Calyptocephalella

Calyptocephalella is a genus of frogs in the family Calyptocephalellidae. It is represented by a single living species, Calyptocephalella gayi, commonly known as the helmeted water toad, Chilean helmeted bull frog or wide-mouth toad. Additionally, there are a few extinct species that only are known from Late Cretaceous and Paleogene fossil remains from Patagonia in South America and in the Antarctic Peninsula (at times when it was warmer and wetter).[2][3] The helmeted water toad living today is aquatic to semi-aquatic, and found in deep ponds and reservoirs in central Chile and possibly adjacent west-central Argentina.[1][4]

| Calyptocephalella | |

|---|---|

| |

| Calyptocephalella gayi | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Anura |

| Family: | Calyptocephalellidae |

| Genus: | Calyptocephalella Strand, 1928 |

| Species: | C. gayi |

| Binomial name | |

| Calyptocephalella gayi | |

| |

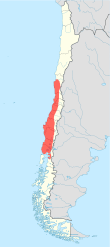

| Range in red | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

This very large toad typically weighs up to 0.5–1 kg (1.1–2.2 lb), but sometimes considerably more. It is threatened by capture for human consumption, habitat loss, pollution, introduced species and the disease chytridiomycosis. It is often kept in herpetoculture; mostly locally where farmed for food, but also in other countries as a pet.[1]

Characteristics

The helmeted water toad is a robust species with a broad head and large mouth.[5] It is very large, and can reach a snout–to–vent length of up to 15.5 cm (6 in) in males and 32 cm (13 in) in females.[4][6] The typical maximum weight is 0.5–1 kg (1.1–2.2 lb),[7][8] but exceptionally large individuals can reach 3 kg (6.6 lb).[1] Such giants are essentially unheard of today, although there are recent records of several individuals weighing 1.2–1.3 kg (2.6–2.9 lb).[9][10] It is the largest anuran (frogs and toads) of the Americas, surpassing other large species like the Blomberg's, cane, Colorado River, cururu and smooth-sided toads, and the American bull-, Lake Junin, mountain chicken and Titicaca water frogs.[5] The maximum snout–to–vent is similar to that of the world's largest frog, the African goliath frog (Conraua goliath), which however can weigh more.[11] Helmeted water toads are colored yellow, brown and green, with light green in mature specimens, while the oldest are gray, or have gray patches on a dark background. The olive-brown to dusky tadpoles also grow unusually large, typically exceeding lengths of 10 cm (4 in) and reaching up to 15 cm (6 in).[4][8]

Behavior

Reproduction and aggressive behavior

The helmeted water toad breeds in the South Hemisphere spring (September–October) when males call.[5] The female lays between 1,000 and 16,000 eggs in shallow, well-vegetated water.[5][6] Although many eggs never hatch, captive studies have shown that a single spawning may result in more than 1,000 tadpoles.[6] Typical larval (tadpole) life lasts five months to a year, but up to two years.[5][8] After hatching, larval survival depends on the presence of vegetation as the existence of movements in the body of water maintain good oxygenation, but the presence of seasonal ponds with some degree of drainage is essential for hatching, as these sites contain fewer predators to the larvae. Then, the transport of larvae from ponds, to larger bodies of water during the rains, or transport of these among several bodies of water facilitates the survival and allows a good development of populations. The larvae prefer cooler areas of the body of water and protective aquatic vegetation, unlike toad larvae that occupy the same sites and have a higher degree of pigmentation that protects them from the solar rays. While the species is almost entirely aquatic, especially young helmeted water toads that are recently metamorphosed from the tadpole stage often can be seen on land.[12] In captivity, they can breed when 2 years old and a female was able to breed until 24 years old.[1]

The helmeted water toad is quite aggressive and it has an aggressive call specifically directed at other individuals of the same species. During encounters with conspecifics they inflate their body, open their large mouth and may jump forward towards an opponent. The same behavior can be directed at potential predators, including humans, although they may choose to escape silently by diving into the water.[12]

Conservation status

The helmeted water toad is a vulnerable species according to IUCN due to capture for human consumption (to a lesser degree also to supply the pet trade), habitat loss, pollution, introduced species (especially trout and African clawed frog) and the disease chytridiomycosis (caused by Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis).[1] The species is kept in frog farms that supply the food market, but helmeted waters toads take three years to reach a marketable size; they have been unable to produce enough to meet the demand and the farms have not been lucrative.[1][13] Despite being illegal in Chile, wild caught individuals are still frequently sold for food in the country and control is insufficient.[13] International trade require a permit, as the species is listed on CITES Appendix III.[14]

On average, helmeted water toads experience water temperatures of about 10 °C (50 °F) in the winter and 20 °C (68 °F) in the summer.[15] While their tolerance is broader,[15] they already have an increased mortality rate at 25 °C (77 °F) and are entirely unable to cope with temperatures of c. 30 °C (86 °F) or warmer.[6][16] It is projected that a significant percentage of the population will disappear before the year 2100 due to global warming.[16] In some places where water levels have been greatly reduced due to a combination of climate change (drought) and extraction for agriculture, mass deaths of helmeted water toads have already been recorded.[6][9]

It is also threatened by the introduction of the African clawed frog (known in Chile as the African toad), a species that has affected, as in other parts of the world, local amphibians when carrying the chytrid fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, which passes through the skin of amphibians not adapted to it. Their cells react to the pathogen, causing hardening and, therefore, hyperkeratosis and death by asphyxiation. The fungus has been classified as a major factor in the decline in amphibian populations worldwide, but in Chile has been reported recently, in 2009. Other causes cited are competition that occurs between African clawed frog and helmeted water toad, introduced for sale in the market for frog legs.

References

- IUCN SSC Amphibian Specialist Group (2019). "Calyptocephalella gayi". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2019: e.T57334A11623098. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-1.RLTS.T4055A85633603.en.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Gómez, R.O.; A.M. Báez; P. Muzzopappa (2011). "A new helmeted frog (Anura: Calyptocephalellidae) from Eocene subtropical lake in northwestern Patagonia, Argentina". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 31 (1): 50–59.

- Mörs, T.; M. Reguero; D. Vasilyan (2020). "First fossil frog from Antarctica: implications for Eocene high latitude climate conditions and Gondwanan cosmopolitanism of Australobatrachia". Scientific Reports. 10: 5051. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-61973-5.

- AmphibiaWeb: Calyptocephalella gayi. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- Halliday, T. (2016). The Book of Frogs: A Life-Size Guide to Six Hundred Species from around the World. University Of Chicago Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-0226184654.

- Acuña-O., P.L.; C.Ma. Vélez-R.; C.E. Mizobe; C. Bustos-López; M. Contreras-López (2014). "Mortalidad de la poblacíon de rana grande chilena, Calyptocephalella gayi (Calyptocephalellidae), en la laguna Matanzas, del Humedal El Yali, en Chile Central". Anales Museo de Historia Natural de Valparaíso. 27: 35–50.

- Toledo; Suazo; and Viana (2014). Formulated diets for giant Chilean frog Calyptocephalella gayi tadpoles. Cien. Inv. Agr. 41(1): 13-20.

- Castañeda, L.E.; P. Sabat; S.P. Gonzalez; R.F. Nespolo (2006). "Digestive Plasticity in Tadpoles of the Chilean Giant Frog (Caudiverbera caudiverbera): Factorial Effects of Diet and Temperature" (PDF). Physiological and Biochemical Zoology: Ecological and Evolutionary Approaches. 79 (5): 919–926. doi:10.1086/506006.

- Mizobe, C.E.; M. Contreras-López; P.L. Acuña-O.; C.Ma. Vélez-R.; C. Bustos-López (2014). "Mortalidad masiva de la rana grande chilena (Calyptocephalella gayi) en la Reserva Nacional El Yali". Biodiversidata. 2: 30–34.

- "Rana Gigante aparece en Leyda en San Antonio". radiofestival.cl. 28 December 2015. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- Sabater-Pi, J. (1985). "Contribution to the biology of the Giant Frog (Conraua goliath, Boulenger)". Amphibia-Reptilia. 6 (1): 143–153. doi:10.1163/156853885x00047.

- Veloso M., A. (1977). "Aggressive Behavior and the Generic Relationships of Caudiverbera caudiverbera (Amphibia:Leptodactylidae)". Herpetologica. 33 (4): 434–442.

- "Expertos advierten que rana chilena está en peligro de desaparecer". Chile Desarrollo Sustentable. 5 August 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- "Calyptocephalella gayi". CITES. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- Cortes, P.A.; H. Puschel; P. Acuña; J.L. Bartheld; F. Bozinovic (2016). "Thermal ecological physiology of native and invasive frog species: do invaders perform better?". Conserv Physiol. 4 (1): cow056. doi:10.1093/conphys/cow056.

- Vidal, M.A.; F. Novoa-Muñoz; E. Werner; C. Torres; R. Nova (2017). "Modeling warming predicts a physiological threshold for the extinction of the living fossil frog Calyptocephalella gayi". J Therm Biol. 69: 110–117. doi:10.1016/j.jtherbio.2017.07.001.

- Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project: Workshop in Chile targets the protection of the Helmeted Water Toad

- Vidal and Labra (2008). Herpetología de Chile. ISBN 978-956-319-420-3