Via Giulia

Via Giulia is a street in Rome, Italy, that is of historical and architectural importance.

Arco Farnese across Via Giulia | |

| Length | 950 m (3,120 ft) |

|---|---|

| Location | Rome |

| Quarter | Regola, Ponte |

| From | Piazza San Vincenzo Pallotti |

| To | Piazza dell'Oro |

| Construction | |

| Completion | 1512 |

| Other | |

| Designer | Donato Bramante |

The road, committed by Pope Julius II to Donato Bramante, was one of the first important urban planning projects in papal Rome, and its opening had three aims: the creation of a major roadway inserted in a new system of streets superimposed on the maze of alleys of medieval Rome; the construction of a large avenue surrounded by sumptuous buildings to testify to the renewed grandeur of the Catholic Church; and finally, the foundation of a new administrative and banking centre near the Vatican, the seat of the popes, and far from the traditional city centre on the Capitoline Hill, dominated by the Roman baronial families opposed to the pontiffs.

Despite the interruption of the project due to the pax romana of 1511 and the death of the pope two years later, the new road immediately became one of the main centres of the Renaissance in Rome. Many palaces and churches were built by the most important architects of the time, such as Raffaello Sanzio and Antonio da Sangallo the Younger, who often chose to move into the street. They were joined by several noble families, while European nations and Italian city-states chose to build their churches in the street or in the immediate vicinity.

In the Baroque period the building activity, directed by the most important architects of the time such as Francesco Borromini, Carlo Maderno and Giacomo della Porta, continued unabated, while the street, favorite location of the Roman nobles, became the theatre of tournaments, parties and carnival parades. During this period the popes and private patrons continued to take care of the road by founding charitable institutions and providing the area with drinking water.

From the middle of the 18th century, the shift of the city centre towards the Campo Marzio caused the stop of building activity and the abandonment of the road by the nobles. These were replaced by an artisan population with its workshops, and Via Giulia took on the solitary and solemn aspect that would have characterized it for two centuries. During the Fascist period some construction projects broke the unity of the road in its central section, and the damage has not yet been repaired. Despite this, Via Giulia remains one of Rome's richest roads in art and history, and after a two-century decline, from the 1950s onwards the road's fame was renewed to be one of the city's most prestigious locations.

Location

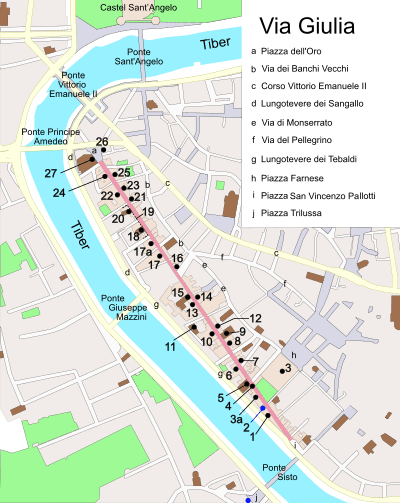

Via Giulia runs along the left (east) bank of the Tiber from Piazza San Vincenzo Pallotti, near Ponte Sisto, to Piazza dell'Oro.[1] It is about 1 kilometre long and connects the Regola and Ponte Rioni.[1]

Denominations

The road was named after its patron, Pope Julius II della Rovere (r. 1503-1513), who ordered its construction in 1508.[2][1] It had been also called Via Magistralis (lit. "master road") because of its importance, [1] and Via Recta (lit. "straight road") because of its layout.[3]

History

The area of the ancient Campus Martius developed into one of the most densely populated districts (abitato) of Rome since the early Middle Ages. The maze of narrow alleys was criss-crossed by three narrow thoroughfares: the Via Papalis (lit. "papal road"),[lower-alpha 1] the Via Peregrinorum (lit. "pilgrims' road") [lower-alpha 2] and the Via Recta (lit. "straight road", a name common to many roads in medieval Rome).[lower-alpha 3][4] Processions travelled through these streets almost daily during the Middle Ages to the Angels' Bridge. As Dante Alighieri described in the Divine Comedy,[lower-alpha 4] in 1300, Pope Boniface VIII (r. 1294-1303) ordered a two-way traffic system to be set up to avoid traffic jams or panic as a response to the dense crowds on Angels' Bridge.[5] After Pope Martin V (r. 1417-1431) returned to Rome in 1420, the influx of pilgrims increased significantly again, especially in the Jubilee years. On 29 December 1450, the last day of the Holy Year, a stampede broke out on the bridge that killed more than 300 people.[5][6] As a result of the catastrophe, Pope Nicholas V (r. 1447-1455) ordered the Angels' Bridge to be cleared of stalls and shops and the first urban planning measures in the area were initiated. In 1475, Pope Sixtus IV (r. 1471-1484) ordered the Ponte Sisto, named after him, to be built across the Tiber (inscription) in order to relieve the pilgrimage route across the Angels' Bridge and to connect the rioni of Regola and Trastevere.[7] At the same time he ordered the restoration of Via Pelegrinorum and the area around the Campo de' Fiori (inscription). According to the chronicler Stefano Infessura, however, strategic reasons aside from reducing traffic were also important for these projects.[8] In 1497 Pope Alexander VI (r. 1492-1503) ordered the widening of Via Peregrinorum [lower-alpha 5] (Fig.) and the restoration of Via della Lungara on the right bank of the Tiber from Ponte Sisto to St. Peter's Basilica.

The project of Pope Julius II

In addition to reconstructing St. Peter's Basilica, Julius II implemented multiple projects in the framework of Rome's urban renewal (Renovatio Romae) in the Ponte, Parione, Sant'Eustachio and Colonna rioni, a task which was started forty years before by his uncle, Pope Sixtus IV (r. 1471-1484).[9] One of the most important projects was the creation of two new straight streets on the left and right banks of the Tiber: the Via Giulia on the left bank, a new grand avenue through the most densely populated quarter of Rome, from the Ponte Sisto to the Florentine merchant quarter on the Tiber bend,[10] and a straight road along the right bank of the Tiber from the Porta Settimiana in Trastevere to the Hospital of Santo Spirito in the Borgo, the Via della Lungara.[11] Both roads flanked the Tiber and were closely connected to it. [12] The Lungara had the dual aim to relieve the pilgrimage route to Saint Peter[11] and transport goods coming from the Via Aurelia and the via Portuense roads towards the centre of the city. The Pope intended for it to reach Piazza di Santa Maria in Trastevere and the port of Ripa Grande. [12]

The main goal behind these plans was to superimpose a regular road network with the focus given to the Tiber by medieval Rome's disorderly buildings; together with the new Via Alessandrina that Alexander VI opened in the Borgo, the Via dei Pettinari that connected the Trastevere on one side and the Campidoglio on the other, the Lungara and Via Giulia created a quadrilateral network of modern roads in the city's maze of alleys. [12] In the original project Via Giulia was supposed to reach the Hospital of Santo Spirito in Borgo via the rebuilt Pons Neronianus. [1][13] The center of the city shifted towards the Vatican and Trastevere and away from the Palazzo Senatorio on the Capitoline Hill, which was the symbol of the Roman nobility's power; [14][12] the plan was intended to separate the papacy from the city's powerful noble families, particularly the Orsini and Colonna families.[14]

These projects had a secondary, celebrative goal to promote the Pontiff as the unifier of Italy and the renewer of Rome; in 1506, after the end of the plague, the Pope overthrew the powerful Baglioni and Bentivoglio families and conquered Perugia and Bologna,[12] as testified in an inscription along the Via dei Banchi Nuovi.[lower-alpha 6]

Aside from serving as a means of communication and representation for the Church, the road was supposed to host the city's new layman's administrative center. [12] Luitpold Frommel discovered a drawing by Donato Bramante in the Uffizi which showed a new huge administrative complex, the Palazzo dei Tribunali, facing a representative square (the Foro Iulio) that opened along the new street. [12] This forum was thought to lie between the Palazzo and the old Cancelleria (today's Palazzo Sforza-Cesarini). [15] The centre was not far from the Apostolic Camera (the Pope's treasury) in Palazzo Riario and the new Palazzo della Zecca (lit. "papal mint") erected by Bramante at the edge of Via dei Banchi Nuovi (also named Canale di Ponte).[15] By this road lay the merchants' and bankers' houses and offices, like the Altoviti, Ghinucci, Acciaiuoli, Chigi and Fugger.[9] Close economic ties with Tuscan bankers like Agostino Chigi were sought and promoted.[16]

Around 1508 Bramante was asked by the Pope to start expropriating and demolishing properties in the densely populated Campo Marzio to create the new street.[2]

Giorgio Vasari writes:

Si risolvé il Papa di mettere in strada Giulia, da Bramante indrizzata, tutti gli uffici e le ragioni di Roma in un luogo, per la commodità ch’a i negoziatori averia recato nelle faccende, essendo continuamente fino allora state molto scomode.

The Pope decided to consolidate all the offices and financial centers of Rome in one place in the Via Giulia designed by Bramante. This would have made it easier for businessmen to conduct their business, which until then had been a cumbersome process.

However, in 1511, an agreement (known as the Pax Romana) between the feuding Orsini and Colonna families was formed, which caused the Via Giulia and the Palazzo dei Tribunali projects to be suspended.[14] Apart from a few rusticated blocks between the Via del Gonfalone and the Vicolo del Cefalo, nothing remained of the palace. [18]

Via Giulia in the 16th and 17th century

After the death of Julius II in 1513, his successor, Pope Leo X (r. 1513-1521) from the House of Medici, continued the work.[19] Further construction was done mainly in the northern part of the road between the unfinished Palazzo dei Tribunali and the banking district, which supported the Florentine merchant community. [19] In this area, important artists, such as Raphael and Antonio da Sangallo the Younger, acquired plots of land or built palaces. [20][21]

The area south of the church of San Biagio changed radically: the central part of the Via Giulia around Monte dei Planca Incoronati became a slum filled with inns, brothels, and infamous locations like Piazza Padella, a venue known for duels and stabbings up to the end of 19th century and demolished in the 1930s.[22] The area between Via del Gonfalone, Via delle Carceri, Via di Monserrato, and the Tiber was a major district of ill-repute since the Middle Ages; a manuscript from 1556 reports about the quarter around the eventually demolished church of San Niccolò degli Incoronati hosted "... 150 houses of very simple people, whores and dubious persons ...".[23] The quarter starting from the church of Santa Aurea, today Santo Spirito dei Napoletani, was called Castrum Senense in the Middle Ages because it was mainly inhabited by people from Siena.[3] At this end of the Via Giulia, a well-defined architectural development plan was drawn up, which started with building the Farnese residence. In 1586, the Ospizio dei Mendicanti (lit. "Beggar's Hospice") was built by the architect Domenico Fontana on the orders of Pope Sixtus V (r. 1585-1590) and marked the end of the Via Giulia. [24] It was built to solve the begging problem in the city and was given a yearly endowment of 150,000 scudi which could employ 2,000 people.[25]

At the beginning of the 16th century it had become fashionable for the various nations and city-states to have their own churches built in Rome known as the chiese nazionali. [26] The rioni of Regola and Ponte, along the processional and pilgrim roads, were the preferred locations. The Florentines, the Sienese, and the Neapolitans had their churches built in Via Giulia (the San Giovanni, the Santa Caterina, and the Santo Spirito respectively),[27] while the Bolognese (San Giovanni e Petronio), Spanish (Santa Maria in Monserrato), English (San Tommaso di Canterbury) and Swedish (Santa Brigida) churches were built in the Regola rione.[26]

In order to supply the quarter with sufficient drinking water, Pope Paul V (r. 1605-1621) had the Aqua Paola extend over the Tiber. In 1613, the Fontanone di Ponte Sisto (lit. "The Big Fountain of the Sistine Bridge") was built on the façade of the beggars' hospice on Via Giulia. [28] It was demolished in 1879 and rebuilt in 1898 on the opposite side of the Ponte Sisto in what is now Piazza Trilussa.(Fig.). [28]

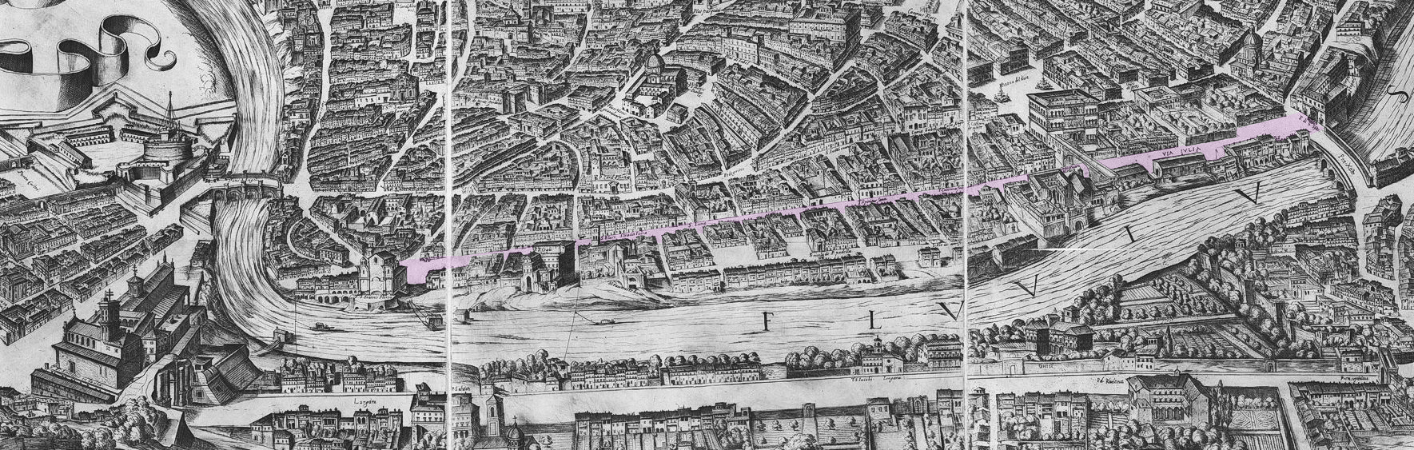

Via Giulia; Particular from Almae urbis Romae prospectus by Antonio Tempesta (1645)

Via Giulia; Particular from Almae urbis Romae prospectus by Antonio Tempesta (1645)

At the end of the 16th century Via Giulia's path was fixed; it ended by the Florentine quarter to the north and the Ospizio dei Mendicanti to the south. It became less of a major commercial street and more a busy promenade and a place for celebrations, processions (such as that of the ammantate, poor girls which were dowried by the goldsmiths of Sant'Eligio degli Orefici) and races.[29][30]

In 1603 Tiberio Ceuli held a tournament at Palazzo Sacchetti,[31] while in 1617 Cardinal Odoardo Farnese organized a Saracen tournament at the Oratorio della Compagnia della Morte, to which he invited eight cardinals.gig118[32] During the summer months the street was sometimes flooded for the pleasure of the common people and the nobility.[30] One of the most glamorous celebrations was held by the Farnese in 1638 to celebrate the birth of the French dauphin, the future king Louis XIV. [30] Via Giulia hosted buffalo races, parades of carnival floats, and in 1663 the organisation of a horse race with naked hunchbacks during Carnival is handed down.[10] During the carnival, Via Giulia hosted several feasts promoted by the Florentines.[30]

On 20th August 1662, Via Giulia was the scene of an episode that had important consequences: a brawl near the Ponte Sisto bridge between soldiers of the Corsican Guard and French soldiers belonging to the retinue of Louis XIV's ambassador Charles III de Créquy resulted in the withdrawal of the ambassador from Rome and the French invasion of Avignon.[33] In order to avoid worse consequences, the pope was forced to humiliate himself, disbanding the Corsican guard and erecting a "pyramid of infamy".[33]

In the baroque period, other important building projects contributed to the later appearance of the street: the church of San Giovanni dei Fiorentini, [27] the Carceri Nuove (lit. "New Prisons"),[34] the Palazzo Falconieri, [35] and the churches of Sant'Anna dei Bresciani and Santa Maria del Suffragio.[36] The street's character changed little despite the addition of these buildings. Via Giulia was rather left out in Rome's general urban development plan.

Development in the 18th and 19th centuries

In the 18th century the Via Giulia remained primarily a place to organise feasts: in 1720 the Sienese held a festival to celebrate the promotion of Marc'Antonio Zondadari to Grand Master of the Order of Malta.[10] Fireworks was set off near the Fontanone di Ponte Sisto; [30] two triumphal arches were raised above the street: one in Santo Spirito and the other near Palazzo Farnese; [10][30] and the Fountain of the Mascherone poured wine for the people instead of water. [30]

Under Pope Clement XI's (r. 1720-1721) rule, the beggars housed in the Ospizio dei Mendicanti were transferred to the San Michele a Ripa.[37] The building was occupied by both poor unmarried girls (zitelle in the Romanesco dialect) and a congregation made up of 100 priests and 20 clerics; the latter prayed for the souls of deceased priests; [37] as such, the building was nicknamed the Ospizio dei cento preti ("Hospice of the Hundred Priests").[37]

In the 19th century only a few new buildings or restoration projects were realised: among them were the youth prison (Palazzo del Gonfalone) (1825-27), the renovation of the Armenian Hospice next to the church of San Biagio (1830), the new façade of the Santo Spirito dei Napoletani (1853), and the Collegio Spagnuolo (1853). However, this did not stop the general decline of the street that started in the middle of the 18th century.[38] The nobility abandoned the palaces on the street to move to the new center of urban life in the Campo Marzio, and in their place the road hosted artisans and became less of a centre for festivities.[39]

Via Giulia since 1870

After Rome became the capital of the Kingdom of Italy in 1870, the Tiber (known for flooding, particularly in Campus Martius) had its banks worked on in 1873 by constructing Lungoteveres, which since 1888 were erected along the road and required the church of Sant'Anna dei Bresciani to be torn down.[40] The Lungoteveres completely cut off Via Giulia from the Tiber and prevented the loggias and gardens of the palaces facing the river, such as the Palazzi Medici-Clarelli, Sacchetti, Varese, and Falconieri from having a view of the river. Significant building demolitions during the fascist period left a large gap between Via della Barchetta and the Vicolo delle Prigioni, which to this day has only been partially filled by the new building of the Liceo Classico Virgilio.[41] The street has regained its status as one of the most prestigious streets in the city.[42][30] Numerous events took place in 2008 during its 500th anniversary; some churches and palaces were restored and opened to visitors.[42]

Landmarks on Via Giulia

Via Giulia extends northwest for about one kilometre from the Piazza San Vincenzo Pallotti on the Ponte Sisto to the Piazza dell'Oro in front of the church of San Giovanni dei Fiorentini. From 1586, the Ospizio dei Mendicanti ("Beggars' Hospice") marked the southern end of the street.[24] Under Paul V's decree in 1613, a fountain that brought the Aqua Paola to the Regola rione was built against its façade (see engraving by Giuseppe Vasi above).[28] This fountain was demolished together with the hospice in 1879 and rebuilt in 1898 on the opposite side of the Ponte Sisto in what is now Piazza Trilussa (Fig.). [28]

1 Palazzina Pateras Pescara (Via Giulia 251)

This last building in Via Giulia was built in 1924 by Marcello Piacentini on behalf of the Avvocato Pateras.[43] Today it houses the Consulate of the French Republic in Rome. [43]

.jpg) 1 Palazzo Pateras Pescara

1 Palazzo Pateras Pescara

2 Fontana del Mascherone

The fountain diagonally opposite Palazzo Farnese was built around 1626 by Carlo Rainaldi and paid for by the Farnese.[44] It was planned in 1570 to be a public fountain fed by the Aqua Virgo aqueduct to supply people with clean drinking water. [44] However, installation was only possible after Paul V ordered the water pipe to be extended over the Ponte Sisto in 1612. [44][45] The fountain consists of an ancient large marble mascaron ("Mascherone") on a background with volutes in marble, crowned by the symbol of the Farnese, a metal Fleur-de-lis. [44] The fountain was moved against the wall in 1903, losing most of its charm.[44] The poet Wilhelm Waiblinger died in 1830 in the house opposite to it. (Fig.).[46]

2 Fontana del Mascherone

2 Fontana del Mascherone

3 Palazzo Farnese (Via Giulia 186)

The garden façade of this palace building is oriented towards the Via Giulia.[44] In 1549 it was designed according to Vignola's drawings and completed by Giacomo della Porta in 1589.[47] The garden between the façade and the Via Giulia was once adorned by the Farnese bull (now in the National Archaeological Museum in Naples) (Fig.). [44] The palace is now the French Embassy in Italy.[48]

3 Palazzo Farnese

3 Palazzo Farnese

3a Camerini Farnesiani (Via Giulia 253-260)

Behind the row of lower buildings ("Camerini Farnesiani") (Fig.), which today belong to the French Embassy, lay a small palace with garden, the Palazzetto Farnese, built around 1603 by Cardinal Odoardo Farnese as his hermitage, [49] also known as Eremo del Cardinale ("Cardinal's hermitage"). This private retreat of the Cardinal, decorated with frescoes by Giovanni Lanfranco, was accessible from Palazzo Farnese via a terrace and the Arco Farnese. [49] The building and garden were destroyed in the Tiber regulation after 1870.

3a Camerini Farnesiani

3a Camerini Farnesiani

4 Arco Farnese

The bridge connects Via Giulia to the Palazzo Farnese. It was erected in 1603,[49] and was used to observe festive processions, games, and horse races in Via Giulia, particularly during Carnival.

4 Arco Farnese

4 Arco Farnese

5 Santa Maria dell'Orazione e Morte

The church, built in 1575-76, is located in the immediate vicinity of Palazzo Farnese and belonged to the Compagnia della Morte ("Death's Brotherhood") founded in 1538.[50] The fraternity was tasked with burying the dead that were recovered from the river or found in the area surrounding Rome. The building was demolished in 1733 and rebuilt by Ferdinando Fuga in 1737.[51] Its cemetery on the banks of the Tiber was demolished when the river was regulated in 1886. [50]

5 Santa Maria dell'Orazione e Morte

5 Santa Maria dell'Orazione e Morte

6 Palazzo Falconieri also Palazzo Odescalchi Falconieri (Via Giulia 1)

The original building was built in the 16th century for the Roman noble family of the Ceci and directly adjoins the church of Santa Maria dell'Orazione e Morte.[52] It was sold by the Ceci in 1574 to the Odescalchi family before being passed to the Farnese in 1606.[52] Eventually the Florentine nobleman Orazio Falconieri bought it in 1638 for 16,000 scudi.[35] From 1646 to 1649 he commissioned the architect Francesco Borromini to extend the palace. [35] The sides of the façade on Via Giulia are decorated with two pilasters in the shape of large hermas with female breasts and falcon heads.[53] The façade on the Tiber side features a three-arched loggia [53] dating back to 1646. From 1814 Cardinal Joseph Fesch, uncle of Napoleon Bonaparte lived there, and from 1815 to 1818 he hosted his stepsister Laetitia Ramolino, the emperor's mother. [53] In 1927 the Kingdom of Italy ceded the palace to the Hungarian State, which established it as the seat of the Hungarian Academy (Accademia d'ungheria).[53] Today, in addition to the Academy, the palace is home to the Pontificium Institutum Ecclesiasticum Hungaricum in Urbe.[54]

- 6 Palazzo Falconieri

7 Palazzo Baldoca-Muccioli (Via Giulia 167)

The history of the palace is closely linked to the neighbouring Palazzo Cisterna. [55] Both properties were acquired by the sculptor Guglielmo della Porta. [55] Guglielmo began to work around 1546 in the service of Pope Paul III (r. 1534-1549) who at the death of Sebastiano del Piombo entrusted him with the lucrative office of Keeper of the Seals (Italian: Custode del Piombo).[56] The sculptor gave the building to the Baldoca family and then to the Muccioli. At the beginning of the 20th century the palace served as the residence of the English ambassador in Rome, Lord Rennel of Rodd, who bought and had it restored in 1928. [55]

7 Palazzo Baldoca Muccioli

7 Palazzo Baldoca Muccioli

8 Palazzo Cisterna (Via Giulia 163)

The Palazzo Cisterna was built by Guglielmo della Porta and served as his residence. [55] Above the architrave of the windows on the first floor the inscription FRANCISCVS TANCREDA ET GVILELMVS D(ella) P(orta) ME(ediolanensis) - S(culptor) CI(vis) RO(manus) can be read (Fig.). [55] From a letter to a friend, it appears that the palace was completed in 1575. In 1600 Spanish missionaries acquired the palace and sold it to the Cisterna family at the beginning of the 20th century. [55] It was partially sold to the Ducci family in the second half of the 20th century.[57]

.jpg) 8 Palazzo Cisterna

8 Palazzo Cisterna

9 Santa Caterina da Siena in Via Giulia

The history of this church is closely linked to the Sienese Brotherhood.[58] A community of merchants, bankers and craftsmen from Siena had been living in what was to be Via Giulia, where at that time stood the castrum Senense since the 14th century. [58] In 1519 the Brotherhood was canonically erected by Leo X. [58] In 1526 they commissioned Baldassare Peruzzi to build the church in honour of their saints, an oratory, and a house for the clerics. [58] The funds were provided by the Sienese nobility in Rome, particularly by Cardinal Giovanni Piccolomini and the banker Agostino Chigi. Since it was in a dilapidated state, it was rebuilt between 1766 and 1768 according to Paolo Posi's designs,[59] while the interior decor was completed in 1775. [59] The Archconfraternity of the Sienese still owns the building today.[55] During Via Giulia's 500th anniversary of the street in 2008 the altarpiece by Girolamo Genga has been restored.[60]

- 9 Santa Caterina da Siena

10 Palazzo Varese (Via Giulia 14-21)

The palace opposite Santa Caterina da Siena was built between 1617 and 1618 by Carlo Maderno on behalf of Monsignor Diomede Varese.[61] In 1788 Monsignor Giuseppe degli Atti Varese gave the building to the Congregation Propaganda Fide when his family line died out. [61] After exchanging owners several times the palace finally came into the possession of the Mancini family.[58] The front consists of two upper floors and a mezzanine. On the ground floor is the main portal and above it is a balcony on consoles, flanked by three windows each. A portal opens into the yard with three arcades stacked on one another (Fig.). The yard originally opened to a garden by the river.

.jpg) 10 Palazzo Varese

10 Palazzo Varese

11 Sant'Eligio degli Orefici (Via di Sant'Eligio 9)

The small church is off the Via Giulia and serves as the guild church of the Roman gold- and silversmiths.[62] Its construction is attributed to Raphael, although it is possible that after the death of the artist it was finished by Baldassare Peruzzi.[63]

11 Sant’Eligio

11 Sant’Eligio

12 Palazzo del Collegio Spagnolo (Via Giulia 151)

The Palacio de Monserrat by Antonio Sarti and Pietro Camporese was built in 1862 by the will of Queen of Spain Isabella II and is the Spanish High Centre for Ecclesiastical Studies today.[58][64] The Centre is attached to the Spanish National Church of Santa Maria di Monserrato on Via di Monserrato behind it.[64] Construction on Via Giulia stopped with the completion of this building complex in the 19th century.

12 Collegio Spagnolo

12 Collegio Spagnolo

13 Liceo Statale Virgilio (Via Giulia No 35 ff.)

One of the most important state school complexes in Rome was built between 1936 and 1939 [65] by Marcello Piacentini. The building complex between Via Giulia and the Lungotevere dei Tebaldi includes the façade of the Collegio Ghislieri (Fig.), designed by Carlo Maderno (16th century),[66] and the church of the Santo Spirito dei Napoletani.

14 Palazzo Ricci (Via Giulia 146)

(Fig.) The present building was originally a cluster of unconnected buildings, built at different times, opposite the Collegio Ghislieri.[67] The building complex was merged in 1634 and 1683. The main façade facing Piazza de'Ricci shows strongly faded remains of a graffito by Polidoro da Caravaggio (16th century). On the side facing Via Giulia, a continuous façade gave the complex its present uniform appearance (Fig.).

14 Palazzo Ricci

14 Palazzo Ricci

15 Santo Spirito dei Napoletani

In the Pius V church catalogue this church is listed under the name of Santa Aura in strada Iulia.[68] It was dedicated to Saint Aurea, the patron saint of Ostia.[68] A nunnery was attached to the church.[68] In 1439 the church was restored at the expense of Cardinal Guillaume d'Estouteville. [68] In 1572 Cardinal Inigo d'Avalos founded in the dilapidated building the Confraternita dello Spirito Santo dei Napoletani ("Brotherhood of the Holy Spirit of the Neapolitans"), who bought it from the nuns in 1574.[69] Between 1619 and 1650 a new building was erected, with a project of Ottavio Mascherino and a façade by Cosimo Fanzago. [69] It was dedicated to the Holy Spirit. [69] In the following centuries it was renovated several times, at the beginning of the 18th century by Carlo Fontana [69] and in the middle of the 19th century the façade was renovated by Antonio Cipolla (1853).[70] It was the National Church of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. The last King of Naples Francis II and his wife Marie Sophie Amalie, Duchess in Bavaria, were buried in the church in 1942. [70][71] After a long period of restoration, the church is open to the public again since 1986. (Fig.)

15 Santo Spirito dei Napoletani

15 Santo Spirito dei Napoletani

16 San Filippo Neri in Via Giulia

Construction of the small church opposite the Carceri Nuove was sponsored by Rutilio Brandi, a glove-maker from Florence, and given to the Compagnia delle santissime piaghe around 1600. The church was originally dedicated to Saint Trophimus.[72] It was connected to a residence for unmarried girls (zitelle) and a hospital for sick priests.[73] Since the residence was dedicated to San Filippo Neri, after some years the church too changed its dedication to him.[74] In 1728 Filippo Raguzzini restored the church on behalf of Pope Benedict XIII (r. 1724-1730). [73] The church barely escaped destruction in the early 1940s due to the construction of a large road that should have joined Ponte Mazzini and the Chiesa Nuova. [73] This road was never built due to the World War II. [73] It was abandoned after the war before being restored in 2000 for non-religious purposes.[75]

16 San Filippo Neri

16 San Filippo Neri

17 Carceri Nuove (Via Giulia 52)

Since 1430 the Savelli family had a monopoly on prisons in the city, especially Corte Savella at 42 Via di Monserrato. The inhumane penal system in the Corte Savella caused Pope Innocent X (r. 1644-1655)) to withdraw the Savelli's monopoly on the penal system in Rome. As a sign of new Justitia Papalis, he had the new penal institution, the Carceri Nuove, built in Via Giulia.[34] This new prison was built between 1652 and 1655 by the architect Antonio del Grande.[34][lower-alpha 7] The Carceri Nuove were considered a model of a humane penitentiary system in their time. The building and its purpose had a rather negative influence on the image of the magnificent street, which led to the suspension of construction in the following years and the Renaissance character of the street being preserved.[30] The building acted as a prison until the opening of Regina Coeli in Trastevere [76] in 1883, further on until 1931 as a youth prison. [76] From 1931 the palace housed the headquarters of the Centro di Studi Penitenziari ("Research Institute for Criminal Justice") and a specialized library. [76] Today the building houses the Direzione Nazionale Antimafia e Antiterrorismo ("National Directorate for Anti-Mafia and Anti-Terrorism").[77]

17 Carceri Nuove

17 Carceri Nuove

17a Palazzo del Gonfalone

The building between the Vicolo della Scimia and Via del Gonfalone has no entrance from Via Giulia. [78] It was built between 1825 and 1827 under Pope Leo XII (r. 1823-1829) according to plans by Giuseppe Valadier as a prison for the youth.[78] Today the building houses the Museo Criminologico (lit. "Criminological Museum").[79]

17a Palazzo del Gonfalone

17a Palazzo del Gonfalone

18 Santa Maria del Suffragio

In 1592 the Confraternita del Suffragio ("Brotherhood of Intercession") was founded next to the church of San Biagio della Pagnotta to implore the intercession for the souls of the purgatory. [36] The Brotherhood was approved by Pope Clement VIII (r. 1592-1605) in 1594 [36] and was elevated to the status of Arciconfaternita ("Archbishopric Brotherhood") by Paul V in 1620. Thanks to several donations, in 1662 the erection of the church began as a project of architect Carlo Rainaldi. [36] The building was consecrated in 1669, and the façade was finished in 1680. [36] The church's interior was renovated in 1869; the frescoes inside the church are by Cesare Mariani (Coronation of the Virgin) and Giuseppe Chiari (Nativity of Mary and Adoration of the Magi).[80]

18 Santa Maria del Suffragio

18 Santa Maria del Suffragio

19 Palazzo dei Tribunali

Julius II's most important planned project in the new street was a central administration building, in which a large part of the city's important offices and courts ("tribunali") were to be grouped together. [81] The Pope's commission to Donato Bramante (at the time main architect of the new St. Peter's Basilica) [81] was issued around 1506, and construction in the area between Vicolo del Cefalo and Via del Gonfalone began before 1508, [81] but was interrupted as in 1511 by the Pax Romana. [14] With the Julius II's death in 1513, construction completely stopped. Giorgio Vasari wrote: [17]

Onde Bramante diede principio al palazzo ch'a San Biagio su 'l Tevere si vede, nel quale è ancora un tempio corinzio non finito, cosa molto rara, et il resto del principio di opera rustica bellissimo che è stato gran danno che una sì onorata et utile e magnifica opra non si sia finita, ché da quelli della professione è tenuto il più bello ordine che si sia visto mai in quel genere.

Bramante therefore began the construction of the palace, which can be seen near San Biagio on the Tiber. In it there is still an unfinished Corinthian temple, something very rare and the remains of the beginning in beautiful Opera Rustica. It is a great pity that such an important, useful and great project has remained unfinished. Experts considered it to be the most beautiful building of its kind ever seen.

Some remains of the mighty rusticated walls, called i sofà di Via Giulia (English: Via Giulia's couches) by the Roman population, between Via del Gonfalone and Vicolo del Cefalo along Via Giulia, can be seen today. [18]

_1.jpg) 19 Sofà

19 Sofà

20 San Biagio della Pagnotta (San Biagio degli Armeni)

This church was dedicated to Saint Blaise of Sebaste and is mentioned in the church catalogues of the Middle Ages under the name of San Biagio de Cantu Secuta.[18] The name "della pagnotta" is derived from the Roman word pagnotta ("bread roll"), which was distributed to the faithful on the 3 February (feast of St. Blaise) and thought to protect against throat illnesses.[82] The church was attached to one of the first abbeys in Rome. [18] An inscription on the interior commemorates the construction of the church by an abbot Dominicus in 1072.[83] According to the Bramante's plans, this church was to be included in the construction of the Palazzo dei Tribunali. From 1539 to 1835 it was a parish church. [82] In 1826 Pope Gregory XVI (r. 1831-1846) assigned the church to the Armenian community of Santa Maria Egiziaca. [82] Since then it has been called officially San Biagio degli Armeni. [18]

20 San Biagio della Pagnotta

20 San Biagio della Pagnotta

21 Palazzo Ricci-Donarelli (Via Giulia no. 99-105)

The palace is opposite to the Palazzo Sacchetti and was originally a group of residential buildings that first belonged to the Ricci and later to the Donarelli family.[84] The complex was restructured in 1663, possibly by Carlo Rainaldi.[81]

22 Palazzo Sacchetti (Via Giulia 66)

Antonio da Sangallo the Younger built the palace on land bought in 1542 by the Vatican Chapter.[20] The façade still bears the chipped coat of arms of Paul III.[20] His son Orazio inherited the building and sold it in 1552 to Cardinal Giovanni Ricci di Montepulciano, who had the palace extended to its current dimensions by the architect Nanni di Baccio Bigio.[20] An inscription[lower-alpha 8] in the Vicolo del Cefalo's side wall states that the palace was exempted from paying the census tax in 1555.(Fig.) [85] The building changed hands several times.[86] In 1649 it was bought by the Florentine Sacchetti family, whose name it still bears.[86] The entrance to Via Giulia is made of marble and flanked on both sides by three large windows with grilles, thresholds, and cornices.[87] In the left corner of the palace there is a small fountain (Fig.) flanked by caryatides with two dolphins embedded in the wall; [87] this refers to the later owners, the Ceuli family, whose coat of arms was chipped. [87] Notable features inside include the Salone dei Mappamondi ("Hall of World Maps"), designed by Francesco Salviati,[85] and the dining room with two frescoes designed by Pietro da Cortona. [85] The writer Ingeborg Bachmann lived in this palazzo in 1973 dying at Sant'Eugenio Hospital on 17 October 1973.[88]

.jpg) 22 Palazzo Sacchetti

22 Palazzo Sacchetti

23 Palace with the Farnese coats of arms (Via Giulia 93)

The building's first owner could have been Durante Duranti, lover of Costanza Farnese, or Guglielmo della Porta, which in this case would have been also the architect. [84] The palazzo takes its name from the three coats of arms of the Farnese family, which were added to the façade under Paul III. [84] In the centre of the upper floor there is the coat of arms of Paul III with the papal tiara and the keys between two unicorns. [84] On the left is the coat of arms of Cardinal Alessandro Farnese and on the right the coat of arms of his brother Ottavio Farnese or of Pierluigi Farnese, both Dukes of Parma and Piacenza. [84]

%3BPalast_mit_den_Farnese_Wappen.jpg) 23 Palazzo with the Farnese coats of arms

23 Palazzo with the Farnese coats of arms

24 Palazzo Medici Clarelli (Via Giulia 79)

Antonio da Sangallo the Younger built this palace as a private residence around 1535-1536.[89] After Sangallo's death in 1546 the building was owned by the Florentine Migliore Cresci. [89] An inscription above the main portal (Fig.) immortalizes Duke Cosimo I de' Medici. [89] The palace for some time belonged to the Tuscan Consulate in Rome. [89] At the end of the 17th century it was acquired by the Marini Clarelli family.[90] In the 19th century it was used as barracks before being sold to the city of Rome in 1870.[90] The façade (richly historiated at the time of Cresci) and the portal are lined with rusticated ashlars.[21] On the sides of the portal there are badly rebuilt large windows on consoles. [21]

24 Palazzo Medici Clarelli

24 Palazzo Medici Clarelli

25 Casa di Raffaello (Via Giulia 85)

This palace, erroneously called the House of Raphael, was built after 1525 for the Vatican Chapter according to a design by the architect Bartolomeo de Ramponibus.[21] Raphael originally acquired several plots of land here. [21] However, he died before the building's construction began. The designs were created by Raphael and Antonio da Sangallo the Younger. An inscription above the windows of the first floor is dedicated to Raphael: POSSEDEVA RAF SANZIO NEL MDXX (English: Raf(faello) Sanzio owned (this house) in 1520).[21]

25 Casa di Raffaello

25 Casa di Raffaello

26 Quarter of the Florentines

In 1448 Florentine merchants who resided in Rome (many of them settled in the Tiber bend, today's Ponte Rione), founded the Compagnia della Pietà, akin to the Florentine "Misericordia".[91] Both Popes from the Medici family, Leo X and Clement VII (r. 1523-1534), promoted the influx of Florentines. Since 1515 the Commune of Florence had its own consulate in a palace on Via del Consolato that was erected in 1541 and demolished in 1888 to open the Corso Vittorio Emanuele avenue.[92] It had its own laws, its own court, and its own prison. Some of the buildings erected towards the end of the 15th century that once belonged to Florentines (Fig.) are still preserved across from the church of San Giovanni dei Fiorentini:[93]

.jpg) Quarter of the Florentines

Quarter of the Florentines.jpg) Quarter of the Florentines

Quarter of the Florentines.jpg) Quarter of the Florentines

Quarter of the Florentines

27 San Giovanni dei Fiorentini

In 1519 the "nation" of the Florentines received the privilege to build a parish church in honour of John the Baptist from Leo X .[27] The church stands at the northern end of Via Giulia in the Florentine quarter. [27] The church reflects the grandeur and the political self-image of the Medici family, who owned a palazzo right next to the church. It is the largest church on Via Giulia and its construction, started at the beginning of the 16th century, lasted more than 200 years. [27] It combined the efforts of three of Rome's master builders: Giacomo della Porta, Carlo Maderno, and Francesco Borromini. [27] The last two artists were interred in the same tomb at the church.[94] The altarpiece, started by Pietro da Cortona, was continued by Borromini and finished by Ciro Ferri.[94]

.jpg) San Giovanni dei Fiorentini

San Giovanni dei Fiorentini

References

Footnotes

- Today's Via dei Banchi Nuovi - via del Governo Vecchio - piazza di Pasquino - piazza di S.Pantaleo - piazza d'Aracoeli - Campidoglio - Stradone di S.Giovanni

- Today's Via dei Banchi Vecchi - Via del Pellegrino - via dei Giubbonari

- Today's via dei Coronari

- Dante Aligheri: Inferno, canto XVIII, vv. 28–33

- Inscription at the entrance to the Via del Pellegrino: ALEX VI PONT MAX POST INSTAURATAM ADRIANI MOLEM ANGUSTAS VRBIS VIAS AMMPLIARI IVSSIT MCCCCLXXXXVII (Alexander VI. Pont. Max. ordered to widen the narrow streets of the town after the restoration of the Castel Sant'Angelo)

- IVLIO.II.PONT:OPT:MAX:QVOD FINIB:DITIONIS.S.R.E.PROLATIS ITALIAQ:LIBERATA VRBEM ROMAM OCCVPATE SIMILIOREM QVAM DIVISE PATEFACTIS DIMENSIS Q: VIIS PRO MAIESTATE IMPERII ORNAVIT (Julius II p.o.m. who extended the power of the Holy Roman Church and freed Italy. The city of Rome, which resembled a conquered rather than a properly planned one, he embellished for the glory of the Empire)

- Inscription above the portal: IUSTITIAE ET CLEMENTIAE SECURIORI AC MITlORI REORUM CUSTODIAE NOVUM CARCEREM INNOCENTIUS X PONT. MAX. POSUIT ANNO DOMINI MDCLV (Innocent X. P.M. built the new prison in the year of the Lord 1655, for justice, leniency for the safe and humane custody of convicts)

- Inscription (Fig.) on the façade: DOMVS/ANTONII/SANGALLI/ARCHITECTI/MDLIII (house of the architect Antonio Sangallo 1553)

Citation Notes

- Delli 1988, p. 472.

- Bruschi 1971.

- Delli 1988, p. 473.

- Temple 2011, p. 57.

- Gigli 1990, p. 38.

- Gigli 1990, p. 40.

- Pietrangeli 1979, p. 82.

- Infessura 1890, p. 79 f.: February 1475.

- Castagnoli 1958, p. 378.

- Pietrangeli 1979, p. 8.

- Castagnoli 1958, p. 380-381.

- Portoghesi 1970, p. 19.

- Castagnoli 1958, p. 380.

- Temple 2011, p. 124.

- Temple 2011, p. 67-68.

- Dante 1980.

- Giorgio Vasari: Vita di Donato Bramante – 1568

- Pietrangeli 1981, p. 52.

- Castagnoli 1958, p. 382.

- Pietrangeli 1981, p. 40.

- Pietrangeli 1981, p. 36.

- Delli 1988, p. 504.

- Armellini 1891, p. 424.

- Pietrangeli 1979, p. 76.

- Castagnoli 1988, p. 415.

- Castagnoli 1958, p. 392.

- Pietrangeli 1981, p. 16.

- Pietrangeli 1979, p. 78.

- Pietrangeli 1979, p. 9.

- Pietrangeli 1979, p. 10.

- J. A. F. Orbaan, ed. (1920). Documenti del Barocco Romano (in Italian). Roma: Miscellanea della R. Società Romana di Storia Patria. p. 58 [c440] (1). Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- Gigli 1958, p. 118.

- Ceccarelli 1940, p. 25-26.

- Pietrangeli 1979, p. 13.

- Pietrangeli 1979, p. 44.

- Pietrangeli 1981, p. 56.

- Pietrangeli 1979, p. 80.

- Delli 1988, p. 474.

- Bertarelli 1925, p. 332.

- Pietrangeli 1981, p. 10.

- Pietrangeli 1979, p. 18-22.

- Elisabeth Rosenthal (29 June 2008). "A Stroll in Rome With a Papal Pedigree-Via Giulia celebrates its 500th birthday this year". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- Pietrangeli 1979, p. 62.

- Pietrangeli 1979, p. 56.

- Pietrangeli 1979, p. 58.

- "Wilhelm Waiblinger" (in Italian). 13 April 2020. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- Callari 1932, p. 213.

- "Palazzo Farnese" (in Italian). Ministère de l’Europe et des Affaires étrangères. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- Pietrangeli 1979, p. 54.

- Pietrangeli 1979, p. 48.

- Pietrangeli 1979, p. 50.

- Rendina, Claudio (11 September 2011). "Il genio di Borromini nei saloni delle feste di casa Falconieri". www.roma.balassiintezet.hu (in Italian). Istituto Balassi. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- Pietrangeli 1979, p. 46.

- "Pontificio Istituto Ecclesiastico Ungherese" (in Italian). Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- Pietrangeli 1979, p. 40.

- Brentano, Carrol (1989). "DELLA PORTA, Guglielmo". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (in Italian). 37. Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana.

- "Fondazione Ducci - Locations - Il Palazzo Cisterna". www.fondazioneducci.org. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- Pietrangeli 1979, p. 36.

- Pietrangeli 1979, p. 38.

- "L'Oratorio di Santa Caterina da Siena in Via Giulia" (in Italian). Arciconfraternita Santa Caterina da Siena. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- Pietrangeli 1979, p. 34.

- Pietrangeli 1979, p. 30.

- Pietrangeli 1979, p. 32.

- Pina Baglioni. "Gli Storici di Via Giulia" (in Italian). Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- Pietrangeli 1979, p. 22.

- "La Storia" (in Italian). Liceo Ginnasio Statale "Virgilio". Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Pietrangeli 1979, p. 28.

- Armellini 1891, p. 423.

- Pietrangeli 1979, p. 24.

- Pietrangeli 1979, p. 26.

- Delli 1988, p. 475.

- Pietrangeli 1979, p. 16.

- Pietrangeli 1979, p. 18.

- Armellini 1891, p. 422.

- Alvaro de Alvariis. "S. Filippo Neri". flickr.com (in Italian). Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- Pietrangeli 1979, p. 14.

- "Direzione Nazionale Antimafia". indicepa.gov.it (in Italian). Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- Pietrangeli 1981, p. 64.

- Pietrangeli 1981, p. 66.

- Pietrangeli 1981, p. 58.

- Pietrangeli 1981, p. 50.

- Pietrangeli 1981, p. 54.

- Armellini 1891, p. 356.

- Pietrangeli 1981, p. 48.

- Pietrangeli 1981, p. 46.

- Pietrangeli 1981, p. 42.

- Pietrangeli 1981, p. 44.

- Hans Höller. Ingeborg Bachmann (in German). Rowohlt Verlag GmbH. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- Pietrangeli 1981, p. 34.

- Alessandro Venditti. "Palazzo Medici Clarelli" (in Italian). Specchio Romano. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- Pietrangeli 1981, p. 14.

- Pietrangeli 1981, p. 26.

- Pietrangeli 1981, p. 24.

- Pietrangeli 1981, p. 20.

Sources

- Vasari, Giorgio (1568). Le vite de’ più eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori italiani, da Cimabue insino a' tempi nostri (in Italian). Firenze: Giunti.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gigli, Giacinto (1958) [1670]. Diario romano, 1608-1670 (in Italian). Roma: Staderini.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Infessura, Stefano (1890) [1494]. Oreste Tommasini (ed.). Diario della città di Roma (in Italian). Roma: Forzani e C.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Armellini, Mariano (1891). Le chiese di Roma dal secolo IV al XIX (in Italian).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bertarelli, Luigi Vittorio (1925). Roma e dintorni (in Italian). Milano: Touring Club Italiano.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Callari, Luigi (1932). I Palazzi di Roma (in Italian). Roma: Ugo Sofia-Moretti.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ceccarelli, Giuseppe ("Ceccarius") (1940). Strada Giulia (in Italian). Roma: Danesi.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Castagnoli, Ferdinando; Cecchelli, Carlo; Giovannoni, Gustavo; Zocca, Mario (1958). Topografia e urbanistica di Roma (in Italian). Bologna: Cappelli.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Portoghesi, Paolo (1970). Roma del Rinascimento (in Italian). Milano: Electa.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bruschi, Arnaldo (1971). "Donato Bramante". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (in Italian). 13. Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pietrangeli, Carlo (1979). Guide rionali di Roma (in Italian). Regola (III) (2 ed.). Roma: Fratelli Palombi Editori.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dante, Francesco (1980). "Agostino Chigi". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (in Italian). 24. Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pietrangeli, Carlo (1981). Guide rionali di Roma (in Italian). Ponte (IV) (3 ed.). Roma: Fratelli Palombi Editori.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Delli, Sergio (1988). Le strade di Roma (in Italian). Roma: Newton & Compton.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gigli, Laura (1990). Guide rionali di Roma (in Italian). Borgo (I). Roma: Fratelli Palombi Editori.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Temple, Nicholas (2011). Renovatio Urbis; Architecture, urbanism and ceremony in the Rome of Julius II. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-81848-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Luigi Salerno; Luigi Spezzaferro; Manfredo Tafuri (1973). Via Giulia: una utopia urbanistica del 500. Rome: Staderini.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Via Giulia. |