Resonance Raman spectroscopy

Resonance Raman spectroscopy (RR spectroscopy) is a Raman spectroscopy technique in which the incident photon energy is close in energy to an electronic transition of a compound or material under examination.[1] The frequency coincidence (or resonance) can lead to greatly enhanced intensity of the Raman scattering, which facilitates the study of chemical compounds present at low concentrations.[2]

Raman scattering is usually extremely weak, of the order of 1 in 10 million photons that hit a sample are scattered with the loss (Stokes) or gain (anti-Stokes) of energy because of changes in vibrational energy of the molecules in the sample. Resonance enhancement of Raman scattering requires that the wavelength of the laser used is close to that of an electronic transition. In larger molecules the change in electron density can be largely confined to one part of the molecule, a chromophore, and in these cases the Raman bands that are enhanced are primarily from those parts of the molecule in which the electronic transition leads to a change in bond length or force constant in the excited state of the chromophore. For large molecules such as proteins, this selectivity helps to identify the observed bands as originating from vibrational modes of specific parts of the molecule or protein, such as the heme unit within myoglobin.[3]

Overview

Raman spectroscopy and RR spectroscopy provide information about the vibrations of molecules, and can also be used for identifying unknown substances. RR spectroscopy has found wide application to the analysis of bioinorganic molecules. The technique measures the energy required to change the vibrational state of a molecule as does infrared (IR) spectroscopy. The mechanism and selection rules are different in each technique, however, band positions are identical and therefore the two methods provide complementary information.

Infrared spectroscopy involves measuring the direct absorption of photons with the appropriate energy to excite molecular bond vibrational modes and phonons. The wavelengths of these photons lie in the infrared region of the spectrum, hence the name of the technique. Raman spectroscopy measures the excitation of bond vibrations by an inelastic scattering process, in which the incident photons are more energetic (usually in the visible, ultraviolet or even X-ray region) and lose (or gain in the case of anti-Stokes Raman scattering) only part of their energy to the sample. The two methods are complementary because some vibrational transitions that are observed in IR spectroscopy are not observed in Raman spectroscopy, and vice versa. RR spectroscopy is an extension of conventional Raman spectroscopy that can provide increased sensitivity to specific (colored) compounds that are present at low (micro to millimolar) in an otherwise complex mixture of compounds.

An advantage of resonance Raman spectroscopy over (normal) Raman spectroscopy is that the intensity of bands can be increased by several orders of magnitude. An application that illustrates this advantage is the study of the dioxygen unit in cytochrome c oxidase. Identification of the band associated with the O–O stretching vibration was confirmed by using 18O–16O and 16O–16O isotopologues.[4]

Basic theory

The frequencies of molecular vibrations range from less than 1012 to approximately 1014 Hz. These frequencies correspond to radiation in the infrared (IR) region of the electromagnetic spectrum. At any given instant, each molecule in a sample has a certain amount of vibrational energy. However, the amount of vibrational energy that a molecule has continually changes due to collisions and other interactions with other molecules in the sample.

At room temperature, most molecules are in the lowest energy state—known as the ground state. A few molecules are in higher energy states—known as excited states. The fraction of molecules occupying a given vibrational mode at a given temperature can be calculated using the Boltzmann distribution. Performing such a calculation shows that, for relatively low temperatures (such as those used for most routine spectroscopy), most of the molecules occupy the ground vibrational state (except in the case of low-frequency modes). Such a molecule can be excited to a higher vibrational mode through the direct absorption of a photon of the appropriate energy. This is the mechanism by which IR spectroscopy operates: infrared radiation is passed through the sample, and the intensity of the transmitted light is compared with that of the incident light. A reduction in intensity at a given wavelength of light indicates the absorption of energy by a vibrational transition. The energy, , of a photon is

where is Planck's constant and is the frequency of the radiation. Thus, the energy required for such transition may be calculated if the frequency of the incident radiation is known.

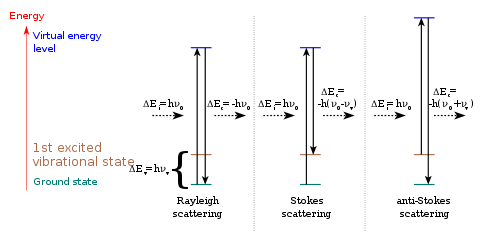

It is also possible to observe molecular vibrations by an inelastic scattering process, Stokes Raman scattering being one such process. A photon is absorbed and then re-emitted (scattered) with lower energy. The difference in energy between the absorbed and re-emitted photons corresponds to the energy required to excite a molecule to a higher vibrational mode. Anti-Stokes Raman scattering is another inelastic scattering process and only occurs from molecules starting in excited vibrational states; it results in light scattered with higher energy. Light scattered elastically (no change in energy between the incoming photons and the re-emitted/scattered photons) is known as Rayleigh scattering.

Generally, the difference in energy is recorded as the difference in wavenumber () between the laser light and the scattered light which is known as the Raman shift. A Raman spectrum is generated by plotting the intensity of the scattered light versus .

Like infrared spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy can be used to identify chemical compounds because the values of are indicative of different chemical species (their so-called chemical fingerprint). This is because the frequencies of vibrational transitions depend on the atomic masses and the bond strengths. Thus, armed with a database of spectra from known compounds, one can unambiguously identify many different known chemical compounds based on a Raman spectrum. The number of vibrational modes scales with the number of atoms in a molecule, which means that the Raman spectra from large molecules is complicated. For example, proteins typically contain thousands of atoms and therefore have thousands of vibrational modes. If these modes have similar energies (), then the spectrum may be incredibly cluttered and complicated.

Not all vibrational transitions are Raman active, meaning that some vibrational transitions do not appear in the Raman spectrum. This is because of the spectroscopic selection rules for Raman spectra. In contrast to IR spectroscopy, where a transition can only be seen when that particular vibration causes a net change in dipole moment of the molecule, in Raman spectroscopy only transitions where the polarizability of the molecule changes along the vibrational coordinate can be observed. This is the fundamental difference in how IR and Raman spectroscopy access the vibrational transitions. In Raman spectroscopy, the incoming photon causes a momentary distortion of the electron distribution around a bond in a molecule, followed by re-emission of the radiation as the bond returns to its normal state. This causes temporary polarization of the bond and an induced dipole that disappears upon relaxation. In a molecule with a center of symmetry, a change in dipole is accomplished by loss of the center of symmetry, while a change in polarizability is compatible with preservation of the center of symmetry. Thus, in a centrosymmetric molecule, asymmetrical stretching and bending are IR active and Raman inactive, while symmetrical stretching and bending is Raman active and IR inactive. Hence, in a centrosymmetric molecule, IR and Raman spectroscopy are mutually exclusive. For molecules without a center of symmetry, each vibrational mode may be IR active, Raman active, both, or neither. Symmetrical stretches and bends, however, tend to be Raman active.

Theory of resonance Raman scattering

In resonance Raman spectroscopy, the wavelength of the incoming photons coincides with an electronic transition of the molecule or material. Electronic excitation of a molecule results in structural changes which are reflected in the enhancement of Raman scattering of certain vibrational modes. Vibrational modes that undergo a change in bond length and/or force constant during the electronic excitation can show a large increase in polarizability and hence Raman intensity. This is known as Tsuboi's rule, which gives a qualitative relationship between the nature of an electronic transition and the enhancement pattern in resonance Raman spectroscopy.[5] The enhancement factor can be by a factor of 10 to > 100,000 and is most apparent in the case of π-π* transitions and least for metal centered (d–d) transitions.[6]

There two primary methods used to quantitatively understand resonance Raman enhancement. These are the transform theory, developed by Albrecht and the time-dependent theory developed by Heller.[7]

Applications

The selective enhancement of the Raman scattering from specific modes under resonance conditions means that resonance Raman spectroscopy is especially useful for large biomolecules with chromophores embedded in their structure. In such chromophores, the resonance scattering from charge-transfer (CT) electronic transitions of the metal complex generally result in enhancement of metal-ligand stretching modes, as well as some of the modes associated with the ligands alone. Hence, in a biomolecule such as hemoglobin, tuning the laser to near the charge-transfer electronic transition of the iron center results in a spectrum reflecting only the stretching and bending modes associated with the tetrapyrrole-iron group. Consequently, in a molecule with thousands of vibrational modes, RR spectroscopy allows us to look at relatively few vibrational modes at a time. The Raman spectrum of a protein containing perhaps hundreds of peptide bonds but only a single porphyrin molecule may show only the vibrations associated with the porphyrin. This reduces the complexity of the spectrum and allows for easier identification of an unknown protein. Also, if a protein has more than one chromophore, different chromophores can be studied individually if their CT bands differ in energy. In addition to identifying compounds, RR spectroscopy can also supply structural identification about chromophores in some cases.

The main advantage of RR spectroscopy over non-resonant Raman spectroscopy is the large increase in intensity of the bands in question (by as much as a factor of 106). This allows RR spectra to be obtained with sample concentrations as low as 10−8 M. It also makes it possible to record Raman spectra of short-lived excited state species when pulsed lasers are used.[8] This is in stark contrast to non-resonant Raman spectra, which usually requires concentrations greater than 0.01 M. RR spectra usually exhibit fewer bands than the non resonant Raman spectrum of a compound, and the enhancement seen for each band can vary depending on the electronic transitions with which the laser is resonant. Since typically, RR spectroscopy are obtained with lasers at visible and near-UV wavelengths, spectra are more likely to be affected by fluorescence. Furthermore, photodegradation (photobleaching) and heating of the sample can occur as the sample also absorbs the excitation light, dissipating the energy as heat.

Instrumentation

The instrumentation used for resonance Raman spectroscopy is identical to that used for Raman spectroscopy; specifically, a highly monochromatic light source (a laser), with an emission wavelength in either the near-infrared, visible, or near-ultraviolet region of the spectrum. Since the energy of electronic transitions (i.e. the color) varies widely from compound to compound, wavelength-tunable lasers, which appeared in the early 1970s, are useful as they can be tuned to coincide with an electronic transition (resonance). However, the broadness of electronic transitions means that many laser wavelengths may be necessary and multi-line lasers (Argon and Krypton ion) are commonly used. The essential point is that the wavelength of the laser emission is coincident with an electronic absorption band of the compound of interest. The spectra obtained contain non-resonant Raman scattering of the matrix (e.g., solvent) also.

Sample handling in Raman spectroscopy offers considerable advantages over FTIR spectroscopy in that glass can be used for windows, lenses, and other optical components. A further advantage is that whereas water absorbs strongly in the infrared region, which limits the pathlengths that can be used and masking large region of the spectrum, the intensity of Raman scattering from water is usually weak and direct absorption interferes only when near-infrared lasers (e.g., 1064 nm) are used. Therefore, water is an ideal solvent. However, since the laser is focused to a relatively small spot size, rapid heating of samples can occur. When resonance Raman spectra are recorded, however, sample heating and photo-bleaching can cause damage and a change to the Raman spectrum obtained. Furthermore, if the absorbance of the sample is high (> OD 2) over the wavelength range in which the Raman spectrum is recorded then inner-filter effects (reabsorption of the Raman scattering by the sample) can decrease signal intensity dramatically. Typically, the sample is placed into a tube, which can then be spun to decrease the sample's exposure to the laser light, and reduce the effects of photodegradation. Gaseous, liquid, and solid samples can all be analyzed using RR spectroscopy.

Although scattered light leaves the sample in all directions the collection of the scattered light is achieved only over a relatively small solid angle by a lens and directed to the spectrograph and CCD detector. The laser beam can be at any angle with respect to the optical axis used to collect Raman scattering. In free space systems, the laser path is typically at an angle of 180° or 135° (a so-called back scattering arrangement). The 180° arrangement is typically used in microscopes and fiber optic based Raman probes. Other arrangements involve the laser passing at 90° with respect to the optical axis. Detection angles of 90° and 0° are less frequently used.

The collected scattered radiation is focused into a spectrograph, in which the light is first collimated and then dispersed by a diffraction grating and refocused onto a CCD camera. The entire spectrum is recorded simultaneously and multiple scans can be acquired in a short period of time, which can increase the signal-to-noise ratio of the spectrum through averaging. Use of this (or equivalent) equipment and following an appropriate protocol[9] can yield better than 10% repeatability in absolute measurements for the rate of Raman scattering. This can be useful with resonance Raman for accurately determining optical transitions in structures with strong Van Hove singularities.[10]

Resonance hyper-Raman spectroscopy

Resonance hyper-Raman spectroscopy is a variation on resonance Raman spectroscopy in which the aim is to achieve an excitation to a particular energy level in the target molecule of the sample by a phenomenon known as two-photon absorption. In two-photon absorption, two photons are simultaneously absorbed into a molecule. When that molecule relaxes from this excited state to its ground state, only one photon is emitted. This is a type of fluorescence.

In resonance Raman spectroscopy, certain parts of molecules can be targeted by adjusting the wavelength of the incident laser beam to the “color” (energy between two desired electron quantum levels) of the part of the molecule that is being studied. This is known as resonance fluorescence, hence the addition of the term “resonance” to the name “Raman spectroscopy”. Some excited states can be achieved via single or double photon absorption. In these cases, however, the use of double photon excitation can be used to attain more information about these excited states than would a single photon absorption. There are some limitations and consequences to both resonance Raman and resonance hyper Raman spectroscopy.[11]

Both resonance Raman and resonance hyper Raman spectroscopy employ a tunable laser. The wavelength of a tunable laser can be adjusted by the operator to wavelengths within a particular range. This frequency range, however, is dependent on the laser’s design. Regular resonance Raman spectroscopy, therefore, is only sensitive to the electron energy transitions that match that of the laser used in the experiment. The molecular parts that can be studied by normal resonance Raman spectroscopy is therefore limited to those bonds that happen to have a “color” that fits somewhere into the spectrum of “colors” to which the laser used in that particular device can be tuned. Resonance hyper Raman spectroscopy, on the other hand, can excite atoms to emit light at wavelengths outside the laser’s tunable range, thus expanding the range of possible components of a molecule that can be excited and therefore studied.

Resonance hyper Raman spectroscopy is one of the types of “non-linear” Raman spectroscopy. In linear Raman spectroscopy, the amount of energy that goes into the excitation of an atom is the same amount that leaves the electron cloud of that atom when a photon is emitted and the electron cloud relaxes back down to its ground state. The term non-linear signifies reduced emission energy compared to input energy. In other words, the energy into the system no longer matches the energy out of the system. This is due to the fact that the energy input in hyper-Raman spectroscopy is much larger than that of typical Raman spectroscopy. Non-linear Raman spectroscopy tends to be more sensitive than conventional Raman spectroscopy. Additionally, it can significantly reduce, or even eliminate the effects of fluorescence.[12]

X-Ray Raman scattering

In the X-ray region, enough energy is available for making electronic transitions possible. At core level resonances, X-ray Raman scattering can become the dominating part of the X-ray fluorescence spectrum. This is due to the resonant behavior of the Kramers-Heisenberg formula in which the denominator is minimized for incident energies that equal a core level. This type of scattering is also known as Resonant inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS). In the soft X-ray range, RIXS has been shown to reflect crystal field excitations, which are often hard to observe with any other technique. Application of RIXS to strongly correlated materials is of particular value for gaining knowledge about their electronic structure. For certain wide band materials such as graphite, RIXS has been shown to (nearly) conserve crystal momentum and thus has found use as a complementary bandmapping technique.

References

- Strommen, Dennis P.; Nakamoto, Kazuo (1977). "Resonance raman spectroscopy". Journal of Chemical Education. 54 (8): 474. Bibcode:1977JChEd..54..474S. doi:10.1021/ed054p474. ISSN 0021-9584.

- Drago, R.S. (1977). Physical Methods in Chemistry. Saunders. p. 152.

- Hu, Songzhou; Smith, Kevin M.; Spiro, Thomas G. (January 1996). "Assignment of Protoheme Resonance Raman Spectrum by Heme Labeling in Myoglobin". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 118 (50): 12638–46. doi:10.1021/ja962239e.

- Yoshikawa, Shinya; Shimada, Atsuhiro; Shinzawa-Itoh, Kyoko (2015). "Chapter 4, Section 3.1 Resonance Raman Analysis". In Peter M.H. Kroneck and Martha E. Sosa Torres (ed.). Sustaining Life on Planet Earth: Metalloenzymes Mastering Dioxygen and Other Chewy Gases. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. 15. Springer. pp. 89–102. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-12415-5_4. ISBN 978-3-319-12414-8. PMID 25707467.

- Hirakawa, A. Y.; Tsuboi, M. (1975-04-25). "Molecular Geometry in an Excited Electronic State and a Preresonance Raman Effect". Science. 188 (4186): 359–361. doi:10.1126/science.188.4186.359. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17807877.

- Clark, Robin J. H.; Dines, Trevor J. (1986). "Resonance Raman Spectroscopy, and Its Application to Inorganic Chemistry". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 25 (2): 131–158. doi:10.1002/anie.198601311. ISSN 0570-0833.

- McHale, Jeanne L. (2002). "Resonance Raman Spectroscopy". Handbook of Vibrational Spectroscopy. 1. Chichester: Wiley. pp. 535–556. ISBN 0471988472.

- Bell, Steven E. J. (1996). "Tutorial review. Time-resolved resonance Raman spectroscopy". The Analyst. 121 (11): 107R. doi:10.1039/an996210107r. ISSN 0003-2654.

- Smith, David C.; Spencer, Joseph H.; Sloan, Jeremy; McDonnell, Liam P.; Trewhitt, Harrison; Kashtiban, Reza J.; Faulques, Eric (2016-04-28). "Resonance Raman Spectroscopy of Extreme Nanowires and Other 1D Systems". Journal of Visualized Experiments (110): 53434. doi:10.3791/53434. ISSN 1940-087X. PMC 4942019. PMID 27168195.

- Spencer, Joseph H.; Nesbitt, John M.; Trewhitt, Harrison; Kashtiban, Reza J.; Bell, Gavin; Ivanov, Victor G.; Faulques, Eric; Sloan, Jeremy; Smith, David C. (2014-09-23). "Raman Spectroscopy of Optical Transitions and Vibrational Energies of ∼1 nm HgTe Extreme Nanowires within Single Walled Carbon Nanotubes" (PDF). ACS Nano. 8 (9): 9044–9052. doi:10.1021/nn5023632. ISSN 1936-0851. PMID 25163005.

- Kelley, Anne Myers (2010). "Hyper-Raman Scattering by Molecular Vibrations". Annual Review of Physical Chemistry. 61 (1): 41–61. doi:10.1146/annurev.physchem.012809.103347. ISSN 0066-426X. PMID 20055673.

- "Raman: Application". 2 October 2013.

Further reading

- Long, Derek A (2002). The Raman Effect: A Unified Treatment of the Theory of Raman Scattering by Molecules. Wiley. ISBN 978-0471490289.

- Que, Lawrence Jr., ed. (2000). Physical Methods in Bioinorganic Chemistry: Spectroscopy and Magnetism. Sausalito, CA: University Science Books. pp. 59–120. ISBN 978-1-891389-02-3.

- Raman, C.V.; Krishnan, K.S. (1928). "A Change of Wave-Length in Light Scattering". Nature. 121 (3051): 619. Bibcode:1928Natur.121..619R. doi:10.1038/121619b0.

- Raman, C.V.; Krishnan, K.S. (1928). "A New Type of Secondary Radiation". Nature. 121 (3048): 501–502. Bibcode:1928Natur.121..501R. doi:10.1038/121501c0.

- Skoog, Douglas A.; Holler, James F.; Nieman, Timothy A. (1998). Principles of Instrumental Analysis (5th ed.). Saunders. pp. 429–443. ISBN 978-0-03-002078-0.

- Landsberg, G.S; Mandelshtam, L.I. (1928). "Novoye yavlenie pri rasseyanii sveta. (New phenomenon in light scattering)". Zhurnal Russkogo Fiziko-khimicheskogo Obschestva, Chast Fizicheskaya (Journal of Russian Physico-Chemical Society, Physics Division: 60–4.

- Chao, R.S.; Khanna, R.K.; Lippincott, E.R. (1975). "Theoretical and experimental resonance Raman intensities for the manganate ion". Journal of Raman Spectroscopy. 3 (2–3): 121–131. Bibcode:1975JRSp....3..121C. doi:10.1002/jrs.1250030203.

External links

- http://chemwiki.ucdavis.edu/Physical_Chemistry/Spectroscopy/Vibrational_Spectroscopy/Raman_Spectroscopy/Raman%3A_Interpretation

- http://www.horiba.com/us/en/scientific/products/Raman-spectroscopy/Raman-academy/Raman-faqs/what-is-polarised-Raman-spectroscopy/

- Kelley, A.M. "Resonance hyper-Raman spectroscopy". University of California, Merced.