Pu'er tea

Pu'er or pu-erh[1] is a variety of fermented tea traditionally produced in Yunnan Province, China. In the context of traditional Chinese tea production terminology, fermentation refers to microbial fermentation (called 'wet piling'), and is typically applied after the tea leaves have been sufficiently dried and rolled.[2] As the tea undergoes controlled microbial fermentation, it also continues to oxidize, which is also controlled, until the desired flavors are reached. This process produces tea known as 黑茶 hēichá (lit. 'black tea') (which is different from the English-language black tea that is called 红茶 hóngchá (lit. 'red tea') in Chinese). Pu'er falls under a larger category of fermented teas commonly translated as dark teas.

| Pu'er tea | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Xiaguan Te Ji (special grade) raw tuocha from 2004 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 普洱茶 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

Two main styles of pu'er production exist: a traditional, longer production process known as shēng (raw) pu'er and a modern, accelerated production process known as shóu (ripe) pu'er. Pu'er traditionally begins with a raw product called "rough" (máo) chá (毛茶, lit. fuzzy/furry tea) and can be sold in this form or pressed into a number of shapes and sold as "shēng chá (生茶, lit. raw tea). Both of these forms then undergo the complex process of gradual fermentation and maturation with time. The wòduī (渥堆) fermentation process developed in 1973 by the Kunming Tea Factory[3][4] created a new type of pu'er tea. This process involves an accelerated fermentation into shóu (or shú) chá (熟茶, lit. ripe tea) that is then stored loose or pressed into various shapes. The fermentation process was adopted at the Menghai Tea Factory shortly after and technically developed there.[5] The legitimacy of shóu chá is disputed by some traditionalists when compared to the traditionally, longer-aged teas, such as shēng chá. All types of pu'er can be stored to mature (in non-airtight containers) before consumption, which is why it is standard to label them, moreso than most other types of tea, with the year and region of production.

The flavour and health benefits of Pu’er tea are related in part to its content of polyphenolic anti-oxidant molecules. In particular, theaflavin which is particular to highly oxidized black teas such as pu’er, and has a complex 3D self-stabilising structure that raises its radical scavenging ability.[6]

Name

Pu'er is the pinyin romanization of the Mandarin pronunciation of Chinese 普洱. Pu-erh is a variant of the Wade-Giles romanization (properly p‘u-êrh) of the same name. The town of Pu'er and its surrounding county derive from the tea, rather than vice versa,[7][8] but the area is now sometimes considered the appellation for pu'er proper.

History

Darkening tea leaves to trade with ethnic groups at the borders has a long history in China. These crude teas were of various origins and were meant to be low cost.[9] Darkened tea, or hēichá, is still the major beverage for the ethnic groups in the southwestern borders and, until the early 1990s, was the third major tea category produced by China mainly for this market segment.[7]

There had been no standardized processing for the darkening of hēichá until the postwar years in the 1950s where there was a sudden surge in demand in Hong Kong, perhaps because of the concentration of refugees from the mainland. In the 1970s the improved process was taken back to Yunnan for further development, which has resulted in the various production styles variously referred to as wòduī today.[4][10] This new process produced a finished product in a matter of months that many thought tasted similar to teas aged naturally for 10–15 years and so this period saw a demand-driven boom in the production of hēichá by the artificial ripening method.

In recent decades, demand has come full circle and it has become more common again for hēichá, including pu'er, to be sold as the raw product without the artificial accelerated fermentation process.

Pu'er tea processing, although straightforward, is complicated by the fact that the tea itself falls into two distinct categories: the "raw" Sheng Cha and the "ripe" Shu Chá. All types of pu'er tea are created from máochá (毛茶), a mostly unoxidized green tea processed from Camellia sinensis var. assamica, which is the large leaf type of Chinese tea found in the mountains of southern and western Yunnan (in contrast to the small leaf type of tea used for typical green, oolong, black, and yellow teas found in the other parts of China).

Maocha can be sold directly to market as loose leaf tea, compressed to produce "raw" shēngchá, naturally aged and matured for several years before being compressed to also produce "raw" shēngchá or undergo Wo Dui ripening for several months prior to being compressed to produce "ripe" shóuchá. While unaged and unprocessed, Máochá pǔ'ěr is similar to green tea. Two subtle differences worth noting are that pǔ'ěr is not produced from the small-leaf Chinese varietal but the broad-leaf varietal mostly found in the southern Chinese provinces and India. The second is that pǔ'ěr leaves are picked as one bud and 3-4 leaves whilst green tea is picked as one bud and 1-2 leaves. This means that older leaves contribute to the qualities of pǔ'ěr tea.

Ripened or aged raw pǔ'ěr has occasionally been mistakenly categorized as a subcategory of black tea due to the dark red color of its leaves and liquor. However, pǔ'ěr in both its ripened and aged forms has undergone secondary oxidization and fermentation caused both by organisms growing in the tea and free-radical oxidation, thus making it a unique type of tea. This divergence in production style not only makes the flavor and texture of pu'er tea different but also results in a rather different chemical makeup of the resulting brewed liquor.

The fermented dark tea, hēichá (黑茶), is one of the six classes of tea in China, and pǔ'ěr is classified as a dark tea (defined as fermented), something which is resented by some who argue for a separate category for pǔ'ěr tea.[11] As of 2008, only the large-leaf variety from Yunnan can be called a pǔ'ěr.

Processing

Pu'er is typically made through two steps. First, all leaves must be roughly processed into maocha to stop oxidation. From there it may be further processed by fermentation, or directly packaged. Summarising the steps:[3]:207

- Maocha: Killing Green (杀青) -- Rolling (揉捻) -- Sun Drying (晒干)

- green/raw (生普, sheng cha)

- dark/ripe (熟普, shu cha): -- Piling(渥堆))-- Drying(干燥))

Both sheng and ripe pu'er can be shaped into cakes or bricks and aged with time.

Maocha or rough tea

The intent of the maocha stage (青毛茶 or 毛茶; literally, "light green rough tea" or "rough tea" respectively) is to dry the leaves and keep them from spoiling. It involves minimal processing and there is no fermentation involved.

The first step in making raw or ripened pu'er is picking appropriate tender leaves. Plucked leaves are handled gingerly to prevent bruising and unwanted oxidation. It is optional to wilt/wither the leaves after picking and it depends on the tea processor, as drying occurs at various stages of processing.[3] If so, the leaves would be spread out in the sun, weather permitting, or a ventilated space to wilt and remove some of the water content.[12] On overcast or rainy days, the leaves will be wilted by light heating, a slight difference in processing that will affect the quality of the resulting maocha and pu'er.

.jpg)

The leaves are then dry-roasted using a large wok in a process called "killing the green" (殺青; pinyin: shā qīng), which arrests most enzyme activity in the leaf and prevents full oxidation.[3]:207 After pan-roasting, the leaves are rolled, rubbed, and shaped into strands through several steps to lightly bruise the tea and then left to dry in the sun. Unlike green tea produced in China which is dried with hot air after the pan-frying stage to completely kill enzyme activity, leaves used in the production of pu'er are not air-dried after pan-roasting, which leaves a small amount of enzymes which contribute a minor amount of oxidation to the leaves during sun-drying. The bruising of the tea is also important in helping this minimal oxidation to occur, and both of these steps are significant in contributing to the unique characteristics of pu'er tea.

Once dry, maocha can be sent directly to the factory to be pressed into raw pu'er, or to undergo further processing to make fermented or ripened pu'er.[3]:208 Sometimes Mao Cha is sold directly as loose-leaf "raw" Sheng Cha or it can be matured in loose-leaf form, requiring only two to three years due to the faster rate of natural fermentation in an uncompressed state. This tea is then pressed into numerous shapes and sold as a more matured "raw" Sheng Cha.

Ripe pu'er

"Ripened" Shu Cha (熟茶) tea is pressed maocha that has been specially processed to imitate aged "raw" Sheng Cha tea. Although it is also known in English as cooked pu'er, the process does not actually employ cooking to imitate the aging process. The term may be due to inaccurate translation, as shóu (熟) means both "fully cooked" and "fully ripened".

The process used to convert máochá into ripened pu'er manipulates conditions to approximate the result of the aging process by prolonged bacterial and fungal fermentation in a warm humid environment under controlled conditions, a technique called Wò Duī (渥堆, "wet piling" in English), which involves piling, dampening, and turning the tea leaves in a manner much akin to composting.[4]

The piling, wetting, and mixing of the piled máochá ensures even fermentation. The bacterial and fungal cultures found in the fermenting piles were found to vary widely from factory to factory throughout Yunnan, consisting of multiple strains of Aspergillus spp., Penicillium spp., yeasts, and a wide range of other microflora. Control over the multiple variables in the ripening process, particularly humidity and the growth of Aspergillus spp., is key in producing ripened pu'er of high quality.[13][14] Poor control in fermentation/oxidation process can result in bad ripened pu'er, characterized by badly decomposed leaves and an aroma and texture reminiscent of compost. The ripening process typically takes between 45 and 60 days on average.

The Wò Duī process was first developed in 1973 by Menghai Tea Factory and Kunming Tea Factory[4] to imitate the flavor and color of aged raw pu'er, and was an adaptation of wet storage techniques used by merchants to artificially simulate ageing of their teas. Mass production of ripened pu'er began in 1975. It can be consumed without further aging, or it can be stored further to "air out" some of the less savory flavors and aromas acquired during fermentation. The tea is sold both in flattened and loose form. Some tea collectors believe "ripened" Shu Cha should not be aged for more than a decade.

Wet pile fermented pu'er has higher levels of caffeine and much higher levels of gallic acid compared with traditionally aged raw pu'er. Additionally, traditionally aged pu'er has higher levels of the antioxidant and carcinogen-trapping epigallocatechin gallate as well as (+)-catechin, (–)-epicatechin, (–)-epigallocatechin, gallocatechin gallate, and epicatechin gallate than wet pile fermented pu'er. Finally, wet pile fermented puer has much lower total levels for all catechins than traditional pu'er and other teas except for black tea which also has low total catechins.[15]

Pressing

To produce pu'er, many additional steps are needed prior to the actual pressing of the tea. First, a specific quantity of dry máochá or ripened tea leaves pertaining to the final weight of the bingcha is weighed out. The dry tea is then lightly steamed in perforated cans to soften and make it more tacky. This will allow it to hold together and not crumble during compression. A ticket, called a "nèi fēi" (内飞) or additional adornments, such as colored ribbons, are placed on or in the midst of the leaves and inverted into a cloth bag or wrapped in cloth. The pouch of tea is gathered inside the cloth bag and wrung into a ball, with the extra cloth tied or coiled around itself. This coil or knot is what produces the dimpled indentation at the reverse side of a tea cake when pressed. Depending on the shape of the pu'er being produced, a cotton bag may or may not be used. For instance, brick or square teas often are not compressed using bags.[16]

Pressing can be done by:

- A press. In the past, hand lever presses were used, but were largely superseded by hydraulic presses. The press forces the tea into a metal form that is occasionally decorated with a motif in sunken-relief. Due to its efficiency, this method is used to make almost all forms of pressed pu'er. Tea can be pressed either with or without it being bagged, with the latter done by using a metal mould. Tightly compressed bǐng, formed directly into a mold without bags using this method are known as tié bǐng (鐵餅, literally "iron cake/puck") due to its density and hardness. The taste of densely compressed raw pu'er is believed to benefit from careful aging for up to several decades.

- A large heavy stone, carved into the shape of a short cylinder with a handle, simply weighs down a bag of tea on a wooden board. The tension from the bag and the weight of the stone together give the tea its rounded and sometimes non-uniform edge. This method of pressing is often referred to as: "hand" or "stone-pressing", and is how many artisanal pu'er bǐng are still manufactured.

Pressed pu'er is removed from the cloth bag and placed on latticed shelves, where they are allowed to air dry, which may take several weeks or months, depending on the wetness of the pressed cakes.[12] The pu'er cakes are then individually wrapped by hand, and packed.

Fermentation

Pu'er is a microbially fermented tea obtained through the action of molds, bacteria and yeasts on the harvested leaves of the tea plant. It is thus truly a fermented tea, whereas teas known in the west as black teas (known in China as Red teas) have only undergone large-scale oxidation through naturally occurring tea plant enzymes. Mislabelling the oxidation process as fermentation and thus naming black teas, such as Assam, Darjeeling or Keemun, as fermented teas has long been a source of confusion. Only tea such as pu'er, that has undergone microbial processing, can correctly be called a fermented tea.[17]

Pu'er undergoes what is known as a solid-state fermentation where water activity is low to negligible. Both endo-oxidation (enzymes derived from the tea-leaves themselves) and exo-oxidation (microbial catalysed) of tea polyphenols occurs. The microbes are also responsible for metabolising the carbohydrates and amino acids present in the tea leaves.[17][18][19] Although the microbes responsible have proved highly variable from region to region and even factory to factory, the key organism found and responsible for almost all pu'er fermentation has been identified in numerous studies as Aspergillus niger, with some highlighting the possibility of ochratoxins produced by the metabolism of some strains of A.niger having a potentially harmful effect through consumption of pu'er tea.[20][21][22][13] This notion has recently been refuted through a systematic chromosome analysis of the species attributed to many East Asian fermentations, including those that involve pu'er, where the authors have reclassified the organisms involved as Aspergillus luchuensis.[23] It is apparent that this species does not have the gene sequence for coding ochratoxin and thus pu'er tea should be considered safe for human consumption.[24]

Classification

Aside from vintage year, pu'er tea can be classified in a variety of ways: by shape, processing method, region, cultivation, grade, and season.

Shape

Pu'er is compressed into a variety of shapes. Other lesser seen forms include: stacked "melon pagodas", pillars, calabashes, yuanbao, and small tea bricks (2–5 cm in width). Pu'er is also compressed into the hollow centers of [bamboo]stems or packed and bound into a ball inside the peel of various citrus fruits.

| Image | Common name | Chinese characters | Pinyin | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | T | ||||

|

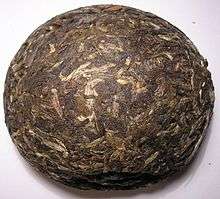

Bing, Beeng, Cake, or Disc | 饼茶 | 餅茶 | Bǐngchá | A round, flat, disc or puck-shaped tea, the size ranges from as small as 100g to as large as 5 kg or more, with 357g, 400g, and 500g being the most common. Depending on the pressing method, the edge of the disk can be rounded or perpendicular. It is also commonly known as Qīzí bǐngchá (七子餅茶, Chi Tsu Ping Cha, Chi Tse Beeng Cha, literally "seven units cake tea") because seven of the bing are packaged together at a time for sale or transport. |

|

Tuocha, Bowl, or Nest | 沱茶 | 沱茶 | Tuóchá | A convex knob-shaped tea, its size ranges from 3g to 3 kg or more, with 100g, 250g and 500g being the most common. The name for tuocha is believed to have originated from the round, top-like shape of the pressed tea or from the old tea shipping and trading route of the Tuo River.[25] In ancient times, tuocha cakes may have had holes punched through the center so they could be tied together on a rope for easy transport. |

|

Brick | 砖茶 | 磚茶 | Zhuānchá | A thick rectangular block of tea, usually in 100g, 250g, 500g and 1000g sizes; Zhuancha bricks are the traditional shape used for ease of transport along the ancient tea route by horse caravans. |

|

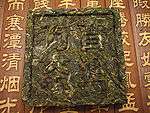

Square | 方茶 | 方茶 | Fāngchá | A flat square of tea, usually in 100g or 200g sizes. Characters are often pressed into the square, as in the example illustrated. |

|

Mushroom | 紧茶 | 緊茶 | Jǐnchá | Literally meaning "tight tea," the tea is shaped much like a 250g to 300g túocha, but with a stem rather than a convex hollow. This makes them quite similar in form to a mushroom. Pu'er tea of this shape is generally produced for Tibetan consumption. |

|

Dragon Pearl | 龙珠 | 龍珠 | Lóngzhū | A small ball-shaped or rolled tea, convenient for a single serving. Generally balls contain between 5 and 10 grams of compressed material. The practice is also common among Yunnan black tea and scented green teas. |

|

Gold Melon | 金瓜 | 金瓜 | Jīnguā | Its shape is similar to tuóchá, but larger in size, with a much thicker body decorated with pumpkin-like ribbing. This shape was created for the "Tribute tea"(貢茶) made expressly for the Qing dynasty emperors from the best tea leaves of Yiwu Mountain. Larger specimens of this shape are sometimes called "human-head tea" (人頭茶), due in part to its size and shape, and because in the past it was often presented in court in a similar manner to severed heads of enemies or criminals. |

Process and oxidation

Pu'er teas are often collectively classified in Western tea markets as post-fermentation, and in Eastern markets as black teas, but there is general confusion due to improper use of the terms "oxidation" and "fermentation". Typically black tea is termed "fully fermented", which is incorrect as the process used to create black tea is oxidation and does not involve microbial activity. Black teas are fully oxidized, green teas are unoxidized, and Oolong teas are partially oxidized to varying degrees.

All pu'er teas undergo some oxidation during sun drying and then become either:

- Fully fermented with microbes during a processing phase which is largely anaerobic, i.e. without the presence of oxygen. This phase is similar to composting and results in Shu (ripened) pu'er

- Partly fermented by microbial action, and partly oxidized during the natural aging process resulting in Sheng (raw) pu'er. The aging process depends on how the sheng pu'er is stored, which determines the degree of fermentation and oxidization achieved.

According to the production process, four main types of pu'er are commonly available on the market:

- Maocha, green pu'er leaves sold in loose form as the raw material for making pressed pu'er. Badly processed maocha will produce an inferior pu'er.

- Green/raw pu'er, pressed maocha that has not undergone additional processing; high quality green pu'er is highly sought by collectors.

- Ripened/cooked pu'er, maocha that has undergone an accelerated fermentation process lasting 45 to 60 days on average. Badly fermented maocha will create a muddy tea with fishy and sour flavors indicative of inferior aged pu'er.

- Aged raw pu'er, a tea that has undergone a slow secondary oxidation and microbial fermentation. Although all types of pu'er can be aged, the pressed raw pu'er is typically the most highly regarded, since aged maocha and ripened pu'er both lack a clean and assertive taste.

Regions

Yunnan

Pu'er is produced in almost every county and prefecture in the province. Proper pu'er is sometimes considered to be limited to that produced in Pu'er City.

Six Great Tea Mountains

The best known pu'er areas are the Six Great Tea Mountains (Chinese: 六大茶山; pinyin: liù dà chá shān[26]), a group of mountains in Xishuangbanna, Yunnan, renowned for their climates and environments, which not only provide excellent growing conditions for pu'er, but also produce unique taste profiles (akin to terroir in wine) in the produced pu'er tea. Over the course of history, the designated mountains for the tea mountains have either been changed[27] or listed differently.[28][29][30]

In the Qing dynasty government records for Pu'er (普洱府志), the oldest historically designated mountains were said to be named after six commemorative items left in the mountains by Zhuge Liang,[29] and using the Chinese characters of the native languages (Hani and Tai) of the region.[31] These mountains are all located northeast of the Lancang River (Mekong) in relatively close proximity to one another. The mountains' names, in the Standard Chinese character pronunciation are:

Southwest of the river there are also nine lesser known tea mountains, which are isolated by the river.[30] They are:

- Mengsong (勐宋):

- Pasha (帕沙):

- Jingmai (景迈):

- Nánnuò (南糯): a varietal of tea grows here called zĭjuān (紫娟, literally "purple lady") whose buds and bud leaves have a purple hue.

- Bada (巴达):

- Hekai (贺开):

- Bulangshan (布朗山):

- Mannuo (曼糯):

- Xiao mengsong (小勐宋):

For various reasons, around the end of the Qing dynasty and at the beginning of the ROC period (the early twentieth century), tea production in these mountains dropped drastically, either due to large forest fires, overharvesting, prohibitive imperial taxes, or general neglect.[27][31] To revitalize tea production in the area, the Chinese government in 1962 selected a new group of six great tea mountains that were named based on the more important tea-producing mountains at the time, including Youle mountain from the original six.[27]

Other areas of Yunnan

Many other areas of Yunnan also produce pu'er tea. Yunnan prefectures that are major producers of pu'er include Lincang, Dehong, Simao, Xishuangbanna, and Wenshan. Other notable tea mountains famous in Yunnan include among others:

- Bāngwǎi (邦崴山)

- Bānzhāng (班章): this is not a mountain but a Hani village in the Bulang Mountains, noted for producing powerful and complex teas that are bitter with a sweet aftertaste

- Yìwǔ (易武山)

- Bada (巴達山)

- Wuliang

- Ailuo

- Jinggu

- Baoshan

- Yushou

Region is but one factor in assessing a pu'er tea, and pu'er from any region of Yunnan is as prized as any from the Six Great Tea Mountains if it meets other criteria, such as being wild growth, hand-processed tea.

Other provinces

While Yunnan produces the majority of pu'er, other regions of China, including Hunan and Guangdong, have also produced the tea. The Guangyun Gong cake, for example, although the early productions were composed of pure Yunnan máochá,[32] after the 60's the cakes featured a blend of Yunnan and Guangdong máochá, and the most recent production of these cakes contains mostly from the latter.[33]

In late 2008, the Chinese government approved a standard declaring pu'er tea as a "product with geographical indications", which would restrict the naming of tea as pu'er to tea produced within specific regions of the Yunnan province. The standard has been disputed, particularly by producers from Guangdong.[34] Fermented tea in the pu'er style made outside of Yunnan is often branded as "dark tea" in light of this standard.

Other regions

In addition to China, border regions touching Yunnan in Vietnam, Laos, and Burma are also known to produce pu'er tea, though little of this makes its way to the Chinese or international markets.

Cultivation

Perhaps equally or even more important than region or even grade in classifying pu'er is the method of cultivation. Pu'er tea can come from three different cultivation methods:

- Plantation bushes (guànmù, 灌木; taídì, 台地): Cultivated tea bushes, from the seeds or cuttings of wild tea trees and planted in relatively low altitudes and flatter terrain. The tea produced from these plants are considered inferior due to the use of pesticides and chemical fertilizer in cultivation, and the lack of pleasant flavors, and the presence of harsh bitterness and astringency from the tea.

- "Wild arbor" trees (yěfàng, 野放): Most producers claim that their pu'er is from wild trees, but most use leaves from older plantations that were cultivated in previous generations that have gone feral due to the lack of care. These trees produce teas of better flavor due to the higher levels of secondary metabolites produced in the tea tree. As well, the trees are typically cared for using organic practices, which includes the scheduled pruning of the trees in a manner similar to pollarding. Despite the good quality of their produced teas, "wild arbor" trees are not as prized as the truly wild trees.

- Wild trees (gŭshù, 古树; literally "old tree"): Teas from old wild trees, grown without human intervention, are the highest valued pu'er teas. Such teas are valued for having deeper and more complex flavors, often with camphor or "mint" notes, said to be imparted by the many camphor trees that grow in the same environment as the wild tea trees. Young raw pu'er teas produced from the leaf tips of these trees also lack overwhelming astringency and bitterness often attributed to young pu'er. Pu'er made from the distinct but closely related so-called wild species Camellia taliensis can command a much higher price than pu'er made from the more common Camellia sinensis.[35]

Determining whether or not a tea is wild is a challenging task, made more difficult through the inconsistent and unclear terminology and labeling in Chinese. Terms like yěshēng (野生; literally "wild" or "uncultivated"), qiáomù (乔木; literally "tall tree"), yěshēng qiáomù (野生乔木; literally "uncultivated trees"), and gǔshù are found on the labels of cakes of both wild and "wild arbor" variety, and on blended cakes, which contain leaves from tea plants of various cultivations. These inconsistent and often misleading labels can easily confuse uninitiated tea buyers regardless of their grasp of the Chinese language. As well, the lack of specific information about tea leaf sources in the printed wrappers and identifiers that come with the pu'er cake makes identification of the tea a difficult task. Pu'er journals and similar annual guides such as The Profound World of Chi Tse, Pu-erh Yearbook, and Pu-erh Teapot Magazine contain credible sources for leaf information. Tea factories are generally honest about their leaf sources, but someone without access to tea factory or other information is often at the mercy of the middlemen or an unscrupulous vendor. Many pu'er aficionados seek out and maintain relationships with vendors who they feel they can trust to help mitigate the issue of finding the "truth" of the leaves.

Sadly, even in the best of circumstances, when a journal, factory information, and trustworthy vendor all align to assure a tea's genuinely wild leaf, fakes fill the market and make the issue even more complicated. Because collectors often doubt the reliability of written information, some believe certain physical aspects of the leaf can point to its cultivation. For example, drinkers cite the evidence of a truly wild old tree in a menthol effect ("camphor" in tea specialist terminology) supposedly caused by the Camphor laurel trees that grow amongst wild tea trees in Yunnan's tea forests. As well, the presence of thick veins and sawtooth-edged on the leaves along with camphor flavor elements and taken as signifiers of wild tea.

Grade

Pu'er can be sorted into ten or more grades. Generally, grades are determined by leaf size and quality, with higher numbered grades meaning older/larger, broken, or less tender leaves. Grading is rarely consistent between factories, and first grade tea leaves may not necessarily produce first grade cakes. Different grades have different flavors; many bricks blend several grades chosen to balance flavors and strength.

Season

Harvest season also plays an important role in the flavor of pu'er. Spring tea is the most highly valued, followed by fall tea, and finally summer tea. Only rarely is pu'er produced in winter months, and often this is what is called "early spring" tea, as harvest and production follows the weather pattern rather than strict monthly guidelines.

Tea factories

Factories are generally responsible for the production of pu'er teas. While some individuals oversee small-scale production of high-quality tea, such as the Xizihao and Yanqinghao brands, the majority of tea on the market is compressed by factories or tea groups. Until recently factories were all state-owned and under the supervision of the China National Native Produce & Animal Byproducts Import & Export Corporation (CNNP), Yunnan Tea Branch. Kunming Tea Factory, Menghai Tea Factory, Pu'er Tea Factory and Xiaguan Tea Factory are the most notable of these state-owned factories. While CNNP still operates today, few factories are state-owned, and CNNP contracts out much production to privately owned factories.

Different tea factories have earned good reputations. Menghai Tea Factory and Xiaguan Tea Factory, which date from the 1940s, have enjoyed good reputations, but in the twentyfirst century face competition from many of the newly emerging private factories. For example, Haiwan Tea Factory, founded by former Menghai Factory owner Zhou Bing Liang in 1999,[36] has a good reputation, as do Changtai Tea Group, Mengku Tea Company, and other new tea makers formed in the 1990s. However, due to production inconsistencies and variations in manufacturing techniques, the reputation of a tea company or factory can vary depending on the year or the specific cakes produced during a year.

The producing factory is often the first or second item listed when referencing a pu'er cake, the other being the year of production.

Recipes

Tea factories, particularly formerly government-owned factories, produce many cakes using recipes for tea blends, indicated by a four-digit recipe number. The first two digits of recipe numbers represent the year the recipe was first produced, the third digit represents the grade of leaves used in the recipe, and the last digit represents the factory. The number 7542, for example, would denote a recipe from 1975 using fourth-grade tea leaf made by Menghai Tea Factory (represented by 2).

- Factory numbers (fourth digit in recipe):

- Kunming Tea Factory

- Menghai Tea Factory aka Dayi

- Xiaguan

- Lan Cang Tea Factory or Feng Qing Tea Factory

- Pu-erh Tea Factory (now Pu-erh Tea group Co. Ltd )

- Six Famous Tea Mountain Factory

- unknown / not specified

- Haiwan Tea Factory and Long Sheng Tea Factory

Tea of all shapes can be made by numbered recipe. Not all recipes are numbered, and not all cakes are made by recipe. The term "recipe," it should be added, does not always indicate consistency, as the quality of some recipes change from year-to-year, as do the contents of the cake. Perhaps only the factories producing the recipes really know what makes them consistent enough to label by these numbers.

Occasionally, a three digit code is attached to the recipe number by hyphenation. The first digit of this code represents the year the cake was produced, and the other two numbers indicate the production number within that year. For instance, the seven digit sequence 8653-602, would indicate the second production in 2006 of factory recipe 8653. Some productions of cakes are valued over others because production numbers can indicate if a tea was produced earlier or later in a season/year. This information allows one to be able to single out tea cakes produced using a better batch of máochá.

Tea packaging

Pu'er tea is specially packaged for trade, identification, and storage. These attributes are used by tea drinkers and collectors to determine the authenticity of the pu'er tea.

Individual cakes

Pu'er tea cakes, or bĭngchá, are almost always sold with a:[37]

- Wrapper: Made usually from thin cotton cloth or cotton paper and shows the tea company/factory, the year of production, the region/mountain of harvest, the plant type, and the recipe number. The wrapper can also contain decals, logos and artwork. Occasionally, more than one wrapper will be used to wrap a pu'er cake.

- Nèi fēi (内飞 or 內飛): A small ticket originally stuck on the tea cake but now usually embedded into the cake during pressing. It is usually used as proof, or a possible sign, to the authenticity of the tea. Some higher end pu'er cakes have more than one nèi fēi embedded in the cake. The ticket usually indicates the tea factory and brand.

- Nèi piào (内票): A larger description ticket or flyer packaged loose under the wrapper. Both aid in assuring the identity of the cake. It usually indicates factory and brand. As well, many nèi piào contain a summary of the tea factories' history and any additional laudatory statements concerning the tea, from its taste and rarity, to its ability to cure diseases and effect weight loss.

- Bĭng: The tea cake itself. Tea cakes or other compressed pu'er can be made up of two or more grades of tea, typically with higher grade leaves on the outside of the cake and lower grades or broken leaves in the center. This is done to improve the appearance of the tea cake and improve its sale. Predicting the grade of tea used on the inside takes some effort and experience in selection. However, the area in and around the dimple of the tea cake can sometimes reveal the quality of the inner leaves.

.jpg)

Recently, nèi fēi have become more important in identifying and preventing counterfeits. Menghai Tea Factory in particular has begun microprinting and embossing their tickets in an effort to curb the growth of counterfeit teas found in the marketplace in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Some nèi fēi also include vintage year and are production-specific to help identify the cake and prevent counterfeiting through a surfeit of different brand labels.

Counterfeit pu'er is common. The practices include claiming the tea is older than it actually is, misidentifying the origin of the leaf as Yunnan instead of a non-Yunnan region, labeling terrace tea as forest tea, and selling green tea instead of raw pu'er. The interpretation of the packing of pu'er is usually dependent on the consumer's knowledge and negotiation between the consumer and trader.

Wholesale

When bought in large quantities, pu'er tea is generally sold in stacks, referred to as a tǒng (筒), which are wrapped in bamboo shoot husks, bamboo stem husks, or coarse paper. Some tongs of vintage pu'er will contain a tǒng piào (筒票), or tong ticket, but it is less common to find them in productions past the year 2000.[12] The number of bǐngchá in a tǒng varies depending on the weight of individual bǐngchá. For instance one tǒng can contain:

- Seven 357–500g 'bǐngchá',

- Five 250g mini-'bǐngchá'

- Ten 100g mini-'bǐngchá'

Twelve tǒng are referred to as being one jiàn (件), although some producers/factories vary how many tǒng equal one jiàn. A jiàn of tea, which is bound together in a loose bamboo basket, will usually have a large batch ticket (大票; pinyin: dàpiào) affixed to its side that will indicate information such as the batch number of the tea in a season, the production quantities, tea type, and the factory where it was produced.[12]

Aging and storage

Pu'er teas of all varieties, shapes, and cultivation can be aged to improve their flavor, but the tea's physical properties will affect the speed of aging as well as its quality. These properties include:

- Leaf quality: The most important factor, arguably, is leaf quality. Maocha that has been improperly processed will not age to the level of finesse as properly processed maocha. The grade and cultivation of the leaf also greatly affect its quality, and thus its aging.

- Compression: The tighter a tea is compressed, the slower it will age. In this respect, looser hand- and stone-pressed pu'er teas will age more quickly than denser hydraulic-pressed pu'er.

- Shape and size : The more surface area, the faster the tea will age. Bǐngchá and zhuancha thus age more quickly than golden melon, tuocha, or jincha. Larger bingcha age slower than smaller 'bǐngchá', and so forth.

Just as important as the tea's properties, environmental factors for the tea's storage also affect how quickly and successfully a tea ages. They include:

- Air flow: Regulates the oxygen content surrounding the tea and removes odors from the aging tea. Dank, stagnant air will lead to dank, stale smelling aged tea. Wrapping a tea in plastic will eventually arrest the aging process.

- Odors: Tea stored in the presence of strong odors will acquire them, sometimes for the duration of their "lifetime." Airing out pu'er teas can reduce these odors, though often not completely.

- Humidity : The higher the humidity, the faster the tea will age. Liquid water accumulating on tea may accelerate the aging process but can also cause the growth of mold or make the flavor of the tea less desirable. 60–85% humidity is recommended.[38] It is argued whether tea quality is adversely affected if it is subjected to highly fluctuating humidity levels.

- Sunlight: Tea that is exposed to sunlight dries out prematurely, and often becomes bitter.

- Temperature: Teas should not be subjected to high heat since undesirable flavors will develop. However at low temperatures, the aging of pu'er tea will slow down drastically. It is argued whether tea quality is adversely affected if it is subjected to highly fluctuating temperature.

When preserved as part of a tong, the material of the tong wrapper, whether it is made of bamboo shoot husks, bamboo leaves, or thick paper, can also affect the quality of the aging process. The packaging methods change the environmental factors and may even contribute to the taste of the tea itself.

Further to what has been mentioned it should be stressed that a good well-aged pu'er tea is not evaluated by its age alone. Like all things in life, there will come a time when a pu'er teacake reaches its peak before stumbling into a decline. Due to the many recipes and different processing methods used in the production of different batches of pu'er, the optimal age for each tea will vary. Some may take 10 years while others 20 or 30+ years. It is important to check the status of ageing for your teacakes to know when they have peaked so that proper care can be given to halt the ageing process.

Raw pu'er

Over time, raw pu'er acquires an earthy flavor due to slow oxidation and other, possibly microbial processes. However, this oxidation is not analogous to the oxidation that results in green, oolong, or black tea, because the process is not catalyzed by the plant's own enzymes but rather by fungal, bacterial, or autooxidation influences. Pu'er flavors can change dramatically over the course of the aging process, resulting in a brew tasting strongly earthy but clean and smooth, reminiscent of the smell of rich garden soil or an autumn leaf pile, sometimes with roasted or sweet undertones. Because of its ability to age without losing "quality", well aged good pu'er gains value over time in the same way that aged roasted oolong does.[39]

Raw pu'er can undergo "wet storage" (shīcāng, 湿仓) and "dry storage" (gāncāng 干仓), with teas that have undergone the latter ageing more slowly, but thought to show more complexity. Dry storage involves keeping the tea in "comfortable" temperature and humidity, thus allowing the tea to age slowly. Wet or "humid" storage refers to the storage of pu'er tea in humid environments, such as those found naturally in Hong Kong, Guangzhou and, to a lesser extent, Taiwan.

The practice of "Pen Shui" 喷水 involves spraying the tea with water and allowing it dry off in a humid environment. This process speeds up oxidation and microbial conversion, which only loosely mimics the quality of natural dry storage aged pu'er. "Pen Shui" 喷水 pu'er not only does not acquire the nuances of slow aging, it can also be hazardous to drink because of mold, yeast, and bacteria cultures.

Pu'er properly stored in different environments can develop different tastes at different rates due to environmental differences in ambient humidity, temperature, and odors.[12] For instance, similar batches of pu'er stored in the different environments of Taiwan and Hong Kong are known to age very differently. Because the process of aging pu'er is lengthy, and teas may change owners several times, a batch of pu'er may undergo different aging conditions, even swapping wet and dry storage conditions, which can drastically alter its flavor. Raw pu'er can be ruined by storage at very high temperatures, or exposure to direct contact with sunlight, heavy air flow, liquid water, or unpleasant smells.

Although low to moderate air flow is important for producing a good-quality aged raw pu'er, it is generally agreed by most collectors and connoisseurs that raw pu'er tea cakes older than 30 years should not be further exposed to "open" air since it would result in the loss of flavors or degradation in mouthfeel. The tea should instead be preserved by wrapping or hermetically sealing it in plastic wrapping or ideally glass.

Ripe pu'er

Since the ripening process was developed to imitate aged raw pu'er, many arguments surround the idea of whether aging ripened pu'er is desirable. Mostly, the issue rests on whether aging ripened pu'er will, better or worse, alter the flavor of the tea.

It is often recommended to age ripened pu'er to air out the unpleasant musty flavors and odors formed due to maocha fermentation. However, some collectors argue that keeping ripened pu'er longer than 10 to 15 years makes little sense, stating that the tea will not develop further and possibly lose its desirable flavors. Others note that their experience has taught them that ripened pu'er indeed does take on nuances through aging,[37] and point to side-by-side taste comparisons of ripened pu'er of different ages. Aging the tea increases its value, but may be unprofitable.

Vintaging

The common misconception is that all types of pu'er tea will improve in taste—and therefore gain in value—as they get older. There are many requisite variables for a pu'er tea to age beautifully. Further, the ripe (shu) pu'er will not evolve as dramatically as the raw (sheng) type will over time due to secondary oxidation and fermentation.

As with aging wine, only finely made and properly stored teas will improve and increase in value. Similarly, only a small percentage of teas will improve over a long period of time.

From 2008 Pu'er prices dropped dramatically. Investment-grade Pu'er did not drop as much as the more common varieties. Many producers made large losses, and some decided to leave the industry altogether.[40]

Preparation

Preparation of pu'erh involves first separating a well-sized portion of the compressed tea for brewing. This can be done by flaking off pieces of the cake or by steaming the entire cake until it is soft from heat and hydration.[37] A pu'erh knife, which is similar to an oyster knife or a rigid letter opener, is used to pry large horizontal flakes of tea off the cake to minimize leaf breakage. Smaller cakes such as tuocha or mushroom pu'erh are often steamed until they can be rubbed apart and then dried. In both cases, a vertical sampling of the cake should be obtained since the quality of the leaves in a cake usually varies between the surface and the center.

Pu'erh is generally expected to be served Gongfu style, generally in Yixing teaware or in a type of Chinese teacup called a gaiwan. Optimum temperatures are generally regarded to be around 95 °C for lower quality pu'erhs and 85–89 °C for good ripened and aged raw pu'erh. The tea is steeped for 12 to 30 seconds in the first few infusions, increasing to 2 to 10 minutes in the last infusions. The prolonged steeping sometimes used in the west can produce dark, bitter, and unpleasant brews. Quality aged pu'erh can yield many more infusions, with different flavor nuances when brewed in the traditional Gong-Fu method.

Because of the prolonged fermentation in ripened pu'erh and slow oxidization of aged raw pu'erh, these teas often lack the bitter, astringent properties of other teas, and can be brewed much stronger and repeatedly, with some claiming 20 or more infusions of tea from one pot of leaves. On the other hand, young raw pu'erh is known and expected to be strong and aromatic, yet very bitter and somewhat astringent when brewed, since these characteristics are believed to produce better aged raw pu'erh.

Judging quality

Quality of the tea can be determined through inspecting the dried leaves, the tea liquor, or the spent tea leaves. The "true" quality of a specific batch of pu'erh can ultimately only be revealed when the tea is brewed and tasted. Although not concrete and sometimes dependent on preference, there are several general indicators of quality:

- Dried tea: There should be a lack of twigs, extraneous matter and white or dark mold spots on the surface of the compressed pu'erh. The leaves should ideally be whole, visually distinct, and not appear muddy. The leaves may be dry and fragile, but not powdery. Good tea should be quite fragrant, even when dry. Good pressed pu'er cakes often have a matte sheen on the surface, though this is not necessarily a sole indicator of quality.

- Liquor: The tea liquor of both raw and ripe pu'erh should never appear cloudy. Well-aged raw pu'erh and well-crafted ripe pu'erh tea may produce a dark reddish liquor, reminiscent of a dried jujube, but in either case the liquor should not be opaque, "muddy," or black in color. The flavors of pu'erh liquors should persist and be revealed throughout separate or subsequent infusions, and never abruptly disappear, since this could be the sign of added flavorants.

- Young raw pu'erh: The ideal liquors should be aromatic with a light but distinct odors of camphor, rich herbal notes like Chinese medicine, fragrance floral notes, hints of dried fruit aromas such as preserved plums, and should exhibit only some grassy notes to the likes of fresh sencha. Young raw pu'er may sometimes be quite bitter and astringent, but should also exhibit a pleasant mouthfeel and "sweet" aftertaste, referred to as gān (甘) and húigān (回甘).

- Aged raw pu'erh: Aged pu'er should never smell moldy, musty, or strongly fungal, though some pu'erh drinkers consider these smells to be unoffensive or even enjoyable. The smell of aged pu'erh may vary, with an "aged" but not "stuffy" odor. The taste of aged raw pu'erh or ripe pu'erh should be smooth, with slight hints of bitterness, and lack a biting astringency or any off-sour tastes. The element of taste is an important indicator of aged pu'erh quality, the texture should be rich and thick and should have very distinct gān (甘) and húigān (回甘) on the tongue and cheeks, which together induces salivation and leaves a "feeling" in the back of the throat.

- Spent tea: Whole leaves and leaf bud systems should be easily seen and picked out of the wet spent tea, with a limited amount of broken fragments. Twigs and the fruits of the tea plant should not be found in the spent tea leaves; however, animal (and human) hair, strings, rice grains and chaff may occasionally be included in the tea. The leaves should not crumble when rubbed, and with ripened pu'erh, it should not resemble compost. Aged raw pu'erh should have leaves that unfurl when brewed while leaves of most ripened pu'erh will generally remain closed.

Practices

In Cantonese culture, pu'erh is known as po-lay (or bo-lay) tea (Cantonese Yale: bou2 nei2). Among the Cantonese long settled in California, it is called bo-nay or po-nay tea. It is often drunk during dim sum meals, as it is believed to help with digestion. It is not uncommon to add dried osmanthus flowers, pomelo rinds, or chrysanthemum flowers into brewing pu'er tea in order to add a light, fresh fragrance to the tea liquor. Pu'er with chrysanthemum is the most common pairing, and referred as guk pou or guk bou (菊普; Cantonese Yale: guk1 pou2; pinyin: jú pǔ).

Sometimes wolfberries are brewed with the tea, plumping in the process.

Health

Pu'er tea is widely sold, by itself or in blends, with unsubstantiated claims that it promotes loss of body weight in humans. Unlike pu'er, some Bianxiao brick tea has been found to contain very high levels of fluorine. This is because Bianxiao tea is generally made from lesser-quality older tea leaves and stems, which accumulate fluorine.[41] Its consumption has led to fluorosis (a form of fluoride poisoning that affects the bones and teeth) in areas of high brick tea consumption, such as Tibet.[42][43]

Popular culture

In the Japanese manga Dragon Ball, the name of the character Pu'ar is a pun on pu'er tea.

See also

Notes

- Among many of the minority groups of China's southwest, the Chinese character 鉧 is used to indicate cauldrons or pots.[44] The original transliteration of this character in The Great Tea Mountains of Southern Yunnan, however, is "boa".[27]

References

- Yoder, Austin (2013-05-13). "Pu'er Vs. Pu-erh: What's the Deal with the Different Spellings?". Tearroir. Archived from the original on 2016-05-07.

- Chen ZM (1991), p. 438, chpt. "Manufacturing pu'er [普洱茶的制造]"

- Zhang (2013), p. 206, appx. 1: "Puer Tea Categories and Production Process"

- TeaHub.com (2013). "Talks about Black (Shu/Ripe) Pu-erh". Articles3K.com. Archived from the original on 2016-05-30. Retrieved 2014-05-03.

- Zhang (2013), p. 45, chpt. 1

- Vu, Huyen Trang; Song, Fu V.; Tian, Kun V.; Su, Haibin; Chass, Gregory A. (2019-11-15). "Systematic characterisation of the structure and radical scavenging potency of Pu'Er tea (普洱) polyphenol theaflavin". Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry. 17: 9942–9950. doi:10.1039/C9OB02007A. ISSN 1477-0539.

- Chen ZM (1991), pp. 246–248, chpt. "Types of black tea [黑茶的種類]"

- "Tea, City Share Pu'er Name", CRI English, Beijing: China Radio International, 8 April 2007.

- Zhāng Tíngyù [張廷玉] (1739). 食貨誌 [Food & Money]. Míng Shǐ 明史 [History of Ming]. 80/4.

- Léi Píngyáng [雷平陽] (2005). Pǔ'ěr chá jì 普洱茶記 [Tea In Mind]. Yunnan Art Press [雲南民族出版社]. ISBN 9787806953174.

- Cf. Sū Fānghuá [苏芳华] (2005). "Pu'er chá bu shu heichá de pingxi" 普洱茶不属黑茶的评析 [Discussion and analysis on whether Pu'er is a type of fermented (black) tea]. Zhōngguó cháyè 中国茶叶 [Chinese Tea] (1): 38–39. For a rebuttal, see Xià Chéngpéng [夏成鹏] (2005). "Pu'er chá jishu heichá" 普洱茶即属黑茶 [Pu'er tea is a type of fermented (black) tea]. Zhōngguó cháyè 中国茶叶 [Chinese Tea] (4): 45–46.

- Chan Kam Pong (November 2006). First Step to Chinese Puerh Tea. Taipei: WuShing Books [五行圖書出版有限公司].

- Chén Kě-Kě [陈可可]; Zhū Hóng-Tāo [朱宏涛]; Wáng Dōng [王东]; Zhāng Yǐng-Jūn [张颖君]; Yáng Chóng-Rén [杨崇仁] (2006). 普洱熟茶后发酵加工过程中曲霉菌的分离和鉴定 [Isolation and identification of Aspergillus species from the post fermentative process of Pu-Er ripe tea]. Acta Botanica Yunnanica [云南植物研究]. 28 (2): 123–126. Retrieved 2018-03-23.

- Tian, Jianqing; Zhu, Zixiang; Wu, Bing; Wang, Lin; Liu, Xingzhong (2013-08-19). "Bacterial and fungal communities in Pu'er tea samples of different ages". Journal of Food Science. 78 (8): M1249–1256. doi:10.1111/1750-3841.12218. PMID 23957415.

- Zhang, Liang; Li, Ning; Ma, Zhizhong; Tu, Pengfei (2011-08-24). "Comparison of the chemical constituents of aged pu-erh tea, ripened pu-erh tea, and other teas using HPLC-DAD-ESI-MSn". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 59 (16): 8754–8760. doi:10.1021/jf2015733. PMID 21793506.

- Yè Wěi [叶伟]. 纯正的云南普洱茶/真正的干仓普洱茶 [Authentic Yunnan Pu'er– Making Dry Pu'er Tea]. ynttc.com. Archived from the original on 2009-03-01.

- Mo, Haizhen; Zhu, Yang; Chen, Zongmao (2008). "Microbial fermented tea – a potential source of natural food preservatives". Trends in Food Science and Technology. 19 (3): 124–130. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2007.10.001.

- Jeng, Kee-Ching; Chen, Chin-Shuh; Fang, Yu-Pun; Hou, Rolis Chien-Wei; Chen, Yuh-Shuen (2007). "Effect of microbial fermentation on content of statin, GABA, and polyphenols in Pu-Erh tea". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 55 (21): 8787–8792. doi:10.1021/jf071629p. PMID 17880152.

- Gong, Jia-shun; Zhou, Hong-jie; Zhang, Xin-fu; Song, Shan; An, Wen-jie (2005). "Changes of Chemical Components in Pu'er Tea Produced by Solid State Fermentation of Sundried Green Tea". Journal of Tea Science. 25 (4): 300–306. Retrieved 2018-03-23.

- Abe, Michiharu; Takaoka, Naohiro; Idemoto, Yoshito; Takagi, Chihiro; Imai, Takuji; Nakasaki, Kiyohiko (2008-05-31). "Characteristic fungi observed in the fermentation process for Puer tea". International Journal of Food Microbiology. 124 (2): 199–203. doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.03.008. PMID 18455823.

- Zhou, Hong-jie; Li, Jia-hua; Zhao, Long-fei; Han, Jun; Yang, Xing-ji; Yang, Wei; Wu, Xin-zhuang (2004). "Study on Main Microbes of Quality Formation of Yunnan Puer Tea during Pile-fermentation Process". Journal of Tea Science. 24 (3): 212–218. Retrieved 2018-03-23.

- Zhao, ZJ; Tong, HR; Zhou, L; Wang, EX; Liu, QJ (2010). "Fungal Colonization of Pu-Erh Tea in Yunnan". Journal of Food Safety. 30 (4): 769–784. doi:10.1111/j.1745-4565.2010.00240.x.

- Hong, Seung-Beom; Lee, Mina; Kim, Dae-Ho; Varga, Janos; Frisvad, Jens C.; Perrone, Giancarlo; Gomi, Katsuya; Yamada, Osamu; Machida, Masayuki; Houbraken, Jos; Samson, Robert A. (2013-05-28). "Aspergillus luchuensis, an industrially important black Aspergillus in East Asia". PLoS ONE. 8 (5): e63769. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...863769H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0063769. PMC 3665839. PMID 23723998.

- Mogensen, Jesper M.; Varga, J.; Thrane, Ulf; Frisvad, Jens C. (2009-04-21). "Aspergillus acidus from Puerh tea and black tea does not produce ochratoxin A and fumonisin B-2". International Journal of Food Microbiology. 132 (2–3): 141–144. doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.04.011. PMID 19439385.

- Cloud Tea Network [云茶网] (2006). 云南名茶 [Yunnan Tea]. Yunnan Information Portal [云南信息港]. Archived from the original on 2007-11-14.

- Forbes, Andrew; Henley, David (2011). "Six Great Tea Mountains". China's Ancient Tea Horse Road. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ISBN 9781300464860.

- The Tao Of Tea (1998-09-26). "Tea Map – Jingmai, Yunnan". Retrieved 2018-03-23.

- Jiǎng Quán [蒋铨] (2005-08-29). 古"六大茶山"访问记 [Historic travel to the "Six Dasan Mountains"]. Yunnan Pu'er Tea Network [云南普洱茶网]. Kunming Province Tea Cultural Communication Co., Ltd. [昆明新境茶文化传播有限公司]. Archived from the original on 2009-02-27. Retrieved 2006-12-16.

- Fú Yóu [蜉蝣] (2005-07-26). 六大茶山考 [The Six Dasan Mountains Test]. Archived from the original on 2007-07-19 – via TOM.com 文化 [Culture].CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)

- 云南普洱茶分布 [Pu'er tea distribution in Yunnan]. 7yunnan.cn. 2006. Archived from the original on 2006-12-02.

- 古"六大茶山"概况 [History of the "Six Dasan Mountains"]. 西双版纳明成科技有限公司互联网部 [Ming Cheng Technology, Xishuangbanna – Internet Dept.]. Archived from the original on 2007-07-03.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)

- David Collen, "1960's Guang Yun Gong". The Essence of Tea. 2014. Retrieved 2018-03-23.

- Guang Lee (2007-05-01). "60's Guang Yun Gong in Original Tong". Hou De Tea Blog. Archived from the original on 2013-01-30 – via May 2007 Archive.

- Shen Jingting (2009-06-15). "Tempest over tea: What is the true Puer?". China Daily. Retrieved 2018-03-23.

- Liu, Yang; Yang, Shi-xiong; Ji, Peng-zhang; Gao, Li-zhi (2012-06-21). "Phylogeography of Camellia taliensis (Theaceae) inferred from chloroplast and nuclear DNA: insights into evolutionary history and conservation". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 12 (92): 92. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-12-92. PMC 3495649. PMID 22716114.

- Jing Tea Shop (2005). "2005 Haiwan Lao Tong Zhi Label". Archived from the original on 2006-10-18.

- "Pu-erh Information". Hou De Asian Art & Fine Tea. 2012. Archived from the original on 2011-07-12. Retrieved 2018-03-23.

- Jing Tea Shop (2007). "How to store your pu-erh tea". Archived from the original on 2007-05-18. Jing Tea Shop(2005)

- Guang Chung Lee (2006). "The Varieties of Formosa Oolong". The Art of Tea. No. 1. Taipei: WuShing Books [五行圖書出版有限公司]. Archived from the original on 2007-10-07.

- Jacobs, Andrew (2009-01-16). "A County In China Sees Its Fortunes In Tea Leaves Until a Bubble Bursts". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- Cao, J.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, J.W. (December 1998). "Safety evaluation and fluorine concentration of pu'er brick tea and bianxiao brick tea". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 36 (12): 1061–1063. doi:10.1016/S0278-6915(98)00087-8. PMID 9862647.

- Cao, Jin; Bai, Xuexin; Zhao, Yan; Liu, Jianwei; Zhou, Dingyou; Fang, Shiliang; Jia, Ma; Wu, Jinsheng (December 1996). "The Relationship of Fluorosis and Brick Tea Drinking in Chinese Tibetans". Environmental Health Perspectives. 104 (12): 1340–1343. doi:10.2307/3432972. JSTOR 3432972. PMC 1469557. PMID 9118877.

- Cao, J; Zhao, Y; Liu, J (September 1997). "Brick tea consumption as the cause of dental fluorosis among children from Mongol, Kazak and Yugu populations in China". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 35 (8): 827–833. doi:10.1016/s0278-6915(97)00049-5. PMID 9350228.

- 户崎哲彦, 2001,"钴鉧"不是熨斗而是釜锅之属--柳宗元的文学成就与西南少数民族的语言文化, 柳州师专学报 (On "Gumu" Not Being an Iron but a Category of Cauldron or Pot)

- Chén Zōngmào [陳宗懋] (1991). Zhōngguó chájīng 中國茶經 [Chinese Tea] (in Chinese). Shanghai Culture Press [上海文化出版社]. ISBN 978-7-80511-499-6.

- Zhang, Jinghong (2013). Puer Tea: Ancient Caravans and Urban Chic. Seattle & London: University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-99323-2.