Sargon II

Sargon II (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: ![]()

| Sargon II | |

|---|---|

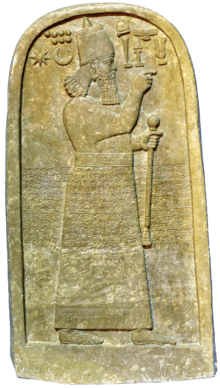

| |

Alabaster bas-relief from the royal palace of Sargon II at Dur-Sharrukin, depicting the king. Exhibited at the Iraq Museum. | |

| King of the Neo-Assyrian Empire | |

| Reign | 722–705 BC |

| Predecessor | Shalmaneser V |

| Successor | Sennacherib |

| Born | c. 762 BC[1] |

| Died | 705 BC (aged c. 57) Tabal |

| Spouse | Ra'īmâ Atalia |

| Issue | Sennacherib At least 4 other sons Ahat-abisha |

| Akkadian | Šarru-kīn Šarru-ukīn |

| Dynasty | Sargonid dynasty |

| Father | Tiglath-Pileser III (?) |

| Mother | Iabâ (?) |

| Religion | Ancient Mesopotamian religion |

The king probably took the name Sargon from the legendary ruler Sargon of Akkad, who had founded the Akkadian Empire and ruled most of Mesopotamia almost two thousand years prior. Through his military campaigns aimed at world conquest, Sargon II aspired to follow in the footsteps of his ancient namesake. Sargon sought to project an image of piety, justice, energy, intelligence and strength and remains recognized as a great conqueror and tactician due to his many military accomplishments.

His greatest campaigns were his 714 BC war against Urartu, Assyria's northern neighbor, and his 710–709 BC reconquest of Babylon, which had successfully re-established itself as an independent kingdom upon Shalmaneser V's death. In the war against Urartu, Sargon circumvented the series of Urartian fortifications alongside the border of the two kingdoms by marching around them along a longer route and he successfully seized and plundered Urartu's holiest city, Musasir. In the Babylonian campaign, Sargon also attacked from an unexpected front, first marching alongside the Tigris river and then attacking the kingdom from the southeast rather than the north.

From 713 BC to the end of his reign, Sargon oversaw the construction of a new city which he intended to serve as the capital of the Assyrian Empire, Dur-Sharrukin (meaning "Sargon's fortress"). After the Babylonian conquest he resided at Babylon for three years, with his crown prince and heir Sennacherib serving as regent in Assyria, but he moved to Dur-Sharrukin upon its near completion in 706 BC. Sargon's death on campaign in Tabal in 705 BC and the loss of his body to the enemy was seen by the Assyrians as an ill omen and Sennacherib immediately abandoned Dur-Sharrukin upon becoming king, instead moving the capital to the city Nineveh.

Background

Political situation in Assyria

Sargon's reign was immediately preceded by the reigns of the two kings Tiglath-Pileser III (r. 745–727 BC) and Shalmaneser V (r. 727–722 BC). Before Tiglath-Pileser came to the throne in 745 BC, Assyria had been continually ruled by the Adaside dynasty since the 18th century BC, a timespan of roughly a thousand years. Though Tiglath-Pileser claimed to be a son of the king Adad-nirari III (r. 811–783 BC) and thus a member of the Adaside bloodline, the accuracy of this claim is doubtful; Tiglath-Pileser seized the Assyrian throne in the midst of a civil war and slaughtered the entire then incumbent royal family (including the incumbent king, his supposed nephew, Ashur-nirari V).[5] Tiglath-Pileser's claim to relation with the preceding dynasty appears only in king lists, in his own personal inscriptions there is a noticeable lack of familial references (otherwise common in inscriptions by Assyrian kings) and these instead stress that he had been called upon and personally appointed by Assur, the god of Assyria.[6]

Though it was chiefly during the time of Sargon and his successors that Assyria was transformed from a kingdom primarily based in the Mesopotamian heartland to a truly multinational and multi-ethnic empire, the foundations which allowed this development were laid during Tiglath-Pileser's reign through extensive civil and military reforms. Furthermore, Tiglath-Pileser began a successful series of conquests, subjugating the kingdoms of Babylon and Urartu and conquering the Mediterranean coastline. His successful military innovations, including replacing conscription with levies being supplied from each province, made the Assyrian army one of the most effective armies assembled up until that point.[7]

After a reign of only five years, Tiglath-Pileser's son Shalmaneser V was replaced as king by Sargon, supposedly another of Tiglath-Pileser's sons. Nothing is known of Sargon before he became king.[8] Probably born c. 762 BC, Sargon would have grown up during a period of civil unrest in Assyria. Outbreaks of rebellion and plague marked the ill-fated reigns of kings Ashur-dan III (r. 773–755 BC) and Ashur-nirari V (r. 755–745 BC). During their reigns, the prestige and power of Assyria had dramatically declined, a trend which was reversed only during the tenure of Tiglath-Pileser.[1] The exact events surrounding the death of Sargon's predecessor Shalmaneser V and Sargon's rise to the throne are not entirely clear.[8] It is most often assumed that Sargon deposed and assassinated Shalmaneser in a palace coup.[7]

Usurpation

Whether Sargon usurped the Assyrian throne or not is disputed. That he would have been a usurper is mainly based on one of several possible interpretations of the meaning behind his name (that it would mean "the legitimate king") and on that his numerous inscriptions rarely discuss his origin. This absence of explanation as how the king fit into the established genealogy of the Assyrian kings is not only a feature of Sargon's inscriptions but also a feature of the inscriptions of both his supposed father, Tiglath-Pileser, and of his son and successor, Sennacherib. Though Tiglath-Pileser is known to have been a usurper, Sennacherib was the legitimate son and heir of Sargon.[9] Several explanations have been offered for Sennacherib's silence on his father, the most accepted being that Sennacherib was superstitious and fearful of the terrible fate that befell his father.[10] Alternatively, Sennacherib might have wished to inaugurate a new period of Assyrian history,[9] or might have felt resentment against his father.[11]

Sargon did sometimes reference Tiglath-Pileser. He explicitly identified himself as Tiglath-Pileser's son in only two of his many inscriptions and referred to his "royal fathers" in one of his stelae.[9] If Sargon was the son of Tiglath-Pileser, he would probably have held some important administrative or military position during the reigns of his father and brother, but this can not be verified since the name used by Sargon before he became king is unknown. It is possible that he had some form of priestly role since he showed repeated affection for religious institutions throughout his reign and he might have been the important sukkallu ("vizier") of the city Harran. Whether he was the son of Tiglath-Pileser or not, Sargon wished to stand apart from his predecessors and is today seen as the founder of Assyria's final ruling dynasty, the Sargonid dynasty.[12] There are references as late as the 670s, during the reign of Sargon's grandson Esarhaddon, to the possibility that "descendants of former royalty" might try to seize the throne. This suggests that the Sargonid dynasty was not necessarily well connected to previous Assyrian monarchs.[13]

Regardless of his parentage, the succession from Shalmaneser V to Sargon is likely to have been awkward.[14] Shalmaneser is only mentioned in one of Sargon's inscriptions:

Shalmaneser, who did not fear the king of the world, whose hands have brought sacrilege in this city [Assur], put on his people, he imposed the compulsory work and a heavy corvée, paid them like a working class. The Illil of the gods, in the wrath of his heart, overthrew his rule and appointed me, Sargon, as king of Assyria. He raised my head; let me take hold of the scepter, the throne and the tiara.[14]

This inscription serves more to explain Sargon's rise to the throne than to explain Shalmaneser's downfall. As attested in other inscriptions, Sargon did not see the injustices described as actually having been imposed by Shalmaneser V. Other inscriptions by Sargon state that the tax exemptions of important cities like Assur and Harran had been revoked "in ancient times" and the compulsory work described would have been conducted in the reign of Tiglath-Pileser, not Shalmaneser.[14]

Name

.jpg)

Two previous ancient Mesopotamian kings had used the name Sargon; Sargon I, a minor Assyrian king of the 19th century BC, and the far more famous Sargon of Akkad, who had ruled most of Mesopotamia as the first king of the Akkadian Empire in the 24th to 23rd centuries BC.[15] Sargon II sharing the name of one of Mesopotamia's greatest ancient conquerors was not coincidental; names in ancient Mesopotamia were important and deliberate. Sargon himself appears to have mainly connected his name to justice.[16] This is illustrated in several inscriptions, such as the following, which relates to Sargon paying those who had owned the land he chose to construct his capital Dur-Sharrukin on:

In accordance with the name which the great gods have given me – to maintain justice and right, to give guidance to those who are not strong, not to injure the weak – the price of the fields of that town [Khorsabad] I paid back to their owners ...[16]

The name was most commonly written Šarru-kīn (or Šarru-kēn), with another version, Šarru-ukīn, only being attested in less important royal inscriptions and letters. The direct meaning of the name, based on Sargon's self-perception, is commonly interpreted as "the faithful king" in the sense of righteousness and justice. Another alternative is that Šarru-kīn is a phonetic reproduction of the contracted pronunciation of Šarru-ukīn to Šarrukīn, which means that it should be interpreted as "the king has obtained/established order", possibly referencing disorder either during the reign of his predecessor or disorder created by Sargon's usurpation. The modern conventional rendering of the name, "Sargon", probably derives from the spelling of his name in the Bible, srgwn.[3]

Sargon's name was probably not a birth name, but rather a throne name he adopted upon his rise to the throne. It is far more likely that he chose the name based on its use by the famous Akkadian king rather than its use by his predecessor in Assyria. In late Assyrian texts, the name of both Sargon II and Sargon of Akkad are written with the same spellings and Sargon II is sometimes explicitly called the "second Sargon" (Šarru-kīn arkû). Sargon as such likely sought to emulate aspects of the ancient Akkadian king.[4] Though the exact extent of the ancient Sargon's conquests had been forgotten by the time of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, the legendary ruler was still remembered as a "conqueror of the world" and would have been an enticing model to follow.[17]

Another possible interpretation is that the name means "the legitimate king" and thus might have been a name chosen to enforce the king's legitimacy after his usurpation of the throne.[7] Sargon of Akkad had also risen to the throne through usurpation, beginning his reign by seizing power from the ruler of the city Kish, Ur-Zababa.[4]

Reign

Early reign and rebellions

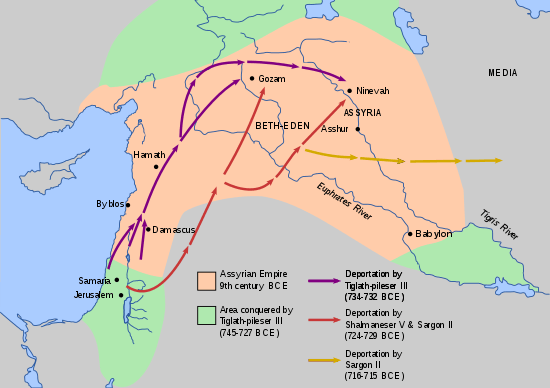

Sargon was already middle-aged when he became king, probably in his forties,[18] and resided in the palace of King Ashurnasirpal II (r. 883–859 BC) at Kalhu.[19] Sargon's predecessor, Shalmaneser V, had tried to continue the expansionism of his father but his military efforts had been both slower and less efficient than those of Tiglath-Pileser III. Notably, his prolonged siege of Samaria, which had lasted three years, was still ongoing by the time of his death. After Sargon ascended to the throne, he quickly abolished the tax and labor policies that were in place (and which he criticized in his later inscriptions) and then proceeded to quickly resolve Shalmaneser's campaigns. Samaria was swiftly conquered and through its conquest, the Kingdom of Israel fell. According to Sargon's own inscriptions, 27,290 Jews were deported from Israel and resettled across the Assyrian Empire, following the standard Assyrian way of dealing with defeated enemy peoples through resettlement. This specific resettlement resulted in the famous loss of the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel.[11]

Initially, Sargon's rule was met with opposition in the Assyrian heartland and in regions on the empire's periphery,[20] possibly on account of him being a usurper.[7] Among the most prolific early rebels against Sargon were several of the previously independent kingdoms in the Levant, such as Damascus, Hamath and Arpad. Hamath, led by a man called Yau-bi'di, became the leading power of this Levantine revolt, but was successfully crushed in 720 BC.[20] After Hamath had been destroyed, Sargon continued by defeating Damascus and Arpad in battle at Qarqar in the same year. With order restored, Sargon returned to Kalhu and forced 6,000–6,300 "guilty Assyrians" or "ungrateful citizens", people who had either rebelled in the heartland of the empire or had failed to support Sargon's rise to the throne, to move to Syria and rebuild Hamath and the other cities destroyed or damaged in the conflict.[11][20]

The political uncertainty in Assyria also led to a rebellion in Babylonia, the once independent kingdom in southern Mesopotamia. Marduk-apla-iddina II, the leader of the Bit-Yakin, a powerful Babylonian tribe, seized control of Babylon and announced an end of Assyrian rule over the region. Sargon's response to this insurrection was to immediately march his army to defeat Marduk-apla-iddina. To counteract Sargon, the new Babylonian king quickly allied with one of Assyria's ancient enemies, Elam, and assembled a massive army. In 720 BC, the Assyrians and Elamites (the Babylonians arriving too late to the battlefield to actually fight) met in battle at the plains outside the city Der, the same battlefield where the Persians two centuries later would defeat the forces of the last Babylonian king, Nabonidus. Sargon's army was defeated and Marduk-apla-iddina secured control of southern Mesopotamia.[20]

Conquest of Carchemish and dealings with Urartu

In 717 BC, Sargon conquered the small, but wealthy, Kingdom of Carchemish. Carchemish was positioned at a crossroads between Assyria, Anatolia and the Mediterranean, controlled an important crossing of the Euphrates and had for centuries profited from international trade. Further increasing the prestige of the small kingdom was its role as the recognized heir of the ancient Hittite Empire of the 2nd millennium BC, holding a semi-hegemonic position among the Anatolian and Syrian kingdoms in former Hittite lands.[20]

To attack Carchemish, previously an Assyrian ally, Sargon violated existing treaties with the kingdom, using the excuse that Pisiri, Carchemish's king, had betrayed him to his enemies. There was little the small kingdom could do to resist Assyria, and so it was conquered by Sargon. This conquest allowed Sargon to secure Pisiri's large treasury, including 330 kilograms of purified gold, large amounts of bronze, tin, ivory and iron and over 60 tonnes of silver.[20] The treasury secured from Carchemish was so rich in silver that the Assyrian economy changed from being primarily bronze-based to being primarily silver-based.[11] This allowed Sargon to compensate the increasing costs of his intense deployments of the Assyrian army.[20]

Sargon's 716 BC campaign saw him attack the Mannaeans in modern Iran, plundering their temples, and in 715 BC, Sargon's armies were in the region called Media, conquering settlements and cities and securing treasure and prisoners to be sent back to Kalhu.[11] During these two northern campaigns, it had become evident that the northern Kingdom of Urartu, a precursor of the later Armenia and a frequent enemy of the Assyrians, presented a persistent problem. Though the kingdom had been suppressed by Tiglath-Pileser III, it had not been completely conquered or defeated and had risen again during Shalmaneser V's time as king and had begun making repeated border incursions into Assyrian territory.[11]

These border incursions continued into Sargon's reign. In 719 BC and 717 BC, the Urartians conducted minor invasions across the northern border, forcing Sargon to send troops to keep them away. A full-scale assault was made in 715 BC, during which the Urartians successfully seized 22 Assyrian border cities. Though the cities were quickly retaken and Sargon retaliated by razing the southern provinces of Urartu, the king knew that the incursions would continue and would consume important time and resources each time. To triumph, Sargon needed to defeat Urartu once and for all, a task which had been impossible for previous Assyrian kings due to the kingdom's strategic location in the foothills of the Taurus Mountains; when the Assyrians invaded, the Urartians usually simply retreated into the mountains to regroup and later return. Though Urartu were Sargon's enemies, his own inscriptions speak of the kingdom with respect, showing admiration for its swift communication system, its horses and its canal systems.[11]

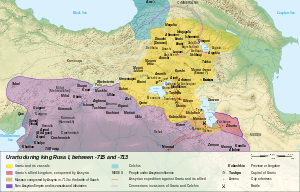

Campaign against Urartu

In 715 BC, Urartu had been severely weakened by a number of its enemies. First, King Rusa I's campaign against the Cimmerians, a nomadic Indo-European people in the central Caucasus, had been a disaster, with the army defeated, the commander in chief Kakkadana captured and the king fleeing the battlefield. Following their victory, the Cimmerians had attacked Urartu, penetrating deep into the kingdom as far as south-west of Lake Urmia. In the same year, the Mannaeans, subjected to Urartu and living around Lake Urmia, rebelled due to the 716 BC Assyrian attack against them and had to be suppressed.[21]

Sargon probably perceived Urartu as a weak target following the news of Rusa I's defeat against the Cimmerians. Rusa was aware that the Assyrians were likely to invade his kingdom and had probably kept most of his remaining army by Lake Urmia following his victory over the Mannaeans as the lake was close to the Assyrian border. Because the kingdom had been threatened by the Assyrians before, the southern border of Urartu was not entirely defenseless.[21] The shortest path from Assyria to Urartu's heartland went through the Kel-i-šin pass in the Taurus Mountains. One of the most important places in all of Urartu, the holy city Musasir, was located just west of this pass and as such it required extensive protection. This protection was to come from a series of fortifications and during his preparations for Sargon's attack, Rusa ordered the construction of a new fortress called the Gerdesorah. Though the Gerdesorah was small, measuring about 95 x 81 metres (311.7 x 265.7 ft), it was strategically positioned on a hill about 55 metres (180.4 ft) higher than the rest of the terrain and had 2.5 (8.2 ft) metre thick walls and defensive towers.[22] One weakness of the Gerdesorah was that it had not yet completely finished construction, only starting to be built c. mid-June of 714 BC.[23]

Sargon left Kalhu to attack Urartu in July 714 BC and would have needed at least ten days to reach the Kel-i-šin pass, 190 kilometres (118 miles) away. Though the pass was the fastest way into Urartu, Sargon chose to not take it. Instead, Sargon marched his army through the rivers Great and Little Zab over the course of three days before halting at the great mountain Mount Kullar (the location of which remains unidentified) and then deciding that he would attack Urartu by a longer route, through the region Kermanshah. The reasoning behind this route was probably not fear of Urartu's fortifications but rather because Sargon knew that the Urartians anticipated him to attack through the Kel-i-šin pass.[24] Furthermore, the Assyrians were primarily lowland fighters with no experience in mountain warfare. By not entering Urartu through the mountain pass, Sargon avoided having to fight in terrain the Urartians were more experienced with.[11]

Sargon's decision was a costly one; on the longer route he had to cross several mountains with his entire army and this, combined with the greater distance, made the campaign take longer time than a direct attack would have. The lack of time forced Sargon to abandon his plan to fully conquer Urartu and take the kingdom's capital, Tushpa, because his campaign had to be completed before October so that the mountain passes did not become blocked by snow.[24]

Once Sargon reached the land of Gilzanu, near Lake Urmia, he made camp and began considering his next move. Sargon's bypassing of the Gerdesorah meant that the Urartian forces had to abandon their original defensive plan, quickly regrouping and constructing new fortifications to the west and south of Lake Urmia.[25] At this point, the Assyrians had been marching through difficult and unfamiliar terrain and though they had been granted supplies and waters by the recently subjugated Medes, they were exhausted. According to Sargon's own account, "their morale turned mutinous. I could give no ease to their weariness, no water to quench their thirst". When Rusa I arrived with his army to defend his country, Sargon's army refused to fight. Sargon, determined to not surrender or retreat, called upon his personal bodyguard and led them in a brutal and almost suicidal attack against the nearest portions of Rusa's army. As this portion of the Urartian army fled, the rest of the Assyrian army was inspired by Sargon personally leading the charge and followed their king into battle. The Urartians were defeated and retreated, being chased westwards by the Assyrians, far past Lake Urmia. Rusa fled into the mountains rather than rallying to defend his capital.[11]

Having defeated his enemy and fearing that his army may turn on him if he pursued Rusa into the mountains or pushed them further into Urartu, Sargon decided to march back to Assyria.[11] On their way home the Assyrians destroyed the Gerdesorah (which at that point was probably garrisoned only by a skeleton crew) and captured and plundered the city Musasir.[25] The official casus belli explicitly for the plunder of this holy city was that its ruler, Urzana, had betrayed the Assyrians but the real reasons were probably economical. The city's great temple, the temple of Haldi (the Urartian god of war), had been revered since the late 3rd millennium BC and had received gifts and donations for centuries. Sargon's plunder of the temples and palaces in the city resulted in the king securing, among other treasures, about ten tonnes of silver and over a tonne of gold.[20] According to Sargon's inscriptions, King Rusa committed suicide once he heard of the sack of Musasir, although there is some evidence for his continued presence.[11][26]

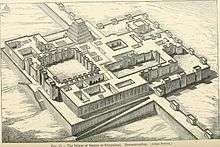

Construction of Dur-Sharrukin

In 713 BC, his finances bolstered by his successful campaigns, Sargon began the construction of Dur-Sharrukin (Akkadian: Dur-Šarru-kīn, meaning "Sargon's fortress"), intending it to be his new capital. Unlike the efforts of previous Assyrian kings to move the capital (such as Ashurnasirpal II's renovation of Kalhu centuries prior or Sennacherib's move to Nineveh after Sargon's death), Dur-Sharrukin was not the expansion of an existing city but the construction of an entirely new city. The location decided upon by Sargon, quite near Kalhu, was what Sargon perceived as the perfect site for the Assyrian Empire's center.[20]

The project was an enormous task and Sargon intended the new city to be his greatest achievement. The land the city was constructed on had previously been owned by villagers in the nearby village Maganubba and in foundation inscriptions from the city, Sargon himself proudly claims credit for recognizing the location as optimal and emphasizes that he paid the villagers in Maganubba the market rate for their lands. With a projected area of almost three square kilometres, the city was to be the largest city in Assyria and Sargon began irrigation projects to provide water for the massive amount of agriculture which would be required to sustain the city's inhabitants.[20] Sargon was highly involved in the construction project, constantly supervising it while also holding court at Kalhu and receiving and entertaining foreign envoys from countries such as Egypt or Kush.[11] In one letter to the governor of Kalhu, Sargon wrote the following:

The king’s word to the governor of Kalhu: 700 bales of straw and 700 bundles of reed, each bundle more than a donkey can carry, must arrive in Dur-Sharrukin by the first of the month Kislev. Should one day pass by, you will die.[11]

Though inspiration was taken from the layout of Kalhu, the plans of the two cities were not identical. While Kalhu had been renovated extensively by Ashurnasirpal II, it was still a settlement that had grown over time somewhat organically. Sargon's city was perfectly symmetrical, with no concern being taken for the landscape surrounding the construction site. Everything in the city; two gigentic platforms (one housing the royal arsenal, the other housing the temples and the palace), the fortified city wall and seven monumental city gates where constructed completely from scratch. The city gates were placed at regular intervals with no regard for the road networks which already existed in the empire.[20] Sargon's palace at Dur-Sharrukin was larger and more decorated than the palaces of all of his predecessors.[20] Reliefs adorning the walls within the palace depicted scenes of Sargon's conquests, especially the Urartu campaign and Sargon's sack of Musasir.[11]

Sargon's later campaigns varied in success. Sargon was successful in conquering the Kingdom of Ashdod in modern-day Israel in 711 BC and successfully incorporated the Syro-Hittite kingdoms of Gurgum (711 BC) and Kummuhhu (708 BC) into the Assyrian Empire. Sargon's 713 BC campaign in central Anatolia, aimed at conquering the small kingdom of Tabal and establishing it as an Assyrian province was successful, but the province was lost in 712 BC following a bloody rebellion, something which had never before happened in Assyrian history.[20]

Reconquest of Babylon

Sargon's greatest victory was his 710–709 BC defeat of his rival Marduk-apla-iddina II in Babylon.[20] Since his defeat in his first attempt to restore Assyrian authority in the south, Babylonia had represented a thorn in his side but he knew that he had to attempt another tactic than the straightforward method he had previously used.[11] When Sargon marched south in 710 BC, the administration of the empire and the supervision of his construction project was left in the hands of his son and crown prince, Sennacherib.[11] Sargon did not immediately march to Babylon, instead marching alongside the eastern bank of the river Tigris until he reached the city Dur-Athara, near a river the Assyrians called the Surappu. Dur-Athara had been fortified by Marduk-apla-iddina but was quickly taken by Sargon's forces and renamed Dur-Nabu with a new province, "Gambulu", proclaimed as composing the territory surrounding the city. Sargon spent some time at Dur-Nabu, sending his troops on expeditions to the east and south to make the people living there submit to his rule. In the lands surrounding a river called the Uknu, Sargon's forces defeated Aramean and Elamite soldiers, which would prevent these peoples aiding Marduk-apla-iddina.[27]

Sargon then turned to attack Babylon itself, marching his forces towards the city from the southeast.[11] Once Sargon had crossed the Tigris and one of the branches of the Euphrates and arrived at the city Dur-Ladinni, near Babylon, Marduk-apla-iddina became frightened, possibly because he either had little true support from the people and priesthood of Babylon or because most of his army had already been defeated at Dur-Athara.[27] Because he did not wish to fight the Assyrians, he left Babylon at night, carrying with him as much of the treasury and his personal royal furniture (including his throne) as his entourage could carry. These treasures were used by Marduk-apla-iddina in an attempt to gain asylum in Elam, offering them as a bribe to the Elamite king Shutur-Nahhunte II in order to be admitted entry into his country. Though the Elamite king accepted the treasures, Marduk-apla-iddina was not allowed to enter Elam due to fears of Assyrian retribution.[11][27]

Instead, Marduk-apla-iddina took up residence in the city Iqbi-Bel, but Sargon soon pursued him there and the city surrendered to him without the need for a battle. Marduk-apla-iddina then fled to his home city near the shores of the Persian Gulf, Dur-Jakin.[11][27] The city was fortified, a great ditch was dug surrounding its walls and the surrounding countryside was flooded through a canal dug from the Euphrates. Guarded by the flooded terrain, Marduk-apla-iddina set up his camp at some point outside the city walls, where they would soon be defeated by Sargon's army, which had crossed through the flooded terrain unimpeded. Marduk-apla-iddina fled into the city as the Assyrians began collecting spoils of war from his fallen soldiers.[28] After the battle, Sargon besieged Dur-Jakin but was unable to take the city. As the siege dragged on, negotiations were started and in 709 BC it was agreed that the city would surrender and tear down its exterior walls in exchange for Sargon sparing the life of Marduk-apla-iddina.[29]

Final years

After the Babylonian reconquest, Sargon was proclaimed King of Babylon by the citizens of the city and spent the next three years in Babylon, in Marduk-apla-iddina's palace,[27] receiving homage and gifts from rulers as far away from the heartland of his empire as Bahrain and Cyprus.[11][20] In 707 BC,[30] several Cypriote kingdoms were defeated by the Assyrian vassal state Tyre, with Assyrian aid. Through the campaign, which did not serve to establish Assyrian rule on the island, but just to aid their ally, the Assyrians gained detailed knowledge of Cyprus (which they called Adnana) for the first time in their history.[31] After the campaign had concluded, the Cypriotes, probably with the aid of an Assyrian stonemason sent by the royal court,[32] fashioned the Sargon Stele. The stele was not intended to serve as some permanent claim to rule the island, but rather as an ideological marker indicating the boundary of the Assyrian king's sphere of influence. The stele served to mark the incorporation of Cyprus into the "known world" (the Assyrians now having gained sufficient knowledge of the island) and since it had the king's image and words on it, served as representation of Sargon and a substitute for his presence.[31] Had the Assyrians wished to conquer Cyprus for themselves, they would have been unable to do so. They completely lacked a fleet.[33]

Sargon participated in the Babylonian New Year's festivals, dug a new canal from Borsippa to Babylon, and defeated a people called the Hamaranaeans which had been plundering caravans in the vicinity of the city Sippar.[27] While Sargon resided at Babylon, Sennacherib continued to act as regent in Kalhu, Sargon only returning to the Assyrian heartland when the court was moved to Dur-Sharrukin in 706 BC. Though the city was not yet completely finished, Sargon finally got to enjoy the capital which he had dreamt of building in his own honor, though he would not get to enjoy it for long.[11][20]

In 705 BC, Sargon returned to the rebellious province of Tabal, intending to once more turn it into an Assyrian province. As with his successful campaign against Babylonia, Sargon left Sennacherib in charge of the Assyrian heartland and personally led his army through Mesopotamia and into Anatolia.[11][20] Sargon, who apparently did not realize the true threat represented by a minor country such as Tabal (which had recently been strengthened through an alliance with the Cimmerians, a people which would return in later years to plague the Assyrians), charged at the enemy personally and met a violent end in battle,[34] to the shock of his army. His body could not be recovered by the soldiers and was lost to the enemy.[11][20]

Family and children

_faces_a_high-ranking_official%2C_possibly_Sennacherib_his_son_and_crown_prince._710-705_BCE._From_Khorsabad%2C_Iraq._The_British_Museum%2C_London.jpg)

Though Sargon's relation to his supposed father Tiglath-Pileser III and supposed older brother Shalmaneser V is not entirely certain, he is confidently known to have had a younger brother, Sîn-ahu-usur, who by 714 BC was in command of Sargon's royal cavalry guard and had his own residence at Dur-Sharrukin. If Sargon was the son of Tiglath-Pileser, his mother could possibly have been Tiglath-Pileser's first wife Iabâ.[12] Around the time of Tiglath-Pileser's rise to the throne, Sargon married a woman by the name Ra'īmâ, who was the mother of at least his first three children. He also had a second wife, Atalia, whose grave was discovered at Kalhu in the 1980s.[1] The known children of Sargon are:

- Two older sons (names unknown) of Sargon and Ra'īmâ, dead before Sennacherib was born.[1]

- Sennacherib (Akkadian: Sîn-ahhī-erība)[35] – son of Sargon and Ra'īmâ, Sargon's successor as King of Assyria 705–681 BC.[1]

- Ahat-abisha (Akkadian: Ahat-abiša)[36] – a daughter.[1] Was married off to Ambaris, the King of Tabal. When Ambaris was dethroned during Sargon's first 713 BC campaign in Tabal, Ahat-abisha was probably forced to return to Assyria.[36]

- At least two younger sons (names unknown).[1]

Character

Sargon II was a warrior king and conqueror who commanded his armies in person and dreamed of conquering the entire world, following in the footsteps of Sargon of Akkad. Sargon II used many of the most prestigious ancient Mesopotamian royal titles to signify his desire to reach this goal, such as "king of the universe" and "king of the four corners of the world". His power and greatness were expressed with titles such as "great king" and "mighty king". Sargon wanted to be perceived as a brave, omnipresent warlord always throwing himself into battle, describing himself in his inscriptions as a "brave warrior" and a "mighty hero".[37] The king sought to project an image of piety, justice, energy, intelligence and strength.[38]

Although Sargon's inscriptions contain acts of brutal retribution against Assyria's enemies, as the inscriptions of most Assyrian kings do, they do not contain any overt sadism (unlike the inscriptions of some other kings, such as Ashurnasirpal II). Sargon's brutal actions against his enemies should be understood in the context of the Assyrian worldview; since Sargon perceived himself as having been bestowed with the kingship by the gods, the gods approved his policies, and thus his wars were just. The enemies of Assyria were seen as peoples who did not respect the gods and they were thus treated and punished as criminals.[39] The support of the gods is reinforced in Sargon's own inscriptions, which (like those of other Assyrian kings) always begin with mentions of the gods.[40] There are situations in which Sargon showed mercy (and other Assyrian kings might not have), such as sparing the lives of the people who had rebelled against him in the Assyrian heartland early in his reign and sparing the life of his rival, Marduk-apla-iddina.[11][20] The most brutal atrocities described in Sargon's inscriptions do not necessarily reflect reality; though scribes would have been present during his campaigns, realism and accuracy were not as important as propaganda (serving both to reinforce the king's glory and to intimidate Assyria's other enemies).[39]

Though his exploits are likely exaggerated in his inscriptions, Sargon appears to have been a skilled strategist. The king had an extensive spy network, useful for administration and military activities, and employed well-trained scouts for reconnaissance when on campaign. Because most of the states bordering the Neo-Assyrian Empire were Sargon's enemies, targets for campaigns had to be picked wisely to avoid disaster.[41]

Unlike some "great conquerors" of history, such as Alexander the Great, Sargon was not a charismatic leader. His own troops appear to have feared him as much as his enemies, with the king threatening punishments, such as impalement and the slaughter of families, to ensure discipline and obedience. Since there exist no records of such punishment ever actually being carried out, it is likely that these were simply threats. His soldiers, familiar with these actions being carried out against Sargon's enemies, might have seen the threats as enough and not required actual examples to be made for obedience. The main incentive to continue serving in the Assyrian army was probably not fear, but rather the frequent spoils of war that could be taken after victories.[42]

Legacy

Archaeological discoveries

Though not as famous as Sargon of Akkad, who had become legendary even in Sargon II's time, the large amount of sources left behind from Sargon II's reign means that he is better known from historical sources than the Akkadian king.[43] Like all other Assyrian kings, Sargon went to great lengths to leave behind testimonies to his glory, striving to outdo the accomplishments of his predecessors, creating detailed annals and a vast amount of royal inscriptions and erecting stelae and monuments to commememorate his conquests and mark the borders of his empire.[44] Further sources for Sargon's time include the numerous clay tablets dating to his reign, including legal and administrative documents and personal letters. In total, 1,155–1,300 letters have been discovered from Sargon's time, though many of these are unrelated to the king himself.[45]

The rediscovery of Dur-Sharrukin was made by chance. The discoverer, French archaeologist and consul Paul-Émile Botta had originally been excavating a nearby site which did not give any immediate results (unknown to Botta, this site was the later and far grander capital Nineveh) and moved his excavation to the village of Khorsabad in 1843. There, Botta discovered the ruins of Sargon's ancient palace and its surroundings and excavated much of it together with another French archaeologist, Victor Place. Place excavated almost the entire palace as well as large parts of the surrounding town. Further excavations were made by Iraqi archaeologists in the 1990s. Though much what was excavated at Dur-Sharrukin was left at Khorsabad, reliefs and other artefacts have since been transported away and are today exhibited across the world, notably at the Louvre, the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago and the Iraq Museum.[19]

The site in Khorsabad suffered extensive damage during the Iraqi Civil War of 2014–2017, allegedly being looted by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant in the spring of 2015 and in October 2016, the site was damaged as Kurdish Peshmerga forces bulldozed and built large military posts on top of archaeological remains.[46]

Legacy and assessment by historians

Sargon's death in battle and the loss of his body was a tragedy to the Assyrians at the time and was perceived as an evil omen. To suffer this fate, it was believed that Sargon had somehow committed some form of sin which caused the gods to abandon him on the battlefield. Fearing the same fate would befall him, Sargon's heir Sennacherib abandoned Dur-Sharrukin immediately and moved the capital to Nineveh.[11] Sennacherib's reaction to the fate of his father was to distance himself from Sargon[47] and appears to have been denial, refusing to acknowledge and deal with what happened to him. Before he began any other major projects, one of Sennacherib's first actions as king was to rebuild a temple dedicated to the god Nergal, associated with death, disaster and war, at the city Tarbisu.[48]

Sennacherib was superstitious and spent much time asking his diviners what kind of sin Sargon could have committed to suffer the fate that he did.[10] A minor 704 BC[49] campaign (unmentioned in Sennacherib's later historical accounts), led by Sennacherib's magnates rather than the king himself, was sent against Tabal in order to avenge Sargon. Sennacherib spent a lot of time and effort to rid the empire of Sargon's imagery. Images which Sargon had created at the temple in Assur were made invisible through raising the level of the courtyard, Sargon's wife Atalia was buried hastily when she died without regard to the traditional burial practices (and in the same coffin as another woman, the queen of the previous king Tiglath-Pileser III), and Sargon is never mentioned in his inscriptions.[50] Sennacherib's treatment of his father's legacy suggests that the people of Assyria were quickly encouraged to forget that Sargon had ever ruled them.[11] After Sennacherib's reign, Sargon was sometimes mentioned as the ancestor of later kings. He is mentioned in the inscriptions of his grandson Esarhaddon (r. 681–669 BC),[51] his great-grandson Shamash-shum-ukin (r. 668–648 BC in Babylonia)[52] and his great-great-grandson Sinsharishkun (r. 627–612 BC).[53]

Prior to the rediscovery of Dur-Sharrukin in the 1840s, Sargon was an obscure figure in Assyriology. At the time, scholars of the Ancient Near East were dependent on classical authors and the Old Testament of the Bible. Though some Assyrian kings are mentioned in several places (and some appear very prominently), such as Sennacherib and Esarhaddon, Sargon is only mentioned once in the Bible.[54] Scholars were puzzled by the mention of the obscure Sargon and tended to identify him with one of the better known kings, either Shalmaneser V, Sennacherib or Esarhaddon. In 1845, Assyriologist Isidor Löwenstern was the first to suggest that the Sargon briefly mentioned in the Bible was the builder of Dur-Sharrukin, though he still believed this was the same king as Esarhaddon.[55] The exhibition of architecture excavated at Dur-Sharrukin and the translation of the inscriptions uncovered at the city in the 1860s substantiated the idea that Sargon was a king distinct from the others. In the Ninth Edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica (1886), Sargon had his own entry and by the turn of the century he was as accepted and recognized as his previously more well-known predecessors and successors.[56]

The modern image of Sargon derives from his own inscriptions from Dur-Sharrukin and the work of later Mesopotamian chroniclers. Today, Sargon is recognized as one of the Neo-Assyrian Empire's most important kings through his role in founding the Sargonid dynasty, which would rule Assyria until its fall roughly a century after his death. Through study of his greatest building project, Dur-Sharrukin, he has been seen as a patron of the arts and culture and he was a prolific builder of monuments and temples, both in Dur-Sharrukin and elsewhere. His successful military campaigns have cemented the king's legacy as a great military leader and tactician.[11]

Titles

Sargon's 707 BC stele from Cyprus accords the king the following titulature:

Sargon, the great king, the mighty king, king of the universe, king of Assyria, viceroy of Babylon, king of Sumer and Akkad, king of the four regions of the earth, favorite of the great gods, who go before me; Assur, Nabû and Marduk have intrusted to me an unrivaled kingdom and have caused my gracious name to attain unto highest renown.[57]

In an account of restoration work done to Ashurnasirpal II's palace in Kalhu (written before his victory over Marduk-apla-iddina II), Sargon uses the following longer titulature:

Sargon, prefect of Enlil, priest of Assur, elect of Anu and Enlil, the mighty king, king of the universe, king of Assyria, king of the four quarters of the world, favorite of the great gods, rightful ruler, whom Assur and Marduk have called, and whose name they have caused to attain unto the highest renown; mighty hero, clothed in terror, who sends forth his weapon to bring low the foe; brave warrior, since the day of whose accession to rulership, there has been no prince equal to him, who has been without conqueror or rival; who has brought under his sway all lands from the rising to the setting sun and has assumed the rulership of the subjects of Enlil; warlike leader, to whom Nudimmud has granted the greatest might, whose hand has drawn a sword which cannot be withstood; exalted prince, who came face to face with Humbanigash, king of Elam, in the outskirts of Dêr and defeated him; subduer of the land of Judah, which lies far away; who carried off the people of Hamath, whose hands captured Yau-bi'di, their king; who repulsed the people of Kakmê, wicked enemies; who set in order the disordered Mannean tribes; who gladdened the heart of his land; who extended the border of Assyria; painstaking ruler; snare of the faithless; whose hand captured Pisiris, king of Hatti, and set his official over Carchemish, his capital; who carried off the people of Shinuhtu, belonging to Kiakki, king of Tabal, and brought them to Assur, his capital; who placed his yoke on the land of Muski; who conquered the Manneans, Karallu and Paddiri; who avenged his land; who overthrew the distant Medes as far as the rising sun.[58]

See also

References

- Melville 2016, p. 56.

- Bertin 1891, p. 49.

- Elayi 2017, p. 13.

- Elayi 2017, p. 14.

- Healy 1991, p. 17.

- Parker 2011.

- Mark 2014a.

- Elayi 2017, p. 8, 26.

- Elayi 2017, p. 27.

- Brinkman 1973, p. 91.

- Mark 2014b.

- Elayi 2017, p. 28.

- Ahmed 2018, p. 63.

- Elayi 2017, p. 26.

- Hurowitz 2010, p. 93.

- Elayi 2017, p. 12.

- Elayi 2017, p. 15.

- Elayi 2017, p. 29.

- Elayi 2017, p. 7.

- Radner 2012.

- Jakubiak 2004, p. 192.

- Jakubiak 2004, p. 191.

- Jakubiak 2004, p. 194.

- Jakubiak 2004, p. 197.

- Jakubiak 2004, p. 198.

- Elayi 2017, p. 143.

- Van Der Spek 1977, p. 57.

- Van Der Spek 1977, p. 60.

- Van Der Spek 1977, p. 62.

- Radner 2010, p. 434.

- Radner 2010, p. 440.

- Radner 2010, p. 432.

- Radner 2010, p. 438.

- Luckenbill 1924, p. 9.

- Harmanşah 2013, p. 120.

- Dubovský 2006, pp. 141–142.

- Elayi 2017, p. 16.

- Elayi 2017, p. 23.

- Elayi 2017, p. 18.

- Elayi 2017, p. 21.

- Elayi 2017, p. 19.

- Elayi 2017, p. 20.

- Elayi 2017, p. 4.

- Elayi 2017, p. 5.

- Elayi 2017, p. 6.

- Romey 2016.

- Frahm 2008, p. 15.

- Frahm 2014, p. 202.

- Frahm 2003, p. 130.

- Frahm 2014, p. 203.

- Luckenbill 1927, pp. 224–226.

- Karlsson 2017, p. 10.

- Luckenbill 1927, p. 413.

- Holloway 2003, p. 68.

- Holloway 2003, pp. 69–70.

- Holloway 2003, p. 71.

- Luckenbill 1927, p. 101.

- Luckenbill 1927, pp. 71–72.

Cited bibliography

- Ahmed, Sami Said (2018). Southern Mesopotamia in the time of Ashurbanipal. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 978-3111033587.

- Bertin, G. (1891). "Babylonian Chronology and History". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 5: 1–52.

- Brinkman, J. A. (1973). "Sennacherib's Babylonian Problem: An Interpretation". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 25 (2): 89–95. doi:10.2307/1359421. JSTOR 1359421.

- Dubovský, Peter (2006). Hezekiah and the Assyrian Spies: Reconstruction of the Neo-Assyrian Intelligence Services and Its Significance for 2 Kings 18-19. Gregorian & Biblical Press. ISBN 978-8876533525.

- Elayi, Josette (2017). Sargon II, King of Assyria. SBL Press. ISBN 978-1628371772.

- Frahm, Eckart (2003). "New sources for Sennacherib's "first campaign"". Isimu. 6: 129–164.

- Frahm, Eckart (2008). "The Great City: Nineveh in the Age of Sennacherib". Journal of the Canadian Society for Mesopotamian Studies. 3: 13–20.

- Frahm, Eckart (2014). "Family Matters: Psychohistorical Reflections on Sennacherib and His Times". In Kalimi, Isaac; Richardson, Seth (eds.). Sennacherib at the Gates of Jerusalem: Story, History and Historiography. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-9004265615.

- Harmanşah, Ömür (2013). Cities and the Shaping of Memory in the Ancient Near East. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107533745.

- Healy, Mark (1991). The Ancient Assyrians. Osprey. ISBN 1-85532-163-7.

- Holloway, Steven W. (2003). "The Quest for Sargon, Pul and Tiglath-Pileser in the Nineteenth Century". In Chavalas, Mark W.; Younger, Jr, K. Lawson (eds.). Mesopotamia and the Bible. A&C Black. ISBN 978-0567082312.

- Hurowitz, Victor Avigdor (2010). "Name Midrashim and Word Plays on Names in Akkadian Historical Writings". In Horowitz, Wayne; Gabbay, Uri; Vukosavovic, Filip (eds.). A woman of valor: Jerusalem Ancient Near Eastern Studies in Honor of Joan Goodnick Westenholz. CSIC Press. ISBN 978-8400091330.

- Jakubiak, Krzysztof (2004). "Some remarks on Sargon II's eighth campaign of 714 BC". Iranica Antiqua. 39: 191–202. doi:10.2143/IA.39.0.503895.

- Karlsson, Mattias (2017). "Assyrian Royal Titulary in Babylonia". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Luckenbill, Daniel David (1924). The Annals of Sennacherib (PDF). University of Chicago Press.

- Luckenbill, Daniel David (1927). Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylonia Volume 2: Historical Records of Assyria From Sargon to the End. University of Chicago Press.

- Melville, Sarah C. (2016). The Campaigns of Sargon II, King of Assyria, 721–705 B.C. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806154039.

- Parker, Bradley J. (2011). "The Construction and Performance of Kingship in the Neo-Assyrian Empire". Journal of Anthropological Research. 67 (3): 357–386. doi:10.3998/jar.0521004.0067.303. JSTOR 41303323.

- Radner, Karen (2010). "The stele of Sargon II of Assyria at Kition: A focus for an emerging Cypriot identity?". In Rollinger, Robert; Gufler, Birgit; Lang, Martin; Madreiter, Irene (eds.). Interkulturalität in der Alten Welt: Vorderasien, Hellas, Ägypten und die vielfältigen Ebenen des Kontakts. Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3447061711.

- Van Der Spek, R. (1977). "The struggle of king Sargon II of Assyria against the Chaldaean Merodach-Baladan (710-707 B.C.)". JEOL. 25: 56–66.

Cited web sources

- Mark, Joshua J. (2014). "Sargonid Dynasty". Ancient History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- Mark, Joshua J. (2014). "Sargon II". Ancient History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- Radner, Karen (2012). "Sargon II, king of Assyria (721-705 BC)". Assyrian empire builders. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

Cited news sources

- Romey, Kristin (10 November 2016). "Iconic Ancient Sites Ravaged in ISIS's Last Stand in Iraq". National Geographic. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sargon II. |

- Daniel David Luckenbill's Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylonia Volume 2: Historical Records of Assyria From Sargon to the End, containing translations of a large number of Sargon II's inscriptions.

Sargon II Born: c. 762 BC Died: 705 BC | ||

| Preceded by Shalmaneser V |

King of Assyria 722 – 705 BC |

Succeeded by Sennacherib |

| Preceded by Marduk-apla-iddina II |

King of Babylon 710 – 705 BC | |