Harbour Defence Motor Launch

The Harbour Defence Motor Launch (HDML) was a British small motor vessel built during World War II.

ML 1322, a Royal Australian Navy HDML, in Brisbane in 1944 | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Harbour defence motor launch (HDML) |

| Completed: | 486 |

| Active: | Until the early 1970s |

| General characteristics | |

| Displacement: | 54 tons (full load displacement) |

| Length: | 72 ft (22 m) |

| Beam: | 16 ft (4.9 m) |

| Draught: | 5 ft (1.5 m) |

| Installed power: | 152 bhp (113 kW) each engine[1] |

| Propulsion: | Twin handed Gardner 8L3 marine engines[1] |

| Speed: | 12.5 knots (23.2 km/h; 14.4 mph) |

| Range: | 2,000 mi (1,700 nmi; 3,200 km) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph)(1,650 gallons) |

| Complement: | 2 officers, 2 petty officers and 8 ratings |

| Armament: | Typically twin 20mm Oerlikons, twin Vickers K machine guns and six depth charges |

The HDML was designed by W J Holt at the Admiralty in early 1939. During the war, 464 HDMLs were constructed, mainly by yacht builders, in the United Kingdom and a number of other allied countries. In view of their later expanded combat roles in some Commonwealth navies some HDMLs were re-designated as "Seaward Defence Motor Launches" (SDML) or "Seaward Defence Boats" (SDB).[2]

Design and construction

HDMLs had a round bilge heavy displacement hull 72 feet (22 m) long with a beam of 16 feet (4.9 m) and a loaded draught of 5 feet (1.5 m). Loaded displacement was 54 tons. The hull had a pronounced flare forward to throw the bow wave clear and provided considerable lift to prevent all but the heaviest seas from coming aboard. Although seaworthy, the boat had a considerable tendency to roll, especially when taking seas at anything other than directly ahead or astern. The cause was the round bilge midship section and a considerable reserve of stability, the effect of which was to impart a powerful righting moment if the boat was pushed over in a seaway. This, coupled with the round bilged hull and lack of bilge keels, would set up a rapid and violent rolling.

One of the design criteria was that the boat had to be capable of turning inside the turning circle of a submerged submarine. To achieve this, HDMLs were fitted with two very large rudders and, to reduce resistance to turning, the keel ended 13 ft (4.0 m) before the stern. A side effect of this was that the boat lacked directional stability and was extremely difficult to hold on a straight course.

The hull was of round bilge wooden construction, planked with two diagonally opposed skins with a layer of oiled calico between them – known as a "double-diagonal" technique. The hull was completed with frames or "timbers" riveted perpendicularly from the keel to the gunwale on the inside of the planking, forming a very strong hull. The hull was further strengthened by the addition of longitudinal stringers riveted inside the timbers together with further timbers, known as "web frames". They were fastened inside the stringers opposite every third main timber. HDMLs were fitted with a deeper section rubbing strake aft. Its purpose was to roll depth charges (kept in and delivered from racks on the side decks) clear of the hull and propellers.

Most HDML hulls were planked in mahogany, but as the war progressed this became scarce and larch was used, although this tended to lead to leaky hulls. The decks were also of double-diagonal construction and generally made of softwood. Boats operating in tropical waters (including the Mediterranean Sea) were sheathed in copper below the waterline to prevent the attack of marine borers.

In order to lessen the chances of the boat sinking in the event of damage to the hull, they were divided into six watertight compartments. Provided that the bulkheads were not damaged, the boat could remain afloat with any one compartment flooded.

Some were constructed in the United States and nominally owned by the United States Navy, but delivered to the Royal Navy and other allies under Lend-Lease. Most were returned to the United States Navy at the end of the war before being sold to other countries, the majority to the Royal Netherlands Navy.

Accommodation

HDMLs were designed to accommodate a crew of ten. There were berths for six ratings in the fore cabin, which also contained a galley with a coal fired stove.[note 1] In the forepeak, there was a Baby Blake sea toilet and hand wash basin. The officers were berthed in the after end of the boat; the petty officers being in a cabin on the port side just aft of the engine room with their own separate toilet and hand wash basin. A small "Courtier" coal-fired stove provided heating.

The commissioned officers had comparatively roomy accommodation in the wardroom aft, although it suffered from being situated above the propeller shafts and therefore subject to noise and vibration. The wardroom also contained the ship’s safe, a dining table and seating, a wine and spirit locker, a small coal stove and a tiny footbath.

The boat's radio room was a small compartment situated aft on the starboard side, adjacent to the petty officers’ toilet.

The chartroom was located on the main deck. It contained the chart table, a casual berth and a second steering position. On the forward bulkhead a navigational switchboard was fitted, which included a duplicate set of engine revolution indicators, switches for the navigation lights, clear view screens and the "action-stations" alarm.

The main steering position was on the open bridge where the two engine room telegraphs were fitted. There were also voice pipes connected to the inside steering position, the engine room, the radio room and the wardroom.

Engine room

The HDMLs had a manned engine room which usually comprised two engine room staff when in Royal Naval service. There was no direct bridge control of the main engines or machinery. A small ship's telegraph system was used in conjunction with a buzzer system, with predetermined signals for the communication of orders between the engineer and master.

The engineer operated the machinery from a position between the main engine propulsion gearboxes on the centreline of the vessel. This was generally done in the sitting down position, using a removable seat which was hung from the engine room access ladder. Four levers were used to control the two Gardner 8L3s engine's RPM settings and the direction of drive to the propellers via reversing gearboxes. A governor (speed control) control lever was used to adjust the engine revolutions, and a gearbox lever was used with positions for ahead, neutral and reverse.

Settings for the engine governor controls were "slow" 250 RPM, "half" 600 RPM, "full" 800 RPM and "emergency full" 900 RPM, and those settings were possible with the gearboxes in ahead or astern. The vessel's telegraphs indicated the required settings for all levers at any one time.

Other operations included the monitoring of the water jacket temperatures of both prime movers. Gardner design engineers designed the early marine variants of the 8L3s to be direct salt-water–cooled, with an allowance for corrosion included in the water jacket wall thickness. To maintain the correct operating temperature of 62 degrees C, a bypass valve was incorporated in the cooling circuit. This allowed varying amounts of the coolant to be diverted back to the feed side of the pump, thus raising the water temperature before circulating it around the engine. This in turn resulted in a higher overall engine temperature.

A third engine acted as an auxiliary power unit. This was installed within the machinery space and provided motive power for electrical generation and to operate the fire and bilge pump set. This was also a Gardner sourced engine of the type 1L2, and was a single cylinder hand start unit producing 7.5 horsepower (5.6 kW).

Other features of the machinery space were five liquid storage tanks: two large fuel oil tanks on the centre of each wing, with two day service fuel oil tanks just forward of the former, which supplied fuel to all engines by gravity feed. The fifth tank was used to store lubrication oil, and this was generally sited on the port side aft area of the space. The adjacent space on the STB side provided space for the engineer's work bench.

Armament

The intended armament was a QF 3-pounder gun, an Oerlikon 20 mm cannon and two machine guns.[3] As constructed, HDMLs were commonly fitted with a QF 2-pounder gun on the foredeck, an Oerlikon 20 mm high angle/low angle cannon on the stern cabin which could be used against surface targets or anti-aircraft defence and a Vickers K gun or Lewis gun on each side of the bridge. They carried 6 to 8 depth charges on the aft decks. The 2-pounder guns were not particularly accurate, possibly because of the boats' tendency to roll, and many were replaced by another 20 mm Oerlikon HA/LA gun. Some Australian HDMLs also carried Browning .50 calibre machine guns.

Service

HDMLs were originally intended for the defence of estuarial and local waters, but they proved such a seaworthy and versatile design that they were used in every theatre of operations as the war progressed. They were to be found escorting convoys off the West Coast of Africa, carrying out covert activities in the Mediterranean and undertaking anti-submarine patrols off Iceland. They also played major roles in Operations Glimmer and Taxable, deception operations to draw German attention away from the Normandy landings.

In Royal Australian Navy service they were used for coastal patrols around northern Australia, New Guinea and Timor, and for covert activities behind Japanese lines in Southeast Asia.

HDMLs were initially transported as deck cargo on larger ships for foreign service, which is why their length was restricted to 72 feet. Later in the war, with many merchant ships being sunk, it was found to be much safer to move them abroad under their own power. Some HDMLs, undertook fairly substantial ocean voyages. Many belonging to the Mediterranean Fleet sailed from the UK to Malta via Gibraltar in convoy, voyages which necessitated going well out into the Atlantic Ocean in order to keep clear of the enemy occupied coast. Three HDMLs were fitted with a second mast and sails with the intention of sailing to the Caribbean. In the event, they did not make this voyage, joining the Mediterranean fleet instead.

British HDMLs were normally manned by Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (RNVR) officers with temporary commissions, and "hostilities only" ratings. The crews, however, gained an enviable reputation for their skill and expertise in the handling and fighting of their vessels.

Post-war

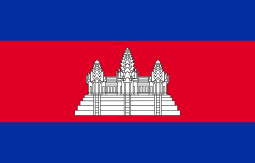

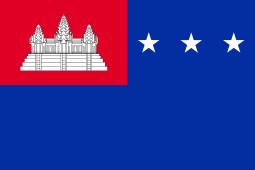

After the war many HDMLs were adapted for other purposes, such as survey vessels, search and rescue, dispatch boats and for fisheries patrols and training. ML1387 (renamed HMS Medusa in 1962), was the last in Royal Naval service, operating as an hydrographic survey vessel until November 1965 and subsequently preserved by the Medusa Trust. The last Royal Australian Navy HDML. HMAS HDML 1321, was paid off in 1971.[4] Others were allocated to naval reserve units. Some were loaned and later sold to countries such as Greece, Cambodia,[5] and the Philippines. Some formerly with British colonial navies, such as the Royal Indian Navy, were transferred on independence to the new countries such as India, Pakistan and Burma. Some were retained by various governments for civilian use, such as police and customs. Those with the Free French Naval Forces during WW2 were incorporated into the French Navy, many based in overseas colonies such as Cameroon and French Indochina. Many were sold out of naval service to become private motor yachts or passenger boats, purposes for which they were ideally suited, with their diesel engines and roomy accommodation. Such was the superior design and build of these craft, that a number still survive today in their civilian role. Others continued in government service before finding their way onto the civilian market at the end of their working lives.

A Royal Hellenic Navy HDML was heavily modified to resemble a German E-boat for use in the 1961 film The Guns of Navarone.

Survivors

The Medusa Trust maintains an extensive archive of documents, photographs and records of nearly all 480 HDMLs and their crews.[6]

HDML ML1387 (renamed HMS Medusa in 1962), is a museum ship in Haslar Marina near Portsmouth and has recently undergone an extensive refit to keep her seagoing.

HDML ML1301 is privately owned.[7] https://mecmuseum.nl/hdml-1301/

HDML 1321 survived as a dive/tour boat. In 2016 a trust was established to purchase and restore 1321 to her wartime configuration, as it is the first Australian-built HDML and took part in the Z Special Operation Copper raid on Muschu Island off Wewak in April 1945. On 19 October 2016, 1321 sank at her mooring in Darwin Harbour - funds are now being raised to salvage the vessel.1321 salvage fund

HDML 1348 Was saved from the scrap heap in 2016 by a private owner. Scott Perry spent 18 months rebuilding her, and has since(as of 2020) done just over 2,500nm in her. Being rebuilt to museum condition is an ongoing exercise, in both labour, time and money. View her on Facebook, under HDML Kuparu.

Builders

This is a partial list of known builders

|

|

|

Users

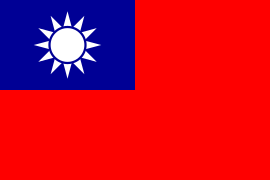

World War II

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

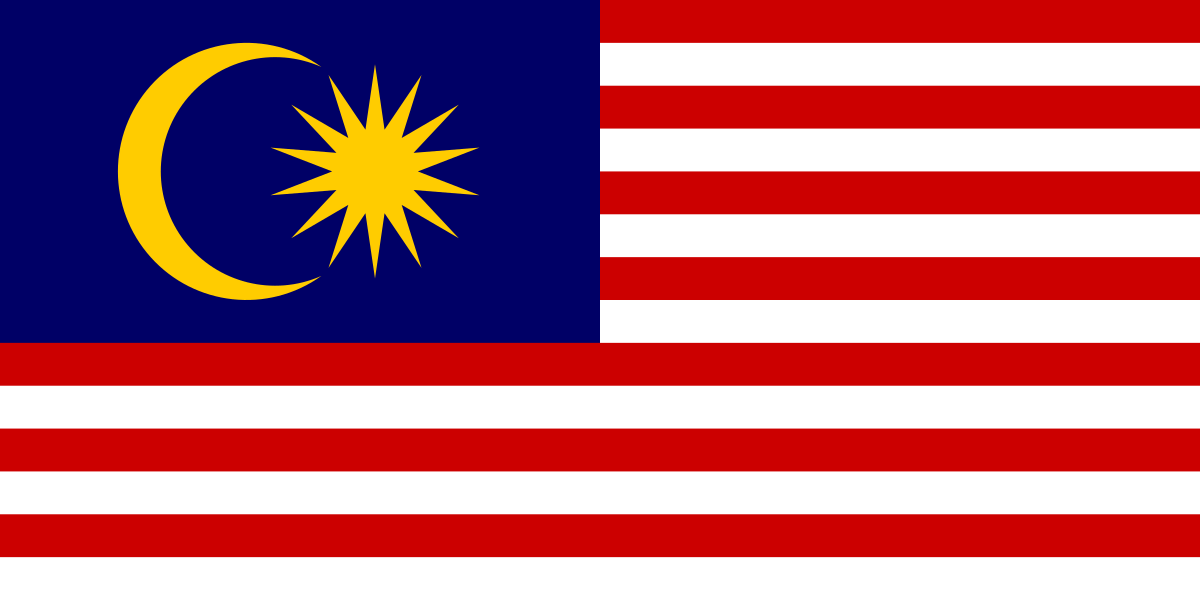

Postwar

- Military

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

- Other government departments

See also

- Harbour Launch

- Motor Launch

- Motor Gun Boat

- Motor Torpedo Boat

- Submarine chaser

- National Historic Ships (many surviving HDMLs in British waters are on its register.)

- British Coastal Forces of World War II

Notes

- Notes

- Admiralty Pattern 3160

- Citations

- General directions for the operation of Gardner L3 Diesel engines, p. 10, The Cloister Press.

- Sea Power Centre history page for SDB 1323, Royal Australian Navy, archived from the original on 21 December 2013

- Chris Bishop (2002). The Encyclopedia of Weapons of World War II. Sterling Publishing Company. p. 525. ISBN 1586637622.

- John Bastock (1975). Australia's Ships of War. Angus and Robertson. p. 176. ISBN 0207129274.

- Conboy, FANK: A History of the Cambodian Armed Forces, 1970-1975 (2011), p. 239.

- Medusa Trust

- "hdmlmeda". Archived from the original on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

References

- Adapted from "Medusa" By Mike Boyce Owner and Master of Medusa HDML1387 for 40 years

- UK National Historic Ships Register

- Allied Coastal Forces Vol.1 by John Lambert and Al Ross

- The Medusa Trust, preserving the small naval vessel of World War II

- Kenneth Conboy, FANK: A History of the Cambodian Armed Forces, 1970-1975, Equinox Publishing (Asia) Pte Ltd, Djakarta 2011. ISBN 9789793780863

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Harbour Defence Motor Launch. |

- The history of The Royal Naval Patrol Service

- HDML 1301 today https://mecmuseum.nl/hdml-1301/

- HDML 1301 ~ Operation Brassard - 17 Jun 1944

- HM HDML 1001 her Royal Navy and subsequent career

- Personal account of life aboard HDML 1383

- Enter HDML or Harbour Defence Motor Launch into search box of BBC's WW2 Peoples' War for more individual accounts.

- HDML 1387 later HMS Medusa at National Historic Ships Register