Rear Window

Rear Window is a 1954 American mystery thriller film directed by Alfred Hitchcock and written by John Michael Hayes based on Cornell Woolrich's 1942 short story "It Had to Be Murder". Originally released by Paramount Pictures, the film stars James Stewart, Grace Kelly, Wendell Corey, Thelma Ritter, and Raymond Burr. It was screened at the 1954 Venice Film Festival.

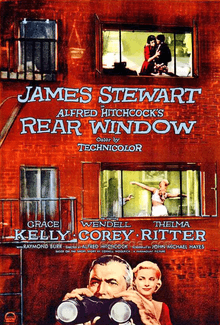

| Rear Window | |

|---|---|

Original theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Alfred Hitchcock |

| Produced by | Alfred Hitchcock |

| Screenplay by | John Michael Hayes |

| Based on | "It Had to Be Murder" by Cornell Woolrich |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Franz Waxman |

| Cinematography | Robert Burks |

| Edited by | George Tomasini |

Production company | Patron Inc. |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 112 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1 million[1] |

| Box office | $36.8 million[2] |

The film is considered by many filmgoers, critics, and scholars to be one of Hitchcock's best[3] and one of the greatest films ever made. It received four Academy Award nominations and was ranked number 42 on AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies list and number 48 on the 10th-anniversary edition, and in 1997 was added to the United States National Film Registry in the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[4] [5]

Plot

Recuperating from a broken leg, adventuresome professional photographer L. B. "Jeff" Jefferies is confined to a wheelchair in his apartment in Chelsea, Manhattan. His rear window looks out onto a courtyard and several other apartments. During an intense heat wave, he watches his neighbors, who keep their windows open to stay cool.

He observes a flamboyant dancer he nicknames "Miss Torso"; a single woman he calls "Miss Lonelyhearts"; a talented, single, composer-pianist; several married couples, one of them newlyweds; a middle-aged couple with a small dog that likes digging in the flower garden; a female amateur sculptor; and Lars Thorwald, a traveling jewelry salesman with a bedridden wife.

Jeff's sophisticated, beautiful socialite girlfriend, Lisa Fremont, visits him regularly, as does the insurance company nurse, Stella. Stella thinks Jeff should settle down and marry Lisa, but Jeff is reluctant due to their disparate lifestyles.

One night during a thunderstorm, Jeff hears a woman scream, "Don't!" and then the sound of breaking glass. Later, he is awakened by thunder and observes Thorwald leaving his apartment, carrying a suitcase in pouring rain. Thorwald makes repeated late-night trips carrying the case. The next morning, Jeff notices that Thorwald's wife is gone, and then sees Thorwald cleaning a large knife and handsaw. Later, Thorwald has moving men haul away a large trunk he tied with rope. Jeff shares all this with Lisa and with Stella, who both think he has an overactive imagination, but come to believe him when they observe Thorwald acting suspiciously.

Jeff becomes convinced that Thorwald has murdered his wife. Jeff calls his friend Tom Doyle, a New York City Police detective, and asks him to investigate Thorwald. Doyle finds nothing suspicious; apparently, Mrs. Thorwald is upstate, and picked up the trunk herself.

Soon after, the neighbor's dog is found dead with its neck broken. The distraught owner yells across the courtyard, wailing about her neighbors' callous disregard. Everyone runs to their windows to see what is happening, except for Thorwald, whose cigar is seen glowing as he sits quietly in his dark apartment.

Certain Thorwald killed the dog, Jeff has Lisa slip an accusatory note under his door so he can observe Thorwald's reaction reading it. As a pretext to get Thorwald out of his apartment, Jeff then telephones him and arranges a meeting at a bar. He believes Thorwald buried something incriminating in the courtyard flower bed, and killed the dog to stop it digging there. When Thorwald leaves, Lisa and Stella dig up the flowers but find nothing.

Much to Jeff's amazement and admiration, Lisa climbs up the fire escape to Thorwald's apartment and clambers in through an open window. When Thorwald returns and confronts Lisa, Jeff calls the police, who arrive in time, arresting her when Thorwald indicates that she broke in. Jeff sees Lisa's hands behind her back, pointing to her finger with Mrs. Thorwald's wedding ring on it. Thorwald also sees this, and, realizing that she is signaling someone, spots Jeff across the courtyard.

Jeff phones Doyle and leaves an urgent message while Stella goes to bail Lisa out of jail. When his phone rings, Jeff assumes it is Doyle, and blurts out that the suspect has left the apartment. When no one answers, Jeff realizes that Thorwald himself called and is coming to confront him. When Thorwald enters, Jeff repeatedly sets off his camera flashbulbs, temporarily blinding him. Thorwald grabs Jeff and pushes him out the open window, as Jeff, hanging on, yells for help. Police enter the apartment as Jeff falls; officers on the ground run over and break his fall. Thorwald confesses to the police soon afterward.

A few days later, the heat has lifted, and Jeff rests peacefully in his wheelchair, now with casts on both legs. The lonely neighbor is chatting with the pianist in his apartment, the dancer's boyfriend returns home from the army, the couple whose dog was killed have a new puppy, and the newlyweds are bickering.

Lisa reclines on the daybed in Jeff's apartment, wearing jeans, reading a book titled, Beyond the High Himalayas. After seeing that Jeff is sleeping, Lisa happily opens a fashion magazine.

Cast

- James Stewart as L. B. "Jeff" Jefferies

- Grace Kelly as Lisa Carol Fremont

- Wendell Corey as NYPD Det. Lt. Thomas "Tom" J. Doyle

- Thelma Ritter as Stella

- Raymond Burr as Lars Thorwald

- Judith Evelyn as Miss Lonelyhearts

- Ross Bagdasarian as the songwriter

- Georgine Darcy as Miss Torso

- Sara Berner and Frank Cady as the couple living above the Thorwalds, with their dog

- Jesslyn Fax as "Miss Hearing Aid"[6]

- Rand Harper and Havis Davenport as newlyweds[6]

- Irene Winston as Mrs. Anna Thorwald[6]

Uncredited

- Harry Landers as young man guest of Miss Lonelyhearts[6]

- Ralph Smiles as Carl, the waiter[6]

- Fred Graham as detective[6]

- Eddie Parker as detective[6]

- Anthony Warde as detective[6]

- Kathryn Grant as Girl at Songwriter's Party[6]

- Marla English as Girl at Songwriter's Party[6]

- Bess Flowers as Girl at Songwriter's Party Guest with Poodle[6]

- Benny Bartlett as Stanley, Miss Torso returning boyfriend[6]

- Dick Simmons as Man with Miss Torso[6]

Cast notes

- Director Alfred Hitchcock makes his traditional cameo appearance in the songwriter's apartment, where he is seen winding a clock.[6]

Production

The film was shot entirely at Paramount Studios, which included an enormous indoor set to replicate a Greenwich Village courtyard. Set designers Hal Pereira and Joseph MacMillan Johnson spent six weeks building the extremely detailed and complex set, which ended up being the largest of its kind at Paramount. One of the unique features of the set was its massive drainage system, constructed to accommodate the rain sequence in the film. They also built the set around a highly nuanced lighting system which was able to create natural-looking lighting effects for both the day and night scenes. Though the address given in the film is 125 W. Ninth Street in New York's Greenwich Village, the set was actually based on a real courtyard located at 125 Christopher Street.[7]

In addition to the meticulous care and detail put into the set, careful attention was also given to sound, including the use of natural sounds and music that would drift across the courtyard and into Jefferies' apartment. At one point, the voice of Bing Crosby can be heard singing "To See You Is to Love You", originally from the 1952 Paramount film Road to Bali. Also heard on the soundtrack are versions of songs popularized earlier in the decade by Nat King Cole ("Mona Lisa", 1950) and Dean Martin ("That's Amore", 1952), along with segments from Leonard Bernstein's score for Jerome Robbins' ballet Fancy Free (1944), Richard Rodgers' song "Lover" (1932), and "M'appari tutt'amor" from Friedrich von Flotow's opera Martha (1844), most borrowed from Paramount's music publisher, Famous Music.

Hitchcock used costume designer Edith Head on all of his Paramount films.

Although veteran Hollywood composer Franz Waxman is credited with the score for the film, his contributions were limited to the opening and closing titles and the piano tune ("Lisa") written by one of the neighbors, a composer (Ross Bagdasarian), during the film. This was Waxman's final score for Hitchcock. The director used primarily "diegetic" sounds—sounds arising from the normal life of the characters—throughout the film.[8]

Reception

A "benefit world premiere" for the film, with United Nations officials and "prominent members of the social and entertainment worlds"[9] in attendance, was held on August 4, 1954, at the Rivoli Theatre in New York City, with proceeds going to the American–Korean Foundation (an aid organization founded soon after the end of the Korean War[10] and headed by Milton S. Eisenhower, brother of President Eisenhower).

The movie had a wide release on September 1, 1954.

The movie went on to earn an estimated $5.3 million at the North American box office in 1954.[11]

The film received overwhelmingly positive reviews from critics and is considered one of Hitchcock's finest films. The review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes reports an approval rating of 99% based on 70 reviews, with an average rating of 9.16/10. The critics' consensus states that "Hitchcock exerted full potential of suspense in this masterpiece."[3] At Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 100 out of 100 based on 18 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[12]

Critic Bosley Crowther of The New York Times attended the benefit premiere, and in his review called the film a "tense and exciting exercise"[9] and Hitchcock a director whose work has a "maximum of build-up to the punch, a maximum of carefully tricked deception and incidents to divert and amuse." Crowther also notes: "Mr. Hitchcock's film is not 'significant.' What it has to say about people and human nature is superficial and glib, but it does expose many facets of the loneliness of city life, and it tacitly demonstrates the impulse of morbid curiosity. The purpose of it is sensation, and that it generally provides in the colorfulness of its detail and in the flood of menace toward the end."[9]

Time called it "just possibly the second-most entertaining picture (after The 39 Steps) ever made by Alfred Hitchcock" and a film in which there is "never an instant ... when Director Hitchcock is not in minute and masterly control of his material."[13] The same review did note "occasional studied lapses of taste and, more important, the eerie sense a Hitchcock audience has of reacting in a manner so carefully foreseen as to seem practically foreordained."[13] Variety called the film "one of Alfred Hitchcock's better thrillers" which "combines technical and artistic skills in a manner that makes this an unusually good piece of murder mystery entertainment."[14]

Nearly 30 years after the film's initial release, Roger Ebert reviewed the Universal re-release in October 1983, after Hitchcock's estate was settled. He said the film "develops such a clean, uncluttered line from beginning to end that we're drawn through it (and into it) effortlessly. The experience is not so much like watching a movie, as like ... well, like spying on your neighbors. Hitchcock traps us right from the first ... And because Hitchcock makes us accomplices in Stewart's voyeurism, we're along for the ride. When an enraged man comes bursting through the door to kill Stewart, we can't detach ourselves, because we looked too, and so we share the guilt and in a way we deserve what's coming to him."[15]

Awards and honors

| Date of ceremony | Award | Category | Subject | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| August 22 to September 7, 1954 | Venice Film Festival | Golden Lion | Alfred Hitchcock | Nominated |

| December 20, 1954 | National Board of Review Awards | Best Actress | Grace Kelly | Won |

| January 1955 | NYFCC Awards | Best Actress | Grace Kelly | Won |

| Best Director | Alfred Hitchcock | 2nd place | ||

| February 13, 1955 | DGA Award | Outstanding Achievement in Feature Film | Alfred Hitchcock | Nominated |

| February 28, 1955 | Writers Guild of America Awards | Best Written American Drama | John Michael Hayes | Nominated |

| March 10, 1955 | BAFTA Award | Best Film | Rear Window | Nominated |

| March 30, 1955 | Academy Awards | Best Director | Alfred Hitchcock | Nominated |

| Best Adapted Screenplay | John Michael Hayes | Nominated | ||

| Best Cinematography – Color | Robert Burks | Nominated | ||

| Best Sound – Recording | Loren L. Ryder | Nominated | ||

| April 21, 1955 | Edgar Allan Poe Awards | Best Motion Picture Screenplay | John Michael Hayes | Won |

| November 18, 1997 | National Film Preservation Board | National Film Registry | Rear Window | Won |

| 2002 | Online Film & Television Association Award | OFTA Film Hall of Fame – Motion Picture | Rear Window | Won |

Analysis

In Laura Mulvey's essay "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema," she identifies what she sees as voyeurism and scopophilia in Hitchcock's movies, with Rear Window used as an example of how she sees cinema as incorporating the patriarchy into the way that pleasure is constructed and signaled to the audience. Additionally, she sees the "male gaze" as especially evident in Rear Window in characters such as the dancer "Miss Torso;" she is both a spectacle for Jeff to enjoy, as well as for the audience (through his substitution).[16]

In his book, Alfred Hitchcock's "Rear Window", John Belton further addresses the underlying issues of voyeurism which he asserts are evident in the film. He says "Rear Window's story is 'about' spectacle; it explores the fascination with looking and the attraction of that which is being looked at."[17]

In his 1954 review of the film, François Truffaut suggested "this parable: The courtyard is the world, the reporter/photographer is the filmmaker, the binoculars stand for the camera and its lenses."[18]

Voyeurism

John Fawell notes in Dennis Perry's book, Hitchcock and Poe: The Legacy of Delight and Terror, that Hitchcock "recognized that the darkest aspect of voyeurism . . . is our desire for awful things to happen to people . . . to make ourselves feel better, and to relieve ourselves of the burden of examining our own lives."[19] Hitchcock challenges the audience, forcing them to peer through his rear window and become exposed to, as Donald Spoto calls it in his 1976 book The Art of Alfred Hitchcock: Fifty Years of His Motion Pictures, the "social contagion" of acting as voyeur.[20]

In an explicit example of a condemnation of voyeurism, Stella expresses her outrage at Jeffries' voyeuristic habits, saying, "In the old days, they'd put your eyes out with a red hot poker" and "What people ought to do is get outside and look in for a change."

One climactic scene in the film portrays both the positive and negative effects of voyeurism. Driven by curiosity and incessant watching, with Jeff watching from his window, Lisa sneaks into Thorwald's second-floor apartment, looking for clues, and is apprehended by him. Jeff is in obvious anxiety and is overcome with panic as he sees Thorwald walk into the apartment and notice the irregular placement of the purse on the bed. Jeff anxiously jitters in his wheelchair, and grabs his telephoto camera to watch the situation unfold, eventually calling the police because Miss Lonelyhearts is contemplating suicide in the neighboring apartment. Chillingly, Jeff watches Lisa in Thorwald's apartment rather than keeping an eye on the woman about to commit suicide. Thorwald turns off the lights, shutting off Jeff's sole means of communication with and protection of Lisa; Jeff still pays attention to the pitch-black apartment instead of Miss Lonelyhearts. The tension Jeff feels is unbearable and acutely distressing as he realizes that he is responsible for Lisa now that he cannot see her. The police go to the Thorwald apartment, the lights flicker on, and any danger coming toward Lisa is temporarily dismissed. Although Lisa is taken to jail, Jeff is utterly mesmerized by her dauntless actions.

With further analysis, Jeff's positive evolution understandably would be impossible without voyeurism—or as Robin Wood puts it in his 1989 book Hitchcock's Films Revisited, "the indulging of morbid curiosity and the consequences of that indulgence."[21]

Legacy

Ownership of the copyright in Woolrich's original story was eventually litigated before the Supreme Court of the United States in Stewart v. Abend.[22] The film was copyrighted in 1954 by Patron Inc., a production company set up by Hitchcock and Stewart. As a result, Stewart and Hitchcock's estate became involved in the Supreme Court case, and Sheldon Abend became a producer of the 1998 remake of Rear Window.

Rear Window is one of several of Hitchcock's films originally released by Paramount Pictures, for which Hitchcock retained the copyright, and which was later acquired by Universal Studios in 1983 from Hitchcock's estate.

In 1997, Rear Window was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant". By this time, the film interested other directors with its theme of voyeurism, and other reworkings of the film soon followed, which included Brian De Palma's 1984 film Body Double and Phillip Noyce's 1993 film Sliver.

Rear Window was restored by the team of Robert A. Harris and James C. Katz for its 1999 limited theatrical re-release (using Technicolor dye-transfer prints for the first time in this title's history) and the Collector's Edition DVD release in 2000.

American Film Institute included the film as number 42 in AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies, number 14 in AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills, number 48 in AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) and number three in AFI's 10 Top 10 (Mysteries).[23]

Rear Window was remade as a TV movie of the same name in 1998, with an updated storyline in which the lead character is paralyzed and lives in a high-tech home filled with assistive technology. Actor Christopher Reeve, himself paralyzed as a result of a 1995 horse-riding accident, was cast in the lead role. The telefilm also starred Daryl Hannah, Robert Forster, Ruben Santiago-Hudson, and Anne Twomey. It aired November 22, 1998, on the ABC television network.

Disturbia (2007) is a modern-day retelling, with the protagonist (Shia LaBeouf) under house arrest instead of laid up with a broken leg, and who believes that his neighbor is a serial killer rather than having committed a single murder. On September 5, 2008, the Sheldon Abend Trust sued Steven Spielberg, DreamWorks, Viacom, and Universal Studios, alleging that the producers of Disturbia violated the copyright to the original Woolrich story owned by Abend.[24][25] On September 21, 2010, the U.S. District Court in Abend v. Spielberg, 748 F.Supp.2d 200 (S.D.N.Y. 2010), ruled that Disturbia did not infringe the original Woolrich story.[26]

Home media

On September 4, 2012, Universal Studios Home Entertainment re-released Rear Window on DVD, as a region 1 widescreen DVD. This release includes the items available in the 2001 release.

On May 6, 2014, Universal Studios Home Entertainment released Rear Window to Blu-ray format, with slightly expanded extras.

See also

References

Notes

- Rear Window (Box office/business) on IMDb

- "Rear Window (1954) – Box Office Mojo". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved April 12, 2012.

- "Rear Window (1954)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved August 13, 2019.

- "Complete National Film Registry Listing". Library of Congress. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- "New to the National Film Registry (December 1997) - Library of Congress Information Bulletin". www.loc.gov. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- Rear Window at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Lumenick, Lou (August 7, 2014). "Inside the real Greenwich Village apartment that inspired Rear Window". New York Post. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- DVD documentary

- Crowther Bosley (August 5, 1954) "A 'Rear Window' View Seen at the Rivoli", The New York Times

- Statement by the President on the fund-raising campaign of the American–Korean Foundation from a University of California, Santa Barbara website

- 'The Top Box-Office Hits of 1954', Variety Weekly, January 5, 1955

- "Rear Window Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved June 10, 2019.

- The New Pictures, an August 2, 1954 review from Time magazine

- Review of Rear Window, a July 14, 1954 article from Variety magazine

- 1983 Review of Rear Window re-release by Roger Ebert

- Mulvey, Laura. "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema," '"Screen Vol. 16, No. 3, 1975: 6-18.

- Belton, John (2002). "Introduction: Spectacle and Narrative". In Belton, John (ed.). Alfred Hitchcock's 'Rear Window'. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-521-56423-6. OCLC 40675056.

- Truffaut, François (2014). The Films in My Life. New York, NY: Diversion Books. p. 123. ISBN 978-1-62681-396-0.

- Perry, Dennis (2003). Hitchcock and Poe: the Legacy of Delight and Terror. Maryland: The Scarecrow Press, Inc. pp. 135–153. ISBN 978-0-8108-4822-1.

- Spoto, Donald (1976). The Art of Alfred Hitchcock: Fifty Years of His Motion Pictures. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday & Company, Inc. pp. 237–249. ISBN 978-0-385-41813-3.

- Wood, Robin (1989). Hitchcock's Films Revisited. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 100–107. ISBN 978-0-231-12695-3.

- Stewart v. Abend, 495 U.S. 207 (1990).

- "AFI's 10 Top 10". American Film Institute. 2016. Retrieved August 23, 2016.

- Edith Honan (September 8, 2008). "Spielberg ripped off Hitchcock Classic". Reuters. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- Chad Bray (September 9, 2008). "2nd UPDATE: Trust Files Copyright Lawsuit Over Disturbia". CNN Money. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- "Rear Window copyright claim rejected". BBC News. September 22, 2010.

Further reading

- Orpen, Valerie (2003). "Continuity Editing in Hollywood". Film Editing: The Art of the Expressive. Wallflower Press. pp. 18–43. ISBN 978-1-903364-53-6. OCLC 51068299.

- Orpen treats Hitchcock's and Tomasini's editing of Rear Window at length in a chapter of her monograph.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rear Window. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Rear Window |

- John Belton (ndg) "Rear Window" at National Film Registry

- Rear Window at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Rear Window on IMDb

- Rear Window at the TCM Movie Database

- Rear Window at AllMovie

- Rear Window at Rotten Tomatoes

- Rear Window at Box Office Mojo

- Detailed review at Filmsite.org

- Rear Window essay by Daniel Eagan in America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry, A&C Black, 2010 ISBN 0826429777, pages 490-491