Long Duration Exposure Facility

NASA's Long Duration Exposure Facility, or LDEF (pronounced "eldef"), was a school bus-sized cylindrical facility designed to provide long-term experimental data on the outer space environment and its effects on space systems, materials, operations and selected spores' survival.[1][2] It was placed in low Earth orbit by Space Shuttle Challenger in April 1984. The original plan called for the LDEF to be retrieved in March 1985, but after a series of delays it was eventually returned to Earth by Columbia in January 1990.[2]

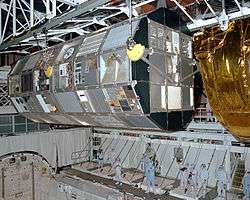

LDEF, shortly before deployment, flies on the RMS arm of Space Shuttle Challenger over Baja California. | |

| Mission type | Materials research |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA |

| COSPAR ID | 1984-034B |

| SATCAT no. | 14898 |

| Website | crgis |

| Mission duration | 2076 days |

| Distance travelled | 1,374,052,506 km (853,796,644 mi) |

| Orbits completed | 32,422 |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Manufacturer | Langley |

| Launch mass | 9,700 kg (21,400 lb) |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | April 6, 1984, 13:58:00 UTC |

| Rocket | Space Shuttle Challenger STS-41-C |

| Launch site | Kennedy LC-39A |

| End of mission | |

| Recovered by | Space Shuttle Columbia STS-32 |

| Recovery date | January 12, 1990, 15:16 UTC |

| Landing date | January 20, 1990, 09:35:37 UTC |

| Landing site | Edwards Runway 22 |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric |

| Regime | Low Earth |

| Eccentricity | 7.29E-4 |

| Perigee altitude | 473.0 km (293.9 mi) |

| Apogee altitude | 483.0 km (300.1 mi) |

| Inclination | 28.5 degrees |

| Period | 94.2 minutes |

It successfully carried science and technology experiments for about 5.7 years that have revealed a broad and detailed collection of space environmental data. LDEF's 69 months in space provided scientific data on the long-term effects of space exposure on materials, components and systems that has benefited NASA spacecraft designers to this day.[3]

History

Researchers identified the potential of the planned Space Shuttle to deliver a payload to space, leave it there for a long-term exposure to the harsh outer space environment, and on a separate mission retrieve the payload and return it to Earth for analysis. The LDEF concept evolved from a spacecraft proposed by NASA's Langley Research Center in 1970 to study the meteoroid environment, the Meteoroid and Exposure Module (MEM).[1] The project was approved in 1974 and LDEF was built at NASA's Langley Research Center.[3]

LDEF was intended to be reused, and redeployed with new experiments, perhaps every 18 months.[4] but after the unintended extension of mission 1 the structure itself was treated as an experiment and intensively studied before being placed into storage.

Launch and deployment

The STS-41-C crew of Challenger deployed LDEF on April 7, 1984, into a nearly circular orbit at an altitude of 275 nautical miles.[5]

Design and structure

The LDEF structure shape was a 12 sided prism (to fit the shuttle orbiter payload bay), and made entirely from stainless steel. There were 5 or 6 experiments on each of the 12 long sides and a few more on the ends. It was designed to fly with one end facing earth and the other away from earth.[6] Attitude control of LDEF was achieved with gravity-gradient stabilization and inertial distribution to maintain three-axis stability in orbit. Therefore, propulsion or other attitude control systems were not required, making LDEF free of acceleration forces and contaminants from jet firings.[3] There was also a magnetic/viscous damper to stop any initial oscillation after deployment.[6]

It had two grapple fixtures. An FRGF and an active (rigidize sensing) grapple used to send an electronic signal to initiate the 19 experiments that had electrical systems.[6] This activated the Experiment Initiate System (EIS)[7]:1538 which sent 24 initiation signals to the 20 active experiments. There were six initiation indications which were visible to the deploying astronauts [8]:109 next to the active grapple fixture.[8]:111

Engineers originally intended that the first mission would last about one year, and that several long-duration exposure missions would use the same frame. The exposure facility was actually used for a single 5.7-year mission.

Experiments

The LDEF facility was designed to glean information vital to the development of the Space Station Freedom (that was eventually built as the International Space Station) and other spacecraft, especially the reactions of various space building materials to radiation, extreme temperature changes and collisions with space matter.

Some of the experiments had a cover that opened after deployment and was designed to close after about a year,[9] e.g., Space Environment Effects (M0006).[10]

There was no telemetry, but some active experiments recorded data on a magnetic tape recorder that was powered by a lithium sulfur dioxide battery,[9] e.g., the Advanced Photovoltaic Experiment (S0014), which recorded data once a day,[11] the German Solar cell study (S1002),[11]:91 and the Space Environment Effects on Fiber Optics Systems (M004).[10]:182

Six of the seven active experiments that needed to record data used one or two Experiment Power and Data System (EPDS) modules.[7]:1545 Each EPDS contained a processing and control module, a magnetic tape recorder and two LiSO2 batteries.[7]:1536 One experiment (S0069) used a 4-track magnetic tape module not as part of an EPDS.[7]:1540

Fifty-seven science and technology experiments — involving government and university investigators from the United States, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom — flew on the LDEF mission.[3] A total of 57 experiments were conducted on the LDEF.[2] Interstellar gases also would be trapped in an attempt to find clues into the formation of the Milky Way and the evolution of heavier elements.[3] Some examples are investigation of exposure effects on:

- materials, coatings, and thermal systems

- power and spacecraft propulsion

- optical fibers and pure crystals for use in electronics

- electronics and optics

- survival of tomato seeds and bacterial spores[3]

and physics in low gravity – e.g. crystal growth.[12]

At least one of the on-board experiments, the Thermal Control Surfaces Experiment (TCSE), used the RCA 1802 microprocessor.[13]

Experiment results

EXOSTACK

In the German experiment EXOSTACK, 30% of Bacillus subtilis spores survived the nearly 6 years exposure to outer space when embedded in salt crystals, whereas 80% survived in the presence of glucose, which stabilize the structure of the cellular macromolecules, especially during vacuum-induced dehydration.[14][15]

If shielded against solar UV, spores of B. subtilis were capable of surviving in space for up to 6 years, especially if embedded in clay or meteorite powder (artificial meteorites). The data may support the likelihood of interplanetary transfer of microorganisms within meteorites, the so-called lithopanspermia hypothesis.[15]

SEEDS

The Space Exposed Experiment Developed for Students (SEEDS) allowed students the opportunity to grow control and experimental tomato seeds that had been exposed on LDEF comparing and reporting the results. 12.5 million seeds were flown, and students from elementary to graduate school returned 8000 reports to NASA. The L.A. Times misreported that a DNA mutation from space exposure could yield a poisonous fruit. While incorrect, the report served to raise awareness of the experiment and generate discussion.[16] Space seeds germinated sooner and grew faster than the control seeds. Space seeds were more porous than terrestrial seeds.[17]

Retrieval

At LDEF's launch, retrieval was scheduled for March 19, 1985, eleven months after deployment.[3] Schedules slipped, postponing the retrieval mission first to 1986, then indefinitely due to the Challenger disaster. After 5.7 years its orbit had decayed to about 175 nautical miles and it was likely to burn up on reentry in a little over a month.[5][8]:15

It was finally recovered by Columbia on mission STS-32 on January 12, 1990.[18] Columbia approached LDEF in such a way as to minimize possible contamination to LDEF from thruster exhaust.[19] While LDEF was still attached to the RMS arm, an extensive 4.5 hour survey photographed each individual experiment tray, as well as larger areas.[19] Nevertheless, shuttle operations did contaminate experiments when concerns for human comfort out-weighed important LDEF mission goals.[20]

Columbia landed at Edwards Air Force Base on January 20, 1990.[3] With LDEF still in its bay, Columbia was ferried back on the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft to the Kennedy Space Center on January 26. Special efforts were taken to ensure protection against contamination of the payload bay during the ferry flight.[3]

Between January 30 and 31, LDEF was removed from Columbia's payload bay in KSC's Orbiter Processing Facility, placed in a special payload canister, and transported to the Operations and Checkout Building. On February 1, 1990, LDEF was transported in the LDEF Assembly and Transportation System to the Spacecraft Assembly and Encapsulation Facility – 2, where the LDEF project team led deintegration activities.[19]

See also

- European Retrievable Carrier, 1992–1993

- Space Flyer Unit, 1995–1996

- Mir Environmental Effects Payload, 1996–1997

- Materials International Space Station Experiment, (1–8) from 2001

References

- "The Long Duration Exposure Facility". NASA. Langley Research Center. Archived from the original on 2013-10-31. Retrieved 2013-07-29.

- Allen, Carlton. "Long Duration Exposure Facility (LDEF)". NASA. Retrieved 2014-01-22.

- Grinter, Kay (8 January 2010). "Retrieval of LDEF provided resolution, better data" (PDF). Spaceport News. NASA. p. 7. Retrieved 2014-01-22.

- LDEF intro

- archive of larc LDEF

- LDEF structure

- LDEF Electronic Systems: Successes, Failures and Lessons, Miller et al. 1991

- ANALYSIS OF SYSTEMS HARDWARE FLOWN ON LDEF – RESULTS OF THE SYSTEMS SPECIAL INVESTIGATION GROUP. April 1992

- LDEF Trays and Experiments

- Electronics and Optics

- Advanced Photovoltaic Experiment (S0014)

- Growth of Crystals From Solutions in Low Gravity (A0139A)

- "Thermal Control Surfaces Experiment (TCSE)" (PDF). NASA Online Archives. NASA. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Paul Clancy (Jun 23, 2005). Looking for Life, Searching the Solar System. Cambridge University Press.

- Horneck, Gerda; David M. Klaus; Rocco L. Mancinelli (March 2010). "Space Microbiology". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 74 (1): 121–156. Bibcode:2010MMBR...74..121H. doi:10.1128/mmbr.00016-09. PMC 2832349. PMID 20197502.

- Sindelar, Terri (April 17, 1992). "Attack of the Killer Space Tomatoes? Not!". Washington, D.C.: NASA.

- Hammond EC, Bridgers K, Berry FD (1996). "Germination, growth rates, and electron microscope analysis of tomato seeds flown on the LDEF". Radiat Meas. 26 (6): 851–61. Bibcode:1996RadM...26..851H. doi:10.1016/S1350-4487(96)00093-5. hdl:2060/19950017401. PMID 11540518.

- "LDEF Archive". Langley Research Center. Archived from the original on October 31, 2013. Retrieved July 16, 2010.

- Kramer, Herbert J. "LDEF (Long Duration Exposure Facility)". NASA. Earth Observation Portal. Retrieved 2014-01-22.

- Zolensky, M. "Lessons Learned from Three Recent Sample Return Missions" (PDF).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Long Duration Exposure Facility. |

- "NASA Langley LDEF Site". Archived from the original on May 29, 2016. Retrieved September 11, 2016.

- NASA Johnson Space Center LDEF site

- LDEF Intercostal Data and Plots re micrometeoroids cratering

- LDEF Map of Experiment Locations

- The Long Duration Exposure Facility (LDEF), Mission 1 Experiments, 1984. NASA SP-473