Quimbaya civilization

The Quimbaya civilization (/kɪmbaɪa/) was a Pre-Columbian culture of Colombia, noted for their gold work characterized by technical accuracy and detailed designs. The majority of the gold work is made in tumbaga alloy, with 30% copper, which imparts meaningful color tonalities to the pieces.

_01.jpg)

History

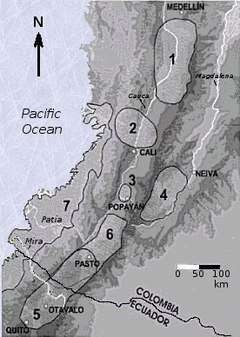

The Quimbaya inhabited the areas corresponding to the modern departments of Quindío, Caldas and Risaralda in Colombia, around the valley of the Cauca River. There is no clear data about when they were initially established; the current best guess is around the 1st century BCE.

The Quimbaya people reached their zenith during the 4th to 7th century CE period known as The Quimbaya Classic. The culture's the most emblematic piece comes from this period, a form of poporo known as the Poporo Quimbaya, on exhibit at the Bogotá Gold Museum. The most frequent designs in the art pieces are anthropomorphic, depicting men and women sitting with closed eyes and placid expression, as well as many fruits and forms of poporos.

Most of the retrieved items are part of funeral offerings, found inside sarcophagi made of hollow trunks. The gold represented a sacred metal and the passport for the afterlife. Around the 10th century the Quimbaya culture disappeared entirely due to unknown circumstances; studies of the archeological items point to an advanced cultural development and the political structure of a cacicazgo with separated groups dedicated to pottery, religion, trade, gold work and war.

Economy

Living in the temperate tropical climate of the coffee belt, they were able to cultivate a wide variety of products: corn and cassava, as a food base, avocados, guava. They were also nourished by fishing and hunting, and they were excellent farmers, with what the land gave them.

They were also intense hunters. The hunt provided them with rabbit and deer meat in abundance, but also, as far as is known, they hunted opossums, tapirs, armadillos, foxes and peccaries, among other animals whose remains have been found.

Mining was mainly gold. They developed advanced metallurgy techniques to process gold in a way that is full of aesthetics and fine finishes. The name "quimbaya" has become a traditional generic term to refer to many of the productions and objects found in this geographical area, even if they do not come rigorously from the same ethnic group and come from different epochs in time.

Quimbaya technical skill extended beyond the production of goldsmith's pieces, including in the manufacture of oil for lighting, and in textiles, although given the poor geological conditions necessary for their preservation, few examples of textiles have survived. The manufacture of cotton blankets was, in fact, their main industry.

As merchants, they exchanged their pieces of metalwork, blankets, textiles and gold, with towns in neighboring regions and beyond. They also produced and traded salt, extracted from the rivers though a technique involving boiling river water using fire and lava.

Culture and customs

It is discussed if the Quimbaya practiced ritual cannibalism with their war enemies, in festivities or very special celebrations. This cannibalism would have symbolic meanings related to the defeat and revenge of its enemies or to the appropriation of the spirit of the person. However, in the case of the Quimbaya, the chronicles referred to in cannibalism are based on a single testimony about two alleged cases. They displayed human heads as trophies hanging from reeds in the plaza. During the conquest they intensified this practice to instill fear in the conquerors.

They paid much attention to their funeral practices, and the constructions of Quimbaya tombs bear witness to this affirmation since, in truth, they elaborated an enormous variety of different tombs according to the specifications of each funeral, in which the offerings that would accompany were always included. The deceased carried these on his way to the next life, including food and weapons to make it easier. In the tombs they also buried most of the pre-Columbian gold objects, personal elements of the dead and some other sacred elements. They believed that all bodies would be resurrected.

One of the most famous activities he has done to the Quimbaya is his luxurious goldsmith shop, which enjoys an incredible beauty as well as a perfect technique. They developed metallurgy systems to combine copper with gold that was not abundant in their region (unlike other areas of the country). This combination of gold and copper, called "tumbaga", would not detract from the attractiveness, brightness and durability of its magnificent pieces, of a spectacular vivacity. One of them, very popular, is the famous poporos. His goldsmithing is one of the most important in America given the exquisite beauty of the pieces expressed by very well developed metallurgical methods.

Its culture the way to melt the gold to obtain the exact grade of gold and copper to maintain a high purity, it is still unknown how such quality was achieved since they would need kilns that would reach a thousand degrees Celsius to melt these pieces.

Another of the mysteries of the Quimbaya Culture are the Quimbaya artifacts, formerly called "Pájaros del Otún", since the former was found near the banks of the Otún River in the province of Risaralda.

Engravings and petroglyphs of the Quimbayas can be found in the Natural Park of Las Piedras Marcadas, also known as La Marcada. They are located in the path Alto del Toro in the municipality of Dosquebradas Risaralda (Colombia). The stones are a mystery since no one knows exactly their antiquity or its true meaning. They are granitic stones of great hardness and onto their surface is carved spirals, stars, constellations, planets and other strange symbols; it may be some message from the gods that was left for posterity on the hard rock. The Park of the Marked Stones is one of the most unknown and despised parks by the scholars of the Colombian tribes, more interested in the goldsmith and clay works than in the lithic art. Others have related the marks with constellations and even they are related to the Quimbaya artifacts, and their mysterious origin; It is not really known why some were found on the banks of the Otún River when others have been found on the banks of the Cauca or the Magdalena.

Gallery

_MET_DT1262.jpg) Lime container (poporo); 1st–7th century; gold; height: 22.9, width: 13.3 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City, New York)

Lime container (poporo); 1st–7th century; gold; height: 22.9, width: 13.3 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City, New York) Anthropomorphic pendant; 5th–10th century; gold; height: 4.4 cm, width: 3.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City, New York)

Anthropomorphic pendant; 5th–10th century; gold; height: 4.4 cm, width: 3.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City, New York) Vessel in shape of a figure; 9th–14th century; ceramic; height: 23.1 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City, New York)

Vessel in shape of a figure; 9th–14th century; ceramic; height: 23.1 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City, New York) Jar decorated with geometric patterns; 9th–14th century; painted ceramic; height: 23.8 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City, New York)

Jar decorated with geometric patterns; 9th–14th century; painted ceramic; height: 23.8 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City, New York) Seated figure; 13th–15th century; ceramic: height: 22.9, width: 21 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City, New York)

Seated figure; 13th–15th century; ceramic: height: 22.9, width: 21 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City, New York) Ornament; 13th–16th century; hammered gold; overall: 4.45 x 6.35 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City, New York)

Ornament; 13th–16th century; hammered gold; overall: 4.45 x 6.35 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City, New York) Nose ring, a wide-spread type of jewel in the Pre-Columbian period of Colombia; before 1550; gold; overall: 1.8 x 2.2 cm; Cleveland Museum of Art (Cleveland, Ohio)

Nose ring, a wide-spread type of jewel in the Pre-Columbian period of Colombia; before 1550; gold; overall: 1.8 x 2.2 cm; Cleveland Museum of Art (Cleveland, Ohio)

See also

Indigenous peoples in Colombia

- Calima culture

- Spanish Empire

- Malagana treasure

- History of Colombia

- Population history of American indigenous peoples

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Quimbaya culture. |

- Quimbaya artwork, National Museum of the American Indian

- The Art of Precolumbian Gold: The Jan Mitchell Collection, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Quimbaya civilization