Political culture

Political culture describes how culture impacts politics. Every political system is embedded in a particular political culture.[1] Its origins as a concept go back at least to Alexis de Tocqueville, but its current use in political science generally follows that of Gabriel Almond.[1]

Definition

María Eugenia Vázquez Semadeni defines political culture as "the set of discourses and symbolic practices by means of which both individuals and groups articulate their relationship to power, elaborate their political demands and put them at stake."[2]

Gabriel Almond defines it as "the particular pattern of orientations toward political actions in which every political system is embedded".[1]

Lucian Pye's definition is that "Political culture is the set of attitudes, beliefs, and sentiments, which give order and meaning to a political process and which provide the underlying assumptions and rules that govern behavior in the political system".[1]

Analysis

The limits of a particular political culture are based on subjective identity.[1] The most common form of such identity today is the national identity, and hence nation states set the typical limits of political cultures.[1] The socio-cultural system, in turn, gives meaning to a political culture through shared symbols and rituals (such as a national independence day) which reflect common values.[1] This may develop into a civil religion. The values themselves can be more hierarchical or egalitarian, and will set the limits to political participation, thereby creating a basis for legitimacy.[1] They are transmitted through socialization, and shaped by shared historical experiences which form the collective or national memory.[1] Intellectuals will continue to interpret the political culture through political discourse in the public sphere.[1] Indeed, elite political culture is more consequential than mass-level.[3]

Elements

Trust is a major factor in political culture, as its level determines the capacity of the state to function.[3]

Postmaterialism is the degree to which a political culture is concerned with issues which are not of immediate physical or material concern, such as human rights and environmentalism.[1]

Classifications

Different typologies of political culture have been proposed.

Almond & Verba

Gabriel Almond and Sidney Verba in The Civic Culture outlined three pure types of political culture based on level and type of political participation and the nature of people's attitudes toward politics:

- Parochial – Where citizens are only remotely aware of the presence of central government, and live their lives near enough regardless of the decisions taken by the state, distant and unaware of political phenomena. They have neither knowledge nor interest in politics. This type of political culture is in general congruent with a traditional political structure.

- Subject – Where citizens are aware of central government, and are heavily subjected to its decisions with little scope for dissent. The individual is aware of politics, its actors and institutions. It is affectively oriented towards politics, yet it is on the "downward flow" side of the politics. In general congruent with a centralized authoritarian structure.

- Participant – Citizens are able to influence the government in various ways and they are affected by it. The individual is oriented toward the system as a whole, to both the political and administrative structures and processes (to both the input and output aspects). In general congruent with a democratic political structure.

Almond and Verba wrote that these types of political culture can combine to create the civic culture, which mixes the best elements of each.

Elazar

Daniel J. Elazar identified three kinds of political culture:[3]

- Individualistic culture – In which politics is a marketplace between individuals seeking to maximize their self-interest, with minimal community involvement and opposition to the government, as well as a high degree of patronage. See also: Neopatrimonialism.

- Moralistic culture – Whereby government is seen as important and as a way to improve peoples' lives.

- Traditionalistic culture – One which seeks to preserve the status quo under which elites have all the power and citizen participation is not expected.

Huntington

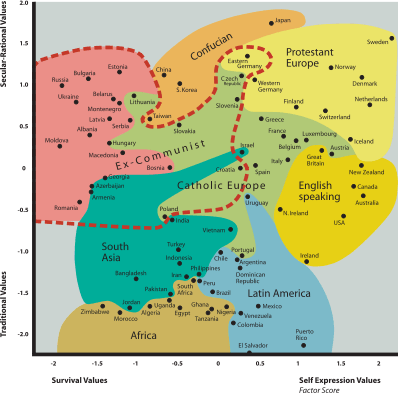

Samuel P. Huntington classified political cultures according to civilizations on the basis of geography and history:[3]

National political cultures

Russia

Russia is a low-trust society, with even the highest trusted institutions of church and the military having more distrustful than trusting citizens, and with low participation in civil society.[3][4] This means that Russia has a weak civic political culture. Furthermore, the authoritarian traditions of Russia mean that there is little support for democratic norms such as tolerance of dissent and pluralism.[5] Russia has a history of authoritarian rulers from Ivan the Terrible to Joseph Stalin, who have engaged in massive repression of all potential political competitors, from the oprichnina to the Great Purge. The resulting political systems of Tsarist autocracy and Soviet communism had no space for independent institutions.

United States

The political culture of the United States was heavily influenced by the background of its early immigrants, as it is a settler society. Samuel P. Huntington identified American politics as having a "Tudor" character, with elements of English political culture of that period, such as common law, strong courts, local self-rule, decentralized sovereignty across institutions, and reliance on popular militias instead of a standing army, having been imported by early settlers.[6] Another source of political culture was the arrival of Scotch-Irish Americans, who came from a violent region of Britain, and brought with them a strong sense of individualism and support for the right to bear arms.[7] These settlers provided the support for Jacksonian democracy, which was a revolution of its time against the established elites, and remnants of which can still be seen in modern American populism.[7]

See also

References

- Morlino, Leonardo (2017). Political science : a global perspective. Berg-Schlosser, Dirk., Badie, Bertrand. London, England. pp. 64–74. ISBN 978-1-5264-1303-1. OCLC 1124515503.

- [Vázquez Semadeni, M. E. (2010). La formación de una cultura política republicana: El debate público sobre la masonería. México, 1821-1830. Serie Historia Moderna y Contemporánea/Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas; núm. 54. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México/El Colegio de Michoacán. ISBN 978-607-02-1694-7]

- Hague, Rod. (14 October 2017). Political science : a comparative introduction. pp. 200–214. ISBN 978-1-137-60123-0. OCLC 970345358.

- Schmidt-Pfister, Diana (2008), White, Stephen (ed.), Media, Culture and Society in Putin’s Russia, Studies in Central and Eastern Europe, Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 37–71, doi:10.1057/9780230583078_3, ISBN 978-0-230-58307-8 Missing or empty

|title=(help);|chapter=ignored (help) - White, Stephen, 1945- Gitelman, Zvi Y. Sakwa, Richard. (2005). Developments in Russian politics 6. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-3668-4. OCLC 57638942.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Huntington, Samuel P. (2006). Political order in changing societies. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11620-5. OCLC 301491120.

- Fukuyama, Francis. (30 September 2014). Political order and political decay : from the industrial revolution to the globalization of democracy. Continuation of: Fukuyama, Francis. (First ed.). New York. ISBN 978-0-374-22735-7. OCLC 869263734.

Further reading

- Almond, Gabriel A., Verba, Sidney The Civic Culture. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company, 1965.

- Aronoff, Myron J. “Political Culture,” in International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences, Neil J. Smelser and Paul B. Baltes, eds., (Oxford: Elsevier, 2002), 11640.

- Axelrod, Robert. 1997. “The Dissemination of Culture: A Model with Local Convergence and Global Polarization.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 41:203-26.

- Barzilai, Gad. Communities and Law: Politics and Cultures of Legal Identities. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2003.

- Bednar, Jenna and Scott Page. 2007. “Can Game(s) Theory Explain Culture? The Emergence of Cultural Behavior within Multiple Games” Rationality and Society 19(1):65-97.

- Clark, William, Matt Golder, and Sona Golder. 2009. Principles of Comparative Government. CQ Press. Ch. 7

- Diamond, Larry (ed.) Political Culture and Democracy in Developing Countries.

- Greif, Avner. 1994. “Cultural Beliefs and the Organization of Society: A Historical and Theoretical Reflection on Collectivist and Individualist Societies.” The Journal of Political Economy 102(5): 912-950.

- Kertzer, David I. Politics and Symbols. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1996.

- Kertzer, David I. Ritual, Politics, and Power. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1988.

- Kubik, Jan. The Power of Symbols Against The Symbols of Power. University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1994.

- Inglehart, Ronald and Christian Welzel, Modernization, Cultural Change and Democracy. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005. Ch. 2

- Laitin, David D. Hegemony and Culture. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 1986.

- Igor Lukšič, Politična kultura. Ljubljana: The University of Ljubljana, 2006.

- Wilson, Richard "The Many Voices of Political Culture: Assessing Different Approaches," in World Politics 52 (January 2000), 246-73

- Gielen, Pascal (ed.), 'No Culture, No Europe. On the Foundation of Politics'. Valiz: Amsterdam, 2015.