Rouses Point–Lacolle 223 Border Crossing

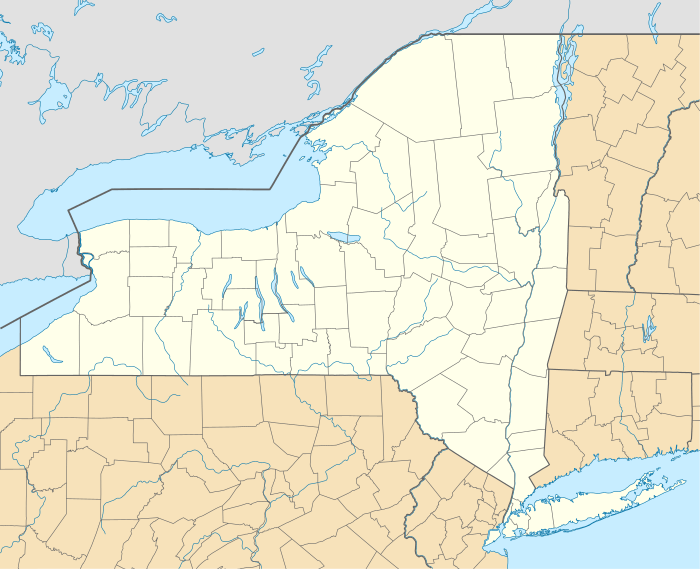

The Rouses Point - Lacolle 223 Border Crossing connects the towns of Lacolle, Quebec and Rouses Point, New York on the Canada–US border. This crossing is open 24 hours per day, 365 days per year. Because the municipality of Lacolle, Quebec has two border crossings, CBSA calls this one 223 to indicate it is the crossing on Quebec Route 223. The other crossing is the Overton Corners–Lacolle 221 Border Crossing immediately to the west. Historically, it was called Cantic, which was a local village name that is no longer used.

| Rouses Point - Lacolle 223 Border Crossing | |

|---|---|

US Border Inspection Station at Rouses Point, NY | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States; Canada |

| Location |

|

| Coordinates | 45.010235°N 73.370819°W |

| Details | |

| Opened | 1913 |

| US Phone | (518) 297-2441 |

| Canadian Phone | (450) 246-3510 |

| Hours | Open 24 hours |

| Website https://www.cbp.gov/contact/ports/champlain | |

U.S. Inspection Station—Rouses Point (St. John's Highway), New York | |

| |

| Location | NY 9B, Rouses Point, New York |

| Built | 1931 |

| Architect | Simon, Louis A.; Wetmore, James A. |

| Architectural style | Georgian Revival |

| MPS | U.S. Border Inspection Stations MPS |

| NRHP reference No. | 14000574[1] |

| Added to NRHP | September 10, 2014 |

During the era of Prohibition in the United States, this was a very popular border crossing. U.S. Route 11, which connects this crossing, was among only a few paved roads at that time, and the US Customs office was not located at the border as it is today. Travelers were expected to drive into the village of Rouses Point to report for inspection and make declarations. Those involved in smuggling rarely would report, so the United States Customs Service moved to construct a border station. By the time construction was completed on the border station (which is still in use today), prohibition had been repealed.[2]

In 2014 the U.S. border inspection station was part of a group in several states along both borders added to the National Register of Historic Places.[1]

Lacolle 223 Border Station

Canada has had a border inspection station at this crossing even before the US built its facility in 1936. In 1932, Canada built a Tudor-revival border station which stood until it was replaced with a brick building in 1971.[3] The original garage still stands at the north end of the CBSA property. A similar Tudor-revival border station still stands at the Trout River Border Crossing.

Rouses Point Border Station

Architectural Description

The US Border Inspection Station at Rouses Point occupies an 81-acre site on the west side of St. John's Highway, New York Route 9B, at the Canada–US border. Facing east, the building is set in an area of open fields with a few light industrial buildings to the east. The site is level around the building, but slopes away gradually on the west.[4]

The Border station has a five-part plan with a two-story central block which faces east, and two single-story wings on the north and south. Unique among the stations, this one also has symmetrical, perpendicular, single-story wings on the west facade for a U-shaped overall plan. There is a three-lane canopy extending from the central block on the east, and cars coming across the border from Canada are directed into the inspection lanes via an oval, asphalt-covered drive. Parking spaces are provided on the south end of the drive. As with most of the other stations, there are symmetrically placed spruce trees over thirty years old at each side of the building, with hedges filling in for a border effect. The landscaping was part of Lady Bird Johnson's beautification program.[4]

The red brick central block is two stories in height beneath a slate-covered, truncated hipped roof. Decorative quoins mark the building's corners, and Vermont marble makes a belt course between floors. A row of modillion blocks is at the cornice. There are marble window sills and keystones over the door and window openings. The main block is seven bays wide, and at each of the outermost bays on the first story is a shallow projecting bay with a copper roof. Sash is 12/12 on the first story, 8/8 on the second story, and is original throughout the building. The main entry has a replacement glass-and-aluminum double-leaf door and transom.[4]

The south wing of the building is divided into four arched vehicle bays on the east and has two bays of 12/12 sash on its west facade. The north wing is five bays wide with 12/12 sash and one bay altered for a pedestrian entry. Quoins are repeated at the wing corners. Each wing is a single bay in width beneath slate-covered hip roofs. Perpendicular to the south wing and extending to the west is a single-story garage ell, eight arched vehicle bays long. Each arch is ornamented with a marble keystone, and four of the openings have the wooden overhead doors which were original to the building. Three have been filled in and a fourth has an aluminum roll-up door. On the north end of the building is a corresponding ell five bays long and five bays wide. Both ells have flat roofs.[4]

The unaltered, three-lane canopy has a flat, copper-covered roof bordered by a wrought iron railing and is supported on wood-paneled piers.[4]

On the interior a central hallway leads to a set of stairs connecting the basement to the second floor. The hallway divides the first floor into a series of offices at each side: Immigration on the south and Customs on the north. A main office at each side of the building has a long paneled counter which divides the room into public and office areas. Customs has its original glass and wood partitions, and both have their original red tile floors, and plaster wall finishes, but the ceilings have been lowered on both first and second floors, and fluorescent ceiling-hung fixtures replace original lighting fixtures. Architrave door surrounds and many of the wood and glass paneled doors remain from the time of construction. On the Customs or north side on the first floor, a Prisoner's Search room with a vault is now in use as a cashier's room with cashier's window. USDA and Customs JURU offices occupy the west wing.[4]

Drug agents occupy offices on the second floor along a double loaded corridor.[4]

Mechanical spaces are located in the basement together with public toilets, which have their original stall partitions. Ceilings are full height and there are new red floor tiles. A backup generator was added in the 1970s.[4]

Space Inventory

| Square Footage | Building Dimensions | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Floor Area Total: | 16231 | Stories/Levels: | 2 |

| First Floor Area: | 8197 | Perimeter: | 694(Linear Ft.) |

| Occupiable Area: | 0 | Depth: | 0(Linear Ft.) |

| Height: | 29(Linear Ft.) | ||

| Length: | 0(Linear Ft.) |

Construction History

| Start Year | End Year | Description | Architect |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1931 | 0 | Original Construction | |

| 1939 | 0 | Roof Replacement | Federal Works Agency |

| 1942 | 0 | New Shower Bath | Federal Works Agency |

| 1945 | 0 | Misc. Repairs & Alterations | Federal Works Agency |

| 1962 | 0 | Electrical Modernization | GSA |

| 1978 | 0 | Repair Window Wells | GSA |

Significance

The US Border Inspection Station in Rouses Point, New York is the easternmost in the state.[5] It is one of seven existing border inspection stations built between 1931 and 1934 along the New York and Canada–US border. It is also one of two stations in Rouses Point. Georgian Revival in style, the building was designed by the Office of the Supervising Architect under James A. Wetmore, during tenure of the Secretary of the Treasury, William H. Woodin, and constructed in 1931. By the time of its completion, Louis A. Simon had become Supervising Architect. Border stations were constructed by the US government at both the Canadian and Mexican border during the 1930s and several common plans and elevations can be discerned among the remaining nineteen stations. The Rouses Point facility shares with the others a residential scale, a Neo-colonial style, and an organization to accommodate functions of both customs and immigration services.[4]

Border stations are associated with four important events in United States history: the imposition of Prohibition between 1919 and 1933; enactment of the Elliott-Fernald public buildings act in 1926 which was followed closely by the Depression; and the popularity of the automobile whose price was increasingly affordable thanks to Henry Ford's creation of the industrial assembly line. The stations were constructed as part of the government's program to improve its public buildings and to control casual smuggling of alcohol which most often took place in cars crossing the border. Their construction was also seen as a means of giving work to the many locally unemployed.[4]

The Rouses Point-St. Johns border station is the most elaborate of the New York stations and is among the best preserved. While the buildings have all sustained systematic alterations, they have retained, in varying degrees, most of their original fabric. This station is on both exterior and interior a fine example of the building type, its character-defining features well-maintained and intact.[4]

History

The era of Prohibition begun in 1919 with the Volstead Act and extended nationwide by the ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution in 1920, resulted in massive bootlegging along the Canada–US border. In New York, early efforts to control bootlegging were carried out by a small number of Customs officers and border patrol officers who were often on foot and horseback. In many cases, New York Custom Houses were a mile or so south of the border and travelers were expected to stop in and report their purchases. The opportunity to remedy this situation and support enforcement of the Prohibition laws was offered by enactment of the Elliott-Fernald public buildings act of 1926 which authorized the government through the Treasury Department to accelerate its building program and began its allocation with $150,000,000 which it later increased considerably.[4]

Rouses Point was the single most important town in New York at the Canada–US border during Prohibition. Bootlegging alcohol along St. John's Highway from Rouses Point to Plattsburgh was so active that the road came to be known as the Rum Trail and ran right in front of the old Custom House in the town center over a mile away from the border. The old station was the hub for custom inspectors and border patrol agents who foiled many attempts at bringing liquor across the border, but missed many more. Control of Rouses Point was understood to be critical, so it received two border inspection stations; one here and a second at Overtons Corner where the only paved road from Canada passed. By the time Prohibition was repealed, the Rouses Point-St. Johns border inspection station had just been completed. However, the end of Prohibition did not mean the end of smuggling, as the public had developed a taste for Canadian liquor and its bootleggers had discovered the money that could be made smuggling raw alcohol into Canada where prices for it were considerably higher.[4]

While the seven New York border inspection stations had been designated for construction as early as 1929, land acquisition and the designing and bidding process was stalled at various stages for each of the buildings and their construction took place unevenly over a period of five years. Rouses Point-St. Johns was the second to the last to have been constructed. The station is still in active use.[4]

Statement of Eligibility for the National Register of Historic Places

The Rouses Point Border Inspection Station on St. John's Highway is one of seven border Stations in New York which are eligible for the National Register according to Criteria A, B and C. The stations have national, state and local significance.[4]

The station is associated with three events which converged to make a significant contribution to the broad patterns of our history: Prohibition, the Public Buildings Act of 1926 and the mass-production of automobiles. Although this border station was not completed until the repeal of Prohibition, it was planned and built as a response to the widespread bootlegging which took place along the border with Canada and continued to serve as important role after 1933 when smuggling continued in both directions across the border.[4]

Conceived in a period of relative prosperity, the Public Buildings Act came to have greater importance to the country during the Depression and funding was accelerated to bring stimulus to state and local economies by putting to work many of the unemployed in building and then manning the stations. Local accounts make clear the number of jobs the station created. Local labor was used to build the station and Rouses Point residents were appointed customs inspectors. The fact that they were arresting neighbors, if not family members, only occasionally affected the zeal with which the inspectors carried out their duties. Once provided with an adequate number of automobiles to meet their adversaries on equal footing, their enforcement success improved.[4]

Rouses Point Border Inspection Station is associated with the life of Louis A. Simon, FAIA, who as Superintendent of the Architect's Office and then as Supervising Architect of the Procurement Division of the United State Treasury Department was responsible for the design of hundreds of government buildings between 1905 and 1939. During his long tenure with the government, Simon, trained in architecture at MIT, was instrumental in the image of the government projected by its public buildings, an image derived from classical western architecture, filtered perhaps through the English Georgian style or given a regional gloss, but one which continues to operate in the collective public vision of government. Simon was unwavering in his defense of what he considered a "conservative-progressive" approach to design in which he saw "art, beauty, symmetry, harmony and rhythm".[6] The debate which his approach stirred in the architectural profession may still be observed in the fact that he is often omitted in architectural reference works.[4]

The border inspection stations do not individually possess high artistic values, but they do represent a distinguishable entity, that of United States Border Stations, whose components are nonetheless of artistic value. This station at Rouses Point is a fine example, and the most elaborate of the border stations, of the Georgian Revival style. Its construction is of the highest quality materials and workmanship. It has integrity of setting and feeling associated with its function, and has retained the integrity of its materials.[4]

There is no evidence that the site has yielded or may be likely to yield information important in prehistory or history.[4]

See also

References

- "National Register of Historic Places Listings". Weekly List of Actions Taken on Properties: 9/08/14 through 9/12/14. National Park Service. 2014-09-19.

- Everest, Allan S. (1978). Rum Across the Border - The Prohibition Era in Northern New York. Syracuse University Press

- "Lacolle 223 Border Crossing". Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- "U.S. Border Station, Rouses Point, NY". General Services Administration. Retrieved 2015-11-01.

- "Chapter 2: The 45th Parallel". United Divide: A Linear Portrait of the USA/Canada Border. The Center for Land Use Interpretation. Winter 2015.

- American Architect and Architecture, August, 1937, vol. 151, p. 51

Attribution