Port Miami Tunnel

The Port of Miami Tunnel (also State Road 887) is a 4,200 feet (1,300 m)[3] bored, undersea tunnel in Miami, Florida. It consists of two parallel tunnels (one in each direction) that travel beneath Biscayne Bay, connecting the MacArthur Causeway on Watson Island with PortMiami on Dodge Island. It was built in a public–private partnership between three government entities—the Florida Department of Transportation, Miami-Dade County, and the City of Miami—and the private entity MAT Concessionaire LLC, which was in charge of designing, building, and financing the project and holds a 30-year concession to operate the tunnel.[4][5][6]

Watson Island entrance | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Location | Miami, Florida |

| Route | |

| Start | Watson Island |

| End | Dodge Island |

| Operation | |

| Work begun | May 24, 2010 |

| Constructed | Bouygues Construction |

| Opened | August 3, 2014 |

| Owner | FDOT |

| Operator | MAT Concessionaire, LLC |

| Traffic | Automotive |

| Toll | None |

| Vehicles per day | 7000 (August 2014)[1] |

| Technical | |

| Length | 4,200 feet (1,300 m) |

| No. of lanes | 2 (per tunnel) |

| Operating speed | 35 miles per hour[2] |

| Highest elevation | Sea level |

| Lowest elevation | −120 feet (−37 m)[2] |

| Tunnel clearance | 15 feet (4.6 m) |

| Width | 43 feet (13 m) per tunnel |

| Grade | 5%[2] |

| www | |

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

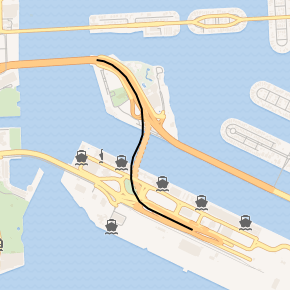

SR 887 highlighted in black | ||||

| Route information | ||||

| Maintained by FDOT | ||||

| Existed | 2014–present | |||

| Major junctions | ||||

| South end | Port Boulevard on Dodge Island | |||

| North end | ||||

| Highway system | ||||

| ||||

The project was approved after decades of planning and discussion in December 2007, but was temporarily cancelled a year later. Construction began in May 2010. The tunnel boring machine began work in November 2011 and completed the second tunnel in May 2013.[7] The tunnel was opened to traffic on August 3, 2014.[8] In the first month after opening, the tunnel averaged 7,000 vehicles per day, and nearly 16,000 vehicles now travel to the port on a typical weekday.[1]

History

The idea of a tunnel connecting the Port of Miami to Watson Island was first conceived in the 1980's as a way to reduce traffic congestion in downtown Miami. Prior to the tunnel's opening, the only route for PortMiami traffic was a two-lane drawbridge that emptied out into the streets of downtown Miami. The heavy traffic was considered detrimental to the economic growth of downtown, and a planned project to expand the port's capacity threatened to increase the volume of trucks coming through. These problems were alleviated, but not solved, by the construction of a six-lane elevated bridge, which still stands, in the early 1990s.[9] The issues would be remedied by the construction of the tunnel, allowing traffic to move between PortMiami and the MacArthur Causeway (which connects to Interstate 95 via I-395) without traveling through downtown.

Federal funding for a preliminary study into the tunnel proposal was included in the controversial 1987 highway bill which was vetoed by President Ronald Reagan, who complained that the bill was a "pork-barrel" project.[10][11] Although the veto was overridden, the tunnel proposal fell by the wayside. It was not until 2006 that the tender for the tunnel project was ready to be launched, and in December 2007 the project was approved by the City Commission.[12] However, the economic crisis resulted in a cancellation of the project in December 2008 by one of the sponsors, Babcock & Brown, and the State of Florida.[13] Despite this, in April 2009, following intense lobbying by Miami-Dade Mayor Carlos Alvarez,[14] to avoid a new tender that would delay even further the start of construction, the project was reinstated. Port director Bill Johnson has also played a key role in supporting the Port of Miami infrastructure projects,[15] as well as developing a free-trade pact with Colombia. Altogether, the port infrastructure projects had an estimated cost of around two billion dollars.[16]

Prior to 2008, the project had been estimated at a total cost of $3.1 billion USD,[17] however the revised project has an estimated cost of $1 billion USD (The difference in estimates partially due to differences in previous tunnel designs).[18] Financial closing on the project was reached in October 2009.[19] Miami-Dade County allegedly contributed $402 million, the city of Miami $50 million, and the state $650 million to build, operate and maintain it.[14] Those contributions are spread during construction and operation of the tunnel project. During construction, 90% of the funds are provided by the private sector. Of the estimated $1 billion total project cost, $607 million would go to design and construction, $195.1 million to financing, $59.6 million to insurance and maintenance during construction, $41.2 million to reserves, and $209.8 million for state development cost.[20]

Overview

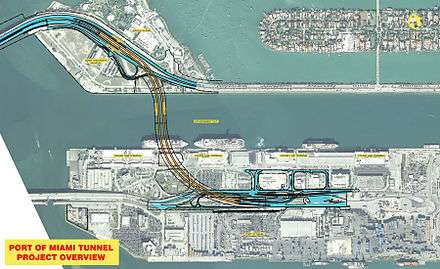

The Port of Miami Tunnel project involved the design and widening of the MacArthur Causeway by one lane in each direction leading up to the tunnel entrance, the relocation of Parrot Jungle Trail, and the reconstruction of roadways on Dodge Island. The tunnel itself has two side by side tubes carrying traffic underneath the cruise ship channel of the Government Cut shipping lane. Jacobs Engineering Group was responsible for the design of the roadways, Langan Engineering & Environmental Services was the geotechnical engineer, and Bouygues was the prime contractor for the tunnel project itself. Chosen due to their key involvement in the construction of the Channel Tunnel, a major tunnel in Europe, the selection of Bouygues was also met with controversy and protested by the Cuban exile community in Miami, due to the company's involvement with locally opposed construction projects in Cuba.[13]

The project connects the east/west Interstate 395 (I-395)/State Road 836, which terminates into State Route A1A at the Miami city limit on the MacArthur Causeway, as well as Interstate 95, directly to PortMiami.[21] The port was previously only connected to the mainland by Port Boulevard, which is accessed by crossing U.S. Route 1 (Biscayne Boulevard) and traveling through downtown.[19] The project also includes roadway improvements to the connection between I-395 and State Road 836,[22] also known as the Dolphin Expressway, at Interstate 95. The tunnel will allow heavy trucks to bypass the congested Downtown Miami area, which is considered to be especially crucial with the large increase in trade traffic expected to be created by the Deep Dredge Project and the enlargement of the Panama Canal. Projected to eventually carry 26,000 vehicles a day under Government Cut through its twin two-lane tunnels,[23] the top of the tunnels lie over 60 feet (18.3 m) below the seabed. The project created nearly 1,000 jobs as of 2011, with 70% reported as local;[24][25][26] project executives promised that many of the construction jobs would go to local contractors.[27] Along with the related Deep Dredge and Panama Canal Expansion, over 30,000 jobs are expected to be created in the long run.[28]

Before completion of the tunnel, in 2009, nearly 16,000 vehicles travelled to and from PortMiami through downtown streets each weekday. Truck traffic made up 28% (or 4,480) of this number (Source: 2009 PB Americas Traffic Study). In 2010 it was estimated that around 19,000 vehicles traveled to the port daily but that only 16% were trucks.[9] Existing truck and bus routes restricted the port's ability to grow, driving up costs for port users and presenting safety hazards. They were also thought to congest and limit redevelopment of the northern portion of Miami's Central Business District.[26]

The Port of Miami Tunnel includes providing a direct connection from the Port of Miami to highways via Watson Island to I-395 and, along with the deep dredge, keeping the Port of Miami, the County's second largest economic generator (after Miami International Airport), supporting over 11,000 jobs directly with an average salary of $50,000,[29] a competitive player in international trade.[15] The Port of Miami provides 176,000 jobs, $6.4 billion in wages and $17 billion in economic output. (Source: 2007 Port of Miami Economic Impact Study).

Public-private partnership (PPP)

The tunnel project is a public-private partnership (PPP or P3), designed to transfer the responsibility to design, build, finance, operate, and maintain the project to the private sector. Ten banks, BNP Paribas, Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria, RBS Citizens, N.A., Banco Santander, Bayerische Hypo, Calyon, Dexia, ING Capital, Societe Generale, and WestLB, will provide the senior debt financing for the project,[19] which totals $341.5 million.[30] The project attracted three bidding consortia. Under the concession agreement, FDOT will make milestone payments to the concessionaire (Miami Access Tunnel) during the construction period, upon the achievement of contractual milestones. 90% of Miami Access Tunnel's equity is provided by Meridiam Infrastructure Miami LLC (Luxembourg based Meridiam SARL); the remaining 10% by France's Bouygues Travaux Publics SA, operating as Dragages Concession Florida Inc.[19] The Port of Miami Tunnel Project was one of the first P3s in Florida, and the first availability-based P3 deal in the US,[31] after the Interstate 595 (I-595) renovation project in Broward County.[32]

When construction is completed, FDOT will make availability payments to the concessionaire. These payments will be contingent upon actual lane availability and service quality: if the tunnel is closed or the road is in bad condition, part or all of the payment for that period may be withheld.[30] The tunnel will be turned over to FDOT in first-class condition at the end of the contract in October 2044, thirty years after its completion.[20] Maintenance costs over this 30-year period are expected to total around $200 million.[33] Unlike many similar public-private partnerships, the tunnels will not have a toll.[19]

The originally scheduled June 2014 opening was delayed due to several mechanical problems, including leaky pipes, broken exhaust fans due to sudden vibrations, and failing bolts. The general contractor Bouygues was fined $115,000 for every day that the tunnel was not open, losing millions of dollars. The tunnel was officially opened to commercial and private traffic on August 3, 2014.

Criticism

According to the Miami Herald the financing structure of the plan is notable for the amount of financial risk taken by the builders in return for the long term concession on the tunnel.[13] Opposition to the project states that it is a waste of taxpayer money, and may become Miami's Big Dig, the nickname of a tunnel megaproject in Boston, which was a $4 billion project that ended up costing $22 billion in cost overruns. Many believe that the Port of Miami Tunnel Project will be likely to have similar cost overruns,[34] even though the Secretary of the Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) promised that the project would finish on time and without overruns.[35] They also state that truck traffic is not a problem in Downtown, and that since 1991 car and truck traffic had reduced significantly.[36]

Downtown business owners have referred to it as the "tunnel to no where," stating that no one will use it. In 1992, 32,000 vehicles entered the port daily, a number which later dropped to nearly half that, but had once again risen to around 19,000 by 2011.[9] It has been regarded as a boondoggle project by those who oppose it, stating that the city can't afford it. In fact, the city did have difficulty providing its $50 million portion of the funding for the project.[37][38] Some believe it may create traffic problems on the MacArthur Causeway; environmentalists worry about the potentially negative impact the construction could have on the Biscayne Bay.[39] An ominous foreshadowing of cost overruns, Miami Access Tunnel requested money from a $150 million reserve fund in July 2011 for the unexpected need to grout the limestone beneath the surface so that the tunnel boring machine cuts more smoothly. This request alarmed new Miami-Dade Mayor Carlos A. Giménez when it was brought up at his first commissioners meeting as mayor on July 7.[40]

The contractor stated that they will continue without the additional requested money if FDOT denies it, but it may end up as a court case as the contractor seeks it later.[41] On July 19, the FDOT denied the request for more money to the contractor, stating that the geological issue cited was not as extensive as MAT claimed.[42]

Benefits/related projects

Although there is great speculation that the Port of Miami Tunnel project is both unnecessary and a waste of taxpayer dollars, it is expected to have positive benefits in the long run which coincide with several other related projects predicted to increase its traffic, many, such as the Port of Miami Deep Dredge Project and Panama Canal expansion, slated to be finished in 2015 and 2016, respectively. The port has gone through several expensive projects throughout its history, and many have been seen as beneficial to the economic growth of the Greater Miami area in the long run, such as in the 1950s when the deteriorating Port of Miami, then located in the mainland in downtown, was moved to its current home, the man-made Dodge Island.[43] The current port director of the Port of Miami Bill Johnson states that these new port infrastructure projects should be able to double the port's container capacity over the next decade.[44] Miami City Commissioner Marc Sarnoff stated that "This is the best public works project ever."[24] A strong trade industry is also considered to be a vital sign of a good and improving economy.[45]

Cruise traffic

In addition to the expected increase in cargo traffic, the Port of Miami recently stated that October 2010 was its busiest October ever for cruise vacations. The port had a record 346,513 cruise passengers that October, up 29% from October 2009. This follows a record year in cruise traffic, with 4.15 million cruise passengers in the 12 months that ended in September.[46] This is partially due to the arrival of new cruise ships such as the Norwegian Epic, as well as the cruise line Costa Cruises.[47] Despite this, the Port of Miami has recently been losing cruise and cargo traffic to nearby Port Everglades in Fort Lauderdale. In 2010, Royal Caribbean Cruise Lines, which is headquartered in Miami, chose Port Everglades as home for its new cruise ships, Oasis of the Seas and Allure of the Seas,[48] currently the largest cruise ships in the world.

As for cargo traffic, truckers state that despite the longer miles, they can make more trips per day at Port Everglades. Also, they blame the port itself for this, not the Downtown traffic.[36] They state that at Port Everglades, they can make three to four runs a day, versus Port of Miami where "you're lucky if you get in two," states truck driver Alejandro Arrieta, due to waiting time at the port, which is often several hours.[9] Port Everglades also has major redevelopment plans underway that includes its own deep dredging to a 50-foot (15 m) depth;[49] they also claim to have surpassed the Port of Miami, which has long been known as the "Cruise Capital of the World" as well as the "Cargo Gateway to the Americas," in both cruise traffic and cargo tonnage handled.

Railroad access

The Port of Miami was also recently awarded a federal grant as part of the Transportation Investment Generating Economic Recovery (TIGER) program to restore a connection between the Florida East Coast Railway's yard in Hialeah and the Port of Miami, directly connecting the port to rail networks across the United States,[50] as well as re-establish the port's on-dock rail capability (loading and unloading directly between ships and trains).[51] The railroad bridge connecting the Port of Miami to the mainland was damaged by Hurricane Wilma in 2005, at which time service was suspended, and the bridge remained closed for well over a decade.[52] Rail service to the port was restored by 2014.[53] The rail project is part of another element of increasing PortMiami's capacity; an inland intermodal center to be built near the airport known as Flagler Logistics Hub, which was planned to be built on 300 acres of land in Hialeah.[54]

Opposition to the railroad line returning to service included that it would be as much of a problem to downtown traffic as the container trucks and that the noise would be a disturbance to nearby residents. As with before, however, trains are occasional and reserved for specialty loads, such as oversized loads and hazardous materials, which will be banned from the tunnel. It was also stated that the trains, which will be able to go up to 30 mph on the newly renovated line versus the old limit of 5 mph,[55] will be able to cross Biscayne Boulevard in 90 seconds.[56] The current plan is for the line to be strictly for intermodal services, with the project including a rail yard and station at the port, however, in the future a passenger station may be added.[57]

Downtown congestion

Another major benefit of the tunnel will be the redirecting of the large number of vehicles (nearly 16,000 daily; 2009 estimate),[58] many of them container trucks and cruise buses, that cross Biscayne Boulevard (US 1) at NW 5th Street (Port Boulevard), using level streets, such as Northeast 1st Avenue,[24] which for years were the only way to access the port.[59] Along with the capacity of the port, the amount of truck traffic could double after the completion of the numerous port projects.[44] Additionally, the Port Boulevard entrance to the port is closed at night, concentrating all truck traffic during the day. This traffic creates congestion and presents a danger to pedestrians and bicyclists. Traffic is also considered to be a harm to Miami's northern central business district, reducing its ability to grow, including Miami's new Arts & Entertainment District, valued at over $12 billion.[26]

The developers for a once planned project for the north side of downtown, known as Miami City Square, stated that the heavy truck traffic and congestion in that area was a "grave concern."[60] The Omni Community Redevelopment Agency used a $50 million loan from Wachovia to donate towards financing the tunnel construction.[61] Resorts World Miami by Genting Group and Miami World Center are two proposed major development planned for the area where congestion is a concern.[62]

Additionally, the population of Downtown Miami nearly doubled from 2000 to 2010, and is expected to increase by several thousand more in the current decade, largely due to many new high rise condo developments in the downtown area adding thousands of housing units which will benefit from having the tunnel.[18] Although traffic and port activity has declined since the early 1990s, losing some of it to the nearby Port Everglades, which overtook Port of Miami in 2007 as Florida's largest cargo port,[9] the port is likely to see a large shift in the other direction after it becomes one of few deep water ports in the United States able to handle the New Panamax ships by 2016. Within the first month of opening, it was reported that congestion in the downtown area had eased.[63]

It was estimated that 46% to 80% of the passenger vehicles, many of which are shuttle buses and taxis and make up nearly three quarters of the total port traffic will use the tunnel after it was completed.[58]

Deep Dredge/Panama Canal expansion

The timing of the tunnel's construction and opening coincides with PortMiami Deep Dredge Project that will see the port dredged deeper to accommodate larger ships expected following the completion of the Panama Canal expansion, now expected to be completed in 2016 (previously 2014).[64] This will allow much larger ships, known as New Panamax, which will have a capacity of more than double that of Panamax ships to traverse the canal. This is predicted to cause a major increase in the Port of Miami's cargo traffic, which would overwhelm the intersection of Port Boulevard and Biscayne Boulevard without the tunnel. In 2009, 870,000 trucks moved cargo in and out of the port; and port officials estimate that that number will increase to around 1.4 million when larger ships start arriving.[65] In 2010, about 800,000 TEU's were moved through the port, and port director Bill Johnson said that with the right marketing to major shippers, that number should double by 2020.[66] Currently, the largest cargo ships that dock at the port have a capacity of around 4,200 TEU's (Twenty-foot Equivalent Units). After the canal expansion and port dredging, ships as large as 7,500 to 8,500 TEU's will be able to dock there.[65]

Construction

Work on the Port of Miami Tunnel project began on Watson Island and Dodge Island, including work on the MacArthur Causeway, in May 2010.[67] Groundbreaking on the construction project was unannounced and considered secret, as the groundbreaking was scheduled for June 2010,[6] but actually took place on May 24, 2010,[68] without ceremony.

The tunnel boring machine was built in Germany and had to be re-assembled in Florida after arriving in crates on the 168 metres (551 ft)[69] cargo ship Combi Dock 1[70] on Thursday, June 23, 2011,[71][72] and being assembled in the median of the causeway[73] where the construction is taking place. Both directions of the MacArthur Causeway have remained open during the assembly of the machine except for nighttime lane closures and delays on the westbound side.[74]

The machine, which weighs more than 2,500 tons, was assembled in a 65-foot (20 m) deep pit known as the launching pad located in between two concrete walls in the median of the causeway, which only left a 42-foot (13 m) cutter visible from the road.[75] According to NBC Miami, as of June 2011, 899 jobs had been created by the project, with over 70% being from the 305 area code (Miami-Dade County).[24] The construction is projected to take 47 months, with the tunnel being finished in 2014.[13] The French firm Bouygues Construction has been put in charge of operating the tunnel boring machine, which was nicknamed "Harriet" in July 2011 after a naming competition was sponsored by MAT and the FDOT, and carried out by the Girl Scout Council of Tropical Florida.[76]

The tunnel boring machine was longer than a football field at 540 feet (160 m) long,[33] and over 40 feet (12 m) in diameter. It was used to bore two side by side 43 feet (13 m) diameter tunnels, one for each direction, each 3,900 feet (1.1 km) long.[77] The tunnel boring machine itself cost $45 million and was custom built for the Port of Miami Tunnel Project by the German firm Herrenknecht.[25] No explosives are said to be used on the construction of the tunnel.[22] Drilling of the tunnel itself commenced in mid-November 2011, with the drilling machine beginning work on the Watson Island tunnel entrance.[78]

The first tunnel connecting Watson Island and the Port of Miami was completed in August 2012.,[79] and the second tunnel was completed on May 9, 2013, as "Harriet" emerged back on Watson Island, where digging had commenced in 2011.[80] The roadway construction should finish for an opening on May 15, 2014.[33] The MacArthur Causeway, which currently has three traffic lanes in each direction and a sidewalk on the eastbound side, will be widened to four 12-foot (3.7 m) wide traffic lanes with a ten-foot inner and outer shoulder, as well as a six-foot sidewalk.[81]

The tunnel was officially opened to commercial and private traffic on August 3, 2014, after minor mechanical delays pushed back the originally scheduled June 2014 opening date. The general contractor Bouygues was fined $115,000 for every day that the tunnel was not open, losing millions of dollars.

Controversies

In March 2011, one of the sub contractors of Bouygues fell under criticism for the dumping of tunnel fill on sensitive wetlands on Virginia Key. They were supposed to be dumping the fill on Virginia Key on the degraded northwest side, but were found dumping it 80 to 100 yards (73.1 to 94.5 m) from the designated spot,[82] where they damaged wetlands and killed about 40 mangrove trees with a piece of equipment that got stuck.[83] The intention was that they would be allowed to put 55,000 cubic yards (42,050.5 m3) of fill there provided that they use it to build a berm to block the view of Virginia Key's sewage water treatment plant.[84] The fill that was dumped on Virginia Key was mainly rock and soil from road construction and site preparation on Watson Island and not from tunnel boring, which environmentalists object being put on Virginia Key as it may not be as clean.[75] The north point of Virginia Key is one of the last remaining undeveloped areas near the Miami downtown area and has been recently restored as it was previously used as a dumping site for the infill from the Rickenbacker Causeway, Miami Marine Stadium, and Norris Cut.[85]

One other potential infill site that was briefly suggested is an inlet located between Bicentennial Park and the American Airlines Arena on the mainland in downtown, where Miami-Dade County was conducting a study on the effects it would have.[86] This proposal was quickly retracted after public outcry due to the fact that the currently closed off waterfront lot, known as "Parcel B," is slated to soon be a long anticipated public park.[87] There has also been minor controversy over speculation that a yacht allegedly owned by Bouygues may have been bought with public money. A Bouygues spokesperson denied this claim.[88] The owner of the seaplane base on Watson Island has accused the tunnel builders of trespassing for storing equipment on his property as well as for using the road that passes through his property. FDOT and city officials said the use of the land is permitted.[89]

See also

- Port of Miami Deep Dredge Project

- New Panamax

- Panama Canal expansion project

- Transportation in South Florida

References

- Lincoff, Nina (September 24, 2014). "Port tunnel traffic grows". Miami Today. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- Chardy, Alfonso (May 17, 2014). "Decades after conception, Miami has a port tunnel". Miami Herald. Retrieved June 6, 2014.

- "Port of Miami Tunnel". fdotmiamidade.com. Florida Department of Transportation. Retrieved August 24, 2014.

- "Public Private Partnership". portofmiamitunnel.com. Florida Department of Transportation. Retrieved August 24, 2014.

- "General FAQ". portofmiamitunnel.com. Florida Department of Transportation. Retrieved August 24, 2014.

- Alfonso Chardy (April 17, 2010). "Port of Miami tunnel project on track for June start". Miami Herald. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- "Project History" (PDF). Florida Department of Transportation. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- Newland, Maggie (August 2, 2014). "Tunnel To PortMiami Opening Sunday Morning". WFOR-TV. Retrieved August 3, 2014.

- Erik Maza (June 2, 2010). "Port Of Miami Tunnel Project Could Be South Florida's Big Dig". Miami New Times. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- Pat Burson, Larry Lipman (April 1, 1987). "Fate of Miami tunnel hangs on today's Senate vote". The Palm Beach Post. Retrieved June 29, 2011.

- Davis, Jeff. "30 Years Ago This Week: Reagan’s 1987 Highway Bill Veto", Eno Transportation Weekly, Eno Center for Transportation, March 27, 2017.

- Julia Neyman and Oscar Pedro Musibay (December 13, 2007). "Miami OKs Marlins' stadium, port tunnel". South Florida Business Journal. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- Larry Lebowitz (January 15, 2008). "Planned Miami port tunnel: Can we dig it?". Miami Herald. Retrieved January 15, 2008.

- WPLG-TV (April 16, 2009). "Port Of Miami Tunnel Project Revived". Archived from the original on September 26, 2011. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- Miami Dade County (July 13, 2010). "City-County team up to secure federal funding for Port of Miami Deep Dredge Project". MiamiDade.gov. Archived from the original on September 5, 2010. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- Jose Perez Jones (March 20, 2011). "Miami needs Colombia free-trade pact". Miami Herald. Archived from the original on April 8, 2011. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- "Port of Miami tunnel". Critical Miami. 2005. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- "Florida DOT Mulls Bids on $1-Billion Miami Tunnel Job". Engineering News-Record. 2007. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- Shelly Sigo (October 19, 2009). "Mimai Tunnel Reaches Closure". The Bond Buyer. Retrieved April 5, 2011.

- "Case Studies-Port of Miami Tunnel". Federal Highway Administration. 2010. Archived from the original on January 17, 2011. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- "Port of Miami Cargo". Edward Redlich. October 14, 2010. Retrieved April 6, 2011.

- Hank Tester (April 2, 2010). "Actual Work Spotted at Port Tunnel Project". NBC Miami. Archived from the original on March 13, 2012. Retrieved April 1, 2011.

- "Video: Animation showing what the tunnel would look like". Miami Herald. January 15, 2008. Retrieved January 15, 2008.

- Hank Tester (June 20, 2011). "Port of Miami Tunnel Dig to Get Into High Gear". NBC Miami. Retrieved June 22, 2011.

- Risa Polansky (July 8, 2010). "Port of Miami tunnel project is indeed a big bore". Miami Today News. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- Alyce Robertson (May 25, 2010). "Miami can't afford to have Port of Miami tunnel delayed". Miami Herald. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- Hank Tester (September 1, 2010). "Port of Miami Tunnel Digging Up Local Jobs". NBC Miami. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- "A Man, A Plan, A Tunnel". TransportationNation. March 17, 2011. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved April 9, 2011.

- Miami Herald Editorial (July 14, 2011). "Ready to rake in the big bucks". Miami Herald. Archived from the original on August 11, 2011. Retrieved July 16, 2011.

- Chrissy Mancini Nichols (March 21, 2011). "PPP Profiles:Port of Miami Tunnel". Metropolitan Planning Council. Retrieved March 31, 2011.

- "Miami Tunnel PPP-full deal analysis". Project Finance. October 23, 2009. Retrieved April 5, 2011.

- "Port of Miami Tunnel: Digging deep". Project Finance. November 19, 2009. Retrieved April 5, 2011.

- Ashley Hopkins (April 13, 2011). "Monster boring machine from Germany to dig Port of Miami tunnels". Miami Today. Retrieved April 13, 2011.

- Felipe Azenha (June 2, 2010). "Is the Port of Miami Tunnel Our Big Dig or OurTunnel to Nowhere?". Transit Miami. Archived from the original on July 1, 2011. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- "Work on the Port of Miami tunnel gets under way". WSVN-TV. June 11, 2010. Retrieved April 4, 2011.

- Erik Maza (June 3, 2010). "Port of Miami Tunnel is a waste of taxpayer money". Miami New Times. Retrieved March 31, 2011.

- "Miami Port Tunnel threatened again as SEC orders Miami to turn over its financial books". South East Shipping News. December 12, 2009. Retrieved July 21, 2011.

- "Letters to the Editor". Miami Herald. June 23, 2011. Retrieved July 21, 2011.

- Francisco Alvarado (May 24, 2011). "Five Reasons Carlos Gimenez Is The Wrong Man For The Job". Miami New Times. Retrieved May 24, 2011.

- "New Mayor attends first commission meeting". WSVN-TV. July 7, 2011. Retrieved July 24, 2011.

- Alfonso Chardy and Martha Brannigan (July 7, 2011). "Firm building Miami tunnel seeks more money months before starting to drill". Miami Herald. Archived from the original on August 10, 2011. Retrieved July 7, 2011.

- Alfonso Chardy (July 19, 2011). "Florida officials deny reserve funds for Port of Miami tunnel builders". Miami Herald. Retrieved July 21, 2011.

- Andrew D. Melick (December 12, 2010). "How much should Seaport spend?". Miami Herald. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- "USA: Port of Miami Deep Dredge Project to Double its Cargo Capacity". Dredging Today. November 26, 2010. Retrieved April 1, 2011.

- Marilyn Bowden (May 26, 2011). "Outlook for small business financing is becoming brighter". Miami Today. Retrieved May 29, 2011.

- Doreen Hemlock (December 21, 2010). "Port of Miami had busiest October ever for cruises". Sun Sentinel. Archived from the original on December 26, 2010. Retrieved March 31, 2011.

- "Cruise traffic soars at Port of Miami". South Florida Business Journal. October 20, 2010. Retrieved March 31, 2011.

- "Royal Caribbean Announces Allure Of The Seas' Inaugural Season". Royal Caribbean International. 2009. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- "Port Everglades: 300 million for Dredging in 2 billion dollar expansion plan (USA)". Dredging Today. March 3, 2010. Retrieved April 6, 2011.

- Jeanette Sheppard, Hank Tester (July 15, 2011). "Port of Miami Rail Project Groundbreaking". NBC Miami. Retrieved July 16, 2011.

- "Miami port rail link construction set". Railway Age. July 13, 2011. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved July 16, 2011.

- "Back to the Future: Port of Miami & Florida East Coast Railway?". MiamiDade.gov. 2010. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- Blake, Scott (May 7, 2014). "Seaport rail to expand again". MiamiToday News. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- Zachary S. Fagenson (March 10, 2011). "Million-square-foot Flagler logistics hub key piece of Miami's international trade puzzle". Miami Today News. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- "Port of Miami rail connection breaks ground". WSVN-TV. July 15, 2011. Retrieved July 16, 2011.

- Ashley D. Torres (July 15, 2011). "FEC rail project starts – 800 jobs expected". South Florida Business Journal. Retrieved July 17, 2011.

- "TIGER II Grant". Miami-Dade.gov. 2010. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- Zachary Fagenson (June 2, 2011). "Florida East Coast Rail line to haul 5% of cargo trucks from Port of Miami". Miami Today. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- Hank Tester (June 11, 2010). "FDT Deems Port Tunnel "Really Sexy"". NBC Miami. Retrieved April 1, 2011.

- Yudislaidy Fernandez (July 24, 2008). "Walmart in downtown Miami? Company confirms discussions have taken place, but says no agreements have been made". Miami Today News. Retrieved April 7, 2011.

- Jacquelyn Weiner (June 2, 2011). "Miami to ease financial pressures by refinancing some loans". Miami Today. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- Elaine Walker (July 31, 2011). "Genting Group is betting on Miami as future resort destination". Miami Herald. Retrieved August 1, 2011.

- Muiz, Andria C. (October 1, 2014). "Port Miami Tunnel marks first month of operation". Miami's Community Newspapers. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- Uncredited (November 26, 2010). "Port of Miami seeks funds for 'Deep Dredge' project". SandandGravel.com. Retrieved April 1, 2011.

- Alfonso Chardy (August 21, 2010). "Port of Miami puts rail project on fast track". Miami Herald. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- Zachary Fagenson (June 9, 2011). "Major logistics centers vital to leverage growth at Port of Miami, Miami International Airport". Miami Today. Retrieved June 8, 2011.

- "Construction schedule". Florida Department of Transportation. 2010. Retrieved March 31, 2011.

- Brian Hamacher (May 24, 2010). "Dig This: Port of Miami Tunnel Construction Begins". NBC Miami. Retrieved April 4, 2011.

- "Combi Dock I (IMO: 9400473)". vesseltracker. Retrieved June 24, 2011.

- Alfonso Chardy (June 23, 2011). "Machine to drill Port of Miami tunnel arrives". Miami Herald. Retrieved June 24, 2011.

- Lidia Dinkova, Alfonso Chardy (June 23, 2011). "Ship carrying tunnel boring machine to dock at Port of Miami". Miami Herald. Retrieved June 23, 2011.

- "Boring equipment brought for port tunnel construction". WSVN-TV. June 23, 2011. Retrieved June 23, 2011.

- Alfonso Chardy (May 17, 2011). "Drivers hit the brakes for road construction in S. Fla". Miami Herald. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- Lidia Dinkova (June 27, 2011). "Assembly of tunnel boring machine to cause MacArthur Causeway lane closures". Miami Herald. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- Alfonso Chardy (June 20, 2011). "A giant step for Port of Miami tunnel construction". Miami Herald. Archived from the original on October 8, 2011. Retrieved June 22, 2011.

- Alfonso Chardy, The Miami Herald (August 9, 2011). "Miami tunnel boring machine gets a name: Harriet". Sun Sentinel. Retrieved August 11, 2011.

- Shani Wallis (2010). "Port of Miami Tunnel gets underway". TunnelTalk. Retrieved March 31, 2011.

- Viglucci, Andre (November 14, 2011). "Port of Miami tunnel drilling starts". The Miami Herald. Miami, Florida. Retrieved November 29, 2011.

- "Port of Miami Tunnel Halfway Done".

- "PortMiami tunnel digging reaches end of the line".

- POMT Public Affairs Program Office (June 2, 2010). "Technical Fact Sheet" (PDF). Florida Department of Transportation. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 29, 2011. Retrieved July 17, 2011.

- Janie Campbell (March 12, 2011). "Rogue Contractor Dumps Tunnel Fill In Wetlands". NBC Miami. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- Miami Herald Editorial (June 25, 2011). "Don't make Virginia Key a casualty". Miami Herald. Retrieved June 25, 2011.

- Andres Viglucci (March 11, 2011). "Tunnel contractor makes wetland mess". Miami Herald. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- "USA: Officials Propose Virginia Key Park's North Point for Dumping Site". Dredging Today. June 28, 2011. Retrieved June 29, 2011.

- Jacquelyn Weiner (June 16, 2011). "Downtown Miami inlet a dredging dump site?". Miami Today News. Retrieved June 25, 2011.

- Erik Bojnansky (August 4, 2011). "A Waterfront Park for All to Enjoy". Biscayne Times. Retrieved August 4, 2011.

- Michael Miller (March 23, 2011). "Does Bouygues, Contractor On The $1 Billion Port Of Miami Tunnel, Have A $1 Million Yacht?". Miami New Times. Retrieved April 7, 2011.

- Alfonso Chardy (July 31, 2011). "Tunnel builder accused of trespassing on seaplane base". Miami Herald. Retrieved August 1, 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Port of Miami Tunnel. |