Rail transport in Sudan

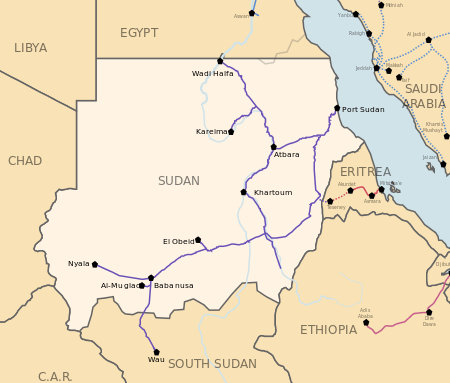

Sudan has 4,725 kilometers of narrow-gauge, single-track railways that serve the northern and central portions of the country. The main line runs from Wadi Halfa on the Egyptian border to Khartoum and southwest to El-Obeid via Sannar and Kosti, Sudan, with extensions to Nyala in Southern Darfur and Wau in Western Bahr al Ghazal, South Sudan. Other lines connect Atbarah and Sannar with Port Sudan, and Sannar with Ad Damazin. A 1,400-kilometer line serves the al Gezira cotton-growing region. A modest effort to upgrade rail transport is currently underway to reverse decades of neglect and declining efficiency. Service on some lines may be interrupted during the rainy season.

Statistics

total: 5,063 km

3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) gauge: 4,347 km

610 mm (2 ft) gauge plantation lines: 716 km

note:

the main line linking Khartoum to Port Sudan carries over two-thirds of Sudan's rail traffic

Sudan Railways

The main system, Sudan Railways, which was operated by the government-owned Sudan Railways Corporation (SRC), provided services to most of the country's production and consumption centers. The other line, the Gezira Light Railway, was owned by the Sudan Gezira Board and served the Gezira Scheme and its Manaqil Extension. Rail dominated commercial transport in the early years but competition from the highways increased rapidly and by 2013, 90% of inland transport in Sudan was by road.[1] The main rail system was reorganised into two companies - the SRC which owned the physical assets of the Sudan Railways and another company which organised the operations with participation of private companies (10 private companies were reported to be running operations in different lines in 2013).[1][2]

History

The pre-eminence of the rail system is based on historical developments that led to its construction as an adjunct to military operations, although the first line, started by the Khedive Isma'il Pasha in 1874 from Wadi Halfa to Sarras about 54 km upstream on the East bank of the Nile River, originally a commercial undertaking.[3] This line, which was stopped by the Governor-General Gordon in 1878 to reduce expenditure, had not proved viable commercially. It was extended by the Nile Expedition in 1884 to Akasha on the Nile but was destroyed by Dervishes when the Anglo-Egyptian troops withdrew to Wadi Halfa. A 20-mile railway line was built by John Aird & Co. from Suakin on the Red Sea inland to Otau in 1884 during the Red Sea Expedition but was abandoned in 1885.[4] The Wadi Halfa - Saras line was extended again to Kerma, above the third cataract in May 1887 to support the Anglo-Egyptian Dongola Expedition against the Mahdiyah.[5] This line was poorly constructed and of little other use, was abandoned in 1905.[4][6][3]

The first segment of the present-day Sudan Railways, from Wadi Halfa to Abu Hamad on the Nile, was also a military undertaking. It was built by the British for use in General Herbert Kitchener's drive against to the Mahdiyah in the late 1890s. The line was pushed to Atbarah on the Nile in 1897 during the campaign and after the defeat of the Mahdiyah in 1898 was continued to Khartoum, which it reached on the last day of 1899.[4] The line was built to 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in) gauge track specifications, the result apparently of Kitchener's pragmatic use of the rolling stock and rails of that gauge from the old line. This gauge was used in all later Sudanese mainline construction.[3]

The line opened a trade route from central Sudan through Egypt to the Mediterranean and beyond. It became uneconomic because of the distance and the need for trans-shipment via the Nile, and in 1904 construction of a new line from Atbarah to the Red Sea was undertaken with the line complete in October 1905.[4] In 1906 the new line reached recently built Port Sudan to provide a direct connection between Khartoum and ocean-going transport.[3]

During the same decade, a line was also built from Khartoum southward to Sannar, the heart of the cotton-growing region of Al Jazirah. A westward continuation reached El-Obeid, then the country's second largest city and center of gum arabic production, completed in February 1912.[4] In the north, a branch line was built from near Abu Hamad to Kuraymah that tied the navigable stretch of the Nile between the fourth and third cataracts into the transport system. Traffic in this case, however, was largely inbound to towns along the river, a situation that still prevailed in 1990.[3]

In the 1920s, a spur of the railway was built from Hayya, a point on the main line 200 km southwest of Port Sudan, south to the cotton-producing area near Kassala, then on to the grain region of Al Qadarif, and finally to a junction with the main line at Sennar. Much of the area's traffic, which formerly had passed through Khartoum, has since moved over this line directly to Port Sudan.[3]

The final spur of railway construction began in the 1950s.[7] It included extension of the western line to Nyala (1959) in Darfur Province and of a southwesterly branch to Wau (1961), southern Sudan's second largest city, located in the province of Bahr el Ghazal. This essentially completed the Sudan Railways network, which in 1990 totalled about 4800 route km[3] [there were small later extensions from Abu Gabra to El Muglad (52 km in 1995), El Obeid to the El Obeid refinery (10 km) and El Ban to the Merowe Dam (10 km)[8]].

| Route | Years | Length |

|---|---|---|

| Wadi Halfa- Abu Hamad | 1897–1898 | 350 km |

| Abu Hamad – Atbara | 1898 | 244 km |

| Atbara – Khartoum | 1898–1900 | 313 km |

| Atbara - Port Sudan | 1904–1906 | 474 km |

| Station No. 10 – Karima | 1905 | 222 km |

| Khartoum -Kosti – El Obeid | 1909–1911 | 689 km |

| Hayya - Kassala | 1923–1924 | 347 km |

| Kassala - Gedarif | 1924–1928 | 218 km |

| Gedarif – Sennar | 1928–1929 | 237 km |

| Sennar- Damazin | 1953–1954 | 227 km |

| Aradeiba Junction – Babanusa | 1956–1957 | 354 km |

| Babanusa – Nyala | 1957–1959 | 335 km |

| Babanusa – Wau | 1959–1962 | 444 km |

| Girba - Digiam | 1962 | 70 km |

| Muglad - Abu Gabra | 1995 | 52 km |

Source:[9]

Diesel traction

Conversion of Sudan Railways to diesel traction started in the late 1950s, but a few mainline steam locomotives continued in use in 1990, serving lines having lighter weight rails.[3] Through the 1960s, rail essentially had a monopoly on transportation of export and import trade, and operations were profitable. In the early 1970s, losses were experienced, and, although the addition of new diesel equipment in 1976 was followed by a return to profitability, another downturn had occurred by the end of the decade. The losses were attributed in part to inflationary factors, the lack of spare parts, and the continuation of certain lines characterized by only light traffic, but retained for economic development needs and for social reasons.[3] A number of South African diesel locomotives are in use in Sudan.

Downturn

The chief cause of the downturn appeared to have been loss of operational efficiency. Worker productivity had declined. For example, repair of locomotives was so slow that only about half of the total number were usually operational. Freight car turnaround time had lengthened considerably, and the reported slowness of management to meet growing competition from road transport was also a major factor. A former official in the Sudan train union blamed Gaafar Nimeiry's attempts to crush the unions (who had organised numerous strikes on the railway) by firing 20,000 well qualified employees from 1975-1991.[10] The road system, although generally more expensive, was used increasingly for low-volume, high-value goods because it could deliver more rapidly—2 or 3 days from Port Sudan to Khartoum, compared with 7 or 8 days for express rail freight and up to two weeks for ordinary freight. In 1982, only one to two percent of freight (and passenger) trains arrived on time.[11] The gradual erosion of freight traffic was evident in the drop from more than 3 million tons carried annually at the beginning of the 1970s to about 2 million tons at the end of the decade. The 1980s also saw a steady erosion of tonnage as a result of a combination of inefficient management, union intransigence, the failure of agricultural projects to meet production goals, the dearth of spare parts, and the continuing civil war. The bridge at Aweil was destroyed in the 1980s[3] and Wau was without rail access for over 20 years. The line to Wau was reopened in 2010 but Wau became part of South Sudan when it declared independence in 2011.[12] During the civil war in the south (1983–2005) military trains went as far as Aweil accompanied by large numbers of troops and militia, causing great disruption to civilians and humanitarian aid organisations along the railway line.[3]

Modernisation

Despite the rapidly growing use of roads, rail has remained of paramount importance because of its ability to move at lower cost the large volume of agricultural exports and to transport inland the increasing imports of heavy capital equipment and construction materials for development, such as requirements for oil exploration and drilling operations. Efforts to improve the rail system reported in the late 1970s and the 1980s included laying heavier rails, repairing locomotives, purchasing new locomotives, modernizing signaling equipment, expanding training facilities, and improving locomotive and rolling-stock repair facilities. One project would double-track the line from Port Sudan to the junction of the branch route to Sannar, thus in effect doubling the Port Sudan-Khartoum rail line. Substantial assistance was furnished for these and other stock and track improvement projects by foreign governments and organizations, including the European Development Fund, the AFESD, the International Development Association, Britain, France, China and Japan. Implementation of much of this work was hampered by political instability in the 1980s, debt, the dearth of hard currency, the shortage of spare parts, and import controls. A former rail union official also blamed the Sudanese president Omer Hassan al-Bashir who took office in 1989 and continued the previous regime's policy of mass firing, forcing into early retirement or transferring to out of the way locations of qualified railroad employees and replacing them with incompetent political appointees.[10] Rail was estimated in mid-1989 to be operating at less than 20% of capacity. In 2015 the railways were said to have 60 trains available but the maximum speed they could travel was 40 km/h due to poor railway tracks.[13][14]

In 2015 the Sudanese president Omer Hassan al-Bashir promised to modernise and upgrade the Sudanese railways with Chinese funds and technical assistance[15] after years of maladministration and neglect.[13] However a 2016 article noted that many Chinese firms had given up dealing with Sudan because of sanctions and pressure from the USA.[10]

Gezira Light Railway

.jpg)

The Gezira Light Railway, one of the largest light railways in Africa, evolved from tracks laid in the 1920s' construction of the canals for the Gezira Scheme. At the time, rail had about 135 route km of 2 ft (610 mm) narrow gauge track. As the size of the project area increased, the railway was extended and by the mid-1960s consisted of a complex system totaling 716 route km. Its primary purpose has been to serve the farm area by carrying cotton to ginneries and fertilizers, fuel, food, and other supplies to the villages in the area.[8] Operations usually have been suspended during the rainy season.

Tokar - Trinkitat Light Railway

The Tokar - Trinkitat Light Railway was built in 1921/1922 at 600 mm (1 ft 11 5⁄8 in) narrow gauge and was 29 km long,[16] primarily used for the export of the cotton crop from Tokar. It used ex-War Department Light Railways rolling stock and Simplex locomotives. It was absorbed by Sudan Railways in 1933 and closed in 1952.[17]

Proposed Nyala - Chad extension

In 2011 funds were reportedly obtained to construct an extension from Nyala to Chad[18] - the financing was to be obtained from China.[19] In 2012 a contract to build a rail line from the Sudan-Chad border to the capital of Chad, N'Djamena was also reported to be signed.[20] But in 2014 it was reported that although Sudan and Chad had agreed to stop supporting rebels in each other's countries, the US$2 billion project had still not been signed nor started.[21]

South Sudan independence

After the Declaration of Independence of South Sudan in 2011, 248 km of the Babanousa-Wau line was no longer within (north) Sudanese territory.

Specifications

Links to neighboring countries

References

- Sudan: Interim Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (Issues 13-318 of IMF Staff Country Reports). International Monetary Fund. Middle East and Central Asia Dept. 2013. pp. Section 210. ISBN 9781475598049.

- "Sudan's transport system a key cog in economic development". Leading Edge Guides. 2016-09-27. Retrieved 2017-07-15.

- "Sudan Railways Corporation (SRC)". Institute of Developing Economies Japan External Trade Organization. 2007. Retrieved 2010-07-14.

- "Sudan's rail and river transport". The Gunboat, Incorporating Melik Bulletin. London, UK: Melik Society: 33–38. January 2011. - extracts from Pinkney, Frederick George Augustus (1926). Sudan Government Railways and Steamers. Institution of Civil Engineers. Selected Engineering Papers. 35. UK: Institution of Civil Engineers. pp. 1–19. ASIN B0017DEERE.

- Derek A. Welsby (January 2011). "The Wadi Halfa to Kerma railway". The Gunboat, Incorporating Melik Bulletin. London, UK: Melik Society: 31–32.

- Gleichen, Edward, ed. (1905). The Anglo-Egyptian Sudan: A Compendium Prepared by Officers of the Sudan Government. 1. London, UK: His Majesty's Stationery Office. pp. 213–215. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- For an overview of the railway in 1952, see "Sudan Railways," in Railroad Magazine October 1952, at pp. 36-47. The article is illustrated with black and white photos of what was then a flourishing railroad.

- Ali, Hamid Eltgani (2014). Darfur's Political Economy: A Quest for Development (Europa Country Perspectives). Routledge. p. 257. ISBN 9781317964643.

- "Sudan Railways Facts and Figures 2007" (PDF). Sudan Railways Corporation. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-08-20. Retrieved 2017-07-15.

- Foltyn, Simona (2016-11-14). "Riding the Nile train: could lifting US sanctions get Sudan's railway on track?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2017-07-15.

- Due, John F. (February 1983). "Trends in Rail Transport in Four African Countries Zimbabwe, Zambia, Tanzania, Sudan (BEBR Faculty working paper No. 937)". College of Commerce and Business Administration, Bureau of Business and Economic Research. University of Illinois, USA: 39–56. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Kone, Solomane, ed. (2013). "South Sudan: An Infrastructure Action Plan; Chapter 7.4.1 Current Status of the railways network" (PDF). African Development Bank Group. p. 192.

- "Bashir vows to restore Sudan's railway network". The Sudan Tribune. Sudan. 5 April 2015. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- Mohamed Nureldin Abdallah (20 August 2013). "Getting Sudan;s railways on track". Reuters. Sudan. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- "All aboard! Sudan's sleek new Nile Train a rarity". Yahoo! Finance. 20 April 2014. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- Bisheshwar, Prasad (1963). "East African Campaign, 1940-41 (Chapter 2) ; Official History of the Indian Armed Forces In the Second World War". Ibiblio. Retrieved 2017-07-15.

- Gunston, Henry (2001). Narrow Gauge by the Sudanese Red Sea Coast; the Tokar - Trinkitat Light Railway and other small railways. Norfolk, UK: Plateway Press. ISBN 9781871980462.

- "Prefeasibility Study for the Construction of a new Railway Line Nyala - Elgeneina – Adri (Chad border)". Sudan Railways Corporation. Archived from the original on 2015-09-06. Retrieved 2017-07-15.

- Toby Collins (31 July 2011), "Sudan-Chad railway funds secured", www.sudantribune.com, Sudan Tribune

- "Work to begin on Chad rail network", www.railwaygazette.com, Railway Gazette International, 13 January 2012

- Otieno, Patrick (2014-07-22). "Sudan, Chad to build a railway at US$2b". Construction Review Online. Retrieved 2017-07-15.

- "DLW locomotives for export to Sudan". Hindustan Times. 2005-07-11. Archived from the original on 2012-10-25.

- "Rs. 80-crore target for railway spares export". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 2004-11-11.

- Singh, Animesh (2005-07-13). "Second batch of Indian locomotives for Sudan soon". Sudan Tribune. Retrieved 2017-07-15.

- "Cape gauge locos despatched to Sudan". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 2005-10-20.

- "EGYPT-SUDAN RAIL LINK". Railways Africa. 31 May 2008. Archived from the original on 11 December 2008.

- Johnston, Cynthia (2009-07-08). "Egypt studies building $500 million rail link to Sudan". Reuters UK. Retrieved 2017-07-15.

- Standard Gauge link

Further reading

- Gunston, Harry (2001). Narrow gauge by the Sudanese Red Sea Coast. East Harling: Plateway Press. ISBN 1871980461.

- Robinson, Neil (2009). World Rail Atlas and Historical Summary. Volume 7: North, East and Central Africa. Barnsley, UK: World Rail Atlas Ltd. ISBN 978-954-92184-3-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rail transport in Sudan. |

- UN Map

- UNHCR Atlas Map

- Interactive map of Sudan and South Sudan railways

- Sudan Railways Corporation

- Winchester, Clarence, ed. (1936), "Through desert and jungle", Railway Wonders of the World, pp. 193–199 illustrated description of the Sudan railways