STS-61-B

STS-61-B was NASA's 23rd Space Shuttle mission, and its second using Space Shuttle Atlantis. The shuttle was launched from Kennedy Space Center, Florida, on 26 November 1985. During STS-61-B, the shuttle crew deployed three communications satellites, and tested techniques of constructing structures in orbit. Atlantis landed at Edwards Air Force Base, California, at 16:33 EST on 3 December 1985, after 6 days and 21 hours in orbit.

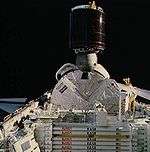

Construction of the ACCESS structure. | |

| Mission type | Satellite deployment Technology |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA |

| COSPAR ID | 1985-109A |

| SATCAT no. | 16273 |

| Mission duration | 6 days, 21 hours, 4 minutes, 49 seconds |

| Distance travelled | 3,970,181 kilometres (2,466,956 mi) |

| Orbits completed | 109 |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft | Space Shuttle Atlantis |

| Launch mass | 118,664 kilograms (261,609 lb) |

| Landing mass | 93,316 kilograms (205,727 lb) |

| Payload mass | 21,791 kilograms (48,041 lb) |

| Crew | |

| Crew size | 7 |

| Members | |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | 27 November 1985, 00:29:00 UTC |

| Launch site | Kennedy LC-39A |

| End of mission | |

| Landing date | 3 December 1985, 21:33:49 UTC |

| Landing site | Edwards Runway 22 |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric |

| Regime | Low Earth |

| Perigee altitude | 361 kilometres (224 mi) |

| Apogee altitude | 370 kilometres (230 mi) |

| Inclination | 28.5 degrees |

| Period | 91.9 min |

Back row L-R: Walker, Ross, Cleave, Spring, Neri Vela Front row L-R: O'Conner, Shaw | |

STS-61-B marked the quickest turnaround of a Shuttle orbiter from launch to launch in history – just 54 days elapsed between Atlantis' launch on STS-51-J and launch on STS-61-B. This record for turn around between two flights of the same orbital space vehicle was only beaten in July 2020 by SpaceX. The mission was also notable for carrying the first Mexican astronaut, Rodolfo Neri Vela. This was also Atlantis' second and final mission to launch before the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster in 1986, which would ground the shuttle fleet for two and a half years; Atlantis would not fly again until STS-27, which launched on December 2, 1988, roughly three years later.

Crew

| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | Second spaceflight | |

| Pilot | First spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 1 | First spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 2 | First spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 3 | Only spaceflight | |

| Payload Specialist 1 | Third and last spaceflight | |

| Payload Specialist 2 | Only spaceflight | |

Backup crew

| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Payload Specialist 1 | First spaceflight | |

| Payload Specialist 2 | First spaceflight | |

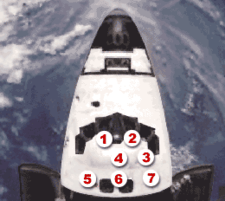

Crew seating arrangements

| Seat[1] | Launch | Landing |  Seats 1–4 are on the Flight Deck. Seats 5–7 are on the Middeck. |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Shaw | Shaw | |

| S2 | O'Connor | O'Connor | |

| S3 | Ross | Spring | |

| S4 | Cleave | Cleave | |

| S5 | Spring | Ross | |

| S6 | Walker | Walker | |

| S7 | Neri Vela | Neri Vela | |

Shuttle processing

After landing at the Edwards Air Force Base at the end of STS-51-J on 7 October 1985, Atlantis returned to the Kennedy Space Center on 12 October. The shuttle was moved directly into an Orbiter Processing Facility (OPF), where post-flight de-servicing and pre-flight processing took place simultaneously.

After only 26 days in the OPF, a record fast processing in the history of the Space Shuttle program, the shuttle was rolled to the Vehicle Assembly Building on 7 November.[2] Atlantis was mated with the External Tank and Solid Rocket Booster stack and was rolled out to launch pad 39A on 12 November 1985.

Payload

Three satellites were deployed during the mission: Aussat 2, Morelos II, and Satcom K2. The first two were the second in their series, the first examples having been deployed during STS-51-I and STS-51-G. Both were Hughes HS-376 satellites equipped with a PAM-D booster to reach geosynchronous transfer orbit. Satcom K2, meanwhile, was a version of the RCA 4000 series. RCA American Communications owned and operated the satellite system of which Satcom K2 was a part. The satellite was deployed using a PAM-D2 booster, a larger version of the PAM-D. This was the first flight of this booster stage on a Space Shuttle.

All three satellites were successfully deployed, one at a time, and their booster stages fired automatically to lift them to geosynchronous transfer orbits. Their respective owners assumed charge, and later fired the onboard kickmotors at apogee, to circularize the orbits and align them with the equator.

Middeck payloads

- Continuous Flow Electrophoresis System (CFES)

- Diffusive Mixing of Organic Solutions (DMOS)

- Morelos Payload Specialist Experiments (MPSE) and Orbiter Experiments (OEX)

Other items

A checkered racing flag was carried onboard Atlantis during STS-61-B; the flag is now on display at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Hall of Fame Museum. This was also the second test flight of the OEX advanced autopilot. It ran for approximately 65 hours and demonstrated the ability to fly the orbiter on nose jets only, aft jets only, to automatically stationkeep on another satellite and to fly an orbit with zero aerodynamic drag. The OEX autopilot was also more fuel efficient than the baseline system.

Mission summary

Space Shuttle Atlantis lifted off from Pad A of Launch Complex 39 at Kennedy Space Center at 19:29 pm EST on 26 November 1985. The launch marked the second night launch of the Space Shuttle program, and the ninth and final flight of 1985.[3]

A key element of the mission's objectives was EASE/ACCESS, an experiment in assembling large structures in space. EASE/ACCESS was a joint venture between the Langley Research Center and the Marshall Space Flight Center. ACCESS was a "high-rise" tower composed of many small struts and nodes. EASE was a geometric structure shaped like an inverted pyramid, composed of a few large beams and nodes. Together, they demonstrated the feasibility of assembling large pre-formed structures in space. Astronauts Jerry Ross and Sherwood Spring performed the two spacewalks of the mission which marked the 50th and 51st U.S. (12th and the 13th for the Shuttle) EVAs. An IMAX camera mounted in the cargo bay filmed the activities of the astronauts engaged in the EASE/ACCESS work, as well as other scenes of interest.

"This is probably not the preferred way of building a space station," Ross said later of EASE.[4][5] The astronauts reported that the most difficult part of the spacewalks was torquing their own masses while holding the EASE beams. The ACCESS worked well, while EASE required too much free floating. The astronauts judged that performing six-hour spacewalks every other day over a five or six-day period was feasible, and recommended glove changes to reduce hand fatigue. Ross said in the Extra-Vehicular Activity (EVA) debrief that the crew had tried to have the Manned Maneuvering Unit (MMU) manifested for use in the second spacewalk, because "for certain applications it would be very useful. In particular if you were building portions of a space station attached to the orbiter, then moving those portions farther than the manipulator arm could transport them." He added that the MMU could be used to attach cable runs and instruments in places out of reach of the shuttle's robotic arm (RMS).

During the mission, astronaut Rodolfo Neri Vela accomplished a series of experiments, primarily related to human physiology. He also photographed Mexico and Mexico City as part of the mission's Earth observations. Astronaut Charles Walker again operated the Continuous Flow Electrophoresis System, the third flight of this larger and improved equipment, to produce commercial pharmaceutical products in microgravity. An experiment in Diffusive Mixing of Organic Solutions, or DMOS, was conducted successfully for 3M. The object of this experiment was to grow single crystals that were larger and more pure than any that could be grown on Earth. One Getaway Special canister stored in Atlantis' payload bay carried a Canadian student experiment, which involved the fabrication of mirrors in microgravity with higher performance than ones made on Earth.

All the experiments on this mission were successfully accomplished, and all equipment operated within established parameters. Atlantis landed safely at Edwards Air Force Base at 16:33 EST on 3 December 1985, after a mission lasting 6 days, 21 hours, and 5 minutes. Atlantis landed one orbit earlier than planned due to lighting concerns at the Edwards AFB. Rollout distance on landing was 10,759 feet lasting 78 seconds.[6]

Deployment of the Morelos II satellite.

Deployment of the Morelos II satellite. STS-61-B crew portrait in-flight on the aft flight deck

STS-61-B crew portrait in-flight on the aft flight deck Atlantis touches down at the lakebed runway at Edwards AFB.

Atlantis touches down at the lakebed runway at Edwards AFB.

Spacewalks

Two spacewalks were conducted during the STS-61-B mission to demonstrate assembly techniques which might be used in space station assembly.[4]

| EVA | Spacewalkers | Start (UTC) | End | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EVA 1 | Jerry Ross Sherwood Spring |

29 November | 29 November | 5 hours 32 minutes |

| EVA 1 focused on human performance during assembling of an experimental erectable truss structure. Ross and Spring first assembled the 3.4-m (11-ft) Assembly Concept for Construction of Erectable Space Structures (ACCESS) assembly jig in Atlantis' payload bay. Each cell was assembled in the jig, then pushed up so that the next cell could be assembled. The astronauts assembled the ACCESS truss in 55 minutes, (EVA time line allotted two hours for a single ACCESS assembly) so they assembled it and built it again. The Experimental Assembly of Structures through EVA (EASE) task involved putting together beams weighing 29 kg (64 lb) to make a 3.6-m (12-ft) three-sided pyramid assessed the capabilities of free-floating astronauts. EASE was scheduled to be assembled six times, but Ross and Spring managed eight assemblies. During the first four assemblies the astronauts used foot restraints. In his post flight debriefing, Spring noted that his fingers grew numb during the third EASE assembly and very tired during the fourth. At the end of the EVA Spring assembled and hand-deployed a small target satellite to be used after the EVA as a station-keeping target for Atlantis, which played the role of an automated orbital maneuvering vehicle in rendezvous software tests. | ||||

| EVA 2 | Jerry Ross Sherwood Spring |

1 December | 1 December | 6 hours 41 minutes |

| The purpose of EVA 2 was to assess the ability of astronauts to handle large structural elements and the ability of the Shuttle's robotic arm (RRM) to support future station assembly. Ross and Spring assembled nine bays of ACCESS, then placed parts for the tenth bay on the RMS. Ross stepped into the Manipulator Foot Restraint (MFR) and astronaut Mary Cleave positioned him within reach of the top of the ACCESS girder, where he assembled the tenth bay. The parts were not tethered. Ross performed a cable run assembly simulation by attaching a tether along the side of the tower while Cleave positioned him. Then Spring released the bottom of the tower so Ross could try to precisely handle the beam from the RMS. He replaced it in the assembly jig where it started, demonstrating astronaut ability to assemble a truss in one place and install it in another. Spring then replaced Ross on the MFR. He changed a beam on the tower to simulate structural repair, then pointed the truss at the Moon to judge his handling ability. The astronauts took down ACCESS, and Spring assembled EASE from the RMS. Before finishing, he joined two beams to simulate handling a thermal control heat pipe. Ross unlatched the EASE pyramid so that Spring could maneuver it. Then he replaced Spring on the MFR to duplicate the EASE activities. | ||||

Wake-up calls

NASA began a tradition of playing music to astronauts during the Gemini program, and first used music to wake up a flight crew during Apollo 15. Each track is specially chosen, often by the astronauts' families, and usually has a special meaning to an individual member of the crew, or is applicable to their daily activities.[7]

| Flight Day | Song | Artist/Composer | Played for |

|---|---|---|---|

| Day 2 | "Air Force Hymn" | Brewster H. Shaw, Jr. | |

| Day 3 | "America the Beautiful" | ||

| Day 4 | "Marine Corps Hymn" | Bryan O'Connor | |

| Day 5 | "Notre Dame Victory March" | Jerry Ross | |

| Day 6 | "Born in the U.S.A." | Bruce Springsteen |

References

![]()

- "STS-61B". Spacefacts. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- Chris Gebhardt (2 July 2011). "OV-104/ATLANTIS: An International Vehicle for a Changing World". NASAspaceflight.com. Retrieved 3 July 2011.

- NASA (November 1985). "SPACE SHUTTLE MISSION STS-61B PRESS KIT" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved 3 July 2011.

- David S. Portree and Robert C. Trevino (October 1997). "Walking to Olympus :An EVA chronology (Monograpahs in Aerospace History Series #7)" (PDF). NASA History Office. Retrieved 3 July 2011.

- "Astronauts Believe Lengthy EVA Building Sessions are Feasible". Aviation Week & Space Technology: 20–21. 16 December 1985.

- NASA. "STS-61B". NASA. Retrieved 3 July 2011.

- Fries, Colin (25 June 2007). "Chronology of Wakeup Calls" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved 13 August 2007.

.jpg)