Ashur-rim-nisheshu

Aššur-rā’im-nišēšu, inscribed mdaš-šur-ÁG-UN.MEŠ-šu, meaning “(the god) Aššur loves his people,”[1] was ruler of Assyria, or išši’ak Aššur, “vice-regent of Aššur,” written in Sumerian: PA.TE.SI (=ÉNSI), c. 1408–1401 BC or c. 1398–1391 BC (short chronology), the 70th to be listed on the Assyrian King List. He is best known for his reconstruction of the inner city wall of Aššur.

| Ashur-rim-nisheshu | |

|---|---|

| King of Assyria | |

| King of the Old Assyrian Empire | |

| Reign | 1398–1391 BC |

| Predecessor | Ashur-bel-nisheshu |

| Successor | Ashur-nadin-ahhe II |

| Issue | Ashur-nadin-ahhe II |

| Father | Ashur-bel-nisheshu |

Biography

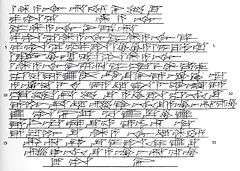

All three extant Assyrian Kinglists[i 2][i 3][i 4] give his filiation as “son of Aššur-bēl-nišēšu," the monarch who immediately preceded him, but this is contradicted by the sole extant contemporary inscription, a cone giving a dedicatory inscription for the reconstruction of the wall of the inner city of Aššur, which gives his father as Aššur-nērārī II (written phonetically on the third line of the illustration),[2] the same as his predecessor who was presumably therefore his brother. With Ber-nādin-aḫḫe, another son of Aššur-nērārī who was given the title "supreme judge," it seems he may have been the third of Aššur-nērārī's sons to rule.[3]

The cone identifies the previous restorers as Kikkia (c. 2000 BC), Ikunum (1867–1860 BC), Sargon I (1859 BC – ?), Puzur-Aššur II, and Aššur-nārāri I (1547–1522 BC) the son of Ishme-Dagan II (1579–1562 BC).[4] The reference to Kikkia's original fortification of the city is repeated in one of the later king's, Salmānu-ašarēd III, own inscriptions.[5] It was recovered from an old adobe wall three meters from the northern edge of the ziggurat.[6]

He was succeeded by his son, Aššur-nadin-aḫḫē II.

Inscriptions

- Cone VAT? 2764, first published KAH 1 no. 63 (1911).

- Khorsabad Kinglist iii 7.

- SDAS Kinglist iii 1.

- Nassouhi Kinglist iii 11.

References

- K. Radner (1998). The Prosopography of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, Volume 1, Part I: A. The Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project. p. 209.

- J. A. Brinkman (1973). "Comments on the Nasouhi Kinglist and the Assyrian Kinglist Tradition". Orientalia. 42: 312.

- B. Newgrosh (1999). "The Chronology of Ancient Assyria Re-assessed". JAVF. 8: 80.

- A. K. Grayson (1972). Assyrian Royal Inscriptions, Volume I. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz. pp. 39–40.

- Hildegard Lewy (1966). The Cambridge Ancient History: Assyria c.2600-1816 B.C. p. 21.

- L. Messerschmidt (1911). Keilschrifttexte aus Assur Historischen Inhalts, Erstes Heft. VDOG. p. xii.

| Preceded by Aššur-bēl-nišēšu |

King of Assyria 1398–1391 BC |

Succeeded by Aššur-nadin-aḫḫē II |