rolleston, J. D. (1928). "The History of Scarlet Fever". BMJ. 2 (3542): 926–929. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.3542.926. PMC 2456687. PMID 20774279.

- Ferretti, Joseph; Kohler, Werner (February 2016). "History of Streptococcal Research". Streptococcus Pyogenes: Basic Biology to Clinical Manifestations. PMID 26866232.

- http://www.nasonline.org/publications/biographical-memoirs/memoir-pdfs/dochez-alphonse.pdf

- Dukes, Clement (30 June 1900). "On the confusion of two different diseases under the name of rubella (rose-rash)". The Lancet. 156 (4011): 89–95. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)65681-7.

- Weisse, Martin E (31 December 2000). "The fourth disease, 1900–2000". The Lancet. 357 (9252): 299–301. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03623-0. PMID 11214144. S2CID 35896288.

- Powell, KR (January 1979). "Filatow-Dukes' disease. Epidermolytic toxin-producing staphylococci as the etiologic agent of the fourth childhood exanthem". American Journal of Diseases of Children. 133 (1): 88–91. doi:10.1001/archpedi.1979.02130010094020. PMID 367152.

- Melish, ME; Glasgow, LA (June 1971). "Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome: the expanded clinical syndrome". The Journal of Pediatrics. 78 (6): 958–67. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(71)80425-0. PMID 4252715.

- Morens, David M; Katz, Alan R; Melish, Marian E (31 May 2001). "The fourth disease, 1900–1881, RIP". The Lancet. 357 (9273): 2059. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)05151-5. PMID 11441870. S2CID 35925579.

- Huber, B. (2006). "100 years of allergy: Clemens von Pirquet—his idea of allergy and its immanent concept of disease" (PDF). Wiener klinische Wochenschrift. 118 (19–20): 573–579. doi:10.1007/s00508-006-0701-3. PMID 17136331. S2CID 46144926.

- Cantacuzène, J.; Bonciu, O. (1926). "Modifications subies par des streptocoques d'origine non scarlatineuse au contact de produits scarlatineux filtrès". Comptes rendus de l'Académie des Sciences (in French). 182: 1185–1187.

- Lamagni, Theresa; Guy, Rebecca; Chand, Meera (2018). "Resurgence of scarlet fever in England, 2014–16: a population-based surveillance study". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. The Lancet: Infectious Disease. 18 (2): 180–187. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30693-X. PMID 29191628.

- Branswell, Helen (27 November 2017). "Scarlet fever, a disease of yore, is making a comeback in parts of the world". STAT.

- Dick, G. F.; Dick, G. H. (1924). "A skin test for susceptibility to scarlet fever". Journal of the American Medical Association. 82 (4): 265–266. doi:10.1001/jama.1924.02650300011003.

- Claude, B; McCartney, J.E.; McGarrity, J. (January 1925). "The Dick test for susceptibility to scarlet fever". The Lancet. 205 (5292): 230–231. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)56009-7.

External links

| Classification |

|

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Scarlet fever. |