Nicolas Poussin

Nicolas Poussin (UK: /ˈpuːsæ̃/, US: /puːˈsæ̃/,[1][2] French: [nikɔlɑ pusɛ̃]; June 1594 – 19 November 1665) was the leading painter of the classical French Baroque style, although he spent most of his working life in Rome. Most of his works were on religious and mythological subjects painted for a small group of Italian and French collectors. He returned to Paris for a brief period to serve as First Painter to the King under Louis XIII and Cardinal Richelieu, but soon returned to Rome and resumed his more traditional themes. In his later years he gave growing prominence to the landscapes in his pictures. His work is characterized by clarity, logic, and order, and favors line over color. Until the 20th century he remained a major inspiration for such classically-oriented artists as Jacques-Louis David, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and Paul Cézanne.

Nicolas Poussin | |

|---|---|

Self portrait by Nicolas Poussin, 1650 | |

| Born | June 1594 |

| Died | 19 November 1665 (aged 71) |

| Nationality | French |

| Known for | Painting |

Notable work | Et in Arcadia ego, 1637–38 |

| Movement | Classicism Baroque |

Details of Poussin's artistic training are somewhat obscure. Around 1612 he traveled to Paris, where he studied under minor masters and completed his earliest surviving works. His enthusiasm for the Italian works he saw in the royal collections in Paris motivated him to travel to Rome in 1624, where he studied the works of Renaissance and Baroque painters—especially Raphael, who had a powerful influence on his style. He befriended a number of artists who shared his classicizing tendencies, and met important patrons, such as Cardinal Francesco Barberini and the antiquarian Cassiano dal Pozzo. The commissions Poussin received for modestly scaled paintings of religious, mythological, and historical subjects allowed him to develop his individual style in works such as The Death of Germanicus, The Massacre of the Innocents, and the first of his two series of the Seven Sacraments.

He was persuaded to return to France in 1640 to be First Painter to the King but, dissatisfied with the overwhelming workload and the court intrigues, returned permanently to Rome after a little more than a year. Among the important works from his later years are Orion Blinded Searching for the Sun, Landscape with Hercules and Cacus, and The Seasons.

Biography

Early years – Les Andelys and Paris

Nicolas Poussin's early biographer was his friend Giovanni Pietro Bellori,[3] who relates that Poussin was born near Les Andelys in Normandy and that he received an education that included some Latin, which would stand him in good stead. Another early friend and biographer, André Félibien, reported that "He was busy without cease filling his sketchbooks with an infinite number of different figures which only his imagination could produce."[4] His early sketches attracted the notice of Quentin Varin, who passed some time in Andelys, but there is no mention by his biographers that he had a formal training in Varin's studio, though his later works showed the influence of Varin, particularly by their storytelling, accuracy of facial expression, finely painted drapery and rich colors.[5] His parents apparently opposed a painting career for him, and In or around 1612, at the age of eighteen, he ran away to Paris.[4]

He arrived in Paris during the regency of Marie de Medici, when art was flourishing as a result of the royal commissions given by Marie de Medici for the decoration of her palace, and by the rise of wealthy Paris merchants who bought art. There was also a substantial market for paintings in the redecoration of churches outside Paris destroyed during the French Wars of Religion, which had recently ended, and for the numerous convents in Paris and other cities. However, Poussin was not a member of the powerful guild of master painters and sculptors, which had a monopoly on most art commissions and brought lawsuits against outsiders like Poussin who tried to break into the profession.[6]

His early sketches gained him a place in the studios of established painters. He worked for three months in the studio of the Flemish painter Ferdinand Elle, who painted almost exclusively portraits, a genre that was of little interest to Poussin.[7] He moved next to the studio of Georges Lallemand, but Lallemand's inattention to precise drawing and the articulation of his figures apparently displeased Poussin.[7] Moreover, Poussin did not fit well into the studio system, in which several painters worked on the same painting. Thereafter he preferred to work very slowly and alone.[6] Little is known of his life in Paris at this time. Court records show that he ran up considerable debts, which he was unable to pay. He studied anatomy and perspective, but the most important event of his first residence in Paris was his discovery of the royal art collections, thanks to his friendship with Alexandre Courtois, the valet de chambre of Marie de Medicis. There he saw for the first time engravings of the works of Giulio Romano and especially of Raphael, whose work had an enormous influence on his future style.[8]

He first tried to travel to Rome in 1617 or 1618, but made it only as far as Florence, where, as his biographer Bellori reported, "as a result of some sort of accident, he returned to France."[9][10] On his return, he began making paintings for Paris churches and convents. In 1622 made another attempt to go to Rome, but went only as far as Lyon before returning. In the summer of the same year, he received his first important commission: the Order of Jesuits requested a series of six large paintings to honor the canonization of their founder, Saint Francis Xavier. The originality and energy of these paintings (since lost) brought him a series of important commissions.[11]

Giambattista Marino, the court poet to Marie de Medici, employed him to make a series of fifteen drawings, eleven illustrating Ovid's Metamorphoses[12] and four illustrating battle scenes from Roman history. The "Marino drawings", now at Windsor Castle, are among the earliest identifiable works of Poussin.[13] Marino's influence led to a commission for some decoration of Marie de Medici's residence, the Luxembourg Palace, then a commission from the first Archbishop of Paris, Jean-François de Gondi, for a painting of the death of the Virgin (since lost) for the Archbishop's family chapel at the Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris. Marino took him into his household, and, when he returned to Rome in 1623, invited Poussin to join him. Poussin remained in Paris to finish his earlier commissions, then arrived to Rome in the spring of 1624.[14]

First residence in Rome (1624–1640)

Death of Germanicus, 1628, Minneapolis Institute of Arts

Death of Germanicus, 1628, Minneapolis Institute of Arts Venus and Adonis, c. 1628–29, Kimbell Art Museum

Venus and Adonis, c. 1628–29, Kimbell Art Museum.jpg) The Inspiration of the Poet, 1629–30, Louvre

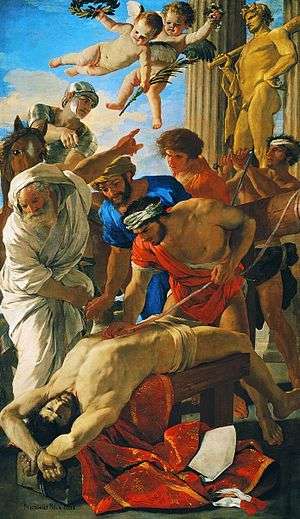

The Inspiration of the Poet, 1629–30, Louvre The Martyrdom of Saint Erasmus 1630, Vatican Museum

The Martyrdom of Saint Erasmus 1630, Vatican Museum

Poussin was thirty when he arrived in Rome in 1624. The new Pope, Urban VIII, elected in 1623, was determined to maintain the position of Rome as the artistic capital of Europe, and artists from around the world gathered there. Poussin could visit the churches and convents to study the works of Raphael and other Renaissance painters, as well as the more recent works of Carracci, Guido Reni and Caravaggio (whose work Poussin detested, saying that Caravaggio was born to destroy painting).[15] He studied the art of painting nudes at the Academy of Domenichino, and frequented the Academy of Saint Luke, which brought together the leading painters in Rome, and whose head in 1624 was another French painter, Simon Vouet, who offered lodging to Poussin.[16]

Poussin became acquainted with other artists in Rome and tended to befriend those with classicizing artistic leanings: the French sculptor François Duquesnoy whom he lodged with in 1626; the French artist Jacques Stella; Claude Lorraine; Domenichino; Andrea Sacchi; and joined an informal academy of artists and patrons opposed to the current Baroque style that formed around Joachim von Sandrart.[17] Rome also offered Poussin a flourishing art market and an introduction to an important number of art patrons. Through Marino, he was introduced to Cardinal Francesco Barberini, the brother of the new Pope, and to Cassiano dal Pozzo, the Cardinal's secretary and a passionate scholar of ancient Rome and Greece, who both later became his important patrons. The new art collectors demanded a different format of paintings; instead of large altarpieces and decoration for palaces, they wanted smaller-size religious paintings for private devotion or picturesque landscapes, mythological and history paintings.[15]

The early years of Poussin in Rome were difficult. His patron Marino departed Rome for Naples in May 1624, shortly after Poussin arrived, and died there in 1625. His other major sponsor, Cardinal Francesco Barberini, was named a papal legate to Spain and also departed soon afterwards, taking Cassiano dal Pozzo with him. Poussin became ill with syphilis, but refused to go to the hospital, where the care was extremely poor, and he was unable to paint for months. He survived by selling the paintings he had for a few ecus. Thanks to the assistance of a chef, Jacques Dughet, whose family took him in and cared for him, he largely recovered by 1629, and in 1630 he married Anne-Marie Dughet, the daughter of Dughet.[15] His two brothers-in-law were artists, and Gaspard Dughet later took Poussin's surname.[18]

Cardinal Barberini and Cassiano dal Pozzo returned to Rome in 1626, and by their patronage Poussin received two major commissions. In 1628, with a commission from Cardinal Barberini, he completed his first masterwork, The Death of Germanicus (Minneapolis Institute of Arts). It was partly inspired by the reliefs of the Meleager sarcophagus.[19][20] In February 1628 he received an even more prestigious commission to paint an altarpiece, the Martyrdom of St. Erasmus, for the Erasmus Chapel of the Vatican (now in the Vatican Pinacoteca). This commission was originally given to Pietro da Cortona, but when negotiations broke down between the Vatican and Guido Reni for another painting in the Chapel of the Holy Sacrament, da Cortona replaced Reni and Poussin was given Holy Sacrament commission.[15] Poussin drew upon the original design of Pietro da Cortona but painted the work in his own style.[21]

The Martyrdom of St. Erasmus was the only Vatican commission Poussin received, but it established his reputation as a major painter. With the departure of Vouet from Rome in 1627, Poussin became the most prominent French painter in Rome. Until 1630, he had painted rapidly ("with the fury of a demon", Marino recorded)[22] and produced large numbers of pictures of variable quality. Thereafter, he renounced seeking commissions for large decorative works, which were prestigious but required competitions and came with many restrictions, and concentrated instead on painting for art patrons and collectors, for whom he could work more slowly and develop his own subjects and style. In 1632 he bought a life interest in a small house on Via Paolina for his wife and himself and entered his most productive period.[23]

Apart from Cardinal Barberini, his notable patrons in this period included Cassiano dal Pozzo, for whom he painted the first series of Sacraments; the Chanoine Gian Maria Roscioli, who bought several important works, including The Young Pyrrhus Saved; Cardinal Rospigliosi, for whom he painted the second version of The Shepherds of Arcadia; Cardinal Luigi Omodei, for whom he produced the Triumphs of Flora (c. 1630–32, Louvre); Vincenzo Giustiniani, for whom he painted the Massacre of the Innocents, and the jewel thief and art swindler, Fabrizio Valguarnera, who bought Plague of Ashdod and commissioned The Empire of Flora. He also received his first commissions from France; first from the Marechal de Crequi, the French envoy to Italy, then a commission from Cardinal de Richelieu for a series of Bacchanales.[23]

Return to France (1641–42)

The Miracle of Saint Francis Xavier, 1641, Louvre

The Miracle of Saint Francis Xavier, 1641, Louvre Time defending Truth from the attacks of Envy and Discord, for the study of Cardinal Richelieu, 1642, Louvre

Time defending Truth from the attacks of Envy and Discord, for the study of Cardinal Richelieu, 1642, Louvre Frontispiece for the works of Virgil for the royal printing house, 1641, Metropolitan Museum

Frontispiece for the works of Virgil for the royal printing house, 1641, Metropolitan Museum

As the work of Poussin became well known in Rome, he received invitations to return to Paris for important royal commissions, proposed by Sublet de Noyers, the Superintendent of buildings for Louis XIII. When Poussin declined, Noyers sent his cousins, Roland Fréart de Chambray and Paul Fréart, to Rome to persuade Poussin to come home, offering him the title of First Painter to the King, plus a substantial residence at the Tuileries Palace. Poussin yielded, and in December 1640 he was back in Paris.[24]

The correspondence of Poussin to Cassiano dal Pozzo and his other friends in Rome show that he was appreciative of the money and honors, but he was quickly overwhelmed by a large number of commissions, particularly since he had taken the habit of working slowly and carefully. His new projects included The Institutions of the Eurcharist for the chapel of the Chateau of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, and The Miracle of Saint Francis-Xavier for the altar of the church of the novitiate of the Jesuits. In addition, he was asked to the ceilings and vaults for the Grand gallery of the Louvre, and to paint a large allegorical work for the study of Cardinal Richelieu, on the theme Time Defending Truth from the Attacks of Envy and Discord, with the figure of "Truth" clearly standing for Cardinal Richelieu. He was also expected to provide designs for royal tapestries and the front pieces for books from the royal printing house. He was also subjected to considerable criticism from the partisans of other French painters, including his old friend Simon Vouet. He completed a painting of the Last Supper (now in the Louvre), eight cartoons for the Gobelins tapestry manufactory, drawings for a proposed series of grisaille paintings of the Labors of Hercules for the Louvre, and a painting of the Triumph of Truth for Cardinal Richelieu (now in the Louvre). He was increasingly unhappy with the court intrigues and the overwhelming number of commissions. In the autumn of 1642, when the King and court were out of Paris in Languedoc, he found a pretext to leave Paris and to return permanently to Rome.[25]

Final years in Rome (1642–1665)

Landscape with Orpheus and Eurydice, 1650–51

Landscape with Orpheus and Eurydice, 1650–51

The Four Seasons (Summer), 1660–1664, Louvre

The Four Seasons (Summer), 1660–1664, Louvre

When he returned to Rome in 1642, he found the art world was in transition. Pope Urban VIII died in 1644, and the new Pope, Innocent X, was less interested in art patronage, and preferred Spanish over French culture. Poussin's great patrons, the Barberinis, departed Rome for France. He still had a few important patrons in Rome, including Cassiano dal Pozzo and the future Cardinal Camillo Massimi, but began to paint more frequently for the patrons he had found in Paris. Cardinal Richelieu died in 1632, and Louis XIII died in 1643, and Poussin's Paris sponsor, Sublet de Noyer, lost his position, but Richelieu's successor, Cardinal Mazarin, began to collect Poussin's works. In October 1643, Poussin sold the furnishings of his house in the Tuileries in Paris, and settled for the rest of his life in Rome.[26]

In 1647, André Félibien, the secretary of the French Embassy in Rome, became a friend and painting student of Poussin, and published the first book devoted entirely to his work. His growing number of French patrons included the Abbé Louis Fouquet, brother of Nicolas Fouquet, the celebrated superintendent of finances of the young Louis XIV. In 1655 Fouquet obtained for Poussin official recognition of his earlier title as First Painter of the King, along with payment for his past French commissions. To thank Fouquet, Poussin made designs for the baths Fouquet was constructing at his chateau at Vaux-le-Vicomte.[27]

Another important French patron of Poussin in this period was Paul Fréart de Chantelou, who came to Rome in 1643 and stayed there for several months. He commissioned from Poussin some of his most important works, including the second series of the Seven Sacraments, painted between 1644 and 1648, and his Landscape with Diogenes.[28] In 1649 he painted the Vision of St Paul for the comic poet Paul Scarron, and in 1651 the Holy Family for the duc de Créquy. Landscapes had been a secondary feature of his early work; in his later work nature and the landscape was frequently the central element of the painting.[29]

He lived an austere and comfortable life, working slowly and apparently without assistants. The painter Charles Le Brun joined him in Rome for three years, and Poussin's work had a major influence on Le Brun's style. In 1647, his patrons Chantelou and Pointel requested portraits of Poussin. He responded by making two self-portraits, completed together in 1649.[30]

He suffered from declining health after 1650, and was troubled by a worsening tremor in his hand, evidence of which is apparent in his late drawings.[31] Nonetheless, in his final eight years he painted some of the most ambitious and celebrated of his works, including The Birth of Bacchus, Orion Blinded Searching for the Sun, Landcape with Hercules and Cacus, the four paintings of The Seasons and Apollo in love with Daphné.

His wife Anne-Marie died in 1664, and thereafter his own health sank rapidly. On 21 September he dictated his will, and he died in Rome on 19 November 1665 and was buried in the church of San Lorenzo in Lucina.[32]

Subjects

Each of Poussin's paintings told a story. Though he had little formal education, Poussin became very knowledgeable in the nuances of religious history, mythology and classical literature, and, usually after consulting with his clients, took his subjects from these topics. Many of his paintings combined several different incidents, occurring at different times, into the same painting, in order to tell the story, and the affetti, or facial expressions of the participants, showed their different reactions.[33] Aside from his self-portraits, Poussin never painted contemporary subjects.[34]

Religion

Massacre of the Innocents, 1625–29, Musée Condé, Chantilly

Massacre of the Innocents, 1625–29, Musée Condé, Chantilly_Nicolas_Poussin.jpg) The Seven Sacraments - Ordination, 1647, Louvre

The Seven Sacraments - Ordination, 1647, Louvre The Judgement of Solomon, 1649, Louvre

The Judgement of Solomon, 1649, Louvre

Religion was the most common subject of his paintings, as the church was the most important art patron in Rome and because there was a growing demand by wealthy patrons for devotional paintings at home. He took a large part of his themes from the Old Testament, which offered more variety and the stories were often more vague and gave him more freedom to invent. He painted different versions of the stories of Eliazer and Rebecca from the Book of Genesis and made three versions of Moses saved from the waters. The New Testament provided the subject of one of his most dramatic paintings, "The Massacre of the Innocents", where the general slaughter was reduced to a single brutal incident. In his Judgement of Solomon (1649), the story can be read in the varied facial expressions of the participants.[33]

His religious paintings were sometimes criticized by his rivals for their variation from tradition. His painting of Christ in the sky in his painting of Saint-Francis-Xavier was criticized by partisans of Simon Vouet for having "Too much pride, and resembling the god Jupiter more than a God of Mercy". Poussin responded that "he could not and should not imagine a Christ, no matter what he is doing, looking like a gentle father, considering that, when he was on earth among men, it was difficult to look him in the face".[35]

The most famous of his religious works were the two series called The Seven Sacraments, representing the meaning of the moral laws behind each of the principal ceremonies of the church, illustrated by incidents in the life of Christ. The first series was painted in Rome by his major early patron, Cassiano dal Pozzo, and was finished in 1642. It was viewed by his later patron, Paul Fréart de Chantelou, who asked for a copy. Instead of making copies, Poussin painted an entirely new series of paintings, which was finished by 1647. The new series had less of the freshness and originality of the first series, but was striking for its simplicity and austerity in achieving its effects; the second series illustrated his mastery of the balance of the figures, the variety of expressions, and the juxtaposition of colors.[36]

Mythology and classical literature

The Empire of Flora, 1631

The Empire of Flora, 1631 The Rape of the Sabine Women, c. 1638, Louvre

The Rape of the Sabine Women, c. 1638, Louvre Apollo and Daphne, 1664, Louvre

Apollo and Daphne, 1664, Louvre

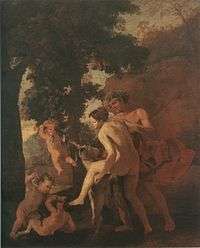

Classical Greek and Roman mythology, history and literature provided the subjects for many of his paintings, particularly during his early years in Rome. His first successful painting in Rome, The Death of Germanicus, was based upon a story in the Annals of Tacitus. In his early years he devoted a series of paintings, full of color, movement and sensuality, to the Bacchanals, colorful portrayals of ceremonies devoted to the god of wine Bacchus, and celebrating the goddesses Venus and Flore. He also created The Birth of Venus (1635), telling the story of the Roman goddess through an elaborate composition full of dynamic figures for the French patron, Cardinal Richelieu, who had also commissioned the Bacchanals.[37] Many of his mythological paintings featured gardens and floral themes; his first Roman patrons, the Barberini family, had one of largest and most famous gardens in Rome. Another of his early major themes was the Rape of the Sabine Women, recounting how the King of Rome, Romulus, wanting wives for his soldiers, invited the members of the neighboring Sabine tribe for a festival, and then, on his signal, kidnapped all of the women. He painted two versions, one in 1634, now in the Metropolitan Museum, and the other in 1637, now in the Louvre. He also painted two versions illustrating a story of Ovid in the Metamorphoses in which Venus mourning the death of Adonis after a hunting accident, transforms his blood into the color of the anemone flower.

Throughout his career, Poussin frequently achieved what the art historian Willibald Sauerländer terms a "consonance ... between the pagan and the Christian world".[38] An example is The Four Seasons (1660–64), in which Christian and pagan themes are mingled: Spring, traditionally personified by the Roman goddess Flora, instead features Adam and Eve in the garden of Eden; Summer is symbolized not by Ceres but by the biblical Ruth.[38]

In his later years, his mythological paintings became more somber, and often introduced the symbols of mortality and death. The last painting he was working on before his death was Apollo in love with Daphne, which he presented to his patron, the future Cardinal Massimi, in 1665. The figures on the left of the canvas, around Apollo, largely represented vitality and life, while those on the right, around Daphne, were symbols of sterility and death. He was unable to complete the painting because of the trembling of his hand, and the figures on the right are unfinished.[39]

Poetry and allegory

Renaud et Armide, 1635

Renaud et Armide, 1635.jpg) Et in Arcadia ego (The Shepherds of Arcadia), second version, late 1630s, Louvre

Et in Arcadia ego (The Shepherds of Arcadia), second version, late 1630s, Louvre A Dance to the Music of Time, 1640, The Wallace Collection, London

A Dance to the Music of Time, 1640, The Wallace Collection, London

Besides classical literature and myth, he drew often from works of the romantic and heroic literature of his own time, usually subjects decided in advance with his patrons. He painted scenes from the epic poem Jerusalem Delivered by Torquato Tasso (1544–1595), published in 1581, and one of the most popular books in Poussin's lifetime. His painting Renaud and Armide illustrated the death of the Christian knight Arnaud at the hands of the magician Armide. who, when she saw his face, saw her hatred turn to love. Another poem by Tasso with a similar theme inspired Tancred and Hermiene; a woman finds a wounded knight on the road, breaks down in tears, then finds the strength through love to heal him.[40]

Allegories of death are common in Poussin's work, One of the best-known examples is Et in Arcadia ego, a subject he painted in about 1630 and again in the late 1630s. Idealized shepherds examine a tomb inscribed with the title phrase, "Even in Arcadia I exist", reminding that death was ever-present.[41]

A fertile source for Poussin was Cardinal Giulio Rospigliosi, who wrote moralistic theatrical pieces which were staged at the Palace Barberini, his early patron. One of his most famous works, A Dance to the Music of Time, was inspired by another Rospigliosi piece. According to his early biographers Bellori and Felibien, the four figures in the dance represent the stages of life: Poverty leads to Work, Work to Riches, and Riches to Luxury; then, following Christian doctrine, luxury leads back to poverty, and the cycle begins again. The three women and one man who dance represent the different stages and are distinguished by their different clothing and headdresses, ranging from plain to jeweled. In the sky over the dancing figures, the chariot of Apollo passes, accompanied by the Goddess Aurora and the Hours, a symbol of passing time.[41]

Landscapes and townscapes

Landscape with Saint John on Patmos (Late 1630s)

Landscape with Saint John on Patmos (Late 1630s)

Landscape with Pyramus and Thisbe (1651)

Landscape with Pyramus and Thisbe (1651) The Death of Sapphira (1654)

The Death of Sapphira (1654)

Poussin is an important figure in the development of landscape painting. In his early paintings the landscape usually forms a graceful background for a group of figures, but later the landscape played a larger and larger role and dominated the figures, illustrating stories, usually tragic, taken from the Bible, mythology, ancient history or literature. His landscapes were very carefully composed, with the vertical trees and classical columns carefully balanced by the horizontal bodies of water and flat building stones, all organized to lead the eye to the often tiny figures. The foliage in his trees and bushes is very carefully painted, often showing every leaf. His skies played a particularly important part, from the blue skies and gray clouds with bright sunlit borders (a sight often called in France "a Poussin sky") to illustrate scenes of tranquility and the serenity of faith, such as the Landscape with Saint John on Patmos, painted in the late 1630s before his departure for Paris; or extremely dark, turbulent and threatening, as a setting for tragic events, as in his Landscape with Pyramus and Thisbe (1651). Many of his landscapes have enigmatic elements noticeable only with closer inspection; for example, in the center of the landscape with Pyramus and Thisbe, despite the storm in the sky, the surface of the lake is perfectly calm, reflecting the trees.[42]

Between 1650 and 1655, Poussin also painted a series of paintings now often called "townscapes", where classical architecture replaces trees and mountains in the background. The painting The Death of Saphire uses this setting to illustrate two stories simultaneously; in the foreground, the wife of a wealthy merchant dies after being chastised by St. Peter for not giving more money to the poor; while in the background another man, more generous, gives alms to a beggar.[42]

Style and method

Bacchanale or Bacchus and Ariadne, 1624–1625, Prado Museum

Bacchanale or Bacchus and Ariadne, 1624–1625, Prado Museum The Triumph of David, c. 1630, Prado Museum

The Triumph of David, c. 1630, Prado Museum The Four Seasons (Spring), c. 1664, The Louvre

The Four Seasons (Spring), c. 1664, The Louvre Triumph of Pan, c. 1635, Pen and ink with wash, over black chalk and stylus, Royal Collection

Triumph of Pan, c. 1635, Pen and ink with wash, over black chalk and stylus, Royal Collection

Throughout his life Poussin stood apart from the popular tendency toward the decorative in French art of his time. In Poussin's works a survival of the impulses of the Renaissance is coupled with conscious reference to the art of classical antiquity as the standard of excellence. Rejecting the emotionalism of Baroque artists such as Bernini and Pietro da Cortona, he emphasized the cerebral.[43] His goal was clarity of expression achieved by disegno or ‘nobility of design’ in preference to colore or color.[44]

During the late 1620s and 1630s, he experimented and formulated his own style. He studied the Antique as well as works such as Titian’s Bacchanals (The Bacchanal of the Andrians, Bacchus and Ariadne, and The Worship of Venus) at the Casino Ludovisi and the paintings of Domenichino and Guido Reni.[45]

In contrast to the warm and atmospheric style of his early paintings, Poussin by the 1630s developed a cooler palette, a drier touch, and a more stage-like presentation of figures dispersed within a well defined space.[12] In The Triumph of David (c. 1633–34; Dulwich College Picture Gallery), the figures enacting the scene are arranged in rows that, like the architectural facade that serves as the background, are parallel to the picture plane.[12] The violence of The Rape of the Sabine Women (c. 1638; Louvre) has the same abstract, choreographed quality seen in A Dance to the Music of Time (1639–40).[12]

Contrary to the standard studio practice of his time, Poussin did not make detailed figure drawings as preparation for painting, and he seems not to have used assistants in the execution of his paintings.[12] He produced few drawings as independent works, aside from the series of drawings illustrating Ovid's Metamorphoses he made early in his career. His drawings, typically in pen and ink wash, include landscapes drawn from nature to be used as references for painting, and composition studies in which he blocked in his figures and their settings. To aid him in formulating his compositions he made miniature wax figures and arranged them in a box that was open on one side like a theatre stage, to serve as models for his composition sketches.[46] Pierre Rosenberg described Poussin as "not a brilliant, elegant, or seductive draughtsman. Far from it. His lack of virtuosity is, however, compensated for by uncompromising rigour: there is never an irrelevant mark or a superfluous line."[47]

Legacy

In the years following Poussin's death, his style had a strong influence on French art, thanks in particular to Charles LeBrun, who had studied briefly with Poussin in Rome, and who, like Poussin, became a court painter for the King and later the head of the French Academy in Rome. Poussin's work had an important influence on the 17th-century paintings of Jacques Stella and Sébastien Bourdon, the Italian painter Pier Francesco Mola, and the Dutch painter Gerard de Lairesse.[48] A debate emerged in the art world between the advocates of Poussin's style, who said the drawing was the most important element of a painting, and the advocates of Rubens, who placed color above the drawing.[49] During the French Revolution, Poussin's style was championed by Jacques-Louis David in part because the leaders of the Revolution looked to replace the frivolity of French court art with Republican severity and civic-mindedness. The influence of Poussin was evident in paintings such as Brutus and Death of Marat. Benjamin West, an American painter of the 18th century who worked in Britain, found inspiration for his canvas of The Death of General Wolfe in Poussin's The Death of Germanicus.[50]

The 19th century brought a resurgence of enthusiasm for Poussin. One of his greatest admirers was Ingres, who studied in Rome and became Director of the French Academy there. Ingres wrote, "Only great painters of history can paint a beautiful landscape. He (Poussin) was the first, and only, to capture the nature of Italy. By the character and taste of his compositions, he proved that such nature belonged to him; so much so that when facing a beautiful site, one says, and says correctly, that it is "Poussinesque".[51] Another 19th-century admirer of Poussin was Ingres' great rival, Eugène Delacroix; he wrote in 1853: "The life of Poussin is reflected in his works; it is in perfect harmony with the beauty and nobility of his inventions...Poussin was one of the greatest innovators found in the history of painting. He arrived in the middle of the school of mannerism, where the craft was preferred to the intellectual role of art. He broke with all of that falseness".[52]

Cézanne appreciated Poussin's version of classicism. "Imagine how Poussin entirely redid nature, that is the classicism that I mean. What I don't accept is the classicism that limits you. I want that a visit to a master will help me find myself. Every time I leave a Poussin, I know better who I am."[52] Cézanne was described in 1907 by Maurice Denis as "the Poussin of Impressionism".[53] Georges Seurat was another Post-Impressionist artist who admired the formal qualities of Poussin's work.[54]

In the 20th century, some art critics suggested that the analytic Cubist experiments of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque were also founded upon Poussin's example.[55] In 1963 Picasso based a series of paintings on Poussin's The Rape of the Sabine Women. André Derain,[56] Jean Hélion,[57] Balthus,[58] and Jean Hugo were other modern artists who acknowledged the influence of Poussin. Markus Lüpertz made a series of paintings in 1989–90 based on Poussin's works.[59]

The finest collection of Poussin's paintings today is at the Louvre in Paris. Other significant collections are in the National Gallery in London; the National Gallery of Scotland; the Dulwich Picture Gallery; the Musée Condé, Chantilly; the Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg; and the Museo del Prado, Madrid.

Gallery

Acis and Galatea, 1629, National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin

Acis and Galatea, 1629, National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin Sleeping Venus with Cupid, 1630, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden

Sleeping Venus with Cupid, 1630, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden Venus, a Faun and Putti, 1630s, The Hermitage Museum, St-Petersburg

Venus, a Faun and Putti, 1630s, The Hermitage Museum, St-Petersburg The Adoration of the Magi, 1633, Dulwich Picture Gallery

The Adoration of the Magi, 1633, Dulwich Picture Gallery.jpg) The Abduction of the Sabine Women, c. 1633–1634, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Abduction of the Sabine Women, c. 1633–1634, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Helios and Phaeton with Saturn and the Four Seasons, c. 1635

Helios and Phaeton with Saturn and the Four Seasons, c. 1635 Diana and Endymion, 1630s, The Detroit Institute of Arts

Diana and Endymion, 1630s, The Detroit Institute of Arts The Birth of Venus,1635 or 1636

The Birth of Venus,1635 or 1636 The Triumph of Pan, 1636, National Gallery, London

The Triumph of Pan, 1636, National Gallery, London_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg) Sacrament of Ordination (Christ Presenting the Keys to Saint Peter) , c. 1636–1640, Kimbell Art Museum

Sacrament of Ordination (Christ Presenting the Keys to Saint Peter) , c. 1636–1640, Kimbell Art Museum Holy Family, c. 1649, National Gallery of Ireland

Holy Family, c. 1649, National Gallery of Ireland The Holy Family with St Elizabeth and John the Baptist, c. 1655, The Hermitage Museum

The Holy Family with St Elizabeth and John the Baptist, c. 1655, The Hermitage Museum Landscape with a Calm, 1650–1651, Getty Center

Landscape with a Calm, 1650–1651, Getty Center The Annunciation, c. 1655–1657, National Gallery, London

The Annunciation, c. 1655–1657, National Gallery, London

See also

- Category:Paintings by Nicolas Poussin

- List of Nicolas Poussin paintings

- Poussinists and Rubenists

References

Citations

- Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- Jones, Daniel (2011). Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (eds.). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.

- His Lives of the Painters was published in Rome, 1672.

- Rosenberg and Temperini, p. 14.

- Rosenberg and Temperini, p. 15.

- Rosenberg and Temperini, p. 16.

- Keazor 2007, p. 12.

- Thompson et al. 1992, p. 7.

- Rosenberg and Temperini, p. 17.

- Wright 1985, p. 250.

- Rosenberg and Temperini, p. 18.

- Brigstocke.

- Chilvers 2009, p. 496.

- Rosenberg and Temperini, pp. 20–22.

- Rosenberg and Temperini, p. 22.

- In a census of 1624 (Friedlaender)

- The British Museum: Collection online

- Blunt 1958, p.55.

- The Meleager sarcophagus seen by Poussin is that now in the Capitoline Museums.

- Rosenberg and Temperini, pp. 28–29.

- Blunt 1958, pp. 55, 85–88.

- Rosenberg and Temperini p. 30

- Rosenberg and Temperini p. 30.

- Rosenberg and Temperini, p. 31.

- Rosenberg and Temperini, pp. 33–38.

- Rosenberg and Temperini, pp. 38–40.

- Rosenberg and Temperini, p. 42.

- Wright 1985, p. 211.

- Rosenberg and Temperini, pp. 42–45.

- Rosenberg and Temperini, pp. 44–45.

- Wright 1985, p. 254.

- Rosenberg and Temperini, pp. 48–49.

- Rosenberg and Temperini, pp. 51–53.

- Carrier, David. "Poussin's Cartesian Meditations: Self and Other in the Self-Portraits of Poussin and Matisse". Notes in the History of Art, vol. 15, no. 3, 1996, pp. 28–35.

- Félibien cited by Rosenberg and Temperini, p. 32.

- Rosenberg and Temperini, p. 71.

- Oberhuber, Konrad (1988). Poussin; The Early Years in Rome: The Origins of French Classicism. New York: Hudson Hills Press.

- Sauerländer 2016.

- Rosenberg and Temperini, pp. 94–95.

- Rosenberg and Temperini, pp. 94–100.

- Rosenberg and Temperini, pp. 101–102.

- Rosenberg and Temperini 1994, pp. 109–127.

- Wright 1985, pp. 49–50.

- Pace.

- Blunt 1958, pp. 54–59.

- Wright 1985, p. 68.

- Rosenberg, Pierre. "Poussin Drawings from British Collections. Oxford". The Burlington Magazine, vol. 133, no. 1056, 1991, pp. 210–213.

- Wright 1985, p. 11.

- Janson, H.W. (1995) History of Art. 5th edn. Revised and expanded by Anthony F. Janson. London: Thames & Hudson, p. 604. ISBN 0500237018

- Facos 2011, pp. 32, 53.

- Rosenberg and Temperini 1994, p. 149.

- Rosenberg and Temperini 1994, pp. 147–148.

- Russell 4 November 1990.

- Clay, Jean. (1973). Impressionism. Paris: Hachette Réalités. p. 273. ISBN 2010066235

- Wilkin.

- Cowling, Elizabeth; Jennifer Mundy (1990). On Classic Ground: Picasso, Léger, de Chirico and the New Classicism 1910–1930. London: Tate Gallery. pp. 93–93. ISBN 1-854-37043-X.

- Hélion, Jean (2004). Jean Hélion. London: Paul Holberton Pub. pp. 20–21. ISBN 1-903470-27-7

- Rewald, Sabine (1984). Balthus. New York: Harry N. Abrams, publ. p. 82. ISBN 0870993666.

- Keazor 2007, p. 8.

Sources

- Blunt, Anthony (1958). Nicholas Poussin. Phaidon.

- Brigstocke, Hugh. "Poussin, Nicolas". Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Web. (subscription required)

- Chilvers, Ian (2009). The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 019953294X.

- Facos, Michelle (2011). Introduction to Nineteenth-Century Art. New York: Routledge. ISBN 1136840710.

- Friedländer, Walter (1964). Nicolas Poussin: A New Approach. New York: Abrams. 1964. OCLC 2922468

- Keazor, Henry (2007). Nicolas Poussin 1594–1665. Taschen, Hong Kong, Köln, London et al. ISBN 3-8228-5319-4/ISBN 978-3-8228-5319-1

- Kimmelman, Michael, "When Poussin Drew for Himself", The New York Times", 23 February 1996. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- Pace, Claire, "Disegno e colore". Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Web. (subscription required)

- Russell, John (4 November 1990). "Art View; Back and Forth Between Poussin and Cezanne". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- Rosenberg, Pierre and Temperini, Renaud, Poussin- "Je n'ai rien négligé", (in French), 1994, Paris, Gallimard, ISBN 2-07-053269-0

- Sauerländer, Willibald (14 January 2016). "Happy Anniversary, Nicolas Poussin". The New York Review of Books. 63 (1): 46, 48.

- Standring, Timothy. "Poussin's Erotica", Apollo (magazine), 2009-03-01. Retrieved 28 May 2009.

- Thompson, James, Poussin, N., & Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.) (1992). Nicolas Poussin. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. 50 (3), pp. 1, 3–56, OCLC 27763575

- Wilkin, Karen (January 1995). "The 'High Art' of Nicolas Poussin". The New Criterion on line. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- Wright, Christopher (1985). Poussin Paintings: A Catalogue Raisonné. New York: Hippocrene. ISBN 0-87052-218-3

Further reading

- Blunt, Anthony (1966). The Paintings of Nicolas Poussin: A Critical Catalogue. London: Phaidon. OCLC 349831

- Blunt, Anthony (1967), Nicolas Poussin, Pallas Athene, ISBN 1-873429-64-9

- Cropper, Elizabeth and Charles Dempsey (1995). Nicolas Poussin: Friendship and the Love of Painting. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995. ISBN 978-0-691-05067-6

- Keazor, Henry (1998). Poussins Parerga. Quellen, Entwicklung und Bedeutung der Kleinkompositionen in den Gemälden Nicolas Poussins. Schnell & Steiner, Regensburg. ISBN 3-7954-1146-7

- Mérot, Alain (1990), Nicolas Poussin, Abbeville Press, ISBN 1-55859-120-6

- Serres, Michel (1995). Genesis (Grasset). Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-08435-7. OCLC 31937184

- Thuillier, Jacques (1995). Nicolas Poussin. Paris: Flammarion. ISBN 2-08-012440-4

- Thuillier, Jacques (1995). Poussin before Rome: 1594–1624, translated from the French by Christopher Allen (1995). London, New York and Chicago: Richard L. Feigen & Co. ISBN 1-873232-03-9

- Barker, Naomi Joy (2000). "'Diverse Passions': Mode, Interval and Affect in Poussin's Painings". Music in Art: International Journal for Music Iconography. 25 (1–2): 5–24. ISSN 1522-7464.

- Unglaub, Jonathan (2006). Poussin and the Poetics of Painting: Pictorial Narrative and the Legacy of Tasso. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0-521-83367-7

- Tina Mansueto, Nicolas Poussin, Il Rinascimento arcadico del XVII secolo, Paolo Loffredo iniziativeditoriali, Napoli, 2016, ISBN 9788899306304.

Exhibitions

- Paris 1960. "Poussin peintre: retrospectif". Galvanized the renewed interest in Poussin.

- Fort Worth 1988. "Poussin: The Early Years in Rome: The Origins of French Classicism".

- Paris 1994. "Nicolas Poussin 1594–1665" Grand Palais.

- New York City 2008. "Poussin and Nature: Arcadian Visions". Metropolitan Museum of Art; Poussin's landscapes.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nicolas Poussin. |

- 61 paintings by or after Nicolas Poussin at the Art UK site

- A 16min educational film about Nicolas Poussin

- NicolasPoussin.org – 92 works by Nicolas Poussin

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Julia L. Valiela, "The Baptism of Christ, by Nicolas Poussin (cat. 773)," in The John G. Johnson Collection: A History and Selected Works, a Philadelphia Museum of Art free digital publication.