Reputation of William Shakespeare

In his own time, William Shakespeare (1564–1616) was rated as merely one among many talented playwrights and poets, but since the late 17th century has been considered the supreme playwright and poet of the English language.

No other dramatist's work has been performed even remotely as often on the world stage as Shakespeare. The plays have often been drastically adapted in performance. During the 18th and 19th centuries, the era of the great acting stars, to be a star on the British stage was synonymous with being a great Shakespearean actor. Then the emphasis was placed on the soliloquies as declamatory turns at the expense of pace and action, and Shakespeare's plays seemed in peril of disappearing beneath the added music, scenery, and special effects produced by thunder, lightning, and wave machines.

Editors and critics of the plays, disdaining the showiness and melodrama of Shakespearean stage representation, began to focus on Shakespeare as a dramatic poet, to be studied on the printed page rather than in the theatre. The rift between Shakespeare on the stage and Shakespeare on the page was at its widest in the early 19th century, at a time when both forms of Shakespeare were hitting peaks of fame and popularity: theatrical Shakespeare was successful spectacle and melodrama for the masses, while book or closet drama Shakespeare was being elevated by the reverential commentary of the Romantics into unique poetic genius, prophet, and bard. Before the Romantics, Shakespeare was simply the most admired of all dramatic poets, especially for his insight into human nature and his realism, but Romantic critics such as Samuel Taylor Coleridge refactored him into an object of almost religious adoration, George Bernard Shaw coining the term "bardolatry" to describe it. These critics regarded Shakespeare as towering above other writers, and regarding his plays not as "merely great works of art" but as "phenomena of nature, like the sun and the sea, the stars and the flowers" and "with entire submission of our own faculties" (Thomas De Quincey, 1823). To the later 19th century, Shakespeare became in addition an emblem of national pride, the crown jewel of English culture, and a "rallying-sign", as Thomas Carlyle wrote in 1841, for the whole British empire.

17th century

Jacobean and Caroline

It is difficult to assess Shakespeare's reputation in his own lifetime and shortly after. England had little modern literature before the 1570s, and detailed critical commentaries on modern authors did not begin to appear until the reign of Charles I. The facts about his reputation can be surmised from fragmentary evidence. He was included in some contemporary lists of leading poets, but he seems to have lacked the stature of the aristocratic Philip Sidney, who became a cult figure due to his death in battle at a young age, or of Edmund Spenser. Shakespeare's poems were reprinted far more frequently than his plays; but Shakespeare's plays were written for performance by his own company, and because no law prevented rival companies from using the plays, Shakespeare's troupe took steps to prevent his plays from being printed. That many of his plays were pirated suggests his popularity in the book market, and the regular patronage of his company by the court, culminating in 1603 when James I turned it into the "King's Men," suggests his popularity among higher stations of society. Modern plays (as opposed to those in Latin and Greek) were considered ephemeral and even somewhat disreputable entertainments by some contemporaries; the new Bodleian Library explicitly refused to shelve plays. Some of Shakespeare's plays, particularly the history plays, were reprinted frequently in cheap quarto (i.e. pamphlet) form; others took decades to reach a 3rd edition.

After Ben Jonson pioneered the canonisation of modern plays by printing his own works in folio (the luxury book format) in 1616, Shakespeare was the next playwright to be honoured by a folio collection, in 1623. That this folio went into another edition within 9 years indicates he was held in unusually high regard for a playwright. The dedicatory poems by Ben Jonson and John Milton in the 2nd folio were the first to suggest Shakespeare was the supreme poet of his age. These expensive reading editions are the first visible sign of a rift between Shakespeare on the stage and Shakespeare for readers, a rift that was to widen over the next two centuries. In his 1630 work 'Timber' or 'Discoveries', Ben Jonson praised the speed and ease with which Shakespeare wrote his plays as well as his contemporary's honesty and gentleness towards others.

Interregnum and Restoration

During the Interregnum (1642–1660), all public stage performances were banned by the Puritan rulers. Though denied the use of the stage, costumes and scenery, actors still managed to ply their trade by performing "drolls" or short pieces of larger plays that usually ended with some type of jig. Shakespeare was among the many playwrights whose works were plundered for these scenes. Among the most common scenes were Bottom's scenes from A Midsummer Night's Dream and the gravedigger's scene from Hamlet. When the theatres opened again in 1660 after this uniquely long and sharp break in British theatrical history, two newly licensed London theatre companies, the Duke's and the King's Company, started business with a scramble for performance rights to old plays. Shakespeare, Ben Jonson, and the Beaumont and Fletcher team were among the most valuable properties and remained popular after Restoration playwriting had gained momentum.

In the elaborate Restoration London playhouses, designed by Christopher Wren, Shakespeare's plays were staged with music, dancing, thunder, lightning, wave machines, and fireworks. The texts were "reformed" and "improved" for the stage. A notorious example is Irish poet Nahum Tate's happy-ending King Lear (1681) (which held the stage until 1838), while The Tempest was turned into an opera replete with special effects by William Davenant. In fact, as the director of the Duke's Company, Davenant was legally obliged to reform and modernise Shakespeare's plays before performing them, an ad hoc ruling by the Lord Chamberlain in the battle for performance rights which "sheds an interesting light on the many 20th-century denunciations of Davenant for his adaptations".[1] The modern view of the Restoration stage as the epitome of Shakespeare abuse and bad taste has been shown by Hume to be exaggerated, and both scenery and adaptation became more reckless in the 18th and 19th centuries.

The incomplete Restoration stage records suggest Shakespeare, although always a major repertory author, was bested in the 1660–1700 period by the phenomenal popularity of Beaumont and Fletcher. "Their plays are now the most pleasant and frequent entertainments of the stage", reported fellow playwright John Dryden in 1668, "two of theirs being acted through the year for one of Shakespeare's or Jonson's". In the early 18th century, however, Shakespeare took over the lead on the London stage from Beaumont and Fletcher, never to relinquish it again.

By contrast to the stage history, in literary criticism there was no lag time, no temporary preference for other dramatists: Shakespeare had a unique position at least from the Restoration in 1660 and onwards. While Shakespeare did not follow the unbending French neo-classical "rules" for the drama and the three classical unities of time, place, and action, those strict rules had never caught on in England, and their sole zealous proponent Thomas Rymer was hardly ever mentioned by influential writers except as an example of narrow dogmatism. Dryden, for example, argued in his influential Essay of Dramatick Poesie (1668) – the same essay in which he noted that Shakespeare's plays were performed only half as often as those of Beaumont and Fletcher – for Shakespeare's artistic superiority. Though Shakespeare does not follow the dramatic conventions, Dryden wrote, Ben Jonson does, and as a result Jonson lands in a distant second place to "the incomparable Shakespeare", the follower of nature, the untaught genius, the great realist of human character.

18th century

Britain

In the 18th century, Shakespeare dominated the London stage, while Shakespeare productions turned increasingly into the creation of star turns for star actors. After the Licensing Act of 1737, a quarter of plays performed were by Shakespeare, and on at least two occasions rival London playhouses staged the very same Shakespeare play at the same time (Romeo and Juliet in 1755 and King Lear the next year) and still commanded audiences. This occasion was a striking example of the growing prominence of Shakespeare stars in the theatrical culture, the big attraction being the competition and rivalry between the male leads at Covent Garden and Drury Lane, Spranger Barry and David Garrick. There appears to have been no issues with Barry and Garrick, in their late thirties, playing adolescent Romeo one season and geriatric King Lear the next. In September 1769 Garrick staged a major Shakespeare Jubilee in Stratford-upon-Avon which was a major influence on the rise of bardolatry.[2][3]

As performance playscripts diverged increasingly from their originals, the publication of texts intended for reading developed rapidly in the opposite direction, with the invention of textual criticism and an emphasis on fidelity to Shakespeare's original words. The texts that we read and perform today were largely settled in the 18th century. Nahum Tate and Nathaniel Lee had already prepared editions and performed scene divisions in the late 17th century, and Nicholas Rowe's edition of 1709 is considered the first truly scholarly text for the plays. It was followed by many good 18th-century editions, crowned by Edmund Malone's landmark Variorum Edition, which was published posthumously in 1821 and remains the basis of modern editions. These collected editions were meant for reading, not staging; Rowe's 1709 edition was, compared to the old folios, a light pocketbook. Shakespeare criticism also increasingly spoke to readers, rather than to theatre audiences.

The only aspects of Shakespeare's plays that were consistently disliked and singled out for criticism in the 18th century were the puns ("clenches") and the "low" (sexual) allusions. While a few editors, notably Alexander Pope, attempted to gloss over or remove the puns and the double entendres, they were quickly reversed, and by mid-century the puns and sexual humour were (with only a few exceptions, see Thomas Bowdler) back in permanently.

Dryden's sentiments about Shakespeare's imagination and capacity for painting "nature" were echoed in the 18th century by, for example, Joseph Addison ("Among the English, Shakespeare has incomparably excelled all others"), Alexander Pope ("every single character in Shakespeare is as much an Individual as those in Life itself"), and Samuel Johnson (who scornfully dismissed Voltaire's and Rhymer's neoclassical Shakespeare criticism as "the petty cavils of petty minds"). The long-lived belief that the Romantics were the first generation to truly appreciate Shakespeare and to prefer him to Ben Jonson is contradicted by praise from writers throughout the 18th century. Ideas about Shakespeare that many people think of as typically post-Romantic were frequently expressed in the 18th and even in the 17th century: he was described as a genius who needed no learning, as deeply original, and as creating uniquely "real" and individual characters (see Timeline of Shakespeare criticism). To compare Shakespeare and his well-educated contemporary Ben Jonson was a popular exercise at this time, a comparison that was invariably complimentary to Shakespeare. It functioned to highlight the special qualities of both writers, and it especially powered the assertion that natural genius trumps rules, that "there is always an appeal open from criticism to nature" (Samuel Johnson).

Opinion of Shakespeare was briefly shaped in the 1790s by the "discovery" of the Shakespeare Papers by William Henry Ireland. Ireland claimed to have found in a trunk a goldmine of lost documents of Shakespeare's including two plays, Vortigern and Rowena and Henry II. These documents appeared to demonstrate a number of unknown facts about Shakespeare that shaped opinion of his works, including a Profession of Faith demonstrating Shakespeare was a Protestant and that he had an illegitimate child. Although there were many believers in the provenance of the Papers they soon came under fierce attack from scholars who pointed out numerous inaccuracies. Vortigern had only one performance at the Drury Lane Theatre before Ireland admitted he had forged the documents and written the plays himself.[4]

In Germany

English actors started visiting the Holy Roman Empire in the late 16th century to work as "fiddlers, singers and jugglers", and through them the work of Shakespeare had first become known in the Reich.[5] In 1601, in the Free City of Danzig (modern Gdańsk, Poland), which had a large English merchant colony living within its walls, a company of English actors arrived to put on plays by Shakespeare.[6] By 1610, the actors were performing Shakespeare in German as his plays had become popular in Danzig.[7] Some of Shakespeare's work was performed in continental Europe during the 17th century, but it was not until the mid 18th century that it became widely known. In Germany Lessing compared Shakespeare to German folk literature. In France, the Aristotelian rules were rigidly obeyed, and in Germany, a land where French cultural influence was very strong (German elites preferred to speak French rather than German in the 18th century), the Francophile German theatre critics had long denounced Shakespeare's work as a "jumble" that violated all the Aristotelian rules.[8]

As a part of an effort to get the German public to take Shakespeare more seriously, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe organised a Shakespeare jubilee in Frankfurt in 1771, stating in a speech on 14 October 1771 that the dramatist had shown that the Aristotelian unities were "as oppressive as a prison" and were "burdensome fetters on our imagination". Goethe praised Shakespeare for liberating his mind from the rigid Aristoltelian rules, saying: "I jumped into the free air, and suddenly felt I had hands and feet...Shakespeare, my friend, if you were with us today, I could only live with you".[9] Herder likewise proclaimed that reading Shakespeare's work opens "leaves from the book of events, of providence, of the world, blowing in the sands of time".

This claim that Shakespeare's work breaks through all creative boundaries to reveal a chaotic, teeming, contradictory world became characteristic of Romantic criticism, later being expressed by Victor Hugo in the preface to his play Cromwell, in which he lauded Shakespeare as an artist of the grotesque, a genre in which the tragic, absurd, trivial and serious were inseparably intertwined. In 1995, the American journalist Stephen Kinzer writing in The New York Times observed: "Shakespeare is an all-but-guaranteed success in Germany, where his work has enjoyed immense popularity for more than 200 years. By some estimates, Shakespeare's plays are performed more frequently in Germany than anywhere else in the world, not excluding his native England. The market for his work, both in English and in German translation, seems inexhaustible."[10] The German critic Ernst Osterkamp wrote: "Shakespeare's importance to German literature cannot be compared with that of any other writer of the post-antiquity period. Neither Dante or Cervantes, neither Moliere or Ibsen have even approached his influence here. With the passage of time, Shakespeare has virtually become one of Germany's national authors."[11]

In Russia

Shakespeare as far it can be established never went any further from Stratford-upon-Avon than London, but he made a reference to the visit of Russian diplomats from the court of Tsar Ivan the Terrible to the court of Elizabeth I in Love Labor Lost in which the French aristocrats dress up as Russians and make fools of themselves."[12] Shakespeare was first translated into Russian by Alexander Sumarokov, who called Shakespeare an "inspired barbarian", who wrote of the Bard of Avon that in his plays “there is much that is bad and exceedingly good”.[13] In 1786, Shakespeare's reputation in Russia was greatly enhanced when the Empress Catherine the Great translated a French version of The Merry Wives of Windsor into Russian (Catherine did not know English) and had it staged in St. Petersburg.[14] Shortly afterwards, Catherine translated Timon of Athens from French into Russian.[15] The patronage of Catherine made Shakespeare an eminently respectable author in Russia, but his plays were rarely performed until the 19th century, and instead he was widely read.[16]

19th century

Shakespeare in performance

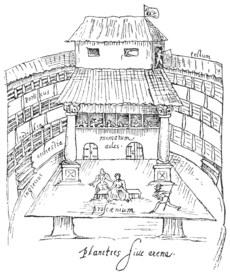

Theatres and theatrical scenery became ever more elaborate in the 19th century, and the acting editions used were progressively cut and restructured to emphasise more and more the soliloquies and the stars, at the expense of pace and action.[17] Performances were further slowed by the need for frequent pauses to change the scenery, creating a perceived need for even more cuts to keep performance length within tolerable limits; it became a generally accepted maxim that Shakespeare's plays were too long to be performed without substantial cuts. The platform, or apron, stage, on which actors of the 17th century would come forward for audience contact, was gone, and the actors stayed permanently behind the fourth wall or proscenium arch, further separated from the audience by the orchestra, see image right.

Through the 19th century, a roll call of legendary actors' names all but drown out the plays in which they appear: Sarah Siddons (1755—1831), John Philip Kemble (1757—1823), Henry Irving (1838—1905), and Ellen Terry (1847—1928). To be a star of the legitimate drama came to mean being first and foremost a "great Shakespeare actor", with a famous interpretation of, for men, Hamlet, and for women, Lady Macbeth, and especially with a striking delivery of the great soliloquies. The acme of spectacle, star, and soliloquy Shakespeare performance came with the reign of actor-manager Henry Irving at the Royal Lyceum Theatre in London from 1878–99. At the same time, a revolutionary return to the roots of Shakespeare's original texts, and to the platform stage, absence of scenery, and fluid scene changes of the Elizabethan theatre, was being effected by William Poel's Elizabethan Stage Society.

Shakespeare in criticism

The belief in the unappreciated 18th-century Shakespeare was proposed at the beginning of the 19th century by the Romantics, in support of their view of 18th-century literary criticism as mean, formal, and rule-bound, which was contrasted with their own reverence for the poet as prophet and genius. Such ideas were most fully expressed by German critics such as Goethe and the Schlegel brothers. Romantic critics such as Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Hazlitt raised admiration for Shakespeare to worship or even "bardolatry" (a sarcastic coinage from bard + idolatry by George Bernard Shaw in 1901, meaning excessive or religious worship of Shakespeare). To compare him to other Renaissance playwrights at all, even for the purpose of finding him superior, began to seem irreverent. Shakespeare was rather to be studied without any involvement of the critical faculty, to be addressed or apostrophised—almost prayed to—by his worshippers, as in Thomas De Quincey's classic essay "On the Knocking at the Gate in Macbeth" (1823): "O, mighty poet! Thy works are not as those of other men, simply and merely great works of art; but are also like the phenomena of nature, like the sun and the sea, the stars and the flowers,—like frost and snow, rain and dew, hail-storm and thunder, which are to be studied with entire submission of our own faculties...".

As the concept of literary originality grew in importance, critics were horrified at the idea of adapting Shakespeare's tragedies for the stage by putting happy endings on them, or editing out the puns in Romeo and Juliet. In another way, what happened on the stage was seen as unimportant, as the Romantics, themselves writers of closet drama, considered Shakespeare altogether more suitable for reading than staging. Charles Lamb saw any form of stage representation as distracting from the true qualities of the text. This view, argued as a timeless truth, was also a natural consequence of the dominance of melodrama and spectacle on the early 19th-century stage.

Shakespeare became an important emblem of national pride in the 19th century, which was the heyday of the British Empire and the acme of British power in the world. To Thomas Carlyle in On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History (1841), Shakespeare was one of the great poet-heroes of history, in the sense of being a "rallying-sign" for British cultural patriotism all over the world, including even the lost American colonies: "From Paramatta, from New York, wheresoever... English men and women are, they will say to one another, 'Yes, this Shakespeare is ours; we produced him, we speak and think by him; we are of one blood and kind with him'" ("The Hero as a Poet"). As the foremost of the great canonical writers, the jewel of English culture, and as Carlyle puts it, "merely as a real, marketable, tangibly useful possession", Shakespeare became in the 19th century a means of creating a common heritage for the motherland and all her colonies. Post-colonial literary critics have had much to say of this use of Shakespeare's plays in what they regard as a move to subordinate and deracinate the cultures of the colonies themselves. Across the North Sea, Shakespeare remained influential in Germany. In 1807, August Wilhelm Schlegel translated all of Shakespeare's plays into German, and such was the popularity of Schlegel's translation (which is generally regarded as one of the best translations of Shakespeare into any language) that German nationalists were soon starting to claim that Shakespeare was actually a German playwright who just written his plays in English.[18] By the middle of the 19th century, Shakespeare had been incorporated into the pantheon of German literature.[19] In 1904, a statue of Shakespeare was erected in Weimar showing the Bard of Avon staring into the distance, becoming the first statue built to honor Shakespeare on the mainland of Europe.[20]

Romantic icon in Russia

In the Romantic age, Shakespeare became extremely popular in Russia.[21] Vissarion Belinsky wrote he had been “enslaved by the drama of Shakespeare”.[22] Russia's national poet, Alexander Pushkin, was heavily influenced by Hamlet and the history plays, and his novel Boris Godunov showed strong Shakespearean influences.[23] Later on, in the 19th century, the novelist Ivan Turgenev often wrote essays on Shakespeare with the best known being “Hamlet and Don Quixote”.[24] Fyodor Dostoevsky was greatly influenced by Macbeth with his novel Crime and Punishment showing Shakespearean influence in his treatment of the theme of guilt.[25] From the 1840s onward, Shakespeare was regularly staged in Russia, and the black American actor Ira Aldridge who had been barred from the stage in the United States on the account of his skin color became the leading Shakespearean actor in Russia in the 1850s, being decorated by the Emperor Alexander II for his work in portraying Shakespearean characters.[26]

20th century

Shakespeare continued to be considered the greatest English writer of all time throughout the 20th century. Most Western educational systems required the textual study of two or more of Shakespeare's plays, and both amateur and professional stagings of Shakespeare were commonplace. It was the proliferation of high-quality, well-annotated texts and the unrivalled reputation of Shakespeare that allowed for stagings of Shakespeare's plays to remain textually faithful, but with an extraordinary variety in setting, stage direction, and costuming. Institutions such as the Folger Shakespeare Library in the United States worked to ensure constant, serious study of Shakespearean texts and the Royal Shakespeare Company in the United Kingdom worked to maintain a yearly staging of at least two plays.

Shakespeare performances reflected the tensions of the times, and early in the century, Barry Jackson of the Birmingham Repertory Theatre began the staging of modern-dress productions, thus starting a new trend in Shakesperian production. Performances of the plays could be highly interpretive. Thus, play directors would emphasise Marxist, feminist, or, perhaps most popularly, Freudian psychoanalytical interpretations of the plays, even as they retained letter-perfect scripts. The number of analytical approaches became more diverse by the latter part of the century, as critics applied theories such as structuralism, New Historicism, Cultural materialism, African American studies, queer studies, and literary semiotics to Shakespeare's works.[27][28]

In the Third Reich

In 1934 the French government banned, in permanence, performances of Coriolanus because of its perceived authoritarian undertones. In the international protests that followed came one from Germany, from none other than Joseph Goebbels. Although productions of Shakespeare's plays in Germany itself were subject to 'streamlining', he continued to be favoured as a great classical dramatist, especially so as almost every new German play since the late 1890s onwards was portrayed by German government propaganda as the work of left-wingers, of Jews or of "degenerates" of one kind or another. Politically acceptable writers had simply been unable to fill the gap, or had only been able to do so with the worst kinds of agitprop. In 1935 Goebbels was to say "We can build autobahns, revive the economy, create a new army, but we... cannot manufacture new dramatists." With Schiller suspect for his radicalism, Lessing for his humanism and even the great Goethe for his lack of patriotism, the legacy of the "Aryan" Shakespeare was reinterpreted for new purposes.

Rodney Symington, Professor of Germanic and Russian Studies at the University of Victoria, Canada, deals with this question in The Nazi Appropriation of Shakespeare: Cultural Politics in the Third Reich (Edwin Mellen Press, 2005). The scholar reports that Hamlet, for instance, was reconceived as a proto-German warrior rather than a man with a conscience. Of this play one critic wrote: "If the courtier Laertes is drawn to Paris and the humanist Horatio seems more Roman than Danish, it is surely no accident that Hamlet's alma mater should be Wittenberg." A leading magazine declared that the crime which deprived Hamlet of his inheritance was a foreshadow of the Treaty of Versailles, and that the conduct of Gertrude was reminiscent of the spineless Weimar politicians.

Weeks after Hitler took power in 1933 an official party publication appeared entitled Shakespeare – a Germanic Writer, a counter to those who wanted to ban all foreign influences. At the Propaganda Ministry, Rainer Schlosser, given charge of German theatre by Goebbels, mused that Shakespeare was more German than English. After the outbreak of the war the performance of Shakespeare was banned, though it was quickly lifted by Hitler in person, a favour extended to no other. Not only did the regime appropriate the Bard but it also appropriated Elizabethan England itself. To the Nazi leaders, it was a young, vigorous nation, much like the Third Reich itself, quite unlike the decadent British Empire of the present day.

Clearly there were some exceptions to the official approval of Shakespeare, and the great patriotic plays, most notably Henry V were shelved. The reception of The Merchant of Venice was at best lukewarm (Marlowe's The Jew of Malta was suggested as a possible alternative) because it was not anti-Semitic enough for Nazi taste (the play's conclusion, in which the daughter of the Jewish antagonist converts to Christianity and marries one of the Gentile protagonists, particularly violated Nazi notions of racial purity). So Hamlet was by far the most popular play, along with Macbeth and Richard III.

In the Soviet Union

Given the popularity of Shakespeare in Russia, there were film versions of Shakespeare that often differed from western interpretations, usually emphasizing a humanist message that implicitly criticized the Soviet regime.[29] Othello (1955) by Sergei Yutkevich celebrated Desdemona's love for Othello as a triumph of love over racial hatred.[30] Hamlet (1964) by Grigori Kozintsev portrayed 16th century Denmark as a dark, gloomy and oppressive place with recurring images of imprisonment marking the film from the focus on the portcullis of Elsinore to the iron corset Ophelia is forced to wear as she goes insane.[31] The tyranny of Claudius resembled the tyranny of Stalin with gigantic portraits and bursts of Claudius being prominent in the background of the film, suggesting that Claudius has engaged in a "cult of personality". Given the emphasis on images of imprisonment, Hamlet's decision to revenge his father becomes almost subsidiary to his struggle for freedom as he challenges the Stalin-like tyranny of Claudius.[32] Hamlet in this film resembles a Soviet dissident who despite his own hesitation, fears and doubts, can no longer stand the moral rot around him. The film was based on a script written by the novelist Boris Pasternak, who had been persecuted under Stalin.[33] The 1971 version of King Lear, also directed by Kozintsev presented the play as a "Tolstoyan panorama of bestiality and courage" as Lear finds his moral redemption amongst the common people.[34]

Acceptance in France

Shakespeare for a variety of reasons had never caught on in France, and even when his plays were performed in France in the 19th century, they were drastically altered to fit in with French tastes with for example Romano and Juliet having a happy ending.[35] Not until 1946 when Hamlet as translated by André Gide was performed in Paris that "ensured Shakespeare's elevation to cult status" in France.[36] The philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre wrote that French intellectuals had been “abruptly reintegrated into history” by the German occupation of 1940–44 as the old teleological history version of history with the world getting progressively better as led by France not longer held, and as such the "nihilist" and "chaotic" plays of Shakespeare finally found an audience in France.[37] The Economist observed: "By the late 1950s, Shakespeare had entered the French soul. No one who has seen the Comédie-Française perform his plays at the Salle Richelieu in Paris is likely to forget the special buzz in the audience, for the bard is the darling of France."[38]

In China

In the years of tentative political and economic liberalization after the death of Mao in 1976, Shakespeare became popular in China.[39] The very act of putting on a play by Shakespeare, formerly condemned as a "bourgeois Western imperialist author" whom no Chinese could respect, was in and of itself an act of quiet dissent.[40] Of all Shakespeare's plays, the most popular in China in the late 1970s and 1980s was Macbeth, as Chinese audiences saw in a play first performed in England in 1606 and set in 11th century Scotland a parallel with the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution of the late 1960s.[41] The violence and bloody chaos of Macbeth reminded Chinese audiences of the violence and bloody chaos of the Cultural Revolution, and furthermore, the story of a national hero becoming a tyrant complete with a power-hungry wife was seen as a parallel with Mao Zedong and his wife, Jiang Qing.[42] Reviewing a production of Macbeth in Beijing in 1980, one Chinese critic, Xu Xiaozhong praised Macbeth as the story of "how the greed for power finally ruined a great man".[43] Another critic, Zhao Xun wrote "Macbeth is the fifth Shakespearean play produced on the Chinese stage after the smashing of the Gang of Four. This play of conspiracy has always been performed at critical moments in the history of our nation".[44]

Likewise, a 1982 production of King Lear was hailed by the critics as the story of "moral decline", of a story "when human beings' souls were so polluted that they even mistreated their aged parents", an allusion to the days of the Cultural Revolution when the young people serving in the Red Guard had berated, denounced, attacked and sometimes even killed their parents for failing to live up to "Mao Zedong thought".[45] The play's director, the Shakespearean scholar Fang Ping who had suffered during the Cultural Revolution for studying this "bourgeois Western imperialist", stated in an interview at the time that King Lear was relevant in China because King Lear, the "highest ruler of a monarchy" created a world full of cruelty and chaos where those who loved him were punished and those who did not were rewarded, a barely veiled reference to the often capricious behavior of Mao, who punished his loyal followers for no apparent reason.[46] Cordeilia's devotion and love for her father-despite his madness, cruelty and rejection of her-is seen in China as affirming traditional Confucian values where love of the family counts above all, and for this reason, King Lear is seen in China as being a very "Chinese" play that affirms the traditional values of filial piety.[47]

A 1981 production of The Merchant of Venice was a hit with Chinese audiences as the play was seen promoting the theme of justice and fairness in life, with the character of Portia being especially popular as she seen as standing for as one critic wrote for "the humanist spirit of the Renaissance" with its striving for "individuality, human rights and freedom".[48] The theme of a religious conflict between a Jewish merchant vs. a Christian merchant in The Merchant of Venice is generally ignored in Chinese productions of The Merchant of Venice as most Chinese find do not find the theme of Jewish-Christian conflict relevant.,[49] Unlike in Western productions, the character of Shylock is very much an unnuanced villain in Chinese productions of The Merchant of Venice, being presented as a man capable only of envy, spite, greed and cruelty, a man whose actions are only motivated by his spiritual impoverishment.[50] By contrast, in the West, Shylock is usually presented as a nuanced villain, of a man who has never held power over a Christian before, and lets that power go to his head.[51] Another popular play, especially with dissidents under the Communist government, is Hamlet.[52] Hamlet, with its theme of a man trapped under a tyrannical regime is very popular with Chinese dissidents with one dissident Wu Ningkun writing about his time in internal exile between 1958–61 at a collective farm in a remote part of northern Manchuria that he understood all too well the line from the play "Denmark is a prison!"[53]

Film

That divergence between text and performance in Shakespeare continued into the new media of film. For instance, both Hamlet and Romeo and Juliet have been filmed in modern settings, sometimes with contemporary "updated" dialogue. Additionally, there were efforts (notably by the BBC) to ensure that there was a filmed or videotaped version of every Shakespeare play. The reasoning for this was educational, as many government educational initiatives recognised the need to get performative Shakespeare into the same classrooms as the read plays.

Poetry

Many English-language Modernist poets drew on Shakespeare's works, interpreting in new ways. Ezra Pound, for instance, considered the Sonnets as a kind of apprentice work, with Shakespeare learning the art of poetry through writing them. He also declared the History plays to be the true English epic. Basil Bunting rewrote the sonnets as modernist poems by simply erasing all the words he considered unnecessary. Louis Zukofsky had read all of Shakespeare's works by the time he was eleven, and his Bottom: On Shakespeare (1947) is a book-length prose poem exploring the role of the eye in the plays. In its original printing, a second volume consisting of a setting of The Tempest by the poet's wife, Celia Zukofsky was also included.

Critical quotations

The growth of Shakespeare's reputation is illustrated by a timeline of Shakespeare criticism, from John Dryden's "when he describes any thing, you more than see it, you feel it too" (1668) to Thomas Carlyle's estimation of Shakespeare as the "strongest of rallying-signs" (1841) for an English identity.

Notes

- (Hume, p. 20)

- McIntyre, Ian (1999). Garrick. London: Penguin. p. 432. ISBN 0-14-028323-4.

- Pierce pp. 4–10

- Pierce pp. 137–181

- Buruma, Ian Anglomania: A European Love Affair, New York: Vintage Books, 1998 p. 52.

- Easton, Adam (19 September 2014). "Gdansk theatre reveals Poland's ties to Shakespeare". The BBC. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- Easton, Adam (19 September 2014). "Gdansk theatre reveals Poland's ties to Shakespeare". The BBC. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- Buruma, Ian Anglomania: A European Love Affair, New York: Vintage Books, 1998 p. 57.

- Buruma, Ian Anglomania: A European Love Affair, New York: Vintage Books, 1998 p. 57.

- Kinzer, Stephen (30 December 1995). "Shakespeare, Icon in Germany". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- Kinzer, Stephen (30 December 1995). "Shakespeare, Icon in Germany". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- Dickson, Andrew (May 2012). "As they like it: Shakespeare in Russia". The Calvert Journal. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- Dickson, Andrew (May 2012). "As they like it: Shakespeare in Russia". The Calvert Journal. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- Dickson, Andrew (May 2012). "As they like it: Shakespeare in Russia". The Calvert Journal. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- Dickson, Andrew (May 2012). "As they like it: Shakespeare in Russia". The Calvert Journal. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- Dickson, Andrew (May 2012). "As they like it: Shakespeare in Russia". The Calvert Journal. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- See, for example, the 19th century playwright W. S. Gilbert's essay, Unappreciated Shakespeare, from Foggerty's Fairy and Other Tales

- Buruma, Ian Anglomania: A European Love Affair, New York: Vintage Books, 1998 p. 51.

- Buruma, Ian Anglomania: A European Love Affair, New York: Vintage Books, 1998 p. 51.

- Kinzer, Stephen (30 December 1995). "Shakespeare, Icon in Germany". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- Dickson, Andrew (May 2012). "As they like it: Shakespeare in Russia". The Calvert Journal. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- Dickson, Andrew (May 2012). "As they like it: Shakespeare in Russia". The Calvert Journal. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- Dickson, Andrew (May 2012). "As they like it: Shakespeare in Russia". The Calvert Journal. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- Dickson, Andrew (May 2012). "As they like it: Shakespeare in Russia". The Calvert Journal. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- Dickson, Andrew (May 2012). "As they like it: Shakespeare in Russia". The Calvert Journal. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- Dickson, Andrew (May 2012). "As they like it: Shakespeare in Russia". The Calvert Journal. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- Grady, Hugh (2001). "Modernity, Modernism and Postmodernism in the Twentieth Century's Shakespeare". In Bristol, Michael; McLuskie, Kathleen (eds.). Shakespeare and Modern Theatre: The Performance of Modernity. New York: Routledge. p. 29. ISBN 0-415-21984-1.

- Drakakis, John (1985). Drakakis, John (ed.). Alternative Shakespeares. New York: Meuthen. pp. 16–17, 23–25. ISBN 0-416-36860-3.

- Howard, Tony "Shakespeare on film and video" pp. 607–619 from Shakespeare An Oxford Guide, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003 p. 611.

- Howard, Tony "Shakespeare on film and video" pp. 607–619 from Shakespeare An Oxford Guide, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003 p. 611.

- Howard, Tony "Shakespeare on film and video" pp. 607–619 from Shakespeare An Oxford Guide, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003 p. 611.

- Howard, Tony "Shakespeare on film and video" pp. 607–619 from Shakespeare An Oxford Guide, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003 page 611.

- Howard, Tony "Shakespeare on film and video" pp. 607–619 from Shakespeare An Oxford Guide, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003 p. 611.

- Howard, Tony "Shakespeare on film and video" pp. 607–619 from Shakespeare An Oxford Guide, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003 p. 611.

- "French hissing". The Economist. 31 March 2002. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- "French hissing". The Economist. 31 March 2002. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- "French hissing". The Economist. 31 March 2002. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- "French hissing". The Economist. 31 March 2002. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- Chen, Xiaomei Occidentalism, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995 pp. 51–52.

- Chen, Xiaomei Occidentalism, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995 p. 51.

- Chen, Xiaomei Occidentalism, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995 p. 51.

- Chen, Xiaomei Oiccidentalism, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995 p. 52.

- Chen, Xiaomei Occidentalism, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995 p. 52.

- Chen, Xiaomei Occidentalism, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995 p. 52.

- Chen, Xiaomei Occidentalism, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995 p. 54.

- Chen, Xiaomei Occidentalism, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995 p. 54.

- Chen, Xiaomei Occidentalism, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995 pp. 54–55.

- Chen, Xiaomei Occidentalism, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995 p. 55.

- Chen, Xiaomei Occidentalism, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995 p. 55.

- Chen, Xiaomei Occidentalism, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995 p. 55.

- Chen, Xiaomei Occidentalism, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995 p. 55.

- Chen, Xiaomei Occidentalism, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995 p. 55.

- Chen, Xiaomei Occidentalism, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995 p. 55.

References

- Hawkes, Terence. (1992) Meaning by Shakespeare. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-07450-9.

- Hume, Robert D. (1976). The Development of English Drama in the Late Seventeenth Century. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-812063-X.

- Lynch, Jack (2007). Becoming Shakespeare: The Strange Afterlife That Turned a Provincial Playwright into the Bard. New York: Walker & Co.

- Marder, Louis. (1963). His Exits and His Entrances: The Story of Shakespeare's Reputation. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott.

- Pierce, Patricia. The Great Shakespeare Fraud: The Strange, True Story of William-Henry Ireland. Sutton Publishing, 2005.

- Sorelius, Gunnar. (1965). "The Giant Race Before the Flood": Pre-Restoration Drama on the Stage and in the Criticism of the Restoration. Uppsala: Studia Anglistica Upsaliensia.

- Speaight, Robert. (1954) William Poel and the Elizabethan revival. Published for The Society for Theatre Research. London: Heinemann.

External links

Audiobook

E-texts (chronological)

- Ben Jonson on Shakespeare (1630)

- John Dryden, Essay of Dramatic Poesy, (1668)

- Thomas Rhymer's notorious attack on Othello, 1692 (at Angelfire website) , which in the end did Shakespeare's reputation more good than harm, by firing up John Dryden, John Dennis and other influential critics into writing eloquent replies.

- Alexander Pope, Preface to his Works of Shakespear (1725)

- Thomas De Quincey, "On the Knocking at the Gate in Macbeth" (1823)

- Thomas Carlyle, On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History (1841)

Other resources

- PeoplePlay UK Shakespeare performance timeline

- Shakespeare biography and online resources at NoSweatShakespeare

- The Shakespeare Resource Center A directory of Web resources for online Shakespearean study. Includes a Shakespeare biography, works timeline, play synopses, and language resources.

.png)